Ángel Lizcano y Monedero (1846-1929) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th and early 20th-century Spanish art. Born in Alcázar de San Juan, in the province of Ciudad Real, and passing away in Leganés, near Madrid, Lizcano's artistic journey spanned a period of profound transformation in Spain, both socially and artistically. He distinguished himself as a versatile painter, adept at capturing the essence of Spanish culture through historical narratives, vibrant bullfighting scenes, and intimate costumbrista (genre) paintings. His dedication to his craft earned him recognition in national exhibitions and a lasting place in the annals of Spanish art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the heart of La Mancha in 1846, Ángel Lizcano y Monedero's early environment would have been steeped in the rich cultural tapestry of central Spain. While specific details of his earliest artistic inclinations are not extensively documented, it is typical for artists of his generation to have shown promise early on, often receiving initial instruction locally before seeking more formal training. The mid-19th century in Spain was a period where artistic education was becoming increasingly formalized, with the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando) being the premier institution.

It is highly probable that Lizcano, like many aspiring artists of his time, made his way to Madrid to hone his skills. There, he would have been exposed to the prevailing academic traditions, which emphasized rigorous drawing, anatomical study, and the emulation of Old Masters. Figures such as Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz, a dominant force in Spanish art and director of the Prado Museum for a significant period, would have shaped the academic environment. The curriculum would have included copying classical sculptures and paintings by masters like Velázquez, Murillo, and, importantly for Lizcano's later development, Francisco Goya.

The Artistic Milieu: Influences and Styles

Lizcano's career unfolded against a backdrop of diverse artistic currents. The legacy of Romanticism was still potent, particularly the uniquely Spanish iteration influenced by Goya. Concurrently, Historicism, with its grand depictions of national history, dominated official salons and competitions. Towards the latter part of his career, Realism and the early stirrings of Impressionism and modernism began to challenge established norms.

Lizcano's work shows an intelligent synthesis of these influences. He is often considered part of a "second generation of Goyaesque painters," artists who looked to Goya not just for subject matter – the bullfights, the popular types, the critique of society – but also for a certain expressive freedom and a departure from strict academic smoothness. The influence of Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (often confused with or related to Eugenio Lucas Padilla or Villamil), a key figure in Spanish Romanticism known for his Goya-inspired scenes, is palpable in Lizcano's dynamic compositions and sometimes dramatic use of light and shadow. Another painter whose work resonates with similar themes of Spanish life was Leonardo Alenza y Nieto, an earlier costumbrista painter whose depictions of popular Madrid life set a precedent.

While embracing the vibrancy of Romanticism, Lizcano also engaged with the narrative demands of historical painting. However, his approach often sought a more human, less grandiose portrayal than some of his contemporaries known for monumental historical canvases, such as Francisco Pradilla Ortiz or Antonio Gisbert Pérez. Lizcano's historical scenes, while accurate in detail, often focused on the human element within the larger event.

A significant aspect of Lizcano's style is his deep connection to costumbrismo. This genre, dedicated to depicting the everyday life, customs, and traditions of ordinary people, was immensely popular in 19th-century Spain. It offered a way to define and celebrate national identity. Lizcano excelled in this area, capturing market scenes, local festivities, and rural life with an observant eye and a sympathetic brush. His work in this vein can be compared to that of Valeriano Domínguez Bécquer, another renowned costumbrista painter.

Key Themes in Lizcano's Oeuvre

Ángel Lizcano y Monedero's artistic production can be broadly categorized into several key thematic areas, each reflecting different facets of his skill and interests.

Historical Paintings

Historical painting was highly esteemed in the 19th century, often seen as the pinnacle of artistic achievement. Lizcano contributed to this genre, though perhaps not on the same epic scale as some of his contemporaries. His historical works often focused on significant moments or figures from Spanish history, rendered with attention to period detail but also imbued with a narrative clarity that made them accessible. These paintings served not only as artistic endeavors but also as visual lessons in national heritage, a common goal for historical painters of the era.

Bullfighting Scenes (Tauromaquia)

The bullfight, a quintessential element of Spanish culture, was a recurring and powerful theme in Lizcano's work. Following in the tradition of Goya, and later artists like Mariano Fortuny Marsal (though Fortuny's style was more polished and internationally flavored), Lizcano captured the drama, danger, and spectacle of the corrida. His bullfighting paintings are noted for their dynamic compositions, energetic brushwork, and ability to convey the intense atmosphere of the arena. Works titled "Corrida de toros" (Bullfight Scene) are representative of his engagement with this subject, showcasing his understanding of the ritual and his skill in depicting movement and emotion. These scenes were popular with both Spanish and international audiences, eager for depictions of this iconic Spanish tradition.

Costumbrismo and Genre Scenes

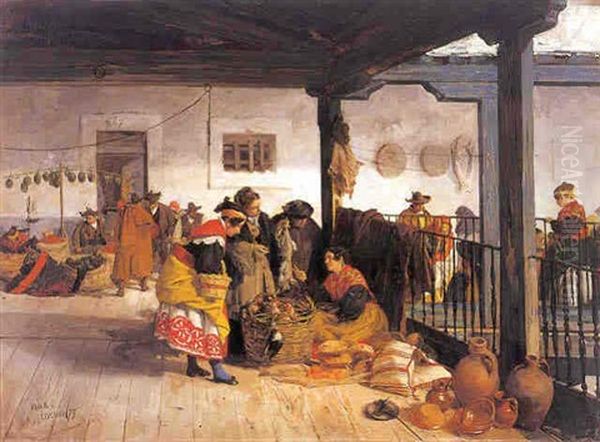

Perhaps where Lizcano's personal voice shone most clearly was in his costumbrista or genre scenes. These paintings offer a window into the daily life of 19th-century Spain, particularly in provincial towns and rural areas. His "Mercado de Ávila" (Ávila Market) is a prime example, bustling with figures, goods, and the lively interactions of a community. Such works are characterized by their keen observation, rich local color, and an affectionate portrayal of Spanish popular types. He captured the textures of life – the fabrics, the market wares, the expressions of the people – with a sensitivity that brings these scenes to life. These paintings are invaluable historical documents as much as they are artistic achievements, preserving a visual record of a way of life that was gradually changing. His "Recuerdo de Ávila" (Memory of Ávila), dated 1871, further underscores his connection to specific locales and his ability to evoke their unique atmosphere.

Notable Works and Artistic Characteristics

Several works stand out in Lizcano's oeuvre, illustrating his stylistic traits and thematic preoccupations.

"Mercado de Ávila" (Ávila Market) is a quintessential costumbrista piece. It likely depicts a vibrant, crowded market day in the historic Castilian city of Ávila. One can imagine the canvas filled with vendors selling their wares, townspeople and country folk mingling, children playing, and animals perhaps wandering through. Lizcano's skill would lie in orchestrating this complex scene, giving individuality to the figures while creating a cohesive and lively whole. The use of color would be crucial in conveying the atmosphere – the earthy tones of the region, the bright colors of textiles or produce.

"Corrida de toros" (Bullfight Scene) would showcase Lizcano's ability to capture action and drama. Such a painting might focus on a specific moment in the bullfight: the matador's elegant pass, the charge of the bull, or the excitement of the crowd. His Goyaesque leanings might be evident here in the expressive depiction of the figures and the raw energy of the event. The composition would likely be dynamic, drawing the viewer's eye to the central confrontation.

"Recuerdo de Ávila" (Memory of Ávila, 1871) suggests a more personal or evocative take on the city. Unlike a straightforward market scene, a "memory" might be imbued with a certain nostalgia or a focus on a particularly characteristic aspect of Ávila, perhaps its famous medieval walls or a quiet, atmospheric street. The date 1871 places it relatively early in his mature career, indicating his long-standing interest in depicting specific Spanish locales.

Beyond these, Lizcano was also a prolific illustrator, notably providing illustrations for editions of Cervantes' Don Quixote. This endeavor required a deep understanding of the literary source and the ability to translate its iconic characters and scenes into visual form. Illustrating Don Quixote was a prestigious task undertaken by many Spanish artists, and Lizcano's contributions would have further solidified his reputation.

His overall style is marked by competent drawing, a rich and often vibrant palette, and a brushwork that could be both detailed and expressive. He managed to navigate between the polished finish often favored by academic circles and a more painterly approach that lent vitality to his scenes of popular life.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Career

Ángel Lizcano y Monedero actively participated in the artistic life of his time, regularly submitting works to the National Exhibitions of Fine Arts (Exposiciones Nacionales de Bellas Artes). These exhibitions were crucial for an artist's career, providing visibility, critical assessment, and the opportunity for official purchases and medals. Lizcano received several awards in these exhibitions, a testament to the quality of his work and its acceptance by the artistic establishment of the day.

His paintings found their way into various collections, and his reputation extended beyond the capital. The fact that a museum in his birthplace, Alcázar de San Juan, dedicates space to his work underscores his importance as a local artistic hero and his contribution to the region's cultural heritage. Such local recognition is often a strong indicator of an artist's lasting impact on their community.

As he continued to paint into the early 20th century, the Spanish art scene was evolving rapidly. Artists like Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, with his luminous beach scenes, and Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta, with his more somber and dramatic portrayals of Spanish identity, were gaining international fame, representing different facets of modern Spanish painting. While Lizcano may not have embraced the more radical stylistic innovations of the avant-garde, he remained a respected figure, continuing to produce work that resonated with his established themes. The influence of landscape painters like Carlos de Haes, who introduced a more realistic approach to landscape painting in Spain, might also be seen in the settings of Lizcano's outdoor scenes.

The Spanish Art Scene in Lizcano's Time

To fully appreciate Lizcano's contributions, it's important to understand the context of the Spanish art world during his lifetime. The 19th century began with the towering figure of Goya, whose influence would echo through generations. The middle of the century was dominated by Romanticism (with figures like Jenaro Pérez Villaamil known for his romantic landscapes) and the rise of historical painting, heavily promoted by the academies.

Costumbrismo, as practiced by Lizcano, José Elbo, and others, served as a vital counterpoint, focusing on contemporary life and local identity. It was a genre that found favor with the burgeoning middle class and also appealed to foreign visitors fascinated by Spain's "exotic" culture.

The latter part of the 19th century saw the impact of Realism, and then the arrival of new ideas from Paris, including Impressionism. While Spain's engagement with Impressionism was perhaps more cautious than in France, artists like Darío de Regoyos began to explore its possibilities. Lizcano operated within this complex and evolving artistic environment, carving out a niche that honored tradition while also capturing the spirit of his time. He was part of a generation that, in many ways, helped to define a visual Spanish identity before the more radical breaks of the 20th-century avant-garde. Other notable contemporaries whose work formed part of this rich artistic tapestry include Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta, known for his elegant portraits and genre scenes, and José Villegas Cordero, who achieved international success with his historical and orientalist paintings.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Ángel Lizcano y Monedero passed away in Leganés in 1929. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his contemporaries like Sorolla or Fortuny, his contribution to Spanish art is undeniable. He was a skilled and dedicated chronicler of Spanish life, history, and culture. His works continue to be valued for their artistic merit, their historical insight, and their affectionate portrayal of Spain and its people.

The decision to erect a bronze statue in his honor in 2006, created by the sculptor Isabel Pérez Gago and placed in the "Parque de Alcázar de San Juan" in Leganés, is a significant posthumous tribute. It indicates a renewed appreciation for his work and a desire to commemorate his artistic legacy, connecting his birthplace with the place where he spent his later years. Such memorials play an important role in keeping an artist's memory alive for future generations.

His paintings are held in various public and private collections, and they occasionally appear at auctions, demonstrating continued interest from collectors and art enthusiasts. For art historians, Lizcano's work provides valuable insights into the artistic trends, social customs, and cultural preoccupations of 19th-century Spain.

Conclusion

Ángel Lizcano y Monedero was an artist deeply rooted in the Spanish tradition, yet responsive to the artistic currents of his time. He skillfully navigated the demands of historical painting, captured the thrilling spectacle of the bullfight, and, perhaps most memorably, depicted the everyday life of his compatriots with warmth and authenticity. His legacy is that of a versatile and observant painter who contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of Spanish art. Through his canvases, we gain a vivid glimpse into the Spain of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a world he documented with both artistic skill and profound affection. His work remains a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the soul of a nation.