José Gutiérrez Solana y Gutiérrez-Solana (1886–1945) stands as one of Spain's most compelling and distinctive artistic figures of the early 20th century. A painter, writer, and printmaker, Solana carved a unique niche for himself with his stark, expressionistic portrayals of what he termed "La España Negra" or "Black Spain." His work delves into the underbelly of Spanish society, exploring themes of death, poverty, popular festivals, and the often-grim realities of everyday life with an unflinching, almost brutal honesty. His art, while deeply rooted in Spanish traditions, resonates with the broader currents of European Expressionism, offering a profound and often unsettling vision of the human condition.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

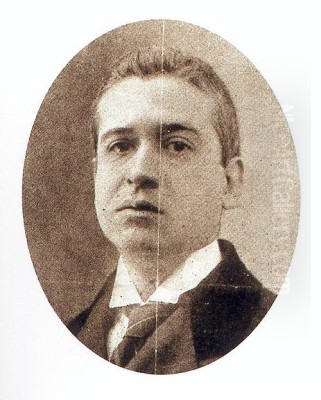

Born in Madrid on February 28, 1886, into a family with connections to Mexico (his father, José Solana, was born there, and his mother, Manuela Gutiérrez-Solana, was from Cantabria), Solana's early life was marked by a burgeoning interest in the visual arts. His formal artistic education began at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid, an institution that had nurtured generations of Spanish masters. Even during his student years, Solana demonstrated a predilection for subjects drawn from the everyday life of Madrid, particularly its more somber and marginal aspects.

His uncle, a notable figure in his youth, was the physician and writer Tomás Pellicer. This familial connection to both science and literature perhaps subtly influenced Solana's own keen observational skills and his later foray into writing. The Madrid of his youth, a city of stark contrasts, provided ample material for his developing artistic sensibility. He was drawn to the bustling markets, the quiet cemeteries, the raucous taverns, and the solemnity of religious processions, all of which would become recurring motifs in his oeuvre.

The Genesis of "España Negra"

The concept of "España Negra" (Black Spain) is central to understanding Solana's artistic and literary output. This term, which he also used as the title for one of his most significant books, refers to a vision of Spain characterized by its deep-seated traditions, its popular piety often tinged with superstition, its stark social realities, and a pervasive sense of fatalism and tragedy. It is a Spain of shadows, of intense but often somber emotions, and of a raw, unvarnished humanity.

Solana's "España Negra" is not merely a geographical or cultural descriptor; it is an existential landscape. His paintings from this thematic vein are populated by bullfighters, prostitutes, carnival revellers, mourners, sailors, and an array of characters from the fringes of society. He depicted scenes in slaughterhouses, ports, cheap cafes, and during religious festivals with a directness that could be shocking to some of his contemporaries. His palette often leaned towards dark, earthy tones – ochres, browns, blacks, and deep reds – punctuated by stark whites or unsettling flashes of color, enhancing the dramatic and often melancholic mood of his works.

Artists like Francisco de Goya, particularly his "Black Paintings" and social caricatures in Los Caprichos, served as a profound spiritual predecessor for Solana. The grotesque, the critique of societal ills, and the exploration of the darker aspects of human nature found in Goya's work echo powerfully in Solana's canvases. Another significant influence was El Greco, whose elongated figures and intense spirituality, albeit transformed by Solana into a more secular, existential angst, can be felt in the dramatic compositions and emotional weight of his figures.

Key Thematic Concerns in Solana's Art

Solana's body of work is remarkably consistent in its thematic preoccupations. He returned to certain subjects repeatedly, exploring their different facets and deepening his unique vision.

The Spectacle of Life and Death

Death is an omnipresent theme in Solana's art. He depicted funerals, cemeteries, and the memento mori with a stark realism that avoided sentimentality. Works like El entierro de la sardina (The Burial of the Sardine), a subject famously tackled by Goya, capture the bizarre and macabre energy of Spanish carnival traditions, where revelry and mortality often intertwine. The bullfight, another quintessential Spanish spectacle, appears frequently, often focusing not on the glamour but on the raw, brutal aspects of the confrontation between man and beast, or the grim reality of the desolladero (flaying house).

His fascination extended to the objects associated with these rituals. Wax figures, anatomical models, and religious effigies, often found in popular settings or old museums, appear in his still lifes and genre scenes, blurring the lines between the animate and inanimate, the sacred and the profane. These objects, for Solana, seemed to hold a silent testimony to human existence and its transience.

The World of the Marginalized

Solana possessed a deep empathy, or at least a profound fascination, for those living on the margins of society. His paintings are a veritable gallery of "types": the old sailor, the street vendor, the chorus girl, the down-and-out intellectual. He portrayed them without romanticization, capturing their weariness, their resilience, or their quiet despair. Scenes set in the Rastro, Madrid's famous flea market, or in the bustling, often chaotic, port districts, are filled with these figures, each contributing to a collective portrait of a Spain often overlooked by more academic or idealized art.

His interest in these characters was not merely picturesque. It reflected a deeper engagement with social realities, with the struggles of the working class, and with the inherent dignity he found in individuals often dismissed by polite society. This focus aligns him with other Spanish artists who explored social themes, such as Isidre Nonell, who depicted Barcelona's gypsy communities and impoverished figures with a similar, though stylistically different, intensity.

Masks, Masquerade, and the Grotesque

Masks are a recurring and highly symbolic motif in Solana's work, most notably in his carnival scenes but also in more enigmatic compositions. An anecdote often recounted is a childhood experience where a masked intruder entered his home, an event that purportedly left a lasting impression. Beyond this personal connection, masks in Solana's art function on multiple levels. They represent the traditions of carnival, the suspension of social norms, and the embrace of the grotesque.

However, they also hint at themes of deception, hidden identities, and the often-frightening reality lurking beneath a festive facade. His figures in masks can appear comical, menacing, or simply inscrutable. This fascination with the masked and the grotesque again links him to Goya, particularly the Disparates and the carnival scenes. The use of masks and wax figures allowed Solana to explore the unsettling nature of identity and the thin veil between reality and illusion, life and artifice.

Artistic Style and Technique

Solana's style is unmistakably his own, characterized by a robust, almost sculptural application of paint and a somber, earthy palette. He favored thick impasto, building up surfaces that have a tangible, weighty presence. His brushwork is vigorous and direct, eschewing finesse for expressive power. This technique contributes to the raw, unvarnished quality of his imagery.

His compositions are often densely packed, with figures crowded together, creating a sense of claustrophobia or intense, shared experience. He had a remarkable ability to capture the atmosphere of a place, be it the dimly lit interior of a tavern or the chaotic energy of a street festival. While often described as an Expressionist, Solana's work also retains strong elements of realism, a "realismo crudo" (raw realism) that is deeply Spanish in its tradition, harking back to painters like Jusepe de Ribera or even Velázquez in his early bodegones.

The darkness in his paintings is not merely a matter of color choice; it is an essential part of their emotional and psychological impact. This "tenebrism," reminiscent of Baroque masters, serves to highlight figures and objects, throwing them into stark relief and imbuing them with a dramatic, often unsettling, presence. His figures, though sometimes appearing as types, possess a strong individual character, often conveyed through their posture, their worn faces, and their expressive, if often downcast, eyes.

Literary Endeavors: "La España Negra" and Other Writings

Solana was not only a painter but also a significant writer. His literary work is a natural extension of his visual art, exploring similar themes and milieus. His most famous book, La España Negra (1920), is a collection of essays and vignettes that paint a vivid picture of the Spain he observed on his travels and in his daily life. It is a literary equivalent of his paintings, filled with descriptions of popular customs, forgotten trades, eerie locales, and encounters with peculiar individuals.

His writing style is direct, unadorned, and rich in sensory detail, much like his painting. He also wrote other books, including Madrid: escenas y costumbres (Madrid: Scenes and Customs), further documenting the life of his beloved city. These texts are invaluable not only as literary works in their own right but also as a commentary on his artistic vision, providing insights into the sources of his inspiration and the way he perceived the world around him. His prose, like his painting, is marked by a profound sense of observation and an ability to find the extraordinary in the ordinary, the tragic in the mundane.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Solana's Unique Path

While Goya and El Greco are the most frequently cited historical influences on Solana, one can also see affinities with the vanitas tradition of Spanish Baroque painters like Juan de Valdés Leal, with their stark reminders of mortality. The unflinching realism of 17th-century masters such as Jusepe de Ribera, in his depictions of saints and common folk, also finds an echo in Solana's commitment to portraying unidealized reality.

Among his contemporaries, Solana maintained a somewhat isolated position, though he was not entirely disconnected from the artistic currents of his time. He was friends with the writer Ramón Gómez de la Serna, a key figure in the Spanish avant-garde, and famously depicted the literary gatherings at the Café de Pombo in his painting La tertulia del Café de Pombo. This work is a significant document of the intellectual life of Madrid in the early 20th century, featuring portraits of Gómez de la Serna and other writers and artists.

He also knew and was respected by other painters, such as Ignacio Zuloaga, another artist who, though in a different style, also engaged with themes of Spanish identity and tradition. However, Solana's deeply personal and often somber vision set him apart from the brighter, more optimistic art of someone like Joaquín Sorolla, or the more radical formal experiments of Cubism being pioneered by Spaniards like Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris, or the Surrealism that would later be championed by Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró.

While Spanish art in the early 20th century was experiencing a ferment of modernism, Solana largely remained committed to his own figurative, expressionistic path. His work can be seen in dialogue with international Expressionist movements, sharing with artists like Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde, or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner a concern with subjective experience, psychological depth, and a critical or melancholic view of modern life. The social critique inherent in the work of German Expressionists like Käthe Kollwitz or George Grosz also resonates with Solana's focus on the dispossessed and the harsh realities of urban existence.

Despite his unique path, Solana did achieve recognition during his lifetime, exhibiting his work both in Spain and internationally, including at the Venice Biennale and the Paris World's Fair. However, his art, with its often challenging subject matter and somber aesthetic, did not always find favor with the broader public or official institutions in Spain, which sometimes preferred more decorative or idealized representations of Spanish life.

Anecdotes and the Man Behind the Canvas

Several anecdotes illuminate Solana's personality and his deep connection to his subject matter. His solitary nature is often remarked upon. Despite his connections within Madrid's intellectual circles, he cultivated an image of an observer, somewhat detached, yet deeply immersed in the worlds he depicted. His self-portraits often convey this sense of a brooding, introspective individual.

The aforementioned childhood incident with the masked intruder is frequently cited as a formative experience, possibly fueling his lifelong fascination with masks and the unsettling power of hidden identities. This interest was not merely academic; he was an avid collector of masks, wax figures, and other curiosities that populated his studio and often found their way into his paintings, imbuing them with a strange, almost fetishistic quality.

His dedication to his subjects was profound. He would spend hours, even days, observing scenes in the Rastro, in slaughterhouses, or during popular festivals, absorbing every detail before committing it to canvas or paper. This meticulous observation, combined with his expressive technique, gives his work its powerful sense of authenticity. He was known to be a man of routine, often walking the same routes through Madrid, constantly seeking out the scenes and characters that defined his "España Negra."

Despite the darkness of much of his subject matter, there is also a deep humanism in Solana's work. He respected the working class and the common people he depicted, seeing in their struggles and their traditions a vital, if often tragic, aspect of Spanish identity. His art can be seen as a form of social commentary, though he rarely engaged in overt political activism. His critique was more existential, focused on the enduring human condition rather than specific political ideologies.

Solana's Place in Spanish Art History

José Gutiérrez Solana occupies a significant, if somewhat singular, position in the landscape of Spanish art. He is undeniably one of the foremost exponents of Expressionism in Spain, a movement that, while not as dominant there as in Germany or Austria, found powerful individual voices. His commitment to depicting the "España Negra" makes him a crucial chronicler of a particular vision of Spanish culture and society, one that acknowledges its shadows and its complexities.

During his lifetime, his work was sometimes misunderstood or undervalued, particularly by those who favored more optimistic or avant-garde styles. However, his unwavering commitment to his personal vision and his powerful, distinctive style earned him the respect of many fellow artists and critics. Posthumously, his reputation has grown, and he is now widely recognized as a major figure in 20th-century Spanish art.

His influence can be seen in later generations of Spanish artists who have continued to explore themes of social reality, identity, and the darker aspects of the human psyche. His work serves as a vital link between the tradition of Goya and the more contemporary explorations of Spanish identity in art. Artists like Antonio Saura or some aspects of the " tremendismo" literary movement share a certain affinity with Solana's unflinching gaze.

His paintings and writings offer a rich, multifaceted portrait of Spain during a period of significant social and cultural change. They challenge idealized notions of Spanishness and instead present a more complex, often unsettling, but ultimately deeply human vision.

Social Commentary and Political Undertones

While Solana was not an overtly political artist in the sense of creating propaganda or aligning himself with specific political movements, his work is imbued with a profound social consciousness. His depictions of poverty, labor, and the lives of marginalized individuals inherently carry a critical edge. By choosing to focus on these subjects, he implicitly questioned the social structures and inequalities of his time.

Works like El Rastro or The Slaughterhouse are not merely picturesque scenes; they are documents of a social reality. His portrayal of the harsh conditions of workers or the grim atmosphere of certain urban spaces speaks to a concern for social justice. The "España Negra" he depicted was, in part, a product of historical and economic forces, and his art serves as a testament to the human cost of these forces.

His critical stance was often directed towards the superficiality of bourgeois society and the perceived loss of authentic traditions in the face of modernization. However, his critique was rarely didactic. Instead, it was embedded in the very fabric of his imagery, in the expressions of his figures, and in the somber atmosphere of his canvases. His political statement, if any, was one of empathy for the downtrodden and a deep skepticism towards facile optimism or societal pretense.

Market Performance and Collection

Specific, consolidated data on José Gutiérrez Solana's auction market performance requires specialized art market analysis and database access, which typically falls outside general art historical overviews. Like many artists whose work is deeply national yet possesses universal themes, his pieces appear in auctions, particularly in Spain, and are held in major public and private collections. The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, for instance, holds a significant collection of his works, underscoring his importance in the national narrative of Spanish art. The valuation of his works would depend on factors such as period, subject matter, size, condition, and provenance, as is standard in the art market. His status as a key figure of Spanish Expressionism ensures continued interest from collectors and institutions.

Legacy and Conclusion

José Gutiérrez Solana died in Madrid on June 24, 1945. He left behind a powerful and cohesive body of work that continues to resonate with audiences today. His unflinching portrayal of "Black Spain," his mastery of a somber, expressive style, and his profound engagement with the human condition secure his place as one of the most important Spanish artists of the 20th century.

His art is a testament to the enduring power of a singular vision, one that dared to look into the shadows and find there not only darkness but also a profound and often unsettling beauty. He was a chronicler of the everyday, the marginal, and the forgotten, and in doing so, he created a world that is uniquely his own, yet speaks to universal human experiences of suffering, resilience, and the search for meaning in a complex world. Solana's legacy is that of an artist who, with profound integrity and artistic power, gave visual and literary form to a crucial, if often overlooked, dimension of the Spanish soul. His work remains a vital touchstone for understanding the rich and often contradictory tapestry of Spanish culture.