Antonio Molinari (1655-1704) stands as a significant figure in the Venetian school of painting during the vibrant late Baroque period. His career, though relatively short, marked a pivotal transition in Venetian art, moving from the dramatic tenebrism that characterized much of the 17th century towards a lighter, more elegant style that would blossom in the 18th century with artists like Giambattista Tiepolo. Molinari's work, distinguished by its rich coloration, dynamic compositions, and sensuous figures, earned him considerable acclaim during his lifetime and secured his place in the annals of art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Venice

Born in Venice in 1655, Antonio Molinari was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His father, Giovanni Molinari, was also a painter, though less renowned. This familial connection likely provided Antonio with his initial exposure to the craft. However, his formal training came under the tutelage of Antonio Zanchi (1631-1722), a prominent Venetian painter known for his dramatic, often dark and intense, large-scale canvases. Zanchi was a leading exponent of the "tenebrosi," a group of artists who embraced strong chiaroscuro and theatricality, drawing inspiration from Caravaggio and his followers, as well as from the robust naturalism of Neapolitan painters like Luca Giordano.

Under Zanchi, Molinari would have absorbed the prevailing taste for powerful narratives, often depicting scenes of martyrdom, battles, or dramatic biblical events. Zanchi's style was characterized by vigorous brushwork, crowded compositions, and a somber palette, emphasizing the emotional intensity of his subjects. This early training provided Molinari with a solid foundation in figure drawing, compositional arrangement, and the dramatic use of light and shadow, elements that would remain present, albeit transformed, throughout his career.

The artistic milieu of late 17th-century Venice was a complex tapestry. While the towering legacies of Renaissance masters like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto still loomed large, contemporary painters were forging new paths. Besides Zanchi, other notable figures included Pietro Liberi, known for his more sensual and decorative style, and the German-born Carl Loth (Giovanni Carlo Loth), whose work also featured dramatic intensity and muscular figures. The influence of Neapolitan art, particularly the dynamic and colorful compositions of Luca Giordano, who made visits to Venice, was also beginning to permeate the local scene, offering an alternative to the more austere tenebrism.

Evolution of Style: From Tenebrism to Luminous Elegance

While Molinari's earliest works understandably reflect the darker, more dramatic manner of his master, Antonio Zanchi, he gradually began to forge his own distinct artistic identity. By the 1680s, a noticeable shift occurred in his painting. He started to move away from the heavy shadows and somber tones of his initial phase, developing a style that was brighter, more colorful, and imbued with a greater sense of elegance and refinement. This evolution was likely influenced by several factors, including a broader exposure to different artistic currents and perhaps a personal inclination towards a more sensuous and decorative aesthetic.

His palette became richer and more varied, incorporating luminous blues, warm reds, and golden yellows. While he retained a strong sense of drama in his compositions, the theatricality became less about stark contrasts of light and dark (tenebrism) and more about dynamic movement, graceful figural arrangements, and a harmonious interplay of colors. Molinari's figures, often characterized by their soft flesh tones and elegant, sometimes slightly elongated, forms, exuded a sensuality that distinguished his work from the more rugged naturalism of some of his contemporaries.

The influence of Neapolitan painters, particularly Luca Giordano, can be discerned in the increased dynamism and fluidity of Molinari's compositions. Giordano's "fa presto" (paint quickly) approach and his vibrant, light-filled canvases offered a compelling alternative to the more traditional Venetian methods. Molinari managed to synthesize these influences with the inherent Venetian love for rich color and painterly texture, creating a style that was both innovative and deeply rooted in local tradition. His compositions often featured complex groupings of figures, arranged in dynamic, swirling patterns that guided the viewer's eye through the narrative.

Major Themes and Prominent Commissions

Antonio Molinari's oeuvre primarily consisted of historical, religious, and mythological subjects, catering to the demands of both ecclesiastical and private patrons. Venice, with its numerous churches, confraternities (scuole), and wealthy patrician families, provided ample opportunities for artists like Molinari to secure prestigious commissions. He produced a significant number of large-scale altarpieces and narrative canvases for religious institutions, as well as smaller paintings for private collectors.

His religious paintings often depicted dramatic scenes from the Old and New Testaments. These works showcased his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and to convey a wide range of human emotions. Subjects such as the stories of Moses, David, or episodes from the life of Christ and the saints were common. In these paintings, Molinari demonstrated a keen understanding of biblical narratives, translating them into visually compelling images that were both didactic and aesthetically pleasing.

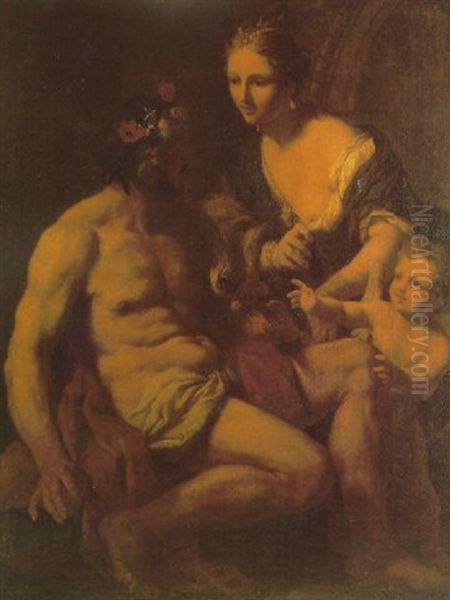

Mythological themes, drawn from classical antiquity, also featured prominently in his work. Tales of gods and goddesses, heroes, and nymphs provided Molinari with opportunities to explore the beauty of the human form and to create compositions filled with sensuousness and dynamism. These paintings were particularly popular with private patrons who appreciated their erudite subject matter and decorative qualities. His treatment of these themes often emphasized the dramatic or emotional aspects of the stories, rendered with his characteristic rich color and elegant figural style.

Key Works and Artistic Achievements

Several key works illustrate Antonio Molinari's artistic prowess and stylistic development. Among his most celebrated paintings is "The Adoration of the Golden Calf" (c. 1690s, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg). This large canvas is a masterful example of his mature style, showcasing a complex, dynamic composition filled with numerous figures, vibrant colors, and a dramatic interplay of light and shadow that, while present, is softer and more diffused than in his earlier tenebrist phase. The figures are rendered with a characteristic grace and sensuality, and the overall effect is one of opulent theatricality.

Another significant work is "The Feeding of the Five Thousand" (c. 1690, San Pantalon, Venice), which demonstrates his skill in organizing a vast narrative scene with clarity and visual impact. The painting is notable for its rich palette and the lively, expressive gestures of the figures. His "History of Joshua" series, including works for the Corpus Domini in Venice, further cemented his reputation. For instance, a painting often cited, sometimes as "Joshua Halting the Sun" or similar episodes from the Book of Joshua, highlights his ability to convey epic narratives with dramatic force and compositional ingenuity.

Molinari also excelled in depicting more intimate mythological scenes, such as "Bacchus and Ariadne" (private collection) or "Susanna and the Elders." These works often feature his signature elegant figures, sensuous flesh tones, and a harmonious balance of color and light. His ability to capture tender or dramatic moments from classical mythology contributed to his popularity among collectors. For example, "The Rape of the Sabines" (Ca' Rezzonico, Venice) is a dynamic and tumultuous composition, showcasing his skill in rendering movement and intense emotion, yet still imbued with a certain grace.

His works are found in prestigious collections, including the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, and various churches and museums throughout Venice and Italy. Critics generally praise Molinari for his excellent design, rich coloration, and expressive power, although some note an occasional unevenness in the quality of his output, which is not uncommon for prolific artists of the period.

Molinari as a Draughtsman

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Antonio Molinari was also a highly skilled draughtsman. A considerable number of his preparatory drawings have survived, offering valuable insights into his creative process. These drawings, typically executed in chalk or pen and ink with wash, reveal his method of working out complex compositions, studying individual figures, and experimenting with light and shadow.

His drawings often possess a remarkable freedom and spontaneity, capturing the energy and dynamism that characterize his finished paintings. They demonstrate his mastery of anatomy and his ability to convey movement and expression with a few deft strokes. These preparatory sketches were crucial for planning his large-scale canvases, allowing him to resolve compositional challenges and refine figural arrangements before committing them to paint. The existence of these drawings underscores the intellectual rigor that underpinned his seemingly effortless and fluid painterly style. They show an artist deeply engaged in the classical tradition of careful preparation, even as his painted surfaces exuded a Baroque vibrancy.

Teaching and Influence: Shaping the Next Generation

Antonio Molinari was not only a successful painter but also an influential teacher. He ran an active studio in Venice, attracting a number of talented pupils who would go on to make their own significant contributions to Venetian art. His teaching style, likely emphasizing a strong foundation in drawing combined with a more expressive and color-oriented approach to painting, had a lasting impact on his students.

Among his most notable pupils was Giambattista Piazzetta (1683-1754). Piazzetta became one of the leading Venetian painters of the early 18th century, known for his emotionally resonant religious and genre scenes, his rich, earthy palette, and his masterful use of chiaroscuro, which, while distinct, shows an evolution from the dramatic lighting he would have encountered in Molinari's studio. Molinari's influence on Piazzetta can be seen in the younger artist's robust figure types and his ability to convey deep emotion, though Piazzetta developed a more introspective and less overtly theatrical style.

Another important student was Federico Bencovich (c. 1677-1753), also known as Bencovich or Ferighetto dalla Dalmazia. Bencovich developed a highly individualistic style characterized by elongated figures, dramatic lighting, and intense emotional expression, pushing the dynamism learned from Molinari in a more eccentric and mannered direction. His work, often with a mystical quality, found appreciation in Central Europe as well as Italy.

Giovanni Battista Pinerio is also mentioned as a student, though he is a less prominent figure in art historical records compared to Piazzetta and Bencovich. The impact of Molinari's teaching extended beyond his direct pupils, contributing to the broader shift in Venetian painting towards the lighter, more decorative, and sensuous qualities that would define the Rococo era in Venice, famously exemplified by artists like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who, while not a direct student, emerged from this evolving artistic climate. Molinari's emphasis on rich color and elegant forms helped pave the way for this next generation.

Contemporaries and Artistic Dialogue

Antonio Molinari worked during a period of rich artistic exchange in Venice. He was a contemporary of several other important painters who contributed to the city's vibrant art scene. Gregorio Lazzarini (1655-1730), an exact contemporary by birth year and another influential teacher (most notably of Tiepolo), offered a more classical and academic alternative to Molinari's more robust Baroque style. Lazzarini's work was characterized by its polished finish, clear compositions, and idealized figures.

Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675-1741) were slightly younger contemporaries who played crucial roles in disseminating the Venetian style across Europe. Ricci, in particular, developed a light, airy, and brilliantly colored style that prefigured the Rococo. Pellegrini, whose works were sometimes confused with Molinari's due to a shared fluidity and painterly freedom, also contributed to this lighter, more decorative trend. The works of these artists, alongside Molinari's, illustrate the dynamic evolution of Venetian painting at the turn of the 18th century.

Molinari's relationship with his former master, Antonio Zanchi, also provides an interesting point of comparison. While Molinari clearly moved beyond Zanchi's darker style, the foundational training in dramatic composition and narrative force remained. He transformed Zanchi's intensity into something more elegant and sensuous, demonstrating an independent artistic vision. He also navigated the influence of figures like Carl Loth, whose powerful, often turbulent, scenes were a significant presence in Venice. Molinari's art can be seen as a sophisticated response to these various artistic currents, forging a path that was both individual and reflective of broader European trends.

Later Years and Untimely Death

Antonio Molinari's career was productive and successful, earning him numerous commissions and a respected position within the Venetian artistic community. He continued to paint actively throughout the 1690s and into the early 1700s, refining his style and producing works that were highly sought after. His ability to combine narrative clarity with visual appeal made him a favorite for both public and private patrons.

Tragically, Antonio Molinari's flourishing career was cut short. He died in Venice on February 3, 1704, at the relatively young age of 49. His premature death deprived the Venetian art world of one of its most talented and innovative figures just as he was at the height of his powers. Had he lived longer, he might have played an even more direct role in the development of 18th-century Venetian painting.

Despite his relatively brief lifespan, Molinari left behind a substantial body of work that attests to his skill, versatility, and artistic vision. His death marked the end of a significant chapter in Venetian Baroque painting, but his legacy continued through the work of his students and the influence his style exerted on subsequent generations.

Critical Reception and Enduring Legacy

In his own time, Antonio Molinari was a highly regarded artist. The numerous commissions he received from churches and prominent Venetian families attest to his contemporary success. His ability to create large-scale, visually engaging narrative paintings was particularly valued. Early art historians and chroniclers of Venetian art, such as Antonio Maria Zanetti, acknowledged his talent, particularly praising his handling of color and his inventive compositions.

In subsequent centuries, as artistic tastes shifted, Molinari's reputation, like that of many Baroque artists, experienced periods of relative neglect. However, modern art historical scholarship has reassessed his contribution, recognizing him as a key transitional figure in Venetian painting. He is now seen as an important link between the more somber tenebrism of the mid-17th century and the luminous, decorative style of the 18th-century Venetian Rococo.

His influence on Giambattista Piazzetta is considered particularly significant. Piazzetta, while developing his own unique and powerful style, built upon the foundations laid by Molinari, particularly in terms of robust figural representation and expressive content. Molinari's emphasis on rich, harmonious color and elegant, sensuous forms also anticipated the aesthetic concerns that would dominate Venetian painting in the age of Tiepolo, Canaletto, and Guardi. His works are studied for their technical skill, their narrative power, and their embodiment of the late Baroque sensibility in one of Europe's most vibrant artistic centers.

Conclusion: Molinari's Place in Venetian Art History

Antonio Molinari was a painter of considerable talent and importance, whose career bridged the 17th and 18th centuries in Venice. Emerging from the dramatic tradition of tenebrism under Antonio Zanchi, he evolved a distinctive style characterized by rich coloration, dynamic compositions, and an elegant, often sensuous, treatment of the human form. His religious, historical, and mythological paintings adorned churches and palaces, captivating viewers with their narrative power and visual splendor.

As a respected teacher, he played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of Venetian artists, most notably Giambattista Piazzetta. Though his life was cut short, Molinari's artistic achievements and his influence on his successors ensure his lasting significance. He remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of Venetian painting, representing a vital moment of transition and innovation that paved the way for the final glorious chapter of the Venetian school in the 18th century. His works continue to be admired for their beauty, their drama, and their quintessential Venetian spirit.