Ammi Phillips stands as one of the most significant and prolific folk portrait painters in the history of American art. Active for over five decades during the first half of the 19th century, Phillips created a vast body of work that captured the likenesses of the rural inhabitants of western Connecticut, Massachusetts, and the neighboring Hudson River Valley region of New York. Born in Colebrook, Connecticut, on April 24, 1788, and passing away in Curtisville (now Interlaken), Massachusetts, on July 11, 1865, his life spanned a transformative period in American history. Despite his immense output, estimated at potentially over eight hundred portraits, Phillips remained largely anonymous for nearly a century after his death, his works often attributed to unknown artists dubbed the "Border Limner" and the "Kent Limner." The eventual unraveling of this mystery revealed a singular, adaptable, and remarkably enduring artistic talent.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Ammi Phillips was born into a reasonably established New England family, the son of Samuel Phillips and Millea Phillips (née Johnson). Colebrook, his birthplace, was a small, relatively rural town in Litchfield County, Connecticut. There is no record of Phillips receiving any formal artistic training. Like many folk artists of his era, he appears to have been largely self-taught, likely honing his skills through observation, practice, and perhaps by studying available prints or the work of other local artisans. The term "limner," often used historically to describe portrait painters, particularly those who were itinerant or worked outside academic traditions, aptly fits Phillips's early career.

He began his professional life as a painter around 1809, embarking on a career that would see him travel extensively through the countryside, seeking commissions from the growing middle class of farmers, merchants, doctors, ministers, and their families. This itinerant lifestyle was common for artists outside major urban centers, where established patronage networks were scarce. Phillips needed to go where the clients were, often staying with families while he completed their portraits. His early advertisements, though few have survived, indicate his intention to capture a "correct likeness."

His first marriage was to Laura Brockway in Colebrook around 1813. They had several children before Laura's death sometime before 1830. Phillips later married Jane Ann Caulkins, and they also had children together. His family life often intertwined with his travels, with the family relocating several times within his working territory, moving between Connecticut and New York over the decades. These moves likely reflected his shifting centers of operation as he sought new clientele.

The Life of an Itinerant Painter

For over fifty years, Ammi Phillips traversed the landscapes of western New England and eastern New York. His primary working territory encompassed the Litchfield Hills of Connecticut, Berkshire County in Massachusetts, and Dutchess and Columbia counties in New York, along the vital corridor of the Hudson River Valley. This region was characterized by agricultural communities and small but growing towns populated by individuals eager to document their status and family ties through portraiture, especially in an era before the widespread availability of photography.

The life of an itinerant painter demanded resilience, adaptability, and business acumen. Phillips would travel by horse, wagon, or perhaps sometimes by boat along the Hudson, carrying his canvases, pigments, oils, and brushes. He likely relied on word-of-mouth recommendations, connections through community networks (perhaps church or Masonic affiliations), and possibly occasional newspaper advertisements to secure commissions. The process often involved staying in the homes of his sitters for days or weeks while he completed the portraits of various family members.

This mode of working influenced his style. He needed to work relatively quickly and efficiently to make a living. His materials were often locally sourced or what he could easily transport. The demands of his clientele – primarily a desire for a recognizable likeness and a depiction of respectable status through clothing and posture – shaped the focus of his work. He was not painting for the sophisticated art critics of Boston or New York City, but for his neighbors and community members in the rural towns and villages.

Artistic Development and Stylistic Periods

One of the most fascinating aspects of Ammi Phillips's career is the distinct evolution of his artistic style over five decades. Art historians, particularly Barbara and Lawrence Holdridge whose research was pivotal in identifying Phillips, have categorized his work into several periods, most notably the "Border Limner" phase and the "Kent Limner" phase, reflecting stylistic shifts and geographic centers of activity.

The Early Years: The Border Limner Period

Active roughly between 1812 and 1819, the works associated with the "Border Limner" are characterized by a soft, ethereal quality. Phillips worked primarily along the border region of Connecticut and Massachusetts during this time. Portraits from this period often feature sitters with pale complexions, large, somewhat almond-shaped eyes that gaze directly at the viewer, and delicately rendered features. The color palette is typically light and restrained, dominated by pastel shades, creams, and soft grays. Figures often appear somewhat elongated and weightless against plain, light backgrounds. There's a gentle, almost naive charm to these early works, such as the portrait of Harriet Leavens (c. 1815), showcasing the delicate brushwork and serene expressions typical of this phase.

Transition and Development

The 1820s represent a period of transition in Phillips's work. While retaining some of the softness of the Border period, his paintings began to show increased modeling and a slightly bolder approach to form. He continued to travel and paint widely, adapting his technique perhaps in response to changing tastes or his own developing skills. This decade is less stylistically cohesive than the periods that flank it, but it demonstrates his ongoing experimentation and refinement as he moved towards the more dramatic style that would define his middle career.

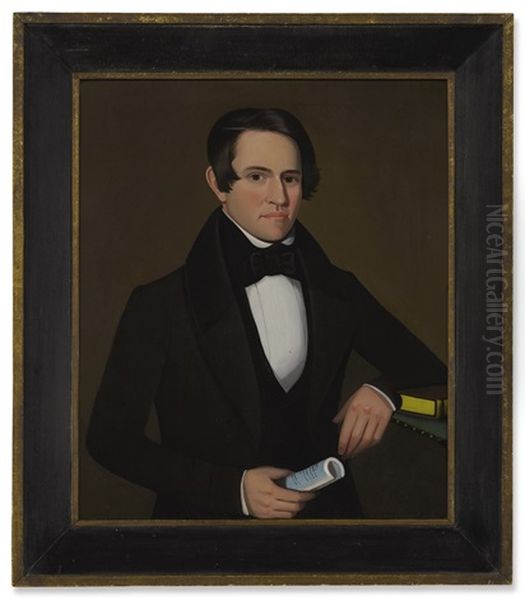

The Kent Limner Period: Boldness and Austerity

Around 1829, Phillips settled for a time near Kent, Connecticut, marking the beginning of what is known as the "Kent Limner" period, lasting until about 1838. This phase represents a dramatic shift towards a bolder, more austere, and highly distinctive style. Backgrounds become dark, often plain black or deep brown, throwing the figures into sharp relief. Colors are stronger and contrasts more pronounced. Stark whites are used for collars and caps, and Phillips frequently employed vibrant reds, particularly for upholstery like sofas or details like books held by the sitters.

Figures in the Kent period appear more solid and three-dimensional, though still retaining a certain folk rigidity and flatness. Poses are often stiffly formal, and faces, while clearly individualized, take on a stern or sober expression. The compositions are powerful and direct. Works like the iconic portraits of Joseph Slade and Alsa Slade (c. 1816, though sometimes debated and placed earlier, their starkness fits the Kent sensibility) or Woman with Pink Ribbons (c. 1830) exemplify the dramatic intensity, strong color contrasts, and compelling presence characteristic of this highly regarded phase. This style proved very popular with his clientele in the Hudson Valley.

Later Styles: Maturity and Adaptation

From the late 1830s through the end of his career in the early 1860s, Phillips's style continued to evolve. The starkness of the Kent period gradually softened. While he maintained his direct approach to likeness, his modeling became more nuanced, suggesting volume and form with greater subtlety. Backgrounds became more varied, sometimes including hints of interiors or landscapes, though still generally simplified. His color palette remained rich but perhaps less reliant on the dramatic contrasts of the Kent years.

Some art historians suggest the influence of the emerging medium of photography (daguerreotypes) might be visible in the tighter compositions and more conventionally "realistic" portrayal in some later works. However, Phillips never lost his distinctive folk sensibility. His figures always retain a certain stylization, a directness, and an emphasis on pattern and decorative detail, particularly in clothing. Portraits from this era, such as those of the Ten Broeck family or Dr. Russell Dorr and his son, show a mature artist confidently rendering his subjects, adapting his long-honed skills to the prevailing tastes while retaining his unique artistic signature.

Hallmarks of Phillips's Art

Across his various stylistic periods, several consistent characteristics define Ammi Phillips's work. His portraits are almost always marked by a direct, penetrating gaze from the sitter, creating an immediate connection with the viewer. He had a remarkable ability to capture a specific likeness, a feature often commented upon by his contemporaries and crucial to his success as a portraitist.

Compositionally, his works often feature figures, particularly women and children, seated in chairs or sofas, frequently holding symbolic objects like books, flowers, or letters. Clothing is rendered with careful attention to detail, pattern, and texture, serving not only as decoration but also as an indicator of the sitter's social standing. Lace collars, intricate bonnets, colorful vests, and patterned fabrics are meticulously depicted, often contrasting with the simplified treatment of anatomy or background.

Phillips employed a limited but effective color palette, often relying on strong contrasts, especially during his Kent period. His use of specific colors, like the recurring vibrant reds or the stark blacks and whites, became signature elements. While perspective and anatomical accuracy often adhere to folk conventions (meaning they can appear flattened or slightly disproportionate by academic standards), this simplification contributes to the graphic power and abstract quality of his best work. He achieved a unique blend of realism in capturing likeness and abstraction in his overall design.

Iconic Works

While Phillips produced hundreds of portraits, several have become particularly well-known and are considered icons of American folk art.

Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog

Perhaps Phillips's most famous painting is Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog (c. 1830-1835). Housed in the American Folk Art Museum in New York City, this portrait embodies the charm and bold design of his Kent Limner period. The anonymous young girl, dressed in a striking coral-red dress, stands against a dark, ambiguous background. Her direct gaze, the slightly awkward yet endearing pose, the detailed rendering of her white pantalettes and black shoes, and the inclusion of her two pets create a memorable and compelling image. The painting's vibrant color, strong composition, and the subject's enigmatic expression have made it a perennial favorite.

The Slade Portraits

The portraits of Joseph Slade and Alsa Slade (often dated c. 1816, but stylistically resonant with the later Kent period's austerity) are powerful examples of Phillips's ability to convey character. Joseph Slade, a farmer and businessman, is depicted with a stern, determined expression, his features sharply defined against a dark background. Alsa Slade, his wife, is shown with similar sobriety, her face framed by a white cap, her dark dress providing a stark contrast. Together, they represent the hardworking, respectable citizens of the communities Phillips served. Their unadorned directness is characteristic of his approach.

Other Notable Portraits

Numerous other works highlight Phillips's skill and range. Harriet Leavens (c. 1815) is a prime example of his early Border Limner style, with its delicate features and pale palette. Woman with Pink Ribbons (c. 1830) showcases the Kent style's bold contrasts and decorative details. Portraits of children were a significant part of his output, often capturing a sense of solemnity mixed with youthful presence. Family groups, though less common, also appear in his oeuvre. Each portrait offers a glimpse into the life of an individual and the society of early 19th-century rural America.

The Unraveling of a Mystery

For decades after Ammi Phillips's death in 1865, his artistic identity faded into obscurity. While his paintings were collected and admired, particularly during the folk art revival of the early 20th century, they were attributed to anonymous hands. Art historians, lacking signed works or documentation, grouped stylistically similar portraits under convenient labels. The delicate, pale works from the Connecticut-Massachusetts border area were assigned to the "Border Limner," while the later, bolder, dark-background portraits from the Hudson Valley were attributed to the "Kent Limner." It was generally assumed these were two or possibly more different artists.

The breakthrough came in the late 1950s. In 1958, collectors Barbara and Lawrence Holdridge acquired a portrait, George C. Sunderland, which was signed "Ammi Phillips Pinxt / 1840" on the reverse. This crucial piece of evidence spurred the Holdridges, along with fellow researcher Mary Black, on a decade-long quest. They meticulously compared the signed work with hundreds of unattributed portraits, analyzing stylistic traits – the way eyes were painted, the handling of fabric, compositional patterns, characteristic color choices. They also delved into genealogical records, census data, local histories, and account books from the regions where Phillips was known to have lived and worked.

Their painstaking research conclusively demonstrated that the works of the "Border Limner" and the "Kent Limner," despite their stylistic differences, were in fact created by the same artist: Ammi Phillips. They revealed that these were not different painters, but different phases in the long and evolving career of a single, highly adaptable artist. The Holdridges published their initial findings in 1959 and presented a landmark exhibition, "Ammi Phillips: Portrait Painter 1788-1865," at the Connecticut Historical Society in 1965, followed by publications that cemented Phillips's identity and established the vast scope of his oeuvre. This rediscovery fundamentally reshaped the understanding of 19th-century American folk art.

Phillips in the Context of American Folk Art

Ammi Phillips worked during a golden age of American folk art. In the decades following the Revolution and before the widespread adoption of photography in the mid-19th century, there was a burgeoning demand for portraits among ordinary Americans. Unlike the academically trained artists like Gilbert Stuart, Thomas Sully, or Rembrandt Peale, who primarily served wealthier urban elites, folk painters like Phillips catered to a broader, more rural clientele.

These artists were often self-taught or minimally trained, developing distinctive, personal styles outside the conventions of European academic art. Their work is frequently characterized by flattened perspective, simplified forms, strong outlines, attention to decorative detail, and a focus on capturing a recognizable likeness rather than idealized beauty or complex psychological depth. Phillips exemplifies many of these traits, yet his skill in composition, color, and capturing personality elevates his work.

He was part of a vibrant network of itinerant and regional artists. His contemporaries included figures like Erastus Salisbury Field, known for his imaginative historical scenes as well as portraits; Rufus Porter, famous for his landscape murals and founding of Scientific American magazine, but also a portraitist; Sheldon Peck, whose bold, decorative portraits share some affinities with Phillips; Zedekiah Belknap, another prolific New England portraitist; Joseph H. Davis, known for his distinctive watercolor profiles; William Matthew Prior and his brother-in-law Sturtevant J. Hamblin, who ran painting factories offering portraits at different price points; and female folk artists like Ruth Henshaw Bascom, who created compelling pastel profiles, and Eunice Pinney, known for her narrative watercolors. Even the renowned inventor Samuel F.B. Morse began his career as a portrait painter before turning to the telegraph. Phillips's extensive output and evolving style make him a central figure within this diverse group, demonstrating both the shared characteristics of folk art and his unique individual talent.

The Faces of Rural America

Ammi Phillips's legacy lies not only in the artistic merit of his paintings but also in the invaluable record they provide of early 19th-century American life. His sitters were the backbone of the young nation's rural society: farmers, merchants, mill owners, doctors, lawyers, ministers, craftsmen, and their wives and children. He painted individuals and families across a spectrum of relative prosperity, from modestly comfortable to reasonably affluent within their communities.

His portraits document the fashions, aspirations, and self-perception of these people. The carefully rendered clothing, the Bibles or account books held in hand, the formal poses – all speak to a desire to be seen as respectable, pious, hardworking, and successful members of society. Phillips captured their likenesses with an honesty and directness that often transcends mere documentation, offering glimpses of individual personality beneath the formal exteriors.

His portraits of children are particularly noteworthy. He depicted them with a seriousness that reflects the era's view of childhood, yet often managed to convey a sense of youthful vulnerability or quiet energy. Whether it's the famous Girl in Red Dress or numerous other portraits of boys and girls, Phillips treated his young sitters with the same focused attention as his adult clients, creating memorable images of childhood in rural America.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Ammi Phillips continued to paint actively into the early 1860s, his career spanning the period from the War of 1812 through the threshold of the Civil War. His final works show him still capable of producing strong, characterful portraits. He died on July 11, 1865, in Curtisville (now Interlaken), near Stockbridge, Massachusetts, within the region where he had painted for so many years. He was buried in Amenia, New York, another town central to his life and career.

Following his death, his name and work largely disappeared from public consciousness until the dedicated research of the Holdridges and others brought him back to light in the mid-20th century. Since then, his reputation has grown steadily. He is now recognized as one of the most important American artists of the 19th century, and certainly the most prolific folk portraitist identified from that era.

His works are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Folk Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Fenimore Art Museum, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, the Connecticut Historical Society, and many others. Exhibitions dedicated to his work continue to draw attention to his unique style and historical significance.

Conclusion

Ammi Phillips's journey from an anonymous "Limner" to a celebrated master of American folk art is a testament to both his enduring talent and the dedicated scholarship that recovered his identity. Over a career spanning more than half a century, he created an unparalleled visual record of the people who inhabited the towns and villages of western New England and eastern New York. His ability to capture compelling likenesses, his bold sense of design and color, and his stylistic evolution mark him as a singularly important figure. Phillips did not just paint faces; he painted the character of a region and an era, leaving behind a legacy that continues to resonate with its directness, honesty, and distinctive artistic vision. His hundreds of portraits remain a vital part of America's cultural heritage.