Ralph Earl stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the landscape of early American art. A portraitist and occasional landscape painter, his career spanned a tumultuous period in American history, from the burgeoning colonial unrest through the American Revolution and into the early years of the new republic. His life was marked by divided loyalties, personal struggles, and a distinctive artistic vision that blended English academic traditions with a uniquely American directness. Earl's body of work provides invaluable visual documentation of the individuals, particularly the Federalist elite of New England, who shaped the nascent United States.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born on May 11, 1751, in Worcester County, Massachusetts—some sources suggest Shrewsbury or Leicester, while others point to Lexington—Ralph Earl was the eldest son of Ralph Earl and Phebe Whittemore Earl. His father was a colonel in the Revolutionary army, a fact that would later cast his son's Loyalist sympathies into sharper relief. The Earl family later moved to New Haven, Connecticut, which became a pivotal location for the young artist's burgeoning career.

Unlike many of his European contemporaries, Earl appears to have been largely self-taught in his initial artistic endeavors. In the 1770s, he began working as an itinerant portrait painter, traveling through Connecticut and Massachusetts. This mode of operation was common for artists in colonial America, where established art academies and consistent patronage were scarce. His early style, though unrefined, showed a natural aptitude for capturing a likeness and a keen eye for detail, particularly in the rendering of costume and setting.

Around 1774, Earl married his cousin, Sarah Gates, in Worcester, Massachusetts. The couple had a daughter, Phebe, born in January 1775, and a son, John, born later that year. However, the marriage was not a lasting one, and their paths would diverge significantly, especially with the outbreak of the Revolution. It was also in 1774 that Earl established a studio in New Haven, signaling a more settled phase in his early career.

The Revolutionary Divide and English Sojourn

The American Revolution created deep divisions within colonial society, and Ralph Earl found himself on the Loyalist side, a position at odds with his father's Patriot allegiance. His Loyalist sympathies were not merely passive; he actively worked against the Patriot cause. In 1775, despite his political leanings, Earl, along with the engraver Amos Doolittle, visited the sites of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Earl created four dramatic sketches of the engagements, which Doolittle then engraved and published. These prints, among the earliest visual representations of the battles, were ironically used as Patriot propaganda, though Earl's intention may have been more documentary or even sympathetic to the British perspective of colonial aggression.

As the Revolution intensified, Earl's position as a Loyalist became increasingly untenable. In 1777 or 1778, leaving behind his wife Sarah and their children, he disguised himself as a servant to British army captain John Money and sailed for England. This move marked a crucial turning point in his artistic development. In London, Earl had the invaluable opportunity to study with the expatriate American painter Benjamin West, then Historical Painter to King George III and a towering figure in the London art world. West's studio was a hub for aspiring American artists, including John Trumbull, Gilbert Stuart, and Mather Brown.

Under West's tutelage, Earl was exposed to the prevailing Neoclassical style and the "Grand Manner" of portraiture, which emphasized idealized representations, historical or mythological allusions, and a sophisticated, polished technique. He also absorbed influences from other prominent British artists of the day, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, and Thomas Gainsborough, whose elegant portraits and landscapes were highly fashionable. John Singleton Copley, another American expatriate who had achieved great success in London, also provided a model of an American artist thriving in the competitive British art scene. Earl exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1783 and 1784, indicating a degree of professional recognition. During his seven years in England, he painted portraits of several notable figures, including Captain Money and General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. He also remarried, to Ann Whiteside (or Whitehouse), apparently without formally divorcing Sarah Gates, an act that would contribute to later controversies.

Return to America and a Maturing Style

Ralph Earl returned to the United States in 1785, accompanied by his new wife, Ann. His reasons for returning are not entirely clear but may have involved a desire to establish himself in his native land, despite his Loyalist past, or perhaps a recognition that the competition in London was too fierce. He initially settled in New York City, where he found himself imprisoned for debt from 1786 to 1788. Ironically, this period of incarceration proved artistically productive. Sympathetic patrons, including members of the Society for the Relief of Distressed Debtors, arranged for him to paint portraits while in jail, with Ann often assisting by painting the draperies and backgrounds.

Upon his release, Earl resumed his career as an itinerant painter, primarily working in Connecticut, but also taking commissions in New York, Vermont, and Massachusetts. His English training had undeniably refined his technique, lending his work greater sophistication in composition, color, and the handling of paint. However, Earl did not simply replicate the Grand Manner he had learned in London. Instead, he adapted it, forging a style that was uniquely his own and well-suited to his American clientele.

His portraits from this period are characterized by a strong sense of realism, a directness in capturing the sitter's personality, and an almost tangible rendering of textures, particularly fabrics. Unlike the often idealized and generalized settings of British Grand Manner portraiture, Earl frequently placed his subjects in specific, recognizable environments, often their own homes or landscapes relevant to their lives and status. This attention to the particular, to the details of American life and material culture, gives his work a distinctively American flavor. His figures are often somewhat stiff and linear, a characteristic that some critics attribute to a provincial naivety, but which can also be seen as a deliberate stylistic choice reflecting the sober and unpretentious character of many of his New England sitters.

Notable Portraits and Their Characteristics

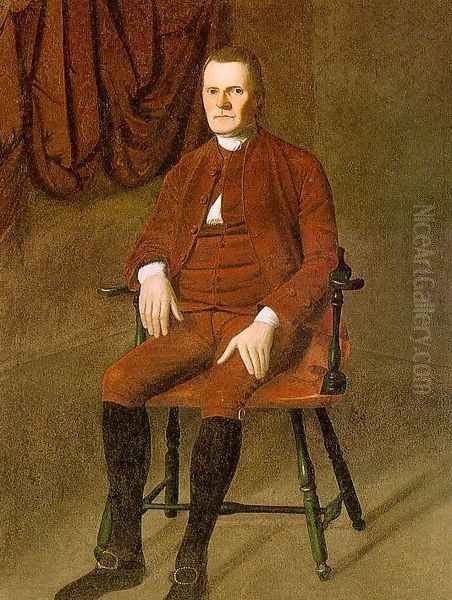

Ralph Earl's oeuvre consists of at least 183 known portraits, and his sitters were often prominent members of the Federalist elite: merchants, landowners, clergymen, and political figures. Among his most celebrated works is the Portrait of Roger Sherman (c. 1775-1777), one of his earlier significant pieces. Sherman, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, is depicted with an unadorned honesty, seated in a simple Windsor chair, conveying a sense of republican austerity and intellectual rigor. The portrait lacks the polish of his later works but possesses a powerful directness.

After his return from England, his style evolved. The Portrait of Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth and His Wife, Abigail Wolcott Ellsworth (1792) is a masterful double portrait. It showcases Earl's ability to manage complex compositions and to convey the status and relationship of his sitters. The figures are placed in a well-appointed interior, likely their home, with a view of a landscape through a window, a common motif in Earl's work that served to ground the sitters in their environment and allude to their landholdings or public service. Oliver Ellsworth, a key drafter of the Constitution and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and his wife are presented with dignity and a quiet confidence.

The portraits of the Boardman family of New Milford, Connecticut, are also exemplary. Elijah Boardman (1789) depicts the young merchant standing proudly before his dry goods store, a bolt of fabric under his arm, symbolizing his profession and prosperity. The detailed rendering of the shop and its wares provides a fascinating glimpse into the commercial life of the period. Similarly, the portraits of Colonel William Taylor (1790) and Mrs. William Taylor and Son, Daniel Boardman (1790) are notable for their rich detail and the way they convey the sitters' social standing through costume and setting. Mrs. Taylor is shown in an elegant interior with her young son, the landscape visible through the window again adding depth and context.

Other significant works include the Portrait of Benjamin Tallmadge and His Son William (1790), depicting the Revolutionary War hero and Federalist congressman with his young son, and the accompanying portrait of Mrs. Benjamin Tallmadge with Her Son Henry Floyd and Daughter Maria Jones. These paintings, like many of Earl's, emphasize family, property, and social position, reflecting the values of his patrons. His ability to capture the nuances of personality, even within the somewhat formal conventions of 18th-century portraiture, set him apart. He was less concerned with flattering his subjects in the manner of some of his European-influenced contemporaries like Gilbert Stuart, and more focused on a truthful, if sometimes stark, representation.

Landscapes and Historical Works

While primarily known as a portraitist, Ralph Earl also produced a small number of landscapes. His most ambitious undertaking in this genre was a large-scale panorama, A View of the Town of Litchfield (c. 1798-1800), though his most famous landscape is arguably his depiction of Niagara Falls. He painted at least two versions of Niagara Falls, one of which was a large panorama exhibited in 1790. These works, though perhaps not as technically sophisticated as the landscapes of European specialists like Claude Lorrain or later American artists of the Hudson River School such as Thomas Cole or Asher B. Durand, demonstrate Earl's interest in the American scene and his capacity for capturing the grandeur of nature.

His early collaboration with Amos Doolittle on the engravings of the Battles of Lexington and Concord also highlights his engagement with historical subjects, albeit at the beginning of his career. These prints, despite their somewhat crude execution by Doolittle, remain important historical documents. However, unlike his contemporary John Trumbull, who dedicated much of his career to grand historical paintings of the Revolution, Earl did not pursue this genre extensively after his return from England. His focus remained firmly on portraiture, which offered more consistent patronage in the young republic.

Personal Life, Challenges, and Controversies

Ralph Earl's personal life was fraught with difficulties and marked by behavior that was often controversial. His abandonment of his first wife, Sarah Gates, and their children to flee to England as a Loyalist was a significant transgression in the eyes of many Patriots. His subsequent marriage to Ann Whiteside while Sarah was still alive constituted bigamy, a serious offense. Though Ann accompanied him back to America and assisted in his work, he reportedly abandoned her and their children as well around 1794.

A more persistent and ultimately destructive issue was Earl's alcoholism. His struggles with "intemperance," as it was then termed, led to periods of unreliability, financial hardship, and a decline in the quality of his work in his later years. He was imprisoned for debt on more than one occasion, not just in New York but also later in Bennington, Vermont. While incarcerated, he often continued to paint to earn money for his release or to support himself.

There are anecdotes of his erratic behavior. One peculiar incident involved being fined twenty shillings for "being in the snow with his wife in an indecent posture." His Loyalist past also continued to cast a shadow, although he managed to find patronage among prominent Federalists, many of whom valued his artistic skill and perhaps shared some of his conservative political leanings. Despite these personal failings, Earl maintained a network of patrons who supported his work, suggesting that his artistic talent often overshadowed his personal indiscretions. His life illustrates the precarious existence of many artists in early America, reliant on commissions and often struggling with financial instability.

Artistic Circle and Influence

During his time in London, Ralph Earl was part of Benjamin West's circle, which, as mentioned, included future leading American artists like Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, and Mather Brown. This exposure to West's studio and the broader London art scene, with luminaries like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and George Romney dominating portraiture, was formative. He would have also been aware of the work of earlier colonial painters who had set precedents in America, such as John Smibert and Robert Feke, and the more sophisticated realism of John Singleton Copley's American period.

Upon his return to America, Earl's style, with its blend of English polish and American directness, found a niche. He was a contemporary of Gilbert Stuart, who also returned to America in the 1790s and quickly became the most sought-after portraitist, particularly for his iconic depictions of George Washington. While Stuart's style was generally more painterly, psychologically penetrating, and imbued with a fluid, almost impressionistic brushwork, Earl's was often more linear, detailed, and grounded in the material reality of his sitters' lives. Charles Willson Peale, another major figure, was active primarily in Philadelphia, known for his large family portraits, his museum, and his scientific interests, representing a different facet of American artistic and intellectual life.

Earl's influence can be seen in the work of some regional artists. For instance, Joseph Steward of Hartford, Connecticut, is known to have emulated Earl's style. More significantly, Earl's artistic legacy was continued by his son, Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl (often R.E.W. Earl), born to his second wife, Ann. R.E.W. Earl also became a portrait painter and is best known for his close association with President Andrew Jackson, becoming Jackson's "court painter" and painting numerous portraits of him and his circle. This familial continuation of the artistic profession was not uncommon in the period.

Later Years and Decline

The last decade of Ralph Earl's life, the 1790s, was his most prolific period as an itinerant painter, particularly in Connecticut and Vermont. He produced a significant number of portraits, many of which are considered among his best. However, his alcoholism increasingly took its toll. Accounts from this period suggest that the quality of his work could be uneven, likely reflecting his personal state. He continued to struggle with debt and instability.

His final years were spent in Bolton, Connecticut. Ralph Earl died there on August 16, 1801, at the age of 50. The cause of his death was officially recorded by the local minister, Reverend George Colton, as "intemperance," a stark testament to the addiction that had plagued much of his adult life. He was buried in Bolton.

Legacy and Reassessment

For many years after his death, Ralph Earl was a relatively obscure figure in American art history, overshadowed by contemporaries like Stuart and Copley. His Loyalist past and personal failings may have contributed to this neglect. However, in the 20th century, particularly with the rise of interest in American folk art and early American painting, his work underwent a significant reassessment.

Art historians and curators began to recognize the unique qualities of his portraiture: the directness, the detailed rendering of American interiors and landscapes, and the insightful characterizations of the individuals who built the new nation. His paintings came to be valued not just as likenesses but as rich historical documents, offering insights into the material culture, social aspirations, and self-perception of post-Revolutionary America. His work is seen as a bridge between the more formal, English-influenced colonial style and a more distinctly American approach to portraiture.

Today, Ralph Earl's paintings are held in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Yale University Art Gallery, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, and the Worcester Art Museum. Exhibitions of his work have further solidified his reputation as a key artist of the Federal period. While his life was marked by turmoil and contradiction, his art provides a compelling and enduring vision of his time. He captured the faces and the world of a generation navigating the complexities of independence and nation-building, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of early American identity. His ability to adapt sophisticated European techniques to the tastes and values of his American patrons, combined with his keen observational skills, ensures his place as an important, if complex, contributor to the story of American art.