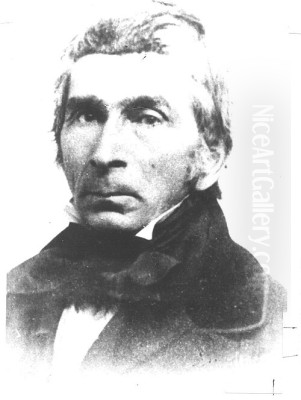

Sheldon Peck stands as a significant, if once overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century American art. Born in an era of national expansion and profound social upheaval, Peck's life and work offer a compelling window into the cultural, artistic, and moral currents of his time. He was not merely a painter of faces; he was a chronicler of a burgeoning American identity, a self-taught artist who developed a distinctive and recognizable style, and a man of deep conviction who risked his safety for the cause of abolition. His journey from the hills of Vermont to the prairies of Illinois is a story of artistic evolution, pioneering spirit, and unwavering commitment to humanitarian ideals.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in New England

Sheldon Peck was born on August 26, 1797, in Cornwall, Addison County, Vermont. This period in New England was characterized by a strong sense of community, religious piety, and a burgeoning spirit of self-reliance. Peck's upbringing in this environment likely shaped his character and, indirectly, his artistic approach. While detailed records of his earliest artistic training are scarce, it is widely accepted that he was largely self-taught. This was not uncommon for artists working outside the established academic centers of the East Coast. Many "limners," as itinerant portrait painters were often called, learned their craft through observation, practice, and perhaps limited instruction from other local artisans.

Peck began his artistic endeavors in his early twenties, focusing on what would become his lifelong specialty: portraiture. In a time before photography became widespread and affordable, painted portraits were the primary means for families, particularly those of some means, to preserve their likenesses for posterity. These early Vermont-period works, dating from roughly the 1820s, exhibit the nascent characteristics of his style: a certain directness, a focus on capturing a likeness rather than flattering the sitter, and a somewhat somber palette. Artists like Winthrop Chandler and Reuben Moulthrop, active in New England in the preceding decades, had laid a groundwork for a regional portraiture style that valued straightforward representation, and Peck's early efforts can be seen within this tradition.

In 1824, Sheldon Peck married Harriet Corey (1806-1887), a union that would last his lifetime and produce ten children. Family life was central to Peck, and his wife Harriet was a steadfast partner, managing the household and contributing to the family's sustenance, particularly in their later years in Illinois.

Migration and Maturation: New York State

Around 1828, seeking new opportunities, Sheldon Peck moved his young family to Jordan, Onondaga County, New York. This region, part of the "Burned-over district" known for its religious revivals and reform movements, may have further influenced Peck's developing social consciousness. Artistically, his New York period (roughly 1828-1836) shows a discernible evolution. His portraits from this time often feature brighter colors and slightly more elaborate compositions.

It was during his New York years that Peck began to incorporate more decorative elements into his portraits, though still maintaining an overall simplicity. He might include a painted frame, a stylized curtain, or a sitter holding a book or flower. These additions, while modest, added visual interest and perhaps appealed to a broader clientele. His figures remained characterized by their serious, often unsmiling expressions, a common trait in early American portraiture reflecting the solemnity of the sitting process and perhaps a Puritan-influenced cultural demeanor. The work of contemporaries like Ammi Phillips, another prolific itinerant painter known for his starkly beautiful portraits in New York and Connecticut, provides a comparative context for Peck's developing style. Phillips, too, adapted his style over his long career, responding to changing tastes and his own artistic growth.

Peck's approach was pragmatic. He was an artisan making a living, traveling to find commissions. His portraits were typically painted on wooden panels, a durable and readily available material. The direct, often intense gaze of his subjects is a hallmark, suggesting an honest and unvarnished encounter between artist and sitter.

The Illinois Years: Art, Activism, and Agriculture

In 1836, the Peck family made another significant move, this time westward to the newly developing state of Illinois. They initially settled in Chicago for about a year before establishing a permanent home in Babcock's Grove, which would later be renamed Lombard, in DuPage County, around 1837. Here, Peck purchased land and built a substantial timber-frame house, which still stands today as the Sheldon Peck Homestead. This move marked a new phase in his life, where farming became a primary means of support, supplemented by his portrait painting.

His Illinois portraits, created from the late 1830s until his death, represent the most mature and recognizable phase of his work. While still rooted in the folk tradition, these paintings often exhibit a greater refinement in technique and a more confident handling of composition. A distinctive feature often noted in his Illinois work is the use of a three-pronged brushstroke, particularly for rendering foliage or decorative tassels, which some scholars and collectors use as an identifying mark, though his works were generally unsigned.

The subjects of his Illinois portraits were often the families of prosperous farmers and local community leaders. Works such as the "Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. David Crane" (c. 1845) or the charming "Children of S. S. Jones and His Wife Junia" (c. 1851) exemplify his Illinois style. The figures are typically presented in a straightforward manner, often half-length or three-quarter length, against plain or minimally decorated backgrounds. Clothing is rendered with attention to its form but without excessive detail, keeping the focus on the sitters' faces. The expressions remain serious and direct, conveying a sense of dignity and character. Other folk artists active in the Midwest during this period, such as Erastus Salisbury Field, who also had New England roots, shared a similar commitment to capturing likeness with a non-academic, direct approach, though Field's work often veered into more imaginative and historical subjects later in his career.

A Staunch Abolitionist and Advocate for Social Justice

Beyond his artistic pursuits, Sheldon Peck was a man of profound moral conviction and a fervent abolitionist. His home in Lombard became a recognized stop on the Underground Railroad, a secret network of routes and safe houses used by enslaved African Americans to escape to freedom in the North and Canada. This was a dangerous undertaking, as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, and particularly the more stringent Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, imposed severe penalties on those who assisted escaped slaves.

Peck's commitment to abolition was unwavering. His son, Frank Peck, later recounted that the family sheltered at least seven freedom seekers in their home. Sheldon Peck was also actively involved in the broader abolitionist movement. He served as a delegate to state and national conventions of the Liberty Party, an early abolitionist political party. He was also reportedly an agent for the abolitionist newspaper, The Western Citizen, published in Chicago. His beliefs extended to other progressive causes of the era, including temperance, pacifism, women's rights, and public education. These deeply held convictions undoubtedly informed his worldview and perhaps even the earnest, unpretentious quality of his portraits, which treat each sitter with a sense of inherent dignity.

His activism places him in the company of other notable figures who combined their professional lives with the fight against slavery. For instance, the renowned painter Eastman Johnson, though working in a more academic style, later in his career created powerful genre scenes depicting African American life, such as "Negro Life at the South" (1859) and "A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves" (c. 1862), which brought the human reality of slavery to a wider audience. While Peck's art did not directly depict abolitionist themes, his life embodied the struggle.

Artistic Style: Simplicity, Directness, and Unflinching Honesty

Sheldon Peck's artistic style is firmly rooted in the American folk art tradition. This tradition, often characterized by artists who were self-taught or received informal training, prioritized directness of expression, strong design, and often a departure from the strict anatomical accuracy and perspectival rules of academic art. Peck's work embodies many of these qualities.

Key Characteristics of Peck's Style:

Simplicity of Composition: Peck typically favored straightforward compositions, often placing his sitters against plain or minimally adorned backgrounds. This lack of clutter directs the viewer's attention squarely to the subject.

Serious Demeanor: The individuals in Peck's portraits almost invariably possess a serious, contemplative expression. Smiles are rare, reflecting both the photographic conventions of the time (long exposure times made smiling difficult for photography, influencing painted portraiture) and a cultural emphasis on gravity and piety.

Emphasis on Likeness: While not always anatomically perfect by academic standards, Peck's portraits convey a strong sense of individual likeness. He captured the essential features and character of his sitters.

Flatness and Pattern: Common to folk art, Peck's figures often have a degree of flatness, with less emphasis on three-dimensional modeling through chiaroscuro (the use of light and shadow) than found in academic painting. Instead, there's often a strong sense of pattern in the rendering of clothing and decorative elements.

Distinctive Brushwork: Particularly in his later Illinois period, a characteristic "rabbit-track" or three-lobed brushstroke is often noted in the rendering of details like tassels or foliage, sometimes referred to as his "signature" stroke since he rarely signed his canvases.

Use of Color: His palette evolved from the more somber tones of his Vermont period to brighter, more varied colors in New York and Illinois. He often used bold, contrasting colors in clothing and decorative elements.

Materials: Peck commonly painted on wooden panels, especially in his earlier career, though he also used canvas. The use of wood panels was practical for an itinerant artist, being durable and relatively inexpensive.

His style can be contrasted with that of academically trained contemporaries like Gilbert Stuart or Thomas Sully, whose portraits were characterized by sophisticated modeling, rich textures, and often a more idealized or romanticized depiction of the sitter. Peck's art, like that of other folk painters such as Joseph H. Davis with his distinctive watercolor profiles, or William Matthew Prior who famously offered portraits "without shade or shadow" at a lower price point, offered a different aesthetic – one that valued clarity, directness, and a certain unpretentious charm.

Representative Works

While an exhaustive catalog is extensive, certain works are frequently cited as representative of Sheldon Peck's style and periods:

Early Vermont/New York Period: Portraits from this era, such as those of unidentified sitters, often show a darker palette and a more tentative, though still direct, approach. An example might be an early portrait of a stern-faced man or woman, painted on a wooden panel, with minimal background.

New York Period: "Anna Gould Crane and Granddaughter Janette" (c. 1830-1835), now in the collection of the American Folk Art Museum, shows his evolving style with more color and the inclusion of a painted frame element.

Illinois Period: This is his most recognized period.

"Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. William Vaughan" (c. 1840s): This pair of portraits showcases his mature style, with the characteristic direct gaze and simple, dignified presentation.

"Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Francis Almar Miller" (c. 1840s): These works are prime examples of his Illinois portraiture, capturing the likeness of a prosperous local family. Such paintings have achieved significant prices at auction, reflecting the high regard for Peck's work among collectors.

"Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Franklin Miller": Similar to the Almar Miller portraits, these would demonstrate his consistent approach to depicting married couples, often as companion pieces.

"David and Catherine Stolp" (c. 1845-1850): These portraits, now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, are iconic examples of his Illinois work, notable for their vibrant color and the distinctive decorative swags at the top.

"The Children of S. S. Jones and His Wife Junia" (c. 1851): This group portrait of children demonstrates his ability to handle more complex compositions while retaining his characteristic style.

The directness and lack of pretense in these portraits resonate with modern viewers, offering an authentic glimpse into the lives of 19th-century Americans.

Later Life, Death, and Rediscovery

Sheldon Peck continued to farm and paint in Lombard until his death from pneumonia on March 19, 1868, at the age of 70. He was buried in the Lombard Cemetery. For many years after his death, like many folk artists of his era, Sheldon Peck faded into relative obscurity. His paintings remained cherished family heirlooms but were not widely known in the broader art world.

The rediscovery and appreciation of American folk art began in the early 20th century, championed by collectors like Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and curators like Holger Cahill. However, it was not until the mid-to-late 20th century, particularly from the 1970s onwards, that Sheldon Peck's work began to receive significant scholarly attention and recognition from major museums and collectors. Exhibitions and publications helped to identify his oeuvre and establish his importance. His distinctive style, once identified, allowed art historians to attribute a growing body of work to him.

The Sheldon Peck Homestead in Lombard was acquired by the Lombard Historical Society in the 1970s. It has been meticulously restored and operates as a museum, showcasing Peck's life, his art (including some original works and reproductions), and his vital role in the Underground Railroad. It is recognized as a confirmed site on the National Park Service's Network to Freedom, a testament to his abolitionist activities.

Museums that now hold his work include the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, and many others. His paintings are highly sought after by collectors of Americana and folk art.

Legacy and Significance

Sheldon Peck's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he created a significant body of work that captures the spirit of 19th-century rural and small-town America. His portraits are valued for their aesthetic qualities – their bold designs, expressive characterizations, and unpretentious charm. He stands alongside other important American folk painters like Edward Hicks (known for his "Peaceable Kingdom" series), Joshua Johnson (one of the earliest documented professional African American painters), and Ruth Henshaw Bascom (known for her life-size pastel and cut-paper profile portraits), as a key figure in defining a distinctly American artistic voice outside the academic tradition.

As a man, Sheldon Peck exemplified the courage and moral conviction of the abolitionist movement. His willingness to risk his own safety and livelihood to aid those escaping slavery speaks volumes about his character. He was not an isolated artist but an engaged citizen, deeply involved in the great social and moral questions of his day.

His life also reflects the pioneering spirit of 19th-century America – the westward migration, the establishment of new communities, and the resourcefulness required to build a life on the frontier. He was both a farmer and an artist, a common combination for those living outside urban centers where artistic patronage was less concentrated. This dual role was shared by other artists, such as Rufus Porter, who was not only a muralist and portrait painter but also an inventor and founder of Scientific American.

Sheldon Peck's story is a reminder that art history is not solely the domain of academically trained masters working in major cultural capitals. It is also found in the honest, heartfelt creations of individuals like Peck, whose work provides invaluable insights into the diverse tapestry of American life and culture. His paintings, once hidden in family collections, now speak to a national audience, celebrating the dignity of ordinary people and the quiet heroism of a life dedicated to both art and justice. His contribution, though once "hidden," is now firmly established, ensuring his place in the annals of American art and social history. The enduring appeal of his portraits lies in their direct human connection, a quality that transcends time and continues to resonate with viewers today.