Introduction: A Talent from Cornwall

John Opie (1761-1807) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late 18th and early 19th-century British art. Emerging from a modest background in rural Cornwall, his raw, innate talent propelled him into the heart of the London art world, where he quickly gained fame as a portraitist and history painter. Known affectionately and sometimes dismissively as "The Cornish Wonder," Opie's career was marked by a distinctive, powerful style, a dedication to realism, and a complex relationship with the academic traditions of his time. His work, characterized by dramatic lighting and an unvarnished portrayal of his subjects, offers a compelling counterpoint to the more polished elegance of many of his contemporaries.

Early Life and the Discovery by Wolcot

Born in Harmony Cottage, Trevella, near St Agnes in Cornwall, John Opie was the son of Edward Opie, a master carpenter. From a very young age, he displayed remarkable intellectual and artistic precocity. Eschewing the expected path of following his father's trade, young Opie demonstrated a flair for mathematics and drawing. By the age of twelve, he had reportedly mastered Euclidean geometry and was sufficiently advanced to set up a small evening school, teaching reading, writing, and arithmetic to local children, showcasing an early independence and drive.

His artistic inclinations did not go unnoticed for long. Around 1775, his burgeoning talent caught the eye of Dr. John Wolcot, a local physician, satirist (writing under the pseudonym Peter Pindar), and amateur artist residing in Truro. Wolcot became Opie's first significant mentor and patron. Recognizing the boy's potential, Wolcot provided him with materials, rudimentary instruction in the techniques of drawing and painting, and access to his own collection of pictures for copying. He effectively took Opie under his wing, offering guidance and, crucially, encouragement to pursue art seriously.

Wolcot's support was instrumental. He not only nurtured Opie's skills but also began promoting him locally. Opie started painting portraits of local families, honing his craft and building a regional reputation. Wolcot saw the potential for greater things and understood that London was the necessary stage for Opie's talent to truly flourish. This relationship, though foundational, would later become more complex as Opie sought artistic independence.

The London Debut: "The Cornish Wonder"

In 1781, armed with ambition and facilitated by the entrepreneurial Dr. Wolcot, John Opie arrived in London. Wolcot acted as his promoter, strategically presenting him to the capital's fashionable society. Opie was marketed as an untutored genius, a natural talent sprung from the remote wilds of Cornwall – hence the nickname "The Cornish Wonder." This narrative captured the public imagination, fueled by the Romantic era's fascination with innate genius and the 'primitive'.

The impact was immediate and sensational. London society flocked to Opie's studio. His style, raw and forceful, stood in stark contrast to the refined elegance popularized by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Opie's portraits were noted for their strong chiaroscuro – dramatic contrasts between light and shadow reminiscent of Old Masters like Rembrandt and Caravaggio – and their unflinching realism. He did not flatter his sitters in the conventional manner; instead, he captured a sense of rugged character and psychological presence.

This initial blaze of fame brought commissions from the aristocracy and notable figures. King George III himself was intrigued by the phenomenon and sat for Opie, further cementing his fashionable status. However, the label of "wonder" was a double-edged sword. While it brought attention, it also carried connotations of novelty and perhaps a lack of sophisticated training, a perception that would follow Opie throughout his career. His direct, sometimes unrefined technique was both his strength and a point of criticism.

Artistic Style and Influences

John Opie's artistic style is defined by its vigour, directness, and dramatic use of light and shadow. Largely self-taught, though guided initially by Wolcot, he developed a technique rooted in observation rather than academic convention. His handling of paint could be bold, even coarse, emphasizing texture and form over smooth finish. This gave his work an immediacy and power that set it apart.

His primary influence appears to be the Baroque masters known for their dramatic realism and tenebrism. Echoes of Rembrandt van Rijn are evident in the psychological depth of his portraits and the manipulation of light to reveal character. The stark contrasts and earthy palettes found in the works of Caravaggio and Spanish masters like Jusepe de Ribera and Diego Velázquez also seem to inform Opie's approach. He absorbed these influences not through formal travel or study in his youth, but likely through prints and the collections he encountered via Wolcot and later in London.

Compared to his leading British contemporaries, Opie offered a different vision. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, advocated for the "Grand Manner," often idealizing sitters and referencing classical art. Thomas Gainsborough was celebrated for his fluid brushwork and elegant, often ethereal, portrayals. George Romney offered a fashionable, somewhat neoclassical grace. Opie's work, by contrast, felt more grounded, intense, and less concerned with fashionable elegance. His realism was less about minute detail and more about capturing the essential character and physical presence of the sitter, often with a certain rugged honesty.

While sometimes criticized for a lack of refinement or a tendency towards heavy, dark tones, Opie's style possessed undeniable strength. His commitment to portraying subjects without excessive flattery, combined with his mastery of dramatic lighting, resulted in portraits of compelling psychological intensity and history paintings with considerable narrative force.

Portraiture: Capturing Character

Portraiture remained the bedrock of John Opie's career, providing his primary source of income and public recognition. His approach was characterized by a direct, often unidealized realism. He sought to capture the character and substance of his sitters, rather than merely their superficial likeness or social standing. This often resulted in portraits that feel remarkably modern in their psychological penetration.

Among his most notable portraits is that of the writer and early feminist thinker, Mary Wollstonecraft (c. 1797, Tate Britain). The portrait is striking for its direct gaze and lack of adornment, conveying Wollstonecraft's intellectual intensity and strength of character. It avoids conventional tropes of female portraiture, presenting her as a serious and formidable individual.

His portrait of his second wife, Amelia Opie (née Alderson) (1798, National Portrait Gallery, London), is another key work. It shows Amelia, herself a successful novelist and poet, looking thoughtfully towards the viewer. Opie captures her intelligence and sensitivity, again using strong light and shadow to model her features and create a sense of presence. His self-portraits, too, are revealing, often depicting him with a serious, searching expression, reflecting his intense personality.

Opie painted many other prominent figures of his day, contributing significantly to the visual record of late Georgian Britain. While his initial burst of fame as the "Cornish Wonder" eventually subsided, he maintained a steady practice. His portraits were valued for their strength and honesty, even if they lacked the fashionable grace of artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, who rose to prominence slightly later. Opie's commitment to realism meant his work sometimes fell out of favour when smoother, more flattering styles were preferred, but it also ensures its enduring power and historical interest.

History Painting and Ambition

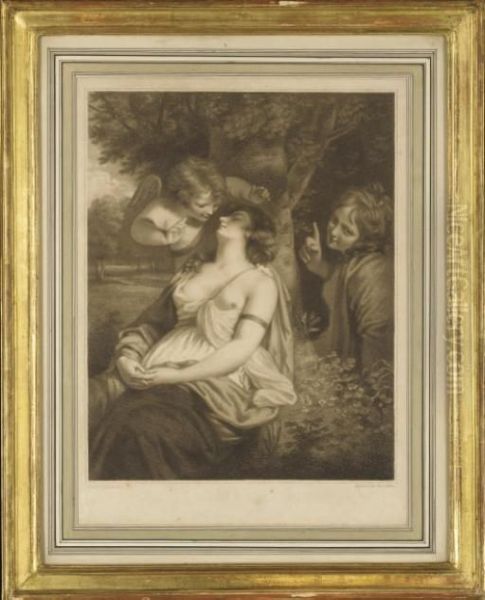

While portraiture provided his livelihood, John Opie, like many ambitious artists of his era, aspired to success in history painting. Considered the highest genre of art according to academic theory, history painting allowed artists to tackle grand themes from mythology, religion, literature, and history, demanding compositional skill, anatomical knowledge, and narrative power. Opie made significant contributions in this field, most notably for John Boydell's ambitious Shakespeare Gallery project.

Launched in 1786, Boydell's Gallery aimed to foster a British school of history painting by commissioning leading artists to create works based on Shakespeare's plays, which were then exhibited and disseminated through engravings. Opie was a major contributor, producing powerful and dramatic scenes such as The Murder of James I of Scotland, Arthur and Hubert, Juliet on her Bier, and The Death of Rizzio. These works showcased his talent for dramatic composition and intense emotion, often employing the strong chiaroscuro characteristic of his portraits.

Opie also contributed illustrations for other significant publishing ventures, including Thomas Macklin's Poets' Gallery and Robert Bowyer's Historic Gallery, which commissioned paintings illustrating British history. These projects provided crucial outlets for history painting at a time when private patronage for such large-scale works was limited.

Despite these successes, Opie, like his contemporary James Northcote (another painter who balanced portraiture with historical ambitions), likely felt the tension between the financial security of portrait painting and the artistic prestige associated with history painting. The market for history paintings was less reliable, and Opie's desire to dedicate more time to this genre may have been constrained by economic realities. His history paintings, while perhaps less numerous than his portraits, demonstrate his considerable skill in narrative and dramatic representation, solidifying his place among the key figures of British history painting in his generation.

The Royal Academy: Recognition and Teaching

John Opie's integration into the British art establishment was formalized through his involvement with the Royal Academy of Arts in London. His talent, despite his unconventional beginnings, was recognized by his peers. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1787 and achieved the status of full Royal Academician (RA) the following year, in 1788. This election placed him among the leading artists of the nation, including figures like Benjamin West, who succeeded Reynolds as President, and the visionary painter Henry Fuseli.

His standing within the Academy grew over the years. In 1805, Opie was appointed Professor of Painting, a prestigious position previously held by artists like James Barry and Fuseli. This role involved delivering a series of lectures to the Academy's students, offering theoretical and practical insights into the art of painting. Opie took this responsibility seriously, preparing lectures that reflected his own artistic principles.

His lectures emphasized the importance of originality, direct study from nature, and a powerful, expressive approach to art. He drew upon his knowledge of the Old Masters, particularly those of the Venetian and Flemish schools, but cautioned against slavish imitation. He admired painters like Titian for their colour and Rembrandt for his light and shadow, advocating for a style grounded in truth and emotional force rather than superficial mannerism. He was critical of what he saw as affectation or weakness in art, championing strength and sincerity.

Opie delivered his first course of lectures in 1806 but sadly died in April 1807 before he could complete a second series. His lectures were published posthumously in 1809, edited by his widow Amelia Opie, accompanied by a memoir. They provide valuable insight into his artistic philosophy and his views on his contemporaries and predecessors, confirming his status not just as a practitioner but also as a thoughtful commentator on art. His younger contemporary, J.M.W. Turner, was also lecturing at the RA during this period, highlighting a time of vibrant discussion about the direction of British art.

Personal Life, Connections, and Rivalries

John Opie's personal life was intertwined with his artistic career and the social circles of London. He married twice. His first marriage, in 1782, was to Mary Bunn. This union proved unhappy and was dissolved by Act of Parliament in 1796, a relatively uncommon occurrence at the time.

His second marriage, in 1798, was to Amelia Alderson, a well-regarded novelist, poet, and later, a prominent Quaker and abolitionist from Norwich. Amelia Opie was a significant figure in her own right, part of a lively intellectual and literary circle. Their marriage appears to have been a supportive partnership. Amelia admired John's talent and character, and after his death, she championed his legacy, most notably by editing and publishing his Royal Academy lectures with a memoir. Their home became a gathering place for artists and writers.

Opie's relationship with his initial mentor, Dr. John Wolcot, evolved over time. While indebted to Wolcot for his early support and promotion, Opie eventually sought to establish his own identity and distance himself from Wolcot's sometimes controversial persona and perhaps controlling influence. This separation was a necessary step for Opie's artistic independence but likely caused friction.

He maintained connections with key figures in the art world. His early introduction to Sir Joshua Reynolds was significant, although their styles differed considerably. He knew Benjamin West, Reynolds' successor as RA President, and encountered artists like Maria Cosway, an accomplished miniaturist and history painter, and perhaps Angelica Kauffman, another prominent female RA member, within the Academy circles. He also had professional relationships, sometimes tinged with rivalry, with contemporaries like James Northcote, who shared a similar background (provincial origins, initial support from Reynolds) and ambitions in history painting. Opie's direct and sometimes blunt manner might have complicated some relationships, but he was generally respected for his talent and integrity. His trip to Paris in 1802 during the Peace of Amiens allowed him to see masterpieces gathered by Napoleon, an experience shared with other British artists like West and Fuseli.

Later Career, Reputation, and Legacy

In the later years of his career, John Opie remained a respected figure, particularly within the Royal Academy, culminating in his professorship. However, the intense public fascination that marked his debut as "The Cornish Wonder" had inevitably cooled. Artistic tastes shifted, and the smoother, more flattering styles of portraiture, exemplified by the rising star Sir Thomas Lawrence, gained increasing popularity among fashionable patrons.

Opie's reputation during his lifetime and posthumously has fluctuated. His powerful, realistic style continued to be admired for its strength and honesty, but it was also criticized by some for its perceived lack of refinement, its occasionally somber palette, and its "coarse" brushwork – criticisms often linked to his lack of formal academic training. Yet, this very directness and lack of artifice is precisely what gives his work much of its enduring appeal. He captured a sense of rugged individuality, particularly in his male portraits, that feels authentic and compelling.

His contribution to history painting, especially through the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, was significant in promoting narrative art in Britain. While perhaps overshadowed in this genre by contemporaries like Benjamin West or Henry Fuseli in terms of imaginative scope, Opie brought a dramatic intensity and psychological realism to his historical subjects.

John Opie died relatively young, at the age of 45, on April 9, 1807, at his home in Berners Street, London. His death was reportedly hastened by overwork. In a mark of the high esteem in which he was held by the artistic establishment, he was granted the honour of burial in St Paul's Cathedral, in the area now known as Artists' Corner, near the tomb of Sir Joshua Reynolds. This placement symbolized his recognized status as a major figure in the British school of painting.

His legacy lies in his powerful and direct contribution to British portraiture and history painting. He stands as a bridge between the era of Reynolds and Gainsborough and the subsequent generation. His work influenced later artists who valued realism and strong characterization. Though perhaps not always enjoying the consistent high profile of some contemporaries, John Opie remains a vital and distinctive voice in British art history, admired for his raw talent, his psychological insight, and his unwavering commitment to a forceful, honest portrayal of the world around him. His journey from a carpenter's son in Cornwall to a Royal Academician buried in St Paul's is a testament to his extraordinary ability and determination.

Conclusion: An Enduring Force

John Opie's career exemplifies the potent combination of innate talent and determined ambition. Emerging from outside the established pathways of artistic training, he forged a unique style characterized by dramatic intensity, psychological depth, and a commitment to realism that often eschewed conventional flattery. As "The Cornish Wonder," he captivated London, and though fashions changed, he remained a significant force in British art through his powerful portraits and compelling history paintings. His work for Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and his role as Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy underscore his importance. Remembered for his strong chiaroscuro, vigorous brushwork, and insightful character studies, Opie carved a distinct niche, offering a robust counterpoint to the elegance of Reynolds or Gainsborough and the burgeoning Romanticism of Fuseli or Blake. His legacy endures in works that convey a powerful sense of presence and an honest, often rugged, portrayal of humanity, securing his place as a key figure in the rich tapestry of British art.