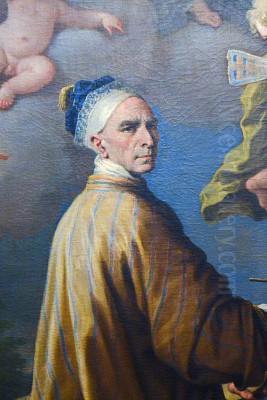

Paolo de Matteis stands as a significant figure in the vibrant artistic landscape of late 17th and early 18th-century Italy. Born on February 9, 1662, in Piano Vetrale, a small town in the Cilento region then part of the Kingdom of Naples (now in the province of Salerno), he rose to become one of Naples' most sought-after painters. His long and prolific career, ending with his death in Naples on January 26, 1728, witnessed a crucial transition in artistic taste, moving from the dramatic intensity of the High Baroque towards the lighter, more graceful elegance of the Rococo. De Matteis was not merely a follower of trends but an active participant in this stylistic evolution, forging a distinctive manner that blended influences while establishing his own artistic identity. His activity centered primarily in Naples, the bustling cultural capital of Southern Italy, but his reputation also led him to undertake significant commissions in Rome, Paris, and Genoa, spreading his influence across Europe.

Early Life and Formative Training under Giordano

De Matteis's artistic journey began when he moved to Naples, the dominant artistic center of the region. His exceptional talent likely became apparent early on, leading him to the prestigious workshop of Luca Giordano (1634-1705). Giordano, nicknamed "Luca fa presto" (Luke paints quickly) for his astonishing speed and prolific output, was the undisputed giant of Neapolitan Baroque painting. Training under such a master was formative for the young De Matteis. He absorbed Giordano's dynamic compositional structures, his vibrant and often warm palette, and his ability to handle large-scale fresco decorations with remarkable facility and energy.

The influence of Giordano remained a constant, albeit evolving, thread throughout De Matteis's career. In his early works, the connection is often quite direct, showing a clear emulation of his master's style. De Matteis learned how to orchestrate complex multi-figure scenes, infuse religious and mythological narratives with dramatic flair, and utilize color and light to create powerful effects. This grounding in the Neapolitan High Baroque tradition provided a robust foundation upon which he would later build his more personal style. The speed and efficiency he likely learned from Giordano would also serve him well, enabling him to complete large commissions, such as the Gesù Nuovo frescoes, with remarkable swiftness later in his career.

Roman Sojourn and Exposure to Classicism

Around 1682-1683, De Matteis traveled to Rome, a crucial step for any ambitious Italian artist of the period. Rome offered exposure to the masterpieces of antiquity, the High Renaissance, and the leading contemporary artists working in the papal city. This period was pivotal for broadening his artistic horizons beyond the Neapolitan milieu. While in Rome, he came into contact with the circle of Carlo Maratta (1625-1713), the preeminent painter in Rome at the time and the leading proponent of a more classical, restrained version of the Baroque.

Maratta's style, characterized by its compositional clarity, idealized figures, graceful poses, and somewhat cooler palette compared to the Neapolitan exuberance, offered a counterpoint to Giordano's dynamism. De Matteis absorbed elements of this Roman classicism, which tempered the purely painterly energy inherited from Giordano. This influence can be seen in a greater refinement in his drawing, a more controlled sense of order in his compositions, and an increased elegance in the depiction of figures. He did not abandon his Neapolitan roots, but the Roman experience added a layer of sophistication and classical poise to his developing style. Exposure to other Roman artists like Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccia), known for his illusionistic ceiling frescoes, may also have provided further inspiration.

Return to Naples: Rise to Prominence and Rivalry

Upon returning to Naples, De Matteis established himself as an independent master. The Neapolitan art scene was highly competitive, especially after Giordano spent significant time in Spain and eventually passed away in 1705. De Matteis quickly became one of the city's leading painters, securing numerous commissions for altarpieces, private devotional paintings, mythological scenes for palaces, and large-scale fresco decorations in churches. His ability to work efficiently and adapt his style to suit various patrons contributed to his success.

His primary rival in Naples during the early 18th century was Francesco Solimena (1657-1747). Solimena, also deeply influenced by Giordano but developing a powerful style characterized by dramatic chiaroscuro and robust figures, competed directly with De Matteis for major commissions. Their rivalry spurred both artists on, representing two dominant, though distinct, paths evolving from the legacy of Giordano. While Solimena often leaned towards more forceful drama and shadow, De Matteis increasingly cultivated an elegance and chromatic sweetness that anticipated the Rococo. This period saw De Matteis solidify his reputation, receiving patronage from the aristocracy, religious orders, and even international clients.

The De Matteis Style: A Synthesis of Eras

Paolo de Matteis's mature style is best understood as a sophisticated synthesis. It retained the compositional energy, narrative drive, and rich colorism of the Neapolitan Baroque, learned primarily from Luca Giordano. However, this foundation was refined by the classical sense of order and idealized grace absorbed from Carlo Maratta and the Roman school. Crucially, De Matteis infused this blend with a growing sensitivity towards the emerging Rococo aesthetic.

This Rococo sensibility manifested in several ways: a preference for lighter, more luminous color palettes, often featuring pastel blues, pinks, and yellows; elegant, elongated figures posed with graceful S-curves; a focus on tender emotions and charming details rather than overwhelming drama; and an overall decorative quality that suited the interiors of churches and palaces transitioning towards a lighter taste. He masterfully balanced narrative clarity with visual appeal, creating works that were both intellectually engaging and aesthetically pleasing. His technical skill was evident in both large-scale frescoes, where he demonstrated fluency and speed, and in easel paintings, characterized by a refined finish and delicate brushwork.

Masterworks: Religious Narratives and Devotion

Religious subjects formed the core of De Matteis's output, reflecting the demands of his primary patrons – the Church and devout nobility. His interpretations ranged from grand altarpieces to more intimate devotional works. Christ Delivering The Keys To St Peter, likely from the later 17th century, already shows his ability to handle a traditional theme with warmth and a softening of Baroque intensity, hinting at the elegance to come.

The Annunciation is another key example, often praised for its delicate portrayal of the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel, bathed in a soft, divine light. Works like The Worship of the Trinity demonstrate his capacity for complex theological subjects, sometimes directly referencing compositions by Giordano, yet executed with his own evolving stylistic signature. The Triumph of the Immaculate, dating around 1710-1714, showcases his ability to handle large, dynamic compositions filled with celestial figures, retaining Baroque energy while moving towards Rococo lightness.

Perhaps one of his most celebrated religious works is The Death of Saint Joseph. This painting is often cited as a prime example of the transition from Baroque to Rococo in Naples. The emotional tenderness of the scene, the gentle interplay of light and shadow, and the graceful arrangement of the figures (Christ, Mary, and the dying Joseph) exemplify De Matteis's mature style, balancing pathos with elegance. His ability to convey deep religious sentiment without resorting to excessive melodrama became a hallmark of his approach.

The Gesù Nuovo Commission: Speed and Scale

A testament to De Matteis's skill and reputation was the major commission to decorate parts of the important Jesuit church of Gesù Nuovo in Naples. In 1713, he undertook the demanding task of painting frescoes for the cupola pendentives and parts of the vaulting. Remarkably, according to contemporary sources, he completed this extensive work in just 66 days. This feat highlights not only his technical proficiency in the challenging medium of fresco but also the efficiency likely instilled during his training with Giordano.

The project undoubtedly presented significant challenges. Working at height on complex curved surfaces required careful planning and execution. Integrating the painted scenes with the existing architecture and sculptural decoration demanded a keen sense of design. Furthermore, the tight timeframe must have placed immense pressure on the artist and his workshop. The successful completion of the Gesù Nuovo frescoes solidified De Matteis's position as one of Naples' foremost monumental decorators, capable of handling large-scale projects with speed and artistic flair.

Masterworks: Mythology, Allegory, and History

Beyond religious themes, De Matteis also excelled in mythological and allegorical subjects, often commissioned for private palaces. These works allowed for a different kind of expression, often celebrating classical learning, aristocratic virtues, or contemporary events through symbolic language. His mythological paintings frequently depict scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses or tales of gods and heroes, such as Hercules at the Crossroads, treated with his characteristic elegance and refined sensuality.

He also tackled complex allegories, such as the Allegory of the War of the Spanish Succession, translating contemporary political struggles into the symbolic language of classical figures. These works demonstrate his intellectual engagement with the themes and his ability to create visually compelling narratives that flattered and instructed his patrons. The lighter, more decorative aspects of his style were particularly well-suited to these subjects, aligning with the tastes of the aristocracy in the early 18th century.

Controversy and Contemporary Reception

While generally successful and highly regarded, De Matteis was not immune to criticism or controversy. One notable example is his painting Religion Overcoming Heresy. This work depicts triumphant Catholic figures, including St. Ignatius of Loyola and St. Francis Xavier, along with Japanese martyrs, standing over defeated figures representing heresy, specifically including a depiction of the Prophet Muhammad and the Quran. In an era of religious conflict and sensitivity, such a direct and confrontational depiction was potentially provocative. Islamic tradition generally prohibits the depiction of prophets, making the image inherently controversial from a Muslim perspective, regardless of the artistic intent.

This work, while perhaps reflecting prevalent Catholic attitudes of the time, highlights the complex intersection of art, religion, and politics. Interestingly, despite or perhaps because of its charged subject matter, the composition later caught the attention of artists like William Blake and Salvador Dalí, who created works inspired by it, demonstrating its enduring, if controversial, impact. Contemporary reception wasn't always purely positive either; the Roman caricaturist Pier Leone Ghezzi sketched De Matteis, possibly hinting at a perception among some Roman rivals that the Neapolitan painter was overly ambitious or perhaps lacked the ultimate Roman gravitas.

A Prolific Teacher and His Enduring Influence

Paolo de Matteis was not only a productive painter but also ran a successful workshop, training numerous pupils and influencing a generation of Neapolitan artists. While specific names of all his direct pupils are not always clearly documented, his stylistic impact is undeniable. His blend of Giordano's energy, Maratta's grace, and nascent Rococo elegance provided a compelling model for younger painters.

Artists like Francesco De Mura (1696-1782) and Fedele Fischetti (1732-1792), who became leading figures of the Neapolitan Rococo and early Neoclassicism, clearly show the influence of De Matteis's refined style, particularly his lighter palette and graceful figure types. Other painters associated with his circle or influenced by him include Giuseppe Mastroleo and potentially members of the Sarnelli family of painters. Even Sebastiano Conca (1680-1764), though primarily active in Rome, shared a similar stylistic trajectory towards Rococo elegance and likely knew De Matteis's work well. De Matteis's role as a teacher and stylistic model was crucial in shaping the direction of Neapolitan painting in the first half of the 18th century.

International Reach and Later Years

De Matteis's fame extended beyond Naples and Rome. He spent time in Paris between 1702 and 1705, working for French patrons, including undertaking commissions for Louis XIV, although details of these specific works are sometimes debated. This period exposed him directly to French artistic trends, which may have further encouraged the development of the lighter, more elegant aspects of his style, aligning with the emerging French Rococo. He also worked in Genoa and received commissions from patrons across Europe, reflecting his international standing.

He remained active and highly sought after throughout his later years, continuing to produce a significant body of work until his death in Naples in 1728. His long career allowed him to witness and contribute to significant shifts in artistic style, maintaining a high level of quality and adaptability throughout. His works continued to be appreciated and collected long after his death, cementing his place in the history of Italian art.

Legacy: The Bridge Between Ages

Paolo de Matteis occupies a crucial position in the history of Neapolitan and Italian art. He was more than just a follower of Luca Giordano or a competitor to Francesco Solimena. He skillfully navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, forging a unique style that successfully bridged the gap between the dynamism of the late Baroque and the refined elegance of the Rococo. His ability to synthesize the painterly energy of Naples with the classical grace of Rome, all while infusing his work with a distinctive lightness and charm, set him apart.

His legacy lies in his extensive body of work, found in churches and museums across Italy and beyond, which exemplifies this important stylistic transition. It also lies in his significant influence on the subsequent generation of Neapolitan painters, particularly Francesco De Mura, who further developed the Rococo style in the city. De Matteis demonstrated that elegance and grace could coexist with narrative power and emotional depth. He remains a testament to the richness and complexity of the Neapolitan school and a key figure for understanding the evolution of European painting in the early 18th century. His art continues to be studied and admired for its technical brilliance, harmonious compositions, and captivating blend of artistic traditions.