Annibale Carracci stands as a colossus in the annals of Italian art history, a pivotal figure whose work forged a crucial link between the waning Mannerist style of the late Renaissance and the burgeoning dynamism of the Baroque era. Born in Bologna on November 3, 1560, and passing away in Rome on July 15, 1609, Annibale, alongside his older brother Agostino Carracci and their cousin Ludovico Carracci, spearheaded an artistic revolution that emphasized a return to naturalism and the classical ideals, profoundly shaping the course of European painting for generations to come.

His career, marked by intense collaboration, groundbreaking innovation, and ultimately personal tragedy, saw him rise from provincial beginnings to become one of the most sought-after artists in Rome. His legacy is cemented not only by his masterpieces, particularly the Farnese Gallery ceiling, but also by the influential academy he co-founded, which became a crucible for nurturing the next wave of Baroque talent.

Bolognese Roots and Early Development

Annibale Carracci's artistic journey began in his native Bologna, a city with a rich, albeit distinct, artistic tradition compared to Florence or Rome. He received his initial training likely within the family circle, learning from his cousin Ludovico. Unlike the highly artificial and stylized conventions of late Mannerism prevalent at the time, the Carracci milieu fostered a different approach. Annibale, in particular, showed an early inclination towards observing the world around him directly.

His early development was significantly shaped by travels and exposure to other artistic centers. Visits to Parma allowed him to absorb the sensuous grace and soft sfumato of Antonio da Correggio, whose influence is palpable in Annibale's handling of light and tender emotion. Equally important were his encounters with the Venetian school during trips to Venice. The rich color, dramatic lighting, and painterly textures of masters like Titian and Paolo Veronese left an indelible mark on his developing style, encouraging a bolder use of color and a more dynamic approach to composition than typical Bolognese practice.

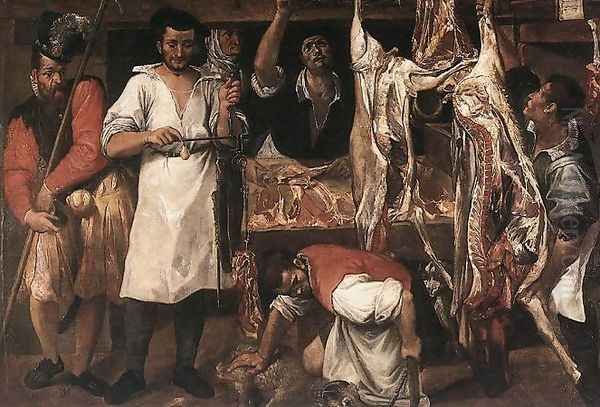

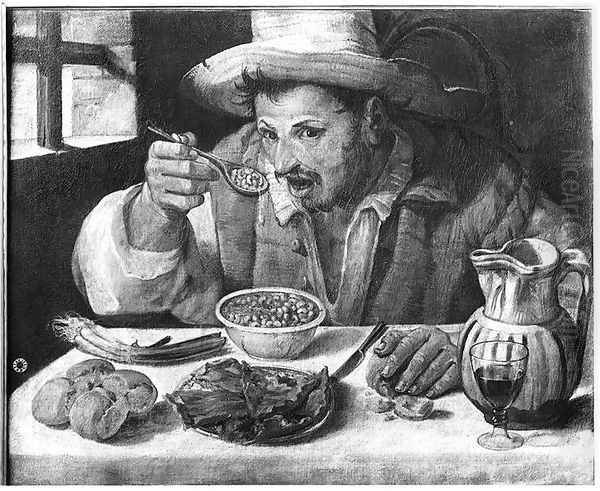

These formative experiences coalesced in his early works produced in Bologna during the 1580s. He demonstrated a remarkable versatility, tackling religious commissions, mythological subjects, and strikingly novel genre scenes. Works like The Butcher's Shop (c. 1582-83) and The Bean Eater (c. 1584-85) were revolutionary for their time, depicting scenes of everyday life with an unvarnished realism and dignity that broke sharply from Mannerist elegance. These paintings showcased his keen observational skills and his interest in capturing the textures and activities of ordinary people, rendered with earthy tones and robust forms.

Simultaneously, he undertook significant religious commissions. The altarpiece The Baptism of Christ (1585), painted for the Church of San Gregorio in Bologna, reveals his growing synthesis of influences. It combines Correggio's softness and Venetian color with a clear, stable compositional structure derived from High Renaissance masters like Raphael, demonstrating his ambition to fuse the best elements of different traditions.

The Carracci Academy: A Crucible of Reform

A cornerstone of the Carracci legacy was the founding of their academy in Bologna around 1582. Initially known as the Accademia dei Desiderosi (Academy of the Desirous) and later renamed the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of the Progressives or Those Setting Out), it represented a conscious effort to reform painting. The Carracci sought to move beyond what they perceived as the overly intellectualized and artificial nature of Mannerism, advocating instead for a return to the principles of High Renaissance classicism combined with a rigorous study of nature.

The academy was a collaborative venture, with Ludovico providing guidance, Agostino contributing his intellectual and theoretical knowledge (he was also a renowned engraver), and Annibale serving as the primary driving force through his sheer artistic talent and innovative spirit. Their teaching methods were revolutionary for the time. They emphasized drawing from life (disegno), anatomical studies, the study of classical sculpture, and drawing inspiration directly from nature and everyday reality, rather than solely imitating other masters.

This educational program aimed to equip artists with a comprehensive understanding of form, structure, light, and expression. The academy quickly became a vital center for artistic training in Bologna, attracting talented students who would go on to become major figures of the next generation. Among the most notable pupils were Guido Reni, Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri), and Francesco Albani, all of whom absorbed the Carracci principles and helped disseminate their style throughout Italy.

The collaborative spirit extended beyond teaching to joint artistic projects. The Carracci family undertook several major fresco cycles in Bolognese palaces during the 1580s and early 1590s. Their work in the Palazzo Fava (decorations depicting the stories of Jason and Medea, c. 1583-84) and later in the Palazzo Magnani (frescoes illustrating the founding of Rome, c. 1590-92) showcased their collective ability to create complex, dynamic narratives that blended classical themes with naturalistic observation and vibrant energy. These projects solidified their reputation and demonstrated the power of their reformed style.

The Call to Rome: The Farnese Commission

Annibale's rising fame and the innovative power of his art eventually attracted attention from the highest echelons of patronage. In 1595, he received the prestigious invitation to move to Rome under the patronage of Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, one of the wealthiest and most influential figures in the city. This move marked a turning point in Annibale's career, placing him at the very center of the Italian art world and providing him with the opportunity to create his most enduring masterpieces.

His first major task for Cardinal Farnese was the decoration of a smaller room in the Palazzo Farnese, known as the Camerino. Here, between 1595 and 1597, Annibale painted mythological scenes centered around the theme of virtue, most notably The Choice of Hercules. This work already displayed his mature Roman style: a powerful synthesis of classical forms, inspired by ancient sculpture and the works of Raphael and Michelangelo, combined with his characteristic naturalism and rich coloring.

The success of the Camerino project led to the commission that would define Annibale's career: the decoration of the barrel-vaulted ceiling of the grand gallery on the main floor of the Palazzo Farnese. Working primarily between 1597 and 1601 (with some later additions), Annibale created The Loves of the Gods, a complex and dazzling fresco cycle that stands as one of the seminal works of Baroque art.

Masterpiece: The Farnese Gallery Ceiling

The Loves of the Gods is an exuberant celebration of mythological love, depicting various scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses and other classical sources. Annibale employed an ingenious compositional device known as quadro riportato ("transported picture"), where individual scenes are painted as if they were framed easel paintings set into the architecture of the ceiling. These framed scenes are surrounded by illusionistic elements: painted stucco figures (ignudi inspired by Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling), bronze medallions, garlands, and putti, all creating a vibrant interplay between different levels of reality.

The central scene, The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, is a dynamic and joyous procession filled with mythological figures rendered with remarkable energy and naturalism. Throughout the ceiling, Annibale demonstrates his mastery of drawing the human figure in complex poses, his sophisticated understanding of classical antiquity, his brilliant use of light and color derived from his Venetian studies, and his ability to convey a wide range of emotions, from playful sensuality to divine power.

The Farnese ceiling was immediately hailed as a masterpiece. It represented a powerful alternative to the stark drama of Caravaggio, another artistic giant working in Rome at the same time. While Caravaggio emphasized intense realism and dramatic chiaroscuro in religious scenes often set in contemporary squalor, Annibale offered a vision rooted in classical harmony, idealized beauty, and learned allegory, yet infused with a palpable sense of life and naturalism. The ceiling became a "school" for subsequent generations of artists, including Peter Paul Rubens, Nicolas Poussin, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who studied it intently.

Agostino Carracci initially assisted Annibale on the project but left Rome around 1600, reportedly due to disagreements with his brother. Annibale, possibly with assistance from pupils like Domenichino for some minor parts, brought the monumental work to completion.

Artistic Style: Synthesis and Innovation

Annibale Carracci's mature style is characterized by its masterful synthesis of diverse artistic traditions. He successfully merged the strengths of North Italian painting – the colorito (emphasis on color and painterly effects) of Venice (Titian, Veronese) and the sfumato and grace of Parma (Correggio) – with the Central Italian tradition of disegno (emphasis on drawing and design) exemplified by Florentine and Roman masters like Raphael and Michelangelo.

His commitment to naturalism remained a constant thread. Even when depicting mythological or religious subjects, his figures possess a physical presence and psychological believability derived from careful observation of life. This naturalism extended to landscape painting, where Annibale made significant contributions. Works like the Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (c. 1604) treat the landscape not merely as a backdrop but as a subject imbued with mood and atmosphere, paving the way for the ideal landscapes of later artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Classicism was equally fundamental. Annibale deeply admired classical antiquity and the High Renaissance. He studied ancient sculptures and architectural forms, incorporating their balance, harmony, and idealized beauty into his own compositions. However, his classicism was never cold or purely imitative; it was always animated by his naturalistic impulse and emotional sensitivity.

Drawing was central to his creative process. Annibale was a prolific and brilliant draftsman, producing countless preparatory sketches from life, studies of anatomy, and compositional designs. His drawings reveal his method of exploring poses, expressions, and light effects before committing them to paint. This rigorous preparatory process underpinned the apparent effortlessness and vitality of his finished works.

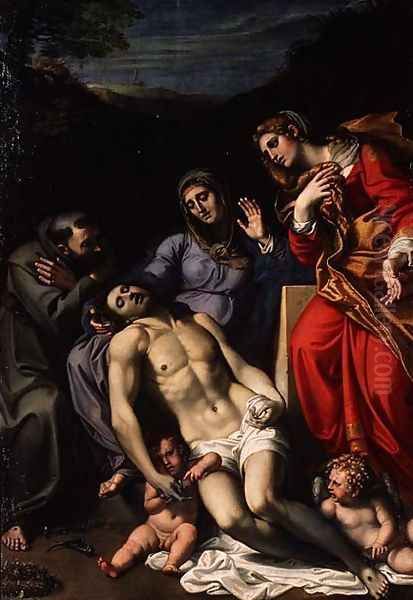

His use of color was rich and varied, often employing vibrant hues reminiscent of Venetian painting, but always controlled within a clear compositional structure. His handling of light, while less dramatically contrasted than Caravaggio's tenebrism, was sophisticated, used to model form, create atmosphere, and direct the viewer's eye. In religious works like his poignant Pietà (c. 1600), he demonstrated a profound capacity for conveying deep emotion through gesture, expression, and the interplay of light and shadow.

Contemporaries and Influence

Annibale Carracci worked during a period of intense artistic ferment in Rome, interacting with and reacting to other major talents. His most significant contemporary was Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. They represented the two dominant poles of early Baroque painting in Rome: Carracci's classically inspired naturalism versus Caravaggio's dramatic, often brutal, realism. While sometimes positioned as rivals, their relationship was complex; they likely respected each other's distinct talents. A famous juxtaposition occurred in the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, where Annibale's altarpiece The Assumption of the Virgin (1600-1601) hangs between two powerful canvases by Caravaggio, The Crucifixion of St. Peter and The Conversion of St. Paul. The contrast highlights their different artistic visions.

Annibale's influence radiated primarily through the Carracci Academy and the pupils he trained. Guido Reni, Domenichino, Francesco Albani, and Giovanni Lanfranco all emerged from his circle, becoming leading painters of the next generation. They adapted and developed aspects of his style – Reni pursuing a refined classicism, Domenichino known for his compositional clarity and emotional restraint, Albani specializing in charming mythological landscapes, and Lanfranco exploring more dynamic, High Baroque illusionism inspired partly by Correggio, whom Annibale had also admired.

Beyond his direct pupils, Annibale's work profoundly impacted major European artists. Peter Paul Rubens, during his stay in Italy, studied Carracci's work closely, particularly the Farnese ceiling, which influenced his own exuberant Baroque style. Nicolas Poussin, the great French classicist painter working in Rome, drew heavily on Annibale's synthesis of classicism and naturalism. Even the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the defining genius of Roman Baroque sculpture, found inspiration in the dynamic figures and emotional intensity of Carracci's paintings.

Final Years: Melancholy and Legacy

Despite the triumph of the Farnese Gallery, Annibale's later years were clouded by disappointment and ill health. There is strong evidence suggesting he felt poorly compensated by Cardinal Farnese for his monumental efforts on the ceiling. This perceived lack of recognition, coupled perhaps with the immense physical and mental strain of the project, seems to have contributed to a severe bout of depression or melancholy ("melancholia") that afflicted him from around 1605 onwards.

His condition significantly hampered his ability to work. His output slowed, and he increasingly relied on his workshop, particularly Domenichino, to assist in completing commissions. Anecdotes from the period describe him as withdrawn and despondent. He sought changes of scenery, but his health continued to decline.

Annibale Carracci died in Rome on July 15, 1609, at the relatively young age of 48. In a testament to the high esteem in which he was held, despite his recent struggles, he was buried according to his wishes in the Pantheon, near the tomb of the artist he revered perhaps above all others, Raphael.

His death did not diminish his influence. The artistic principles he championed – the synthesis of naturalism and classicism, the importance of life drawing, the revival of monumental fresco painting – became foundational tenets of academic art theory for centuries. His Farnese ceiling remained a touchstone, a model for ambitious decorative schemes across Europe.

Evolving Reputation

Annibale Carracci's reputation has undergone significant shifts over time. In the 17th century, he was widely celebrated, particularly by theorists like Giovanni Pietro Bellori, who saw him as the savior of painting, rescuing it from Mannerist decline and restoring the classical tradition of Raphael. His style formed the basis of the dominant classicizing trend in Baroque art.

However, during the 18th and especially the 19th centuries, his fame waned. Neoclassical critics like Johann Joachim Winckelmann found his work insufficiently pure compared to ancient Greek art. Later, Romantic critics, most famously John Ruskin, dismissed him and the Bolognese school as "eclectic," accusing them of lacking originality and deep feeling by merely combining elements from previous masters.

The 20th century witnessed a major reassessment of Annibale Carracci and the Baroque era. Art historians began to appreciate the true innovation and power of his work, recognizing his crucial role in forging the Baroque style. His synthesis was re-evaluated not as mere eclecticism but as a creative and dynamic fusion that revitalized painting. His naturalism, his psychological depth, his technical brilliance, and the sheer beauty of works like the Farnese ceiling were once again acknowledged. Contemporary scholarship continues to explore various facets of his art, including his drawings, his landscape painting, and the complex interplay between his personal life and his artistic production.

Conclusion

Annibale Carracci remains a figure of paramount importance in the history of Western art. He was more than just a painter; he was a reformer, an educator, and a visionary who navigated the complex transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque. Through his commitment to drawing from life, his deep engagement with classical antiquity and the masters of the High Renaissance, and his own innate genius for composition, color, and expression, he forged a powerful and influential new direction for painting. His masterpiece, the Farnese Gallery ceiling, stands as a testament to his artistic ambition and skill, while the academy he co-founded shaped the education of artists for generations. Though his later life was marked by sadness, Annibale Carracci's legacy endures in the countless artists he influenced and in the enduring power and beauty of his art.