Doménikos Theotokópoulos, universally known by his nickname El Greco ("The Greek"), stands as one of the most distinctive and influential figures in the history of Western art. Born in 1541 on the island of Crete, then a possession of the Republic of Venice known as the Kingdom of Candia, his life and art represent a fascinating synthesis of diverse cultural and artistic traditions. Trained initially as an icon painter in the post-Byzantine style, his journey took him through the vibrant artistic centers of Venice and Rome before he ultimately settled in Toledo, Spain, where he produced the works that would secure his unique and enduring legacy. El Greco was not only a painter but also a sculptor and architect, a true Renaissance man whose vision, however, transcended the aesthetic norms of his time, foreshadowing artistic developments centuries later.

Early Life and Artistic Formation: From Crete to Italy

El Greco's artistic journey began in Candia (modern Heraklion), a thriving cultural crossroads where Eastern and Western traditions met. Here, he mastered the techniques of post-Byzantine icon painting, characterized by its stylized figures, flattened perspective, and spiritual intensity. This early training instilled in him a focus on the spiritual and symbolic potential of art, a foundation that would remain crucial throughout his career, even as his style evolved dramatically. Evidence suggests he was already a recognized master painter in Crete before venturing westward around the age of 26.

Seeking broader artistic horizons, El Greco traveled to Venice, the dominant power in the Mediterranean and a leading center of the Italian Renaissance. Immersing himself in the Venetian school, he absorbed the lessons of its greatest masters. The rich, vibrant color palettes and dramatic use of light and shadow employed by painters like Titian and Tintoretto profoundly impacted his developing style. Titian, in particular, is often cited as a likely teacher or significant influence, known for his mastery of color and psychological depth in portraiture. Tintoretto's dynamic compositions, elongated figures, and dramatic lighting also left an indelible mark on the young Cretan artist.

Following his Venetian period, El Greco moved to Rome around 1570. Here, he encountered the monumental art of the High Renaissance, particularly the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Michelangelo's powerful, muscular figures and expressive intensity, especially in the Sistine Chapel, resonated with El Greco, although he famously offered a critique of Michelangelo's draftsmanship. He also associated with intellectuals and artists in the circle of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, including the miniaturist Giulio Clovio, who became a friend and supporter, introducing him as a "rare talent" and a disciple of Titian. Rome exposed him further to Mannerism, a style characterized by artificial qualities, intellectual sophistication, and often elongated proportions, which aligned with his own developing tendencies.

The Toledo Years: Maturity and Unique Vision

Despite his talents, El Greco failed to secure major commissions in Rome. Perhaps finding the artistic environment dominated by the legacy of Michelangelo too competitive or restrictive, he made the pivotal decision to move to Spain around 1577. He initially hoped to gain the patronage of King Philip II, who was overseeing the decoration of the massive monastery-palace complex of El Escorial. While he did receive some royal commissions, his style did not fully align with the King's more austere tastes. Instead, El Greco found his true artistic home in the ancient city of Toledo.

Toledo, the former capital of Spain and its religious heart, provided a fertile ground for El Greco's unique genius. It was a city steeped in history, mysticism, and intense Catholic faith, particularly during the Counter-Reformation. This environment, combined with a sophisticated clientele of clergy, scholars, and local nobility, allowed El Greco's highly personal and spiritual style to flourish. He established a successful workshop, receiving numerous commissions for altarpieces, devotional paintings, and portraits. It was in Toledo that the fusion of his Byzantine heritage, Venetian color, Roman Mannerism, and intense personal spirituality coalesced into the unmistakable style for which he is known.

His arrival in Toledo was marked by significant commissions, most notably the high altarpiece for the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. This project included several major paintings, such as The Assumption of the Virgin, which immediately showcased his mature style: elongated figures reaching towards the heavens, vibrant, almost dissonant colors, and a powerful sense of spiritual ecstasy. This work established his reputation in the city and led to a steady stream of commissions that would occupy him for the rest of his life.

Masterworks and Signature Style

El Greco's oeuvre is dominated by religious subjects, reflecting the demands of his patrons and the spiritual fervor of Counter-Reformation Spain. However, he approached these familiar themes with an unprecedented emotional intensity and stylistic originality.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1577-1579): Originally painted for Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo and now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago, this work is a prime example of his early Spanish style. The Virgin Mary is depicted ascending to heaven, surrounded by angels, her elongated form and upward gaze conveying intense spirituality. The dynamic composition and the contrast between the earthly apostles below and the celestial vision above are characteristic of his dramatic approach. The use of bold, contrasting colors adds to the painting's emotional impact.

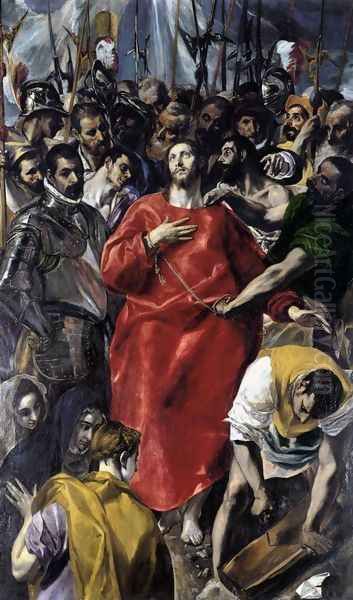

The Disrobing of Christ (El Espolio) (1577-1579): Commissioned for the sacristy of Toledo Cathedral shortly after his arrival, this painting became one of his most celebrated and controversial works. It depicts Christ being stripped of his robes before the Crucifixion, surrounded by a dense crowd. El Greco's focus is on Christ's serene acceptance amidst the turmoil, highlighted by the brilliant crimson of his robe. The compressed space, intense colors, and expressive figures created a powerful devotional image. However, the inclusion of figures deemed anachronistic (the Three Marys) and positioned higher than Christ led to a dispute and lawsuit with the Cathedral chapter over the painting's iconography and price, an early sign of the friction his unique vision could cause.

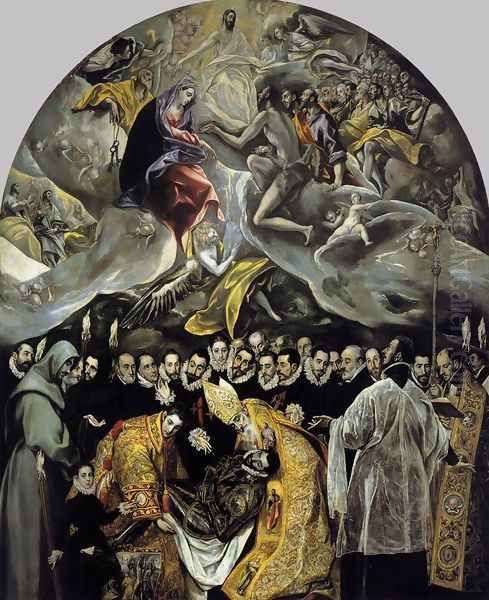

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586-1588): Widely considered El Greco's masterpiece, this monumental canvas remains in its original location, the Church of Santo Tomé in Toledo. It depicts a local legend: the miraculous appearance of Saint Stephen and Saint Augustine to inter the body of Don Gonzalo Ruíz de Toledo, Lord of Orgaz, a pious benefactor of the church. The painting is famously divided into two zones: the terrestrial realm below, rendered with striking realism in the portraits of contemporary Toledan figures witnessing the miracle, and the celestial realm above, where the Count's soul is received into heaven by Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Saint John the Baptist, depicted in El Greco's characteristic swirling, dematerialized style. This work masterfully combines portraiture, historical narrative, and mystical vision.

View of Toledo (c. 1596-1600): One of the most famous landscapes in Western art, this painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is a dramatic and interpretive depiction of the city El Greco called home. Rather than a precise topographical rendering, it is an expressive vision, with the city's landmarks rearranged under a stormy, tumultuous sky. The eerie lighting, dramatic contrasts, and swirling clouds imbue the scene with a powerful emotional and spiritual resonance, prefiguring the landscapes of Romanticism and Expressionism.

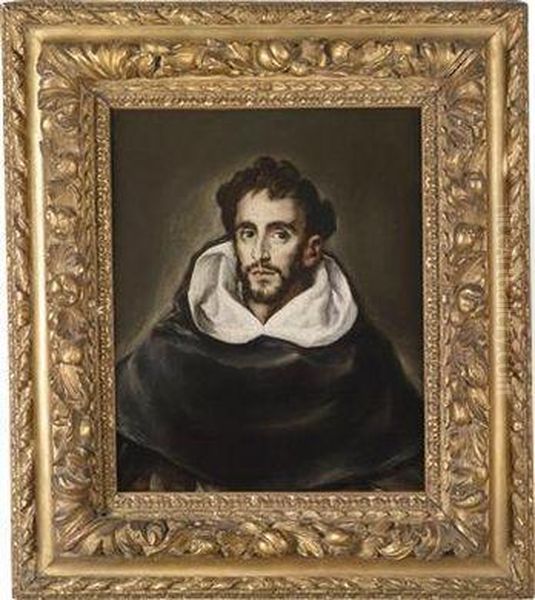

Portraits: While renowned for his religious works, El Greco was also a penetrating portraitist. He captured the psychological intensity and intellectual fervor of his sitters, often members of the Toledan elite. Notable examples include the portrait of his friend Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), the imposing Portrait of a Cardinal (likely Cardinal Tavera or Quiroga, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and portraits believed to be of his companion Jerónima de las Cuevas and his son Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli.

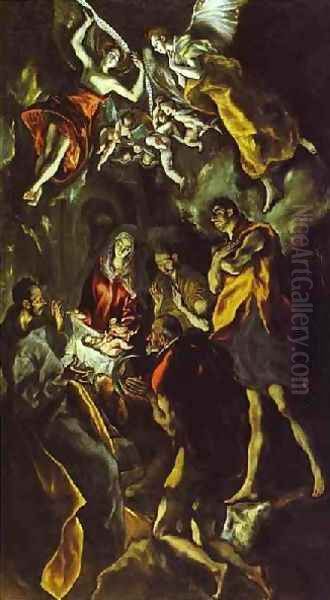

Late Works: In his final years, El Greco's style became even more abstract and spiritually intense. Works like The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1612-1614, Prado Museum, Madrid), intended for his own burial chapel, and The Opening of the Fifth Seal (c. 1608-1614, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) exhibit extreme elongation, flickering light, dissonant colors, and a focus on ecstatic spiritual experience that borders on the visionary. These late works are often seen as the culmination of his unique artistic journey.

Artistic Techniques and Innovations

El Greco's distinctive style is defined by several key characteristics that set him apart from his contemporaries and anticipated later artistic movements.

Elongation and Dematerialization: Perhaps the most recognizable feature of El Greco's art is the dramatic elongation of human figures. Fingers, necks, torsos, and limbs are stretched beyond natural proportions. This was not due to a visual defect like astigmatism, a theory long debunked, but a deliberate artistic choice. The elongation serves to dematerialize the figures, emphasizing their spiritual essence over their physical substance, lifting them towards the divine. It creates a sense of aspiration, ecstasy, and otherworldly grace, particularly fitting for his religious subjects.

Color and Light: El Greco employed color not for naturalistic representation but for emotional and symbolic effect. He used vibrant, often acidic hues – sharp yellows, greens, blues, and reds – juxtaposed in startling combinations. His palette moved away from the warmer tones of his Venetian training towards cooler, more ethereal colors. Light in his paintings is equally dramatic and non-naturalistic. Often described as cold or flickering, it emanates from unseen sources, creating stark contrasts (chiaroscuro) that highlight spiritual drama and dematerialize forms. This use of color and light contributes significantly to the mystical and visionary quality of his work.

Composition and Space: El Greco often rejected the rational, ordered perspective systems of the High Renaissance. His compositions are frequently dynamic, swirling, and densely packed with figures. Space can be ambiguous, compressed, or vertiginously deep, drawing the viewer into the spiritual vortex of the scene. Figures overlap and intertwine, creating complex rhythms and patterns that enhance the emotional intensity. This departure from classical compositional norms aligns him with Mannerist tendencies but pushes beyond them into a realm of personal expression.

El Greco and His Contemporaries

While deeply influenced by Italian masters like Titian, Tintoretto, Michelangelo, and perhaps Jacopo Bassano, El Greco's relationship with his Spanish contemporaries was complex. He arrived in Spain when artists like Luis de Morales, known for his intense devotional panels, and Juan Fernández Navarrete, a favorite of Philip II, were prominent. However, El Greco's style remained largely distinct from the prevailing Spanish trends, which often emphasized a more sober realism or followed Italian models more closely.

There is no documented evidence of direct personal interaction or collaboration between El Greco and the next generation of great Spanish Baroque painters, Diego Velázquez and Peter Paul Rubens (a Fleming who spent time in Spain). El Greco died in 1614, when Velázquez was still a teenager. While Velázquez undoubtedly saw El Greco's works during his visits to Toledo and may have drawn inspiration from their intensity and painterly freedom, their artistic aims and styles differed significantly. Velázquez became renowned for his courtly portraits and mastery of realism. Rubens, who visited Spain earlier, reportedly admired El Greco, calling him a "great painter," but his own exuberant Baroque style, influenced by Venetian color and classical forms, followed a different trajectory. El Greco's immediate influence in Spain was primarily limited to his son, Jorge Manuel, and a few workshop assistants like Luis Tristán.

Controversies and Reception

Despite his success in securing commissions in Toledo, El Greco's highly individualistic style was not universally embraced during his lifetime or in the centuries immediately following his death. His deviations from naturalism, his sometimes jarring colors, and the intense emotionalism of his work were often perceived as eccentric or even bizarre. The lawsuit concerning El Espolio highlights the potential for conflict when his artistic vision clashed with conventional expectations.

Financial difficulties also plagued him, particularly in his later years. Records indicate disputes over payments and suggest he lived beyond his means, leading to significant debt and possibly even bankruptcy towards the end of his life. This suggests that while respected within certain circles in Toledo, he may not have achieved the widespread fame or financial security of some other leading artists of the era.

After his death, El Greco's reputation faded. During the Baroque period, dominated by the realism of Velázquez, Zurbarán, and Murillo, and later during the Neoclassical era with its emphasis on order and clarity, his passionate and distorted style fell out of favor. He was often dismissed as an eccentric curiosity, his unique qualities misunderstood or unappreciated.

Unanswered Questions and Scholarly Debates

Despite extensive research, aspects of El Greco's life remain enigmatic, fueling ongoing scholarly discussion.

Name and Identity: While Doménikos Theotokópoulos is accepted as his birth name, the exact form he used in Italy (sometimes signing as 'Domenico') and the nuances of his identity as a Greek artist working in Italy and Spain continue to be explored. The persistence of the nickname "El Greco" itself speaks to how his origins remained a defining characteristic.

Marital Status: El Greco never married Jerónima de las Cuevas, the mother of his only known son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli (born 1578). The reasons remain unclear – perhaps due to stipulations in his patrons' circles or personal choice. Whether he had a wife before leaving Crete or during his time in Italy is purely speculative, as no records have been found.

Late Life Finances: The precise nature and extent of his financial troubles in later life are still debated. While evidence points to debt, the image of him dying in poverty might be exaggerated. He maintained a large workshop and lived in considerable style for much of his Toledan period.

Cause of Death: El Greco died somewhat suddenly in Toledo on April 7, 1614, while reportedly working on a commission for the Hospital Tavera. The specific cause of his death at the age of 73 is not recorded, leaving it as another minor mystery.

Artistic Intent: While his deep Catholic faith is evident, the precise theological or philosophical ideas underpinning his unique stylistic choices remain a subject of interpretation. Was his style purely a reflection of personal piety, influenced by Spanish mysticism (like that of Saint Teresa of Ávila or Saint John of the Cross), or a conscious artistic strategy employing Mannerist devices for heightened effect? The answer likely involves a combination of these factors.

Legacy and Influence on Modern Art

El Greco's true resurgence began in the mid-19th century, fueled by the Romantic fascination with individualism and emotion. Artists and critics began to rediscover his work, appreciating its expressive power and originality. By the early 20th century, he was hailed as a visionary genius, a precursor to modern art movements.

His impact on Expressionism is undeniable. Artists in Germany and Austria, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Oskar Kokoschka, and Egon Schiele, saw in El Greco a kindred spirit who prioritized emotional expression over naturalistic representation. His distorted figures, intense colors, and dramatic compositions provided a powerful historical precedent for their own explorations of psychological states and spiritual angst. Edvard Munch, the Norwegian pioneer of Expressionism, also studied El Greco's work.

The pioneers of Cubism, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, were also profoundly influenced by El Greco, particularly through the structural analysis championed by Paul Cézanne. Picasso, during his Blue and early Cubist periods, explicitly referenced El Greco's elongated forms and fragmented spaces. The Opening of the Fifth Seal is often cited as a direct inspiration for Picasso's seminal work, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Both Picasso and Braque admired El Greco's departure from conventional perspective and his ability to construct form through color and light.

Beyond these movements, El Greco's influence can be seen in the work of various modern artists. Édouard Manet was an early admirer who traveled to Spain to study his work. Artists like Chaïm Soutine found validation for their own expressive brushwork and distorted forms in El Greco's paintings. Even abstract artists have acknowledged his innovative use of color and composition. The Finnish modernist Helene Schjerfbeck also drew inspiration from his work. El Greco's journey from obscurity to becoming a foundational figure for modern art underscores the enduring power of his unique vision.

Major Collections

Today, El Greco's works are treasured in major museums and collections around the world, although Spain, particularly Toledo and Madrid, retains the richest holdings.

Prado Museum, Madrid: Holds a large and significant collection, including The Adoration of the Shepherds, The Holy Trinity, The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest, and numerous portraits and apostle series.

El Greco Museum, Toledo: Located in the former Jewish Quarter where the artist lived, this museum houses important works like View and Plan of Toledo, portraits, and apostle series, offering context to his life in the city.

Church of Santo Tomé, Toledo: Home to his masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz.

Toledo Cathedral: Contains The Disrobing of Christ (El Espolio) in its original setting.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Features key works such as View of Toledo, Portrait of a Cardinal, and The Opening of the Fifth Seal.

Art Institute of Chicago: Houses The Assumption of the Virgin and Saint Martin and the Beggar.

National Gallery, London: Holds important works like Christ Driving the Traders from the Temple and The Agony in the Garden.

Louvre Museum, Paris: Features works including Christ on the Cross Adored by Donors.

The Frick Collection, New York: Contains notable portraits and religious scenes like Saint Jerome and Vincenzo Anastagi.

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg: Owns the celebrated apostle pairing Saints Peter and Paul.

Conclusion

Doménikos Theotokópoulos, El Greco, remains a towering figure in art history, a unique bridge between the Byzantine traditions of his homeland, the innovations of the Italian Renaissance and Mannerism, and the intense spirituality of Counter-Reformation Spain. His unwillingness to compromise his personal vision resulted in a body of work characterized by dramatic elongation, vibrant, often dissonant color, flickering light, and profound emotional intensity. Misunderstood and largely forgotten for centuries, his rediscovery cemented his status as not only a master of the Spanish school but also a prophetic forerunner of modern art, whose influence continues to resonate with artists and viewers captivated by his passionate and visionary depictions of the human and the divine. His art challenges, inspires, and transports, securing his place as one of the most original and compelling painters of all time.