Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta stands as a monumental figure in Spanish art, a painter whose canvases captured the very essence of his nation's soul at the turn of the 20th century. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of Spanish masters yet touched by contemporary European currents, offered a powerful and often stark vision of Spain, its people, and its enduring customs. This exploration delves into the life, art, and legacy of a man who dedicated his career to portraying the multifaceted identity of his homeland.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in the Basque Country

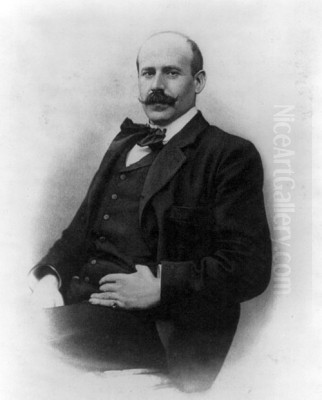

Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta was born on July 26, 1870, in the small Basque town of Eibar, Gipuzkoa, a region renowned for its strong cultural identity and artisanal traditions. His birthplace was situated near the historic Loyola Sanctuary, a significant spiritual and cultural landmark. The Zuloaga family was already distinguished in the arts and crafts, particularly in metalwork and damascening, a highly skilled technique of inlaying different metals into one another. This familial environment, steeped in craftsmanship and artistic endeavor, undoubtedly shaped young Ignacio's earliest sensibilities.

His father, Plácido Zuloaga, was a celebrated damascene artist and metalworker of international repute. The family workshop, a hub of creative activity, served as Ignacio's first school. Here, amidst the clang of hammers and the intricate designs taking shape, he received his initial instruction in drawing and engraving. This early exposure to the discipline of craft, the meticulous attention to detail, and the tangible creation of beautiful objects would lay a foundational understanding of form and material that would later inform his painting.

Despite his father's initial hopes that Ignacio might pursue a more conventional career in commerce or engineering, the young man's passion for painting proved irresistible. The allure of the canvas and the expressive power of color and line held a stronger sway over his imagination. Recognizing his son's burgeoning talent and unwavering dedication, Plácido eventually supported his artistic aspirations.

A pivotal moment in Zuloaga's early development came with his exposure to the masterpieces housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid. In 1887, he began his formal studies there, immersing himself in the works of the great Spanish masters. The profound impact of artists like Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, and El Greco cannot be overstated. Their dramatic use of light and shadow, their psychological depth in portraiture, and their unflinching depiction of Spanish life resonated deeply with Zuloaga, planting the seeds for his own artistic vision.

The Parisian Crucible: Influences and Early Success

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Zuloaga, like many aspiring artists of his generation, was drawn to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the late 19th century. He arrived in Montmartre in 1889, a vibrant bohemian quarter teeming with artists, writers, and intellectuals. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to a whirlwind of new ideas and artistic movements.

In Paris, Zuloaga encountered Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He formed connections with artists who were pushing the boundaries of traditional art. Among his acquaintances were figures such as Paul Gauguin, whose bold use of color and exploration of primitive themes were revolutionizing painting, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose incisive portrayals of Parisian nightlife captured a specific modern sensibility. He also associated with Catalan modernista painters like Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas, who were similarly exploring new artistic languages while often retaining a connection to their Spanish roots. Edgar Degas, with his masterful drawing and unconventional compositions, was another significant presence in the Parisian art scene whose work Zuloaga would have known.

Zuloaga's artistic training continued in Paris, where he studied with Henri Gervex, a painter known for his large-scale history paintings and society portraits. While he absorbed the lessons of these contemporary movements, Zuloaga's artistic compass remained intrinsically linked to the Spanish tradition. He did not fully embrace Impressionism's dissolution of form or its primary focus on fleeting atmospheric effects. Instead, he selectively incorporated elements that resonated with his own developing style, particularly a brighter palette and a more direct approach to capturing reality.

His talent soon gained recognition. In 1890, Zuloaga achieved his first significant success when one of his paintings was accepted and exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon. This early validation on such an important stage was a considerable encouragement for the young artist. His works from this period often reflected the Parisian environment, but a gradual shift was already underway.

A Return to Spanish Soil: Forging a National Art

Despite his experiences and successes in Paris, Zuloaga felt an increasingly strong pull towards his homeland. The artistic currents of Paris were stimulating, but his deepest artistic inspiration lay in the landscapes, people, and culture of Spain. He began to spend more time in Spain, particularly in Andalusia and Castile, regions that offered a rich tapestry of subjects that resonated with his artistic vision.

This period marked a decisive turn in Zuloaga's art. He consciously moved away from the more cosmopolitan themes he might have explored in Paris and began to focus intensely on what he perceived as the authentic character of Spain. His subject matter became increasingly nationalistic, centering on figures and scenes that embodied Spanish tradition and identity. Bullfighters (toreros), flamenco dancers, gypsies, rugged peasants, and devout religious figures began to populate his canvases.

His style also consolidated during this time. While retaining some of the lessons learned in Paris regarding color and light, Zuloaga's work became more grounded in a powerful, often somber, realism. He drew heavily on the legacy of the Spanish Golden Age painters, particularly the dramatic intensity of El Greco, the profound humanism of Velázquez, and the raw expressiveness of Goya. His figures possessed a sculptural solidity and a psychological weight that set them apart from the lighter, more ephemeral qualities of Impressionism.

Zuloaga's commitment to depicting "la España negra" (Black Spain) – a term often associated with a more tragic, austere, and traditional vision of the country, in contrast to a sunnier, more romanticized image – became a hallmark of his work. He sought to capture the enduring, sometimes harsh, realities of Spanish life, its deep-rooted traditions, and the stoic character of its people.

Key Thematic Concerns in Zuloaga's Oeuvre

Zuloaga's body of work is characterized by several recurring themes that reflect his profound engagement with Spanish culture and identity.

The World of Bullfighting: The corrida, or bullfight, was a central motif in Zuloaga's art. He was not merely an observer but a passionate aficionado, and he even participated as an amateur bullfighter. His paintings of toreros, such as the celebrated Toreros de la Plebe (Village Bullfighters), go beyond mere depiction of the spectacle. They explore the dignity, courage, and tragic grandeur associated with the bullfight, often portraying the matadors with a heroic, almost mythic, quality. He captured the vibrant costumes, the tense atmosphere of the arena, and the intense personalities of the bullfighters themselves.

Gypsy Culture and Flamenco: Zuloaga was deeply fascinated by Gypsy (Gitano) culture and the art of flamenco. He spent considerable time with Gypsy communities, learning their language, Caló, and immersing himself in their way of life. His portraits of Gypsy women, often adorned in traditional attire, are among his most striking works. Paintings like Gitana del Palacio (Gypsy Woman of the Palace) convey a sense of pride, resilience, and untamed spirit. He admired their perceived freedom and their passionate expression through music and dance, elements he sought to translate onto canvas.

Portraits of Spanish Types: Zuloaga was a master portraitist. He painted a wide array of Spanish "types," from rugged Castilian peasants and devout old women to local notables and members of his own family. These portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and their ability to convey the sitter's character and social standing. Works like Sprightly Old Man or portraits of women from various regions of Spain reveal his keen observation and his empathy for his subjects. He often placed his figures against stark, evocative landscapes that seemed to echo their inner lives.

Landscapes of Castile and the Basque Country: The Spanish landscape, particularly the arid, expansive plains of Castile and the rugged terrain of his native Basque Country, served as a powerful backdrop and often a subject in its own right in Zuloaga's paintings. His landscapes are rarely picturesque in the conventional sense. Instead, they are imbued with a sense of history, austerity, and timelessness. Towns like Sepúlveda and Segovia, with their ancient architecture and dramatic settings, feature prominently, often rendered in a palette of earth tones, grays, and deep blues that emphasize their stark beauty. The painting Segovia is a prime example of his ability to capture the spirit of a place.

Religious Themes and Traditions: While not exclusively a religious painter, Zuloaga depicted scenes related to Spanish religious traditions and popular piety. Works like Cristo de la Sangre (also known as The Flagellants or Hermandad del Cristo Crucificado) portray the intense, sometimes brutal, devotion characteristic of certain Spanish religious practices, such as Holy Week processions. These paintings, with their dramatic lighting and somber mood, recall the religious art of El Greco and Goya, reflecting the enduring power of faith in Spanish culture.

Artistic Style and Technique: A Synthesis of Tradition and Modernity

Ignacio Zuloaga's artistic style is a distinctive fusion of Spanish artistic heritage and certain modern sensibilities. His approach was fundamentally realist, but it was a realism infused with a dramatic, almost theatrical, quality.

Color Palette and Light: Zuloaga is known for his characteristic color palette, which often favored somber earth tones, deep grays, blacks, and muted blues. This palette contributed to the gravitas and austerity of many of his scenes, particularly those depicting the Castilian landscape or figures of stoic peasants. However, he was also capable of using color with great vibrancy and impact, especially in the depiction of traditional costumes, such as the brilliant reds and yellows of a bullfighter's "suit of lights" or the rich hues of a flamenco dancer's dress. His use of light was often dramatic, employing strong chiaroscuro reminiscent of the Spanish Baroque masters to model his figures and create a sense of volume and intensity.

Influence of Spanish Masters: The profound influence of earlier Spanish painters is a cornerstone of Zuloaga's art. From El Greco, he absorbed a sense of spiritual intensity, elongated figures, and dramatic compositions. Velázquez provided a model for profound psychological portraiture and masterful handling of paint. Goya's influence can be seen in Zuloaga's unflinching depiction of Spanish life, his interest in popular types, and his occasional exploration of darker, more unsettling themes. He collected works by these masters, notably El Greco, whose art was undergoing a significant reappraisal during Zuloaga's lifetime.

Figurative Strength and Composition: Zuloaga's figures possess a strong, sculptural presence. He emphasized their physicality and their expressive potential through pose and gesture. His compositions are often carefully constructed, with figures placed prominently within the pictorial space, sometimes set against expansive, atmospheric landscapes that add to the overall mood and narrative of the painting. There is a deliberate, almost monumental, quality to many of his works.

Rejection of Avant-Garde Extremes: While Zuloaga lived through a period of radical artistic experimentation, including the rise of Fauvism, Cubism (pioneered by fellow Spaniards Pablo Picasso and Juan Gris), and Surrealism (championed by Salvador Dalí), he remained largely aloof from these avant-garde movements. His artistic path was more aligned with a modern interpretation of the realist tradition. He sought to create an art that was recognizably Spanish and that spoke to a broad audience, rather than engaging in the formal deconstructions of the avant-garde. This stance sometimes led to him being perceived as conservative by proponents of more radical art forms.

Notable Works: Icons of Spanish Identity

Several of Zuloaga's paintings have become iconic representations of his artistic vision and his portrayal of Spain.

Merceditas: This portrait is a tender and insightful depiction, likely of a young woman, showcasing Zuloaga's skill in capturing individual personality with sensitivity. The soft, harmonious colors and the vivid rendering of the figure are characteristic of his portraiture.

Las Hechiceras de San Millán (The Witches of San Millán): This work delves into the realm of Spanish folklore and superstition, a theme also explored by Goya. It depicts a group of women in a rugged landscape, hinting at ancient beliefs and the mystical undercurrents of rural Spain.

La Mujer de Madrid (Woman from Madrid): This painting likely captures a specific type or character associated with the Spanish capital, rendered with Zuloaga's characteristic strength and attention to costume and demeanor.

Condesa de Noailles (Countess of Noailles): This portrait of the French writer and socialite Anna de Noailles demonstrates Zuloaga's ability to move within international aristocratic circles and to capture the elegance and intellect of his sitters. It highlights his versatility as a portraitist, capable of depicting both humble peasants and sophisticated members of high society.

Lucienne Bréval as Carmen (1908): This dynamic painting depicts the famous opera singer Lucienne Bréval in the title role of Bizet's opera Carmen. Zuloaga masterfully captured the drama and passion of the character, leveraging the Parisian fascination with Spanish themes. The work was praised for its theatricality and vibrant portrayal.

The Penitents (Cristo de la Sangre, 1908): This powerful and somber work shows a procession of hooded penitents during Holy Week, a scene of intense religious fervor. The dramatic lighting and the stark, almost dreamlike atmosphere evoke the deep-rooted and often austere religious traditions of Spain.

These works, among many others, solidified Zuloaga's reputation as a leading painter of Spanish life and character.

Relationships, Collaborations, and Personality

Ignacio Zuloaga was a well-connected figure in the artistic and cultural circles of his time, both in Spain and internationally.

His early artistic education was shaped by his father, Plácido Zuloaga, and he also studied under the Basque painter José Echena (also known as José Echenagusia Errazquin), who was known for his historical and genre scenes. In Paris, his interactions with artists like Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Rusiñol were formative. He also maintained a lifelong friendship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin, whose powerful, expressive figures Zuloaga greatly admired.

A significant artistic collaboration was with the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla. Together, they worked on the puppet opera El retablo de maese Pedro (Master Peter's Puppet Show), for which Zuloaga designed the sets and puppets. This project, first performed in 1923, was a celebrated fusion of music and visual art, drawing inspiration from Cervantes' Don Quixote.

Zuloaga was known for his distinctive personality. He had a deep affection for Gypsy culture and was reportedly fluent in Caló. His admiration for the freedom and passion of the Gypsies was a genuine aspect of his character. He was also an avid bullfighting enthusiast. Anecdotes describe his excitement when witnessing a skilled torero. Certain personal habits, like frequently carrying a cane (janguillo) and wearing a white scarf (guerniza), added to his unique persona. Despite the often somber or dramatic nature of his paintings, Zuloaga himself was described as having an optimistic outlook on life. He was a social individual, cultivating friendships with writers, musicians, and fellow artists, including the composer Maurice Ravel.

International Recognition and Exhibitions

Zuloaga's work gained significant international acclaim during his lifetime. He exhibited widely across Europe and the Americas, and his paintings were acquired by major museums and private collectors.

His success at the Paris Salon was an early indicator of his international appeal. The French government's purchase of his painting Daniel Zuloaga and His Daughters (a portrait of his uncle, a renowned ceramicist, and his cousins) was a significant honor. He held successful exhibitions in cities such as Brussels, Berlin, Dresden, Rome, London, New York, Boston, and Buenos Aires.

In the United States, Zuloaga's exhibitions in the early 20th century were particularly impactful, introducing American audiences to his powerful vision of Spain. Critics and the public were captivated by the exoticism and raw energy of his subjects, as well as by the technical mastery of his painting. His work offered a striking contrast to the more genteel academic art or the increasingly abstract tendencies of the European avant-garde. He was often hailed as the "Soul of Spain," a painter who captured the authentic spirit of his nation.

This international recognition solidified his status as one of Spain's foremost modern painters, alongside contemporaries like Joaquín Sorolla, whose sun-drenched depictions of Spanish life offered a contrasting, though equally popular, vision of the country.

The Later Years and the Franco Era

Zuloaga continued to paint prolifically throughout his life. His artistic vision remained consistent, focused on the themes and subjects that had defined his career. He established a home and studio in Zumaia, on the Basque coast, where a museum dedicated to his work and collections now stands (the Zuloaga Museum - Espacio Cultural Ignacio Zuloaga).

The period of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and the subsequent Franco dictatorship was a complex time for Spanish artists. Zuloaga's work, with its emphasis on traditional Spanish values and national identity, found favor with the Franco regime. He became an important cultural figure during this era, and his art was seen by some as aligning with the regime's nationalistic ideology. This association has been a subject of discussion and varying interpretations by art historians. However, his primary artistic concerns predated the Franco era and were rooted in a long-standing engagement with Spanish culture.

Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta died in his studio in Madrid on October 31, 1945, at the age of 75, leaving behind a vast and influential body of work.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Ignacio Zuloaga's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered as a powerful interpreter of Spanish identity, an artist who, through his vivid portrayals of its people, customs, and landscapes, helped to define a particular vision of Spain for both national and international audiences.

His work represents a significant strand of Spanish modern art that sought to reconcile tradition with a modern sensibility. While not an avant-garde revolutionary in the mold of Picasso or Miró, Zuloaga's contribution lies in his revitalization of the realist tradition and his profound exploration of national character. He demonstrated that figurative painting, rooted in the legacy of the Old Masters, could still possess immense power and relevance in the modern era.

His paintings are housed in major museums around the world, including the Museo del Prado and the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, the Hispanic Society of America in New York, and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. The Zuloaga Museum in Zumaia preserves his studio, personal collections (which included important works by El Greco, Goya, and Zurbarán), and a significant number of his own paintings, offering invaluable insight into his life and art.

Zuloaga's influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Spanish painters who continued to explore themes of national identity and realist representation. His work also contributed to a broader international understanding and appreciation of Spanish culture. While artistic tastes and critical perspectives evolve, Zuloaga's paintings retain their power to evoke the spirit of a particular Spain, a land of stark beauty, profound traditions, and enduring human dignity. He remains a key figure for understanding the complexities of Spanish art and culture in the 20th century.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision of Ignacio Zuloaga

Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta carved a unique and enduring path in the landscape of modern art. Born into a legacy of Basque craftsmanship and nurtured by the grand traditions of Spanish painting, he forged an artistic identity that was both deeply personal and profoundly national. His canvases, populated by bullfighters, gypsies, peasants, and the stark, timeless landscapes of Spain, offer a compelling, if sometimes somber, vision of his homeland.

While his contemporaries in Paris and elsewhere were deconstructing form and challenging the very nature of representation, Zuloaga chose to reinvest in the power of realism, infusing it with a modern psychological depth and a dramatic intensity that was entirely his own. He looked to El Greco, Velázquez, and Goya not as historical relics, but as living sources of inspiration for an art that could speak to the present.

His international acclaim brought Spanish culture to a global audience, and his unwavering commitment to his artistic vision, even when it ran counter to prevailing avant-garde trends, underscores his integrity and self-assurance. Ignacio Zuloaga's legacy is that of an artist who, with consummate skill and profound empathy, painted the soul of Spain, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its power, authenticity, and deep humanism.