George Henry Durrie stands as a distinctive figure in nineteenth-century American art. While perhaps not possessing the widespread contemporary fame of the leading Hudson River School painters during his lifetime, his intimate and evocative depictions of rural New England life, particularly its snow-covered landscapes, have secured him a lasting place in the American cultural consciousness. His work, amplified through popular lithographs, came to define a nostalgic vision of the American past, one characterized by quiet resilience, community, and the stark beauty of the winter season. Born in 1820 and passing away prematurely in 1863, Durrie captured a specific time and place with a sincerity and charm that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

George Henry Durrie was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on June 6, 1820. His roots were firmly planted in New England, a region that would become the primary subject of his artistic endeavors. His father, John Durrie, was a notable figure in Hartford, having co-founded Durrie & Peck, a company involved in publishing, bookselling, and stationery. This background likely provided the young Durrie with a degree of stability and perhaps exposure to the visual arts through printed materials, although his path would lead him towards creating images rather than selling them.

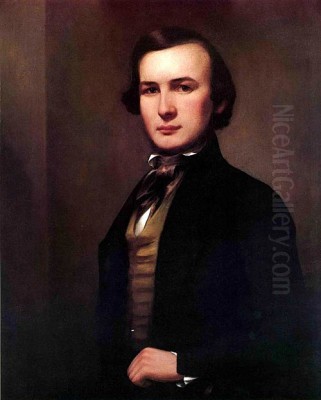

The crucial step in his artistic formation came in 1839. At the age of nineteen, Durrie moved to New Haven, Connecticut – the city that would become his lifelong home – to begin formal art training. He apprenticed under Nathaniel Jocelyn, a respected and successful portrait painter in the region. Jocelyn, along with his partner Samuel S. B. Morse (who later gained greater fame for the telegraph), ran a prominent studio. Training with Jocelyn provided Durrie with a solid foundation in drawing, composition, and the techniques of oil painting, initially focused, as was common for aspiring artists of the time, on the lucrative field of portraiture.

The Itinerant Portraitist

Following his initial training with Nathaniel Jocelyn, Durrie embarked on a period common for many American artists of his generation: he became an itinerant painter. For several years, roughly between 1839 and 1842, he traveled through various parts of the country seeking commissions, primarily for portraits. His journeys took him through different areas of Connecticut and Massachusetts, and further afield to New Jersey and Virginia. This experience, while focused on capturing likenesses, undoubtedly exposed him to a wider variety of landscapes and communities than he had known in Hartford and New Haven.

Working as an itinerant artist required adaptability and the ability to connect with diverse clientele. It was a practical way to earn a living while honing one's craft. While portraiture remained a part of his output throughout his career, these early travels likely deepened his appreciation for the character of the American countryside and the lives of its inhabitants. This period of moving from town to town, observing different settings and seasons, may have subtly planted the seeds for his later shift towards landscape and genre scenes, offering him firsthand material for the rural settings he would eventually become famous for depicting. In 1841, during this phase, he married Sarah Perkins, establishing a family life that would anchor him more firmly in New Haven upon his return.

A Shift Towards Landscape and Winter

By the mid-1840s, a noticeable shift began to occur in Durrie's artistic focus. While he continued to accept portrait commissions, his interest increasingly turned towards landscape painting. Initially, he painted views of the local New Haven scenery, including well-known landmarks like East Rock and West Rock. These early landscapes show his developing skill in capturing natural forms and atmospheric effects. However, it was his decision to specialize in winter scenes that truly set him apart and defined his artistic identity.

Durrie recognized the unique appeal and visual possibilities of snow. Around 1845, he began to incorporate snow into his landscapes, finding that these "snow pieces," as they were sometimes called, proved particularly popular. In the context of American art at the time, where the lush greens of summer or the fiery hues of autumn often dominated landscape painting – exemplified by artists like Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand of the Hudson River School – Durrie's consistent focus on winter was relatively novel. He embraced the challenges of depicting snow's textures, its interaction with light, and the specific mood it cast upon the familiar New England countryside.

His winter scenes were not merely topographical records; they were imbued with a sense of narrative and human presence. Farmhouses nestled under blankets of snow, sleighs gliding along country roads, figures engaged in daily chores like chopping wood or gathering ice – these became recurring motifs. Durrie wasn't painting the wilderness sublime favored by some contemporaries like Albert Bierstadt, but rather the domesticated, working landscape, finding beauty and quiet dignity in the everyday routines of rural life during its harshest season. This focus on the specific character and activities of New England winters became his signature.

Artistic Style and Technique

George Henry Durrie developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by clarity, meticulous detail, and a somewhat crisp, linear quality. While influenced by the prevailing realism of the mid-nineteenth century, his work often possesses a charm that borders on the naive or folk tradition, yet it is underpinned by careful observation and competent technique learned from his training with Nathaniel Jocelyn. He was less concerned with the grand, panoramic vistas favored by Frederic Edwin Church or the overtly spiritual allegories sometimes present in the work of Thomas Cole. Instead, Durrie focused on more intimate, eye-level views of the rural world he knew.

His paintings are notable for their bright, clear light and often vibrant color palettes, even within winter scenes where blues, whites, and cool grays dominate, often punctuated by the warm reds of barns or the dark greens of pine trees. He paid close attention to specific details: the texture of weathered wood on a barn, the intricate patterns of bare tree branches against the sky, the specific way snow drifts against a fence or clings to a roof. This detailed approach lends his work an air of authenticity and groundedness. Figures in his paintings, while often small in scale compared to the landscape, are integral, suggesting the human presence within nature and depicting activities central to rural life.

Compositionally, Durrie often employed recurring elements. A road or path frequently leads the viewer's eye diagonally into the scene, past a prominent farmhouse or cluster of buildings, towards distant, rolling hills under a wide sky. While not strictly adhering to the atmospheric concerns of Luminist painters like John F. Kensett or Sanford Robinson Gifford, Durrie's skies and rendering of light, particularly the cool, clear light of winter, contribute significantly to the mood of his paintings. His style was less about painterly flourish and more about careful delineation and the creation of a coherent, believable, and often idyllic scene.

Iconic Themes: The New England Winter

Winter was undeniably George Henry Durrie's most celebrated and recurring theme. He returned again and again to the subject, exploring various facets of New England rural life during the coldest months. His paintings captured not just the visual appearance of snow and ice, but also the atmosphere and activities associated with the season. He seemed fascinated by the way snow transformed the familiar landscape, simplifying forms, creating stark contrasts, and imposing a sense of quiet stillness.

His winter scenes often depict snug farmsteads, symbols of warmth and shelter against the cold. Smoke curling from chimneys suggests hearth and home. Figures are shown engaged in necessary winter tasks: farmers driving ox-drawn sleds laden with wood, men cutting blocks of ice from frozen ponds (a vital activity before refrigeration), families traveling by sleigh perhaps returning home or visiting neighbors. These activities ground the picturesque scenes in the realities of nineteenth-century rural existence. Works like Gathering Wood for Winter or Ice Gathering highlight the labor involved in surviving and thriving through the season.

Beyond the documentary aspect, Durrie's winter landscapes evoke a powerful sense of nostalgia and idealized community. In an era of increasing industrialization and urbanization, his paintings offered viewers, particularly those in cities, a comforting vision of a simpler, agrarian past or present. The scenes often possess a peaceful, almost serene quality, emphasizing harmony between humanity and nature, even in the face of winter's challenges. This nostalgic appeal, depicting resilience, neighborliness, and the enduring rhythms of country life, was a key factor in their popularity, both as original paintings and as affordable prints.

Key Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of George Henry Durrie's style and thematic concerns. Among the most famous, largely due to its widespread reproduction by Currier & Ives, is Home to Thanksgiving. Painted around 1861, this work encapsulates the nostalgic ideal of family and rural homecoming. It depicts a prosperous farmstead in late autumn or early winter, with various figures arriving by carriage and on foot, converging on the welcoming house, smoke rising invitingly from its chimney. The scene radiates warmth, abundance, and familial connection, becoming an enduring image of the American Thanksgiving holiday.

His numerous winter landscapes often share titles like Winter Scene, Winter in the Country, or Farmyard in Winter, indicating variations on his core theme. A typical example might feature a red farmhouse and outbuildings partially covered in snow, set against a backdrop of bare trees and distant hills under a clear winter sky. Often, a sleigh drawn by horses travels along a foreground road, adding a dynamic element and human interest. Winter in the Country: A Cold Morning (1861), for instance, vividly portrays the crisp atmosphere and activities of a farm at the start of a winter day.

Other works highlight specific rural activities. Cider Making (c. 1857-1863) depicts a communal autumn activity, showcasing the process outside a barn, emphasizing community and the fruits of the harvest before winter sets in. Wood for Winter (1860) focuses on the essential task of logging and transporting firewood, often showing oxen pulling heavy sleds through the snow. Seven Miles to Farmington (1853) captures the feeling of travel and distance in the winter landscape. These works, whether depicting the depths of winter or the preparations for it, consistently reflect Durrie's intimate knowledge and affectionate portrayal of nineteenth-century New England life.

Durrie and His Contemporaries

George Henry Durrie worked during a vibrant period in American art, largely dominated by the Hudson River School and the rise of genre painting. While sharing the Hudson River School's interest in the American landscape, Durrie's approach differed significantly from its leading figures. He rarely aimed for the sublime grandeur found in the monumental canvases of Albert Bierstadt's Western scenes or the dramatic, often allegorical, landscapes of Thomas Cole. His focus remained steadfastly on the familiar, domesticated scenery of New England.

Compared to Asher B. Durand, who succeeded Cole as a leader of the Hudson River School and emphasized detailed, naturalistic renderings of the Catskills and Adirondacks, Durrie's work appears simpler in composition and perhaps less overtly concerned with capturing the wildness of nature. Jasper Francis Cropsey, another contemporary, became renowned for his brilliant depictions of autumn foliage, offering a seasonal counterpoint to Durrie's winter specialization. While Durrie's handling of light could be sensitive, it generally lacked the pervasive, atmospheric haze and focus on light itself that characterized the Luminist painters like John F. Kensett, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Fitz Henry Lane.

Durrie's work perhaps aligns more closely with the era's genre painters, artists who focused on scenes of everyday life. William Sidney Mount on Long Island and George Caleb Bingham in Missouri captured the activities and character of their respective regions. Eastman Johnson, known as the "American Rembrandt," depicted both rural scenes (like his maple sugaring images from Maine) and domestic interiors with keen observation. While Durrie's figures are often secondary to the landscape setting, his emphasis on activities like cider making, ice harvesting, and farm chores places his work firmly within the spirit of genre painting, documenting the customs and labor of ordinary people. He exhibited his work alongside many of these artists at venues like the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

The Currier & Ives Connection

A crucial factor in the enduring fame of George Henry Durrie, particularly after his death, was the popularization of his work through the New York printing firm of Currier & Ives. Founded by Nathaniel Currier, who was later joined by James Merritt Ives, the firm billed itself as "Publishers of Cheap and Popular Pictures." They specialized in producing affordable lithographic prints on a vast array of subjects, including news events, portraits, historical scenes, and, significantly, idealized depictions of American life.

Currier & Ives recognized the appeal of Durrie's charming and nostalgic New England scenes. Starting in the early 1860s, shortly before and after Durrie's death, the firm acquired rights to reproduce several of his paintings as hand-colored lithographs. Ten of his compositions were eventually issued as large folio prints, becoming some of the most popular and iconic images the company ever produced. Titles like Home to Thanksgiving, Winter in the Country: A Cold Morning, and The Old Homestead in Winter reached a vast audience across the United States, far larger than could ever see Durrie's original oil paintings.

The lithographs were not always exact copies. Sometimes compositions were slightly altered, simplified, or adapted by the firm's staff artists to suit the printing process or enhance popular appeal. Nevertheless, these prints effectively disseminated Durrie's vision of a cozy, resilient, and picturesque rural America. They decorated the walls of countless homes, shaping the popular imagination and cementing Durrie's association with the quintessential New England winter landscape. This partnership, though perhaps more impactful posthumously, ensured that Durrie's art became deeply embedded in American visual culture.

Later Life and Premature Death

George Henry Durrie spent the majority of his adult life and career based in New Haven, Connecticut. He remained active as a painter, continuing to produce his characteristic landscapes and occasional portraits. While New Haven was his home base, records indicate he maintained a studio space in New York City for a brief period, likely to be closer to exhibition venues like the National Academy of Design and potential patrons or dealers, including Currier & Ives. He participated in the artistic life of his community and region, exhibiting his works regularly.

Despite the growing popularity of his scenes, particularly as prints began to circulate, Durrie did not achieve the level of critical acclaim or financial success enjoyed by the era's most celebrated artists during his lifetime. His focus on familiar, local scenes and his somewhat straightforward style may have been perceived as less ambitious than the grander subjects tackled by some of his contemporaries.

Tragically, George Henry Durrie's life and career were cut short. He died suddenly in New Haven on October 15, 1863, at the relatively young age of 43. The exact cause of his death is not always clearly stated in historical records, but its prematurity meant that he would not witness the full extent of his posthumous fame, largely driven by the continued popularity of the Currier & Ives prints based on his paintings. He left behind his wife, Sarah, and several children, as well as a significant body of work capturing the essence of his beloved New England.

Legacy and Rediscovery

During his lifetime, George Henry Durrie was a respected regional artist, but his national reputation was modest compared to the giants of the Hudson River School. His most significant legacy during the decades immediately following his death was sustained primarily through the widespread distribution of Currier & Ives lithographs. These prints kept his imagery – particularly the cozy winter farmsteads and scenes of rural activity – alive in the public consciousness, making his vision synonymous with a certain idealized version of nineteenth-century American life.

A critical reappraisal and rediscovery of Durrie's original paintings began in the early twentieth century, particularly during the 1920s and 1930s. This coincided with a growing interest in American folk art and a wave of nostalgia for the nation's pre-industrial past, often termed "Colonial Revival," although Durrie's work depicted his own time. Collectors and curators began to recognize the unique charm, sincerity, and skilled observation in his oil paintings, distinguishing them from the mass-produced prints. His work was increasingly sought after, and exhibitions dedicated to his art helped solidify his reputation.

Today, George Henry Durrie is recognized as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American genre and landscape painting. His works are held in major museum collections, including the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Wadsworth Atheneum (in his native Hartford), and the White House Collection. He is valued for his authentic portrayal of New England rural life, his pioneering focus on winter landscapes, and his ability to evoke a sense of place and time with clarity and affection. His paintings, once overshadowed by prints, are now appreciated for their artistic merit and their contribution to the visual narrative of America.

Conclusion

George Henry Durrie carved a unique niche for himself within the bustling art world of mid-nineteenth-century America. Turning from the common path of portraiture, he dedicated himself to capturing the landscapes and life of his native New England, finding particular inspiration in the transformative beauty and quiet resilience of winter. His detailed, brightly lit, and compositionally clear paintings offered an intimate and often nostalgic counterpoint to the grander visions of some contemporaries. While his teacher Nathaniel Jocelyn grounded him in technique, and artists like William Sidney Mount shared his interest in genre, Durrie's consistent focus on the snow-covered countryside set him apart.

Though his contemporary fame was moderate, his partnership with Currier & Ives ensured his imagery reached an unparalleled audience, making his depictions of farmsteads, sleigh rides, and winter chores iconic representations of American rural life. The posthumous rediscovery of his original paintings revealed the sensitivity and skill underlying the popular prints. Today, George Henry Durrie is appreciated not just as the "snowman" of American painting, but as a keen observer and sincere chronicler of a specific time and place, whose work continues to evoke the enduring appeal of the New England landscape and the quiet rhythms of its past.