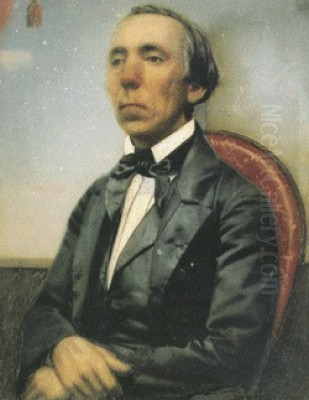

Erastus Salisbury Field stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the landscape of 19th-century American art. Born in a period of nascent national identity and active through decades of profound societal transformation, Field’s extensive body of work offers a unique window into the lives, aspirations, and anxieties of his time. Primarily recognized as a folk artist, his contributions span from intimate portraits of New England families to ambitious, imaginative historical and biblical allegories. His career, marked by an early, brief tutelage under a renowned master and a long, largely self-directed path, reflects both the opportunities and limitations faced by artists outside the established academic circles of his era. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, key works, and enduring legacy of a painter who captured the spirit of a changing America with a distinctive and compelling vision.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Erastus Salisbury Field was born on May 19, 1805, in Leverett, Massachusetts, a small rural town that would remain a touchstone throughout his long life. He was one of three children, with two younger sisters, Salome and Allison. His upbringing in this modest New England setting undoubtedly shaped his early perceptions and, perhaps, his affinity for depicting the unvarnished realities of rural and middle-class life. The region itself was steeped in a Puritan heritage, a cultural undercurrent that would later manifest in the moral and biblical themes of his more ambitious compositions.

The precise origins of Field's artistic inclinations are not extensively documented, but it is clear that by his late teens, his talent was evident enough to warrant formal training. In 1824, at the age of nineteen, Field made the journey to New York City, a burgeoning center for arts and commerce. There, he entered the studio of Samuel F. B. Morse, a figure already distinguished as a painter and who would later achieve global fame as the inventor of the telegraph. Morse, a student of Benjamin West and Washington Allston, was a proponent of the grand manner of historical painting, though he also excelled at portraiture, a more commercially viable genre in the young republic.

Field's time with Morse, however, was unexpectedly brief. After only three months of study, he was compelled to return to Leverett. The reasons for this short tenure are often attributed to financial constraints or perhaps family obligations. Regardless of the cause, this truncated academic experience meant that Field, for the most part, would develop his skills and artistic vision independently, aligning him more closely with the tradition of self-taught or "folk" artists who flourished in America during this period.

The Itinerant Portraitist: Capturing a New England Likeness

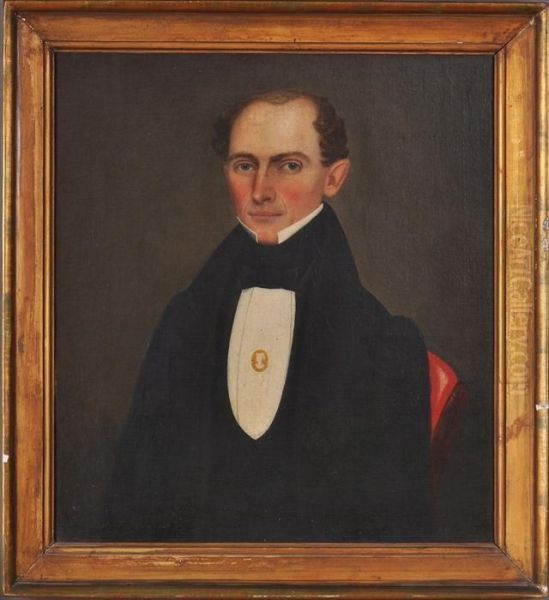

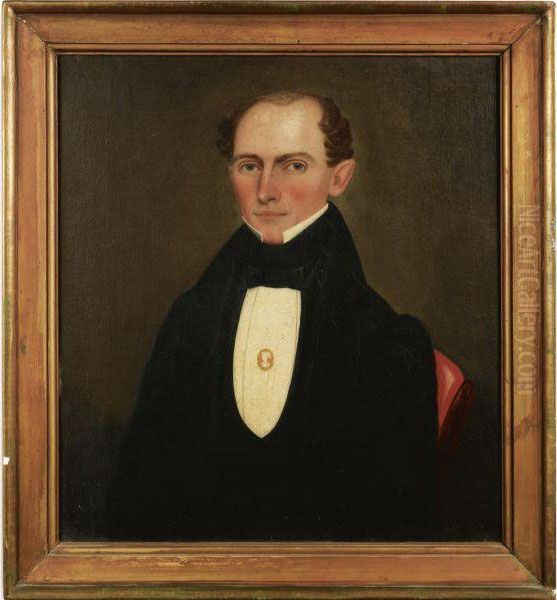

Upon his return to Massachusetts in 1825, Erastus Salisbury Field embarked on a career as an itinerant portrait painter. This was a common path for many artists in early 19th-century America, particularly those outside the major urban centers. These traveling artists journeyed from town to town, seeking commissions from families eager to have their likenesses preserved. Field primarily worked in western Massachusetts and the Connecticut River Valley, leveraging family connections and word-of-mouth to secure patronage among the reasonably affluent rural and small-town populace.

His clients were typically members of the emerging middle class – farmers, merchants, local dignitaries, and their families – who sought in portraiture a mark of their status and a record for posterity. Field’s early portraits from this period, roughly spanning the 1820s and 1830s, are characterized by a directness and a certain charming stiffness often associated with folk art. He demonstrated a keen eye for detail, meticulously rendering clothing, hairstyles, and domestic accessories, which provide valuable insights into the material culture of the time.

Works such as Portrait of a Young Lady (circa 1830) or group portraits like Joseph Moore and His Family (1839) exemplify his style during this phase. The figures are often presented frontally or in three-quarter view, with a focus on clear delineation of form rather than sophisticated modeling or atmospheric effects. There's an earnestness in his attempt to capture a true likeness, even if anatomical precision sometimes yielded to a more stylized representation. His sitters often exude a sense of quiet dignity and rural self-possession, reflecting the values of their communities. Field's palette was generally sober, with occasional flashes of brighter color in costume details or background elements.

Characteristics of Field's Early Portraiture

The portraits created by Erastus Salisbury Field during his itinerant phase possess several distinguishing characteristics that place them firmly within the American folk art tradition, yet also hint at his individual approach. One notable feature is the almost palpable presence he imbues in his sitters. Despite a lack of academic polish in rendering anatomy or complex perspective, his subjects often engage the viewer with a direct, unwavering gaze. This directness lends an air of honesty and unpretentiousness to the portrayals.

Field paid considerable attention to the accoutrements of his subjects. Lace collars, patterned textiles, jewelry, books, and even furniture were rendered with a careful, almost documentary precision. In some instances, as noted in art historical accounts, he would even include itemized lists of possessions within the composition, underscoring the pride of ownership and the material aspirations of the burgeoning middle class he served. This meticulous attention to detail not only provided visual interest but also served to contextualize the sitters within their domestic and social environments.

Compared to academically trained contemporaries like Thomas Sully or Chester Harding, who aimed for a more idealized and painterly European style, Field’s work was less concerned with bravura brushwork or flattering idealization. Instead, he offered a more literal, though often stylized, interpretation. His figures can appear somewhat flat, with a strong emphasis on outline and pattern, characteristics shared with other folk painters of the era such as Ammi Phillips or Sheldon Peck, who also served similar New England communities. However, Field often managed to convey a subtle psychological insight, capturing a sense of individual personality despite the formal constraints of his style.

The Rise of Photography and a Shift in Focus

The 1840s and 1850s brought a technological innovation that would profoundly impact the world of portraiture: the daguerreotype and subsequent photographic processes. Photography offered a quicker, often cheaper, and arguably more "accurate" means of capturing a likeness than painting. This development significantly diminished the demand for itinerant portrait painters like Field. While some artists struggled to adapt, Field demonstrated a degree of flexibility.

He did not abandon painting entirely but began to explore other avenues. For a period, he himself engaged with the new medium, working as a daguerreotypist. There is evidence of his collaboration with Abram Bogardus, a prominent New York photographer, suggesting Field was keen to understand and perhaps integrate this new technology into his artistic practice. This experience with photography may have influenced his later painted portraits, some of which exhibit a heightened realism or a compositional sense that echoes photographic conventions.

However, the decline in portrait commissions also seems to have liberated Field to explore subjects beyond individual likenesses. It was during the mid-century and later that he increasingly turned his attention to historical, biblical, and allegorical themes. This shift allowed him to express more personal visions and engage with broader cultural and moral narratives, moving away from the client-driven nature of portraiture towards more imaginative and ambitious compositions. This transition marks a significant evolution in his artistic journey, leading to some of his most distinctive and complex works.

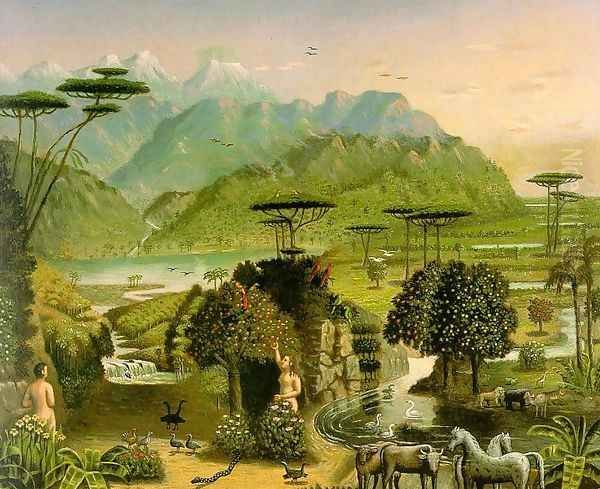

Exploring Historical and Biblical Narratives

As the demand for painted portraits waned with the advent of photography, Erastus Salisbury Field channeled his creative energies into historical and biblical subjects. These works allowed him a broader canvas for his imagination and a platform to engage with the grand narratives that shaped Western culture and American identity. His interpretations were often idiosyncratic, blending traditional iconography with his unique folk sensibility and a strong moral undertone, likely influenced by his New England Protestant upbringing.

Among his notable works in this vein is the Plagues of Egypt Series. These paintings depict the dramatic and often terrifying scenes from the Book of Exodus with a vividness and directness that is characteristic of Field's style. While perhaps lacking the sophisticated compositional structures or anatomical mastery of academically trained historical painters like Emanuel Leutze (famous for Washington Crossing the Delaware) or the dramatic flair of European masters, Field's biblical scenes possess a raw power and narrative clarity. He focused on the core emotional and spiritual impact of the stories, rendering them accessible and compelling.

His historical paintings often touched upon themes relevant to American identity and contemporary concerns. While not as overtly political as some artists, his choice of subjects and their treatment could reflect prevailing sentiments or offer subtle commentary. This period of his work demonstrates a mind grappling with large ideas – faith, history, morality, and the human condition – expressed through a visual language that remained rooted in his self-taught, direct approach. This foray into narrative painting set the stage for his most ambitious, though ultimately unrealized, conceptual project.

The Historical Monument of the American Republic: A Grand Vision

Perhaps the most famous and certainly the most ambitious undertaking of Erastus Salisbury Field's career was his monumental painting, The Historical Monument of the American Republic. Conceived around the time of the nation's Centennial in 1876, this massive canvas (approximately 9 by 13 feet) depicts an elaborate architectural fantasy, a towering structure meant to symbolize the history and progress of the United States. Field reportedly began working on the idea in response to a competition for a central architectural feature for the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1874, though he was not a trained architect.

The painting envisions a series of interconnected, ornately decorated towers, rising to a colossal height, estimated to be around 500 feet if realized. These towers are adorned with sculptures, inscriptions, and narrative reliefs illustrating key events and figures from American history, from its discovery and colonization through the Civil War and into the technological advancements of the 19th century. Steam trains are even depicted running on tracks that spiral around and through the structure, symbolizing progress and ingenuity. The monument is crowned with allegorical figures and symbols representing American ideals.

Field’s vision for the Historical Monument was deeply personal and imbued with his own interpretations of American history, including its triumphs and its moral complexities, such as slavery and government corruption, alongside celebrations of Puritan spirit and biblical righteousness. Although the monument itself was never built – the technological and financial resources required for such a concrete structure were prohibitive at the time – the painting remains a powerful testament to Field's imaginative capacity and his profound engagement with the narrative of his nation. It stands as a unique piece of American visionary art, a folk artist's grand, patriotic, and didactic dream. The painting is now a centerpiece of the collection at the Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Field and His Contemporaries: A Comparative Landscape

Understanding Erastus Salisbury Field's place in American art history is enriched by considering him in relation to his contemporaries. His initial teacher, Samuel F.B. Morse, was part of an earlier generation that included figures like Gilbert Stuart and Thomas Sully, artists who brought a more European, academic sensibility to American portraiture. Field’s brief exposure to Morse provided a foundational, if limited, glimpse into this world, but his subsequent development took a distinctly different path.

As an itinerant folk painter, Field shared more in common with artists like Ammi Phillips, Rufus Porter, William Matthew Prior, and Sheldon Peck. These artists, often self-taught or minimally trained, served a similar clientele in rural New England and New York, producing portraits characterized by directness, strong design, and a focus on likeness and detail over academic convention. While their styles varied, they collectively created a rich visual record of 19th-century American life outside the elite circles of major cities. Joseph H. Davis, another contemporary folk artist, was known for his charming watercolor profiles, often including detailed domestic interiors, a different medium but a similar focus on capturing the sitter's environment.

When Field shifted towards historical and landscape subjects, he was working in an era dominated by the Hudson River School, led by painters such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, who celebrated the American wilderness with romantic grandeur. While Field’s landscapes were less panoramic and more stylized, they shared a certain reverence for the American scene. His historical narratives can be loosely compared to the more academic works of painters like Emanuel Leutze or Eastman Johnson, though Field’s approach was far less conventional and more personal. The rise of photography, with figures like Mathew Brady documenting the Civil War and American life, also provides a crucial context for Field's later career and his own experiments with the medium. Even later, the raw, expressive portraiture of 20th-century artists like Alice Neel, with whom Field's work has been posthumously exhibited, shares a certain unvarnished honesty, albeit from a vastly different stylistic and temporal perspective.

Later Years and Continued Artistic Pursuits

Even as he aged, Erastus Salisbury Field remained artistically active. The latter part of the 19th century saw him continue to reside primarily in the Leverett area, specifically in a section known as the "Plumtrees" in Sunderland, where he had a farm and studio. While the grand vision of the Historical Monument of the American Republic remained a painting rather than a physical structure, it is believed he continued to refine and work on it for many years, a testament to its significance in his artistic and intellectual life.

His output in these later decades included further explorations of biblical and historical themes, as well as landscapes and occasional portraits. The influence of photography, which he had engaged with earlier in his career, may have continued to subtly inform his approach to representation, perhaps in the sharpness of detail or the way figures were posed. However, his fundamental style, rooted in the folk tradition, remained largely consistent, characterized by strong outlines, a vibrant, if sometimes unconventional, use of color, and a direct, narrative approach.

Field lived to the remarkable age of 95, passing away on June 28, 1900. His long life spanned almost the entirety of the 19th century, a period of immense change in America – from a young, largely agrarian republic to an industrialized nation on the cusp of global power. His art, in its own distinct way, chronicled aspects of this transformation, from the faces of its citizens to its grand historical narratives and moral preoccupations. He left behind a substantial body of work, estimated at around 400 paintings, a legacy of a dedicated and imaginative artist.

Artistic Legacy and Re-evaluation

For many years after his death, Erastus Salisbury Field, like many folk artists of his generation, remained relatively obscure within mainstream art historical narratives, which tended to prioritize academically trained artists and established movements. However, the early 20th century saw a growing appreciation for American folk art, spearheaded by collectors like Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and curators like Holger Cahill, who organized the influential exhibition American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man at the Museum of Modern Art in 1932. This burgeoning interest helped bring artists like Field into the scholarly and public eye.

Field's work came to be valued for its directness, its vibrant depiction of 19th-century American life, and its unique imaginative qualities. His portraits are prized for their historical value, offering insights into the appearance, attire, and domestic settings of ordinary Americans. His more ambitious historical and biblical paintings, particularly The Historical Monument of the American Republic, are recognized as remarkable examples of visionary art, demonstrating a powerful, if untutored, creative force.

While art historians acknowledge certain "limitations" in his work when judged by academic standards – such as occasional awkwardness in anatomy or perspective – these are often seen as part of the distinctive charm and power of his folk style. His ability to capture the character of his sitters and to convey complex narratives with clarity and conviction is widely recognized. Today, Field is considered one of the foremost American folk painters of the 19th century. His works are held in major museum collections, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and prominently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, Massachusetts, which houses a significant collection of his art, including the Historical Monument.

Exhibitions and Scholarly Attention

The posthumous recognition of Erastus Salisbury Field has been significantly bolstered by dedicated exhibitions and scholarly publications. A pivotal moment was the 1984 retrospective exhibition and accompanying catalogue, Erastus Salisbury Field 1805-1900, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, Massachusetts, and guest-curated by Mary Black. This comprehensive show and publication did much to solidify his reputation and provide a thorough overview of his life and work.

His paintings have been included in numerous group exhibitions focusing on American folk art and 19th-century American painting. For instance, his work was featured in the aforementioned 1932 MoMA exhibition, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900. More recently, exhibitions have continued to explore his contributions. An interesting example is Painting the People: Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field, held at the Bennington Museum in Vermont, which created a dialogue between Field's 19th-century folk portraits and the psychologically charged 20th-century portraits of Alice Neel, highlighting unexpected continuities in their focus on capturing the human subject.

Scholarly articles in publications like Art in America and books such as Erastus Salisbury Field: A Journey Through American Art, edited by Clair Robertson, have further analyzed his oeuvre. His Historical Monument of the American Republic has been the subject of particular fascination, sometimes referred to as "The Eighth Wonder of Erastus Salisbury Field," and is frequently discussed in studies of American visionary art and national symbolism. The ongoing scholarly attention and inclusion of his work in museum collections and exhibitions ensure that Field's unique artistic voice continues to be heard and appreciated.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Americana

Erastus Salisbury Field's artistic journey offers a compelling narrative of resilience, adaptation, and unwavering creative vision. From his beginnings as an itinerant portraitist capturing the likenesses of New England's burgeoning middle class to his later, more ambitious explorations of history, religion, and national identity, Field crafted a body of work that is both a valuable historical document and a testament to the power of self-taught artistry. His paintings, characterized by their directness, meticulous detail, and imaginative scope, provide a distinctive lens through which to view 19th-century America.

While the grand architectural dream of The Historical Monument of the American Republic never materialized in stone and concrete, the painting itself endures as a powerful symbol of his ambition and his deep engagement with the American story. Field’s legacy lies not only in the individual charm and historical significance of his portraits but also in the broader, often idiosyncratic, vision he brought to his narrative works. He remains a key figure in the canon of American folk art, an artist whose dedication to his craft and whose unique perspective on his world continue to resonate with audiences and scholars alike, securing his place as a chronicler of and a contributor to the rich tapestry of American visual culture.