Anthonis van den Wyngaerde, a name that resonates with the meticulous depiction of sixteenth-century urban landscapes, stands as a pivotal figure in the confluence of art, cartography, and royal patronage. Active during a transformative period in European history, his work offers an invaluable window into the appearance and structure of cities that have since been profoundly altered. As a Flemish artist in the service of one of the most powerful monarchs of the era, Philip II of Spain, Wyngaerde's legacy is etched in the detailed panoramas that captured the essence of burgeoning metropolises and strategic strongholds across Europe. His contributions extend beyond mere artistic representation, providing rich topographical data that continues to inform historians, urban planners, and art scholars alike.

Origins and Early Artistic Development in Flanders

Born likely around 1525, though some earlier accounts and guild records present ambiguities, Anthonis van den Wyngaerde is generally believed to have originated from Antwerp or its environs. The city of Antwerp, a bustling commercial and artistic hub in the Southern Netherlands, would have provided a fertile ground for a budding artist with an eye for detail. Records indicate that an "Anthonis van den Wyngaerde" was enrolled in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke, the city's venerable institution for painters and craftsmen, in 1510. If this refers to our artist, it would place his birth significantly earlier, perhaps closer to the late 15th century, making him an established master by the time he entered Philip II's service. However, the 1525 birth year is more commonly accepted by scholars, suggesting the 1510 entry might pertain to a relative, possibly his father, or is simply a point of ongoing scholarly discussion.

Regardless of the precise timeline of his early years, Wyngaerde's artistic training would have been steeped in the rich traditions of Flemish painting. The region was renowned for its mastery of oil painting, meticulous realism, and burgeoning interest in landscape, pioneered by artists like Joachim Patinir, who is often credited as one of the first true landscape specialists. While Patinir focused on expansive, often imaginary, world landscapes with religious or mythological scenes, the underlying attention to detail and panoramic scope would have been part of the artistic milieu. Wyngaerde's specialization in city views, or "vedute," can be seen as an evolution of this landscape tradition, focusing it onto the man-made environment with an almost scientific precision. His early works, such as views of Flemish towns like Dordrecht, demonstrate an emerging command of perspective and an ability to synthesize vast amounts of visual information into a coherent whole.

The Antwerp School, of which the Guild of Saint Luke was the epicenter, fostered an environment where artistic skill was highly valued and often involved collaborative efforts. Artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder, a contemporary of Wyngaerde, also based in Antwerp for a significant part of his career, showcased a similar interest in panoramic perspectives and detailed depictions of human activity within broader landscapes, though his focus was often more allegorical or genre-based. Wyngaerde’s approach, however, was more overtly topographical, aiming for a faithful, if artistically arranged, representation of the urban fabric.

The Italian Sojourn: Honing a Panoramic Vision

Before his extensive work in Spain, Wyngaerde is known to have traveled and worked in Italy during the 1550s. This period was crucial for many Northern European artists, offering exposure to classical antiquity and the monumental achievements of the Italian Renaissance. For a topographical artist like Wyngaerde, Italy presented a wealth of iconic urban subjects. His detailed panoramic drawing, Rome from the Gianicolo Hill (circa 1552-53), is a testament to his skill. This ambitious work captures the sprawling ancient city, meticulously rendering its famous monuments, churches, and the Tiber River.

During his time in Italy, he also depicted other significant cities, including Naples, Genoa, and Ancona. These Italian views demonstrate his evolving technique: often working from multiple vantage points, he would create preliminary sketches on-site, later combining them in the studio to construct a comprehensive, often slightly idealized, panorama. This method allowed him to include more information and a wider field of vision than a single viewpoint would permit, while still maintaining a high degree of recognizable accuracy. The influence of Italian Renaissance artists, perhaps even indirect exposure to the cartographic and engineering drawings of figures like Leonardo da Vinci, who had worked extensively on mapping and urban projects, might have further refined Wyngaerde's approach to representing space and form. The Italian tradition of detailed architectural representation, seen in the works of artists like Donato Bramante or Baldassare Peruzzi in their architectural drawings, could also have been an influence.

In Royal Service: Chronicling the Spanish Realm for Philip II

The most significant phase of Anthonis van den Wyngaerde's career began around 1557 when he entered the service of Philip II of Spain. Philip, a meticulous administrator and a significant patron of the arts, was keenly interested in having detailed visual records of his vast domains. Wyngaerde was tasked with creating a series of large-scale views of the principal cities and towns of Spain. This ambitious project was not merely for aesthetic pleasure; these images served strategic, administrative, and propagandistic purposes, showcasing the extent and grandeur of the Spanish crown's possessions.

For over a decade, Wyngaerde traveled extensively throughout Spain, meticulously documenting its urban centers. His process involved detailed on-site sketching, often from elevated viewpoints to achieve the desired panoramic effect. These sketches would then be elaborated into large, finished drawings, typically in pen and ink with wash, sometimes on multiple joined sheets of paper to accommodate the expansive vistas. His Spanish cityscapes are characterized by their remarkable detail, capturing not only major architectural monuments but also the general layout of streets, defensive walls, surrounding landscapes, and even aspects of daily life.

Among his most celebrated Spanish works are the panoramic views of Toledo Looking South (1563), a city that was then still a major political and religious center. His depiction of Toledo, perched dramatically on its gorge above the Tagus River, is a masterpiece of topographical art. Other notable Spanish views include those of Madrid (before it became the sprawling capital it is today), Seville (a vital port for trade with the Americas), Cordoba (with its great Mosque-Cathedral), Salamanca (renowned for its university), Málaga (1564), Segovia, Valladolid, and Granada. Each view is a testament to Wyngaerde's keen observational skills and his ability to translate complex three-dimensional urban forms onto a two-dimensional surface.

The precision of these works made them invaluable. They provided Philip II and his administrators with a visual understanding of the kingdom's key locations, potentially aiding in urban planning, military defense, and the overall governance of the realm. In this capacity, Wyngaerde’s work aligns with a broader Renaissance interest in cartography and accurate geographical representation, as seen in the contemporaneous efforts of mapmakers like Gerardus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius, whose Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (published in 1570) became the first true modern atlas. While Mercator and Ortelius focused on maps, Wyngaerde provided the "on-the-ground" visual reality of the cities themselves.

Wyngaerde's Artistic Method and Style

Anthonis van den Wyngaerde’s artistic style is defined by its commitment to detailed realism, combined with a sophisticated understanding of perspective and composition necessary for panoramic views. He typically employed a bird's-eye perspective, or an elevated oblique view, which allowed for both a sense of depth and the inclusion of a vast amount of information about the city's layout and its individual buildings.

His working method generally involved several stages. He would begin with on-site reconnaissance, identifying the best vantage points – often hills or towers surrounding the city. From these points, he would create numerous preliminary sketches, capturing specific buildings, sections of the city, and landscape features. These sketches, often annotated, served as his primary source material. Back in his studio, he would synthesize these individual observations into a single, coherent, large-scale composition. This often involved a degree of artistic license, subtly adjusting perspectives or the placement of certain features to achieve a more comprehensive or aesthetically pleasing result, without sacrificing the overall recognizability and topographical accuracy of the city.

The use of pen and ink, often with brown or grey washes to indicate shading and volume, was his preferred medium for these finished views. The lines are typically precise and controlled, allowing for the depiction of minute architectural details. Figures of people and animals are often included, adding a sense of scale and liveliness to the urban scenes, a characteristic also found in the works of his Flemish contemporaries like Pieter Bruegel the Elder or Lucas van Valckenborch, who also depicted cityscapes and landscapes populated with figures. Wyngaerde's technique sometimes involved a chalk transfer method to move elements from preparatory drawings to the final support, a common practice in Renaissance workshops.

His dedication to capturing the "portrait" of a city, rather than an idealized or generic urban form, sets him apart. While earlier artists had depicted cities, often they were symbolic or highly stylized. Wyngaerde, along with a few contemporaries like Joris Hoefnagel (who contributed many views to Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum), pushed towards a more empirical and visually accurate representation of specific urban environments.

Beyond Spain: Other Notable Commissions and Works

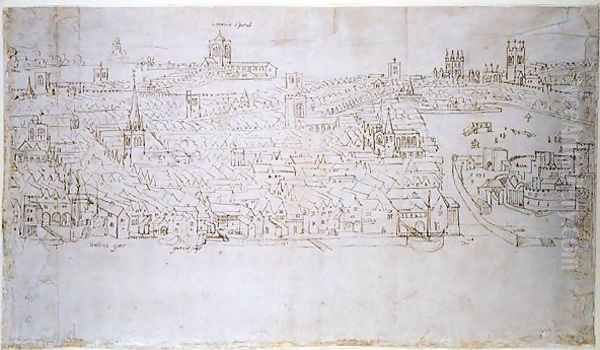

While his Spanish cityscapes form the core of his surviving oeuvre, Wyngaerde also undertook commissions and created views of cities outside of Iberia and Italy. His Panorama of London, created around 1543-1544, is one of the earliest and most comprehensive surviving depictions of the English capital before the Great Fire of 1666. Though parts of the original were damaged or lost (notably, a section depicting Billingsgate was reportedly damaged by fire much later, in the 18th century, not a fire during Wyngaerde's time related to the work's creation), the surviving sections, primarily housed in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and the Sutherland Collection, provide an unparalleled glimpse into Tudor London, detailing landmarks such as Old St Paul's Cathedral, the Tower of London, and London Bridge.

He also depicted cities in his native Low Countries, such as Brussels and Dordrecht, and was involved in recording military events. His detailed drawing of the Siege of Saint-Quentin (1557) showcases his ability to apply his topographical skills to the dynamic context of a military campaign, capturing the disposition of troops, fortifications, and the surrounding terrain. This type of work was also valued by rulers, providing visual records of important victories and strategic situations. The tradition of depicting battles and sieges was well-established, with artists like Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen having accompanied Emperor Charles V on military campaigns to record events.

A work titled The Coast of Africa (1564) is also attributed to him, suggesting his topographical interests extended beyond purely urban environments to coastal profiles, which were of immense importance in an age of maritime exploration and naval power. The Walcheren Panorama is another significant work from the Low Countries, showcasing his ability to capture extensive coastal and inland areas.

Contemporaneous Artistic Interactions and Influences

Anthonis van den Wyngaerde operated within a vibrant and interconnected European artistic network. While direct records of his personal interactions with many other famous artists are scarce, his work clearly reflects and contributes to broader artistic trends. His connection to the Antwerp School is fundamental. The city was a major center for printmaking, with publishers like Hieronymus Cock disseminating images, including landscapes and architectural views, across Europe. This culture of visual reproduction and exchange would have exposed Wyngaerde to a wide range of artistic styles and subjects.

His service to Philip II placed him in an environment where he might have encountered other court artists. Philip II's court attracted talent from across Europe. While Wyngaerde's specialization was distinct, he was part of a broader artistic program that included portraitists like Alonso Sánchez Coello and, for a time, the renowned Italian female painter Sofonisba Anguissola. The great Venetian master Titian was also a favored painter of Philip II (and his father Charles V), and though their artistic domains were very different, the king's appreciation for high-quality, detailed representation in portraiture might have extended to his expectations for topographical accuracy from Wyngaerde.

The most direct parallels to Wyngaerde's work can be found in the aforementioned Civitates Orbis Terrarum (published from 1572 onwards) by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg. This monumental atlas of city views, though appearing slightly later than much of Wyngaerde's primary output, shared a similar aim of systematically documenting the world's cities. Some of Wyngaerde's views, or copies thereof, may have even served as source material for later cartographers and publishers. His meticulous approach set a high standard for topographical art.

Unresolved Questions and Scholarly Debates

Despite the significance of his work, aspects of Wyngaerde's life and career remain subjects of scholarly discussion and some mystery. The precise dates of his birth and death (he is thought to have died in Madrid in 1571) are not definitively established, leading to the aforementioned confusion regarding his entry into the Antwerp Guild.

The question of his identity has also been debated. Some scholars have explored a possible connection or confusion with an artist named "Antonio de las Viñas" (which translates to "Anthony of the Vineyards," a name phonetically similar to Wyngaerde, meaning "vineyard" in Dutch/Flemish). While this identification is not universally accepted, it highlights the challenges in piecing together biographical details for artists of this period from fragmented records.

The exact purpose and intended use of all his drawings also invite speculation. While many were clearly official commissions for Philip II, the extent to which they were used for practical administrative or military planning versus serving as symbols of royal power and knowledge, or even as decorative pieces for royal palaces like the Escorial, is a nuanced question. Some scholars have suggested that the artistic embellishments and slight deviations from strict perspective in some views point towards a greater emphasis on aesthetic appeal than purely utilitarian function.

Furthermore, many of his works were dispersed after his death, and their full importance was not recognized until the 19th and 20th centuries when scholars began to systematically study and catalogue them. The loss of some works, like portions of the London panorama or drawings potentially destroyed in palace fires (such as the 1734 fire at the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, where many royal collections were housed), means our understanding of his total output is incomplete.

Legacy and Enduring Importance

Anthonis van den Wyngaerde's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he was a master of the panoramic city view, demonstrating exceptional skill in observation, draftsmanship, and composition. His works are not merely picturesque scenes but are imbued with a sense of order and clarity, reflecting the Renaissance desire to understand and represent the world with increasing accuracy.

For historians, his drawings are invaluable primary sources. They provide detailed visual evidence of the appearance of 16th-century cities, many of which have undergone radical transformations due to war, natural disasters, urban development, or decay. His views of London, Rome, and numerous Spanish cities allow us to reconstruct past urban environments, study architectural history, and understand the spatial organization of early modern urban life. They are crucial documents for urban historians and historical geographers.

In the context of cartography, while not a mapmaker in the traditional sense of creating planimetric maps, Wyngaerde's topographical views contributed to the broader project of visually documenting the known world. His work can be seen as a bridge between artistic landscape painting and more scientific forms of geographical representation. The precision and informational density of his city "portraits" were unparalleled for their time in terms of individual, large-scale depictions.

His service to Philip II also highlights the important role of royal patronage in fostering artistic and scientific endeavors during the Renaissance. The king's desire to possess a comprehensive visual inventory of his realm provided Wyngaerde with the opportunity to create his extensive body of work.

Conclusion: A Cartographer of Urban Souls

Anthonis van den Wyngaerde died in Madrid around 1571, leaving behind a remarkable corpus of work that continues to fascinate and inform. His meticulous panoramas are more than just pictures of cities; they are historical documents, artistic achievements, and windows into the ambitions and worldview of the 16th century. He captured not just the stones and streets, but something of the character and presence of these urban centers at a specific moment in their history. In an era of burgeoning empires and expanding global consciousness, Wyngaerde provided a visual language to comprehend and appreciate the complex, evolving organisms that were Europe's cities. His eye for detail, his sweeping perspectives, and his dedication to his craft ensure his place as one of the foremost topographical artists of the Renaissance, a true cartographer of urban souls whose work remains a vivid testament to a world both lost and preserved through his art.