Anton Romako stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 19th-century Austrian art. An artist whose work navigated the currents between Biedermeier realism, the grandeur of historicism, and the burgeoning psychological intensity that would herald Expressionism, Romako's life and art were marked by both significant achievement and profound personal struggle. Often misunderstood or overlooked during his lifetime, his unique vision and innovative techniques earned him posthumous recognition as a crucial precursor to Viennese Modernism. His journey through the artistic centers of Europe and his eventual, difficult return to Vienna paint a portrait of an artist grappling with tradition, innovation, and the complexities of his era.

Early Life and Formative Years

Anton Romako was born on October 20, 1832, in Atzgersdorf, then a suburb of Vienna, now part of the Liesing district. His origins were modest; he was the illegitimate son of Josef Lepper, a factory owner, and Elisabeth Maria Anna Romako, who worked as a housemaid. This circumstance perhaps foreshadowed a life lived somewhat outside the conventional structures of society. His artistic inclinations led him to the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where he studied from 1847 to 1849.

His time at the Vienna Academy was not auspicious. His tutor, the prominent Biedermeier painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, famously assessed Romako as lacking talent, a judgment that might have deterred a less determined individual. Undeterred, Romako left Vienna and sought further training in Munich in 1849. While some accounts mention study under Wilhelm von Kaulbach, a key influence during this period and into the early 1850s back in Vienna was Carl Rahl. Romako took private lessons from Rahl, a master known for his monumental historical paintings and a significant teacher whose pupils also included the later Viennese star, Hans Makart. Rahl's influence likely imparted a sense of historical scale and technical facility, though Romako would ultimately diverge significantly from his teacher's style.

Following his studies in Munich and Vienna, Romako embarked on extensive travels, a common practice for aspiring artists of the time seeking broader exposure and inspiration. He journeyed through Italy, spending time in Venice and Rome, and also visited Spain and London between 1854 and 1857. These travels exposed him to a rich tapestry of artistic traditions, from the Venetian masters' use of color and light to the dramatic intensity of Spanish Baroque and the classical heritage of Rome, all of which would subtly filter into his developing artistic language.

The Roman Zenith

In 1857, Anton Romako chose Rome as his base, settling there for nearly two decades. This period marked a significant phase of professional success and personal development. Rome, a magnet for international artists and patrons, provided a fertile ground for Romako. He quickly established himself as a sought-after painter within the expatriate community, excelling in portraiture, genre scenes, and landscapes. His ability to capture not just a likeness but also a sense of the sitter's inner life distinguished his portraits.

During his Roman years, Romako's style began to fully crystallize. While grounded in realistic observation, his work increasingly showed a penchant for dramatic lighting, often employing deep shadows and contrasting highlights reminiscent of Baroque masters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. He shared certain affinities with other German-speaking artists working in Italy around that time, such as the portraitist Franz von Lenbach and the symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin, particularly in their exploration of darker palettes and psychological depth. However, Romako's brushwork often possessed a freedom and expressiveness that set him apart.

His personal life also saw significant developments during this time. In 1862, he married Sophie Köbel, the daughter of architect Karl Köbel. The couple had children, but the marriage would later face severe difficulties. Professionally, however, Rome was a period of relative stability and recognition, supported in part by patrons like Count Kuefstein. He produced numerous portraits, landscapes capturing the Italian countryside, and genre scenes reflecting local life, all imbued with his increasingly individualistic style.

Return to Vienna: Struggle and Tragedy

Romako returned to Vienna in 1876, perhaps hoping to capitalize on his reputation established abroad. However, the artistic climate in the imperial capital proved challenging. The Viennese art scene was largely dominated by the opulent, historically-themed decorative style championed by his former colleague Hans Makart. Romako's more intense, psychologically probing, and less conventional style struggled to find favor with the Viennese public and critics, who preferred Makart's sensual and theatrical canvases.

This period was also marked by profound personal tragedy. His marriage, already strained, effectively ended when Sophie left him around 1875. Sources indicate she later formed a relationship with, and eventually married, Hans Makart, adding a layer of personal and professional rivalry to Romako's difficulties. The emotional toll was immense, compounded by the tragic fate of his daughters, Mathilde and Mary. Accounts suggest they faced extreme hardship, with some sources citing poverty and others mentioning suicide, painting a grim picture of the family's decline.

Unable to secure consistent patronage or critical acclaim in Vienna, Romako faced increasing financial hardship. His later years were spent in relative poverty and obscurity, a stark contrast to his earlier success in Rome. He continued to paint, producing some of his most powerful and unconventional works during this difficult time, but recognition remained elusive. Anton Romako died in Vienna on March 8, 1889, at the age of 56. He was buried in the Vienna Central Cemetery (Zentralfriedhof).

Artistic Style: A Unique Vision

Anton Romako's artistic style is complex and resists easy categorization. He emerged from the Biedermeier tradition exemplified by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, with its emphasis on detailed realism and often sentimental subject matter. However, Romako transcended these origins, infusing his work with a dramatic intensity and psychological depth that looked forward to Expressionism. His training under Carl Rahl provided a foundation in historical painting and solid technique, but Romako's application of paint became increasingly free and unconventional.

A key characteristic of Romako's mature style is his dramatic use of chiaroscuro – the play of light and shadow. Influenced perhaps by his study of Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and possibly Spanish masters like Velázquez during his travels, he employed strong contrasts not merely for naturalistic effect but to heighten emotional impact and focus attention. His palettes often leaned towards darker tones, creating a sense of brooding intensity or melancholy, particularly in his portraits and later historical scenes.

His brushwork became notably free and expressive, especially in his later years. Rather than smooth, academic finishes, he often used visible, dynamic strokes that conveyed energy and emotion, sometimes at the expense of precise detail. This technique contributed to the psychological charge of his portraits, where he seemed less interested in flattering likenesses or social status than in capturing the sitter's inner state, anxieties, or eccentricities. This approach set him apart from the polished surfaces of academic painting and the decorative richness of Makart.

Even in landscapes and genre scenes, Romako's unique vision prevailed. His landscapes often possess a dramatic, almost unsettling quality, while his genre scenes could explore unusual or psychologically charged moments. His refusal to conform entirely to the prevailing tastes of the Ringstrasse era, dominated by historicism and Makart's decorative flair, contributed to his marginalization during his lifetime but cemented his importance for later generations seeking alternatives to academic convention.

Masterworks and Themes

Among Romako's most significant and discussed works is Admiral Tegetthoff in the Naval Battle of Lissa (painted around 1878-1880). This painting is a radical departure from traditional heroic battle scenes. Instead of a panoramic view or a clear narrative sequence, Romako compresses the action dramatically. Admiral Tegetthoff and his officers are depicted on the bridge of the flagship just moments after a collision, amidst the chaos and smoke of battle. The composition is tight, almost claustrophobic, the figures rendered with urgent, expressive brushstrokes. It captures the visceral intensity and confusion of naval warfare in a way that was startlingly modern, breaking conventions of historical painting established by artists like his former teacher Rahl. The work was controversial at the time but is now seen as a landmark of innovative historical representation.

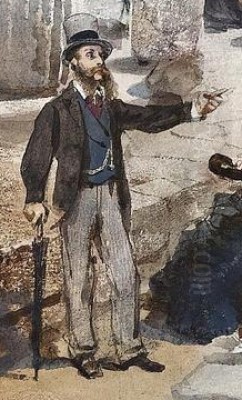

Another key area was portraiture. The Portrait of Babette Tapie (sometimes cited as Babette Pieter), painted in 1876, exemplifies his skill in capturing psychological nuance. The subject is presented with an unsettling directness, her expression ambiguous, rendered with the characteristic interplay of light and shadow and expressive brushwork that suggests a complex inner life. His numerous portraits of Roman and Viennese society figures, as well as more intimate portrayals like his Self-Portrait (c. 1860), consistently demonstrate this focus on individuality and psychological depth over mere representation.

Other notable works touch upon different aspects of his oeuvre. A Young Girl (Nude) became subject to provenance disputes related to Nazi-era confiscation, highlighting the complex histories some artworks carry. His watercolors, such as the pair titled Hunting Dogs, reveal his skill in a different medium, showcasing a similar energy in line and form. His genre scenes, often depicting Italian life, also carry his distinctive stylistic signature. Throughout his diverse output, a consistent thread is his unique blend of realism, dramatic intensity, and psychological exploration.

Network of Influences and Contemporaries

Romako's artistic journey was shaped by a diverse network of influences and interactions. His early teachers, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller and Carl Rahl, provided foundational training in realism and historical painting, respectively, even if Romako ultimately forged his own path, reacting against or transforming their lessons. His travels exposed him to the great European traditions, with the dramatic lighting of Caravaggio and Rembrandt, and potentially the psychological intensity of Spanish masters like Velázquez, leaving discernible marks on his style.

In Rome, he moved within an international circle, and his work shows parallels with contemporaries like Franz von Lenbach and Arnold Böcklin, who similarly explored realism tinged with psychological depth or symbolism. His relationship with Hans Makart was complex, evolving from fellow student under Rahl to a rival whose overwhelming success in Vienna overshadowed Romako's return, further complicated by Makart's relationship with Romako's estranged wife, Sophie.

While Romako worked largely outside the mainstream Viennese art establishment of his later years, his individualism and expressive style resonated with a later generation. Though he predated the Vienna Secession, artists like Gustav Klimt and especially the Expressionists Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka can be seen as heirs to the psychological intensity and formal experimentation that Romako pioneered in Austrian art. His work provided a crucial precedent for breaking away from academic constraints towards a more personal and emotionally charged form of expression. The collector and artist Carl Moll, a key figure in the Secession, also showed interest in Romako's work, as evidenced by the provenance of one of the Hunting Dogs watercolors.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Despite his success in Rome, Anton Romako remained largely underappreciated in Vienna during his later life and died in relative obscurity. The prevailing taste favored the decorative historicism of Makart and the Ringstrasse era, leaving little room for Romako's more challenging and introspective art. His unconventional techniques and psychological focus were often perceived as eccentric or even technically deficient by contemporary critics accustomed to academic polish.

However, the early 20th century brought a significant reappraisal of his work. As artistic tastes shifted towards Modernism and Expressionism, Romako's paintings were rediscovered and hailed for their innovation and emotional power. Pivotal exhibitions, particularly those held at the Galerie Miethke in Vienna in 1905 and 1913, played a crucial role in rehabilitating his reputation and establishing his importance. Critics and artists began to recognize him as a significant forerunner of Austrian Expressionism, an artist ahead of his time.

Today, Anton Romako is considered a major figure in 19th-century Austrian art. His works are held in prestigious collections, including the Belvedere Museum and the Leopold Museum in Vienna, and are studied for their unique blend of realism, psychological insight, and proto-Expressionist technique. He is acknowledged not just for individual masterpieces like the Tegetthoff painting, but for his overall contribution to diversifying the Austrian artistic landscape and anticipating key developments of modern art.

Anecdotes and Specific Histories

Several anecdotes and specific histories add color to Romako's biography and the afterlife of his works. One interesting episode involves his connection to Mozart. Romako created a painting intended for Mozart's birthplace in Salzburg and, in a letter from the winter of 1877 to a certain Carl Sterneck, expressed deep admiration for the composer, particularly the opera The Magic Flute. He hoped his painting would be worthy of the location and even suggested selling it to benefit the foundation managing the house, showcasing his reverence for the composer.

The provenance of some of his works reflects turbulent historical events. The painting A Young Girl (Nude) was once in the collection of Dr. Oskar Reichel, a Jewish collector in Vienna. Following the Anschluss in 1938, the painting was confiscated by the Nazi regime. It later entered the collection of Rudolf Leopold and was subsequently donated to the Leopold Museum Private Foundation. Its ownership history has been the subject of scrutiny and restitution claims by Reichel's heirs, highlighting the ongoing challenges of addressing Nazi-era art looting.

Another interesting discovery occurred in 2005 when two nearly identical watercolor versions of Hunting Dogs surfaced. One was linked to the collection of Armin Reichmann, while the other potentially came from the estate of Carl Moll, the Secessionist artist, further linking Romako to the generation that would later champion his work. Additionally, the Portrait of Babette Tapie (Pieter) found its way into the collection of the Belvedere via the city of Eppingen, Germany, after being acquired by Diana Kraus in 1979, demonstrating the continued appreciation and circulation of his art long after his death.

Conclusion

Anton Romako remains a compelling figure in art history, an artist whose career traversed geographical and stylistic boundaries. From his early academic training and rejection by Waldmüller to his success in Rome and subsequent struggles in Vienna, his life was one of contrasts. Artistically, he occupied a unique space between the detailed observation of Realism and the emotional intensity and formal freedom that anticipated Expressionism. His innovative approach to portraiture, focusing on psychological depth, and his radical reconception of history painting in works like the Tegetthoff battle scene, mark him as an important innovator.

Though largely unrecognized by the Viennese establishment during his lifetime, his posthumous rediscovery secured his place as a key precursor to Austrian Modernism. Artists like Schiele and Kokoschka are indebted to the path Romako helped forge towards a more subjective and expressive art. Today, Anton Romako is celebrated for his technical skill, his profound psychological insight, and his courageous, often eccentric, artistic vision that dared to challenge the conventions of his time. He stands as a testament to the individualistic spirit in art, a bridge between centuries and styles.