Louis Michel Eilshemius stands as one of the more enigmatic and unconventional figures in the history of American art. Born into privilege yet spending much of his career in obscurity, his work traversed traditional landscapes influenced by European masters before veering into a highly personal, often fantastical realm that bewildered many contemporaries but later captivated the avant-garde. His life, marked by early promise, profound creativity across multiple disciplines, and eventual isolation, offers a fascinating study of artistic independence and the unpredictable nature of recognition.

Early Life and Formative Years

Louis Michel Eilshemius was born on February 4, 1864, in Newark, New Jersey, into a prosperous family. His early life was cosmopolitan; he received his initial education abroad, studying in Geneva, Switzerland, and Dresden, Germany. This European exposure likely provided a broad cultural foundation before his return to the United States in 1881.

Upon returning, Eilshemius enrolled at Cornell University. Interestingly, his initial field of study was not art, but rather agriculture and related sciences. Even during this period, however, his inclinations towards the arts, particularly poetry and painting, began to surface, hinting at the multifaceted creative drive that would define his later life.

Recognizing his true calling lay in the visual arts, Eilshemius eventually shifted his focus. He sought formal training, first studying at the Art Students League of New York. This institution was a vital hub for aspiring American artists, providing a space to hone technical skills and engage with contemporary artistic currents.

Seeking further refinement and exposure to European traditions, Eilshemius traveled to Paris between 1886 and 1887. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, a renowned independent art school that attracted students from around the world. During his time there, he studied under the prominent academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau, absorbing the rigorous techniques and classical ideals prevalent in French academic art of the period.

The Influence of Tradition: Early Artistic Pursuits

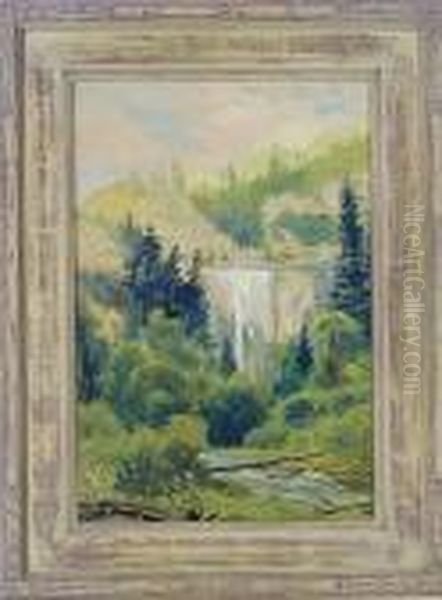

Eilshemius's early artistic output clearly reflects the influences he absorbed during his training and his appreciation for established landscape traditions. His initial works, primarily landscapes, show a strong affinity for the French Barbizon School painters, known for their realistic yet poetic depictions of rural life and nature. The influence of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a leading figure of the Barbizon School, is particularly evident in the soft, atmospheric quality and tranquil moods of Eilshemius's early canvases.

Alongside the Barbizon influence, Eilshemius drew inspiration from prominent American landscape painters. George Inness, whose work evolved from the Hudson River School towards a more Tonalist and spiritually infused style, left a noticeable mark on Eilshemius's handling of light and atmosphere. The quiet, introspective, and often mystical qualities found in the works of Albert Pinkham Ryder, another key figure in American Romantic painting, also resonated with Eilshemius's developing sensibilities.

During this phase, Eilshemius demonstrated a considerable understanding of light, shadow, and the nuances of the natural world. His paintings often captured serene, pastoral scenes, imbued with a romantic sensibility. Works like Adirondacks: Fishing Bridge (1897) exemplify this period, showcasing his skill in rendering the subtle beauty of the American landscape with a delicate touch and sensitivity to mood, reflecting the prevailing tastes for idyllic and contemplative natural scenes.

Forging an Independent Path: Evolution Towards a Unique Vision

While Eilshemius's early work was grounded in established traditions, his artistic journey took a distinct turn towards a more idiosyncratic and personal style. His travels, including experiences in Europe and possibly North Africa (though specifics are less documented in the provided sources), seemed to broaden his imaginative horizons and encourage a departure from purely naturalistic representation.

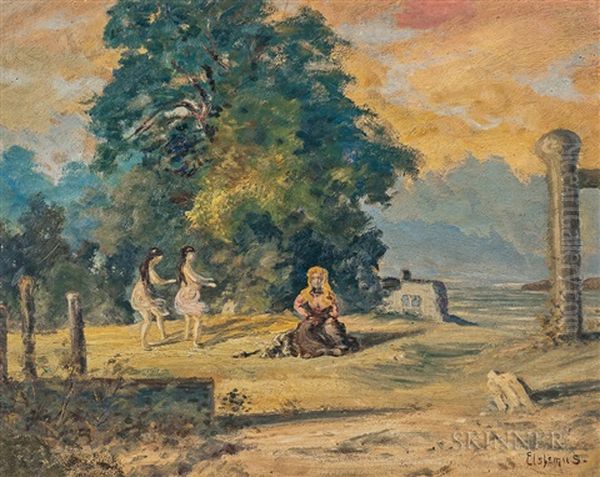

His style gradually became more individualistic, incorporating elements that could be described as surreal or fantastical. The tranquil landscapes began to give way to scenes charged with greater emotional intensity and populated by unexpected figures. A key feature of this evolution was his increasing focus on the nude figure, often depicted in outdoor settings. These nudes, sometimes ethereal, sometimes overtly sensual, were rendered in a manner that defied academic convention and often courted controversy among the public and critics of the time.

This shift is visible in works like Landscape with Approaching Storm (also cited as Stormy Landscape) from around 1890. Here, the dramatic potential of nature is heightened through expressive brushwork and a more charged atmosphere than seen in his earlier, calmer landscapes. Later works, such as The Rejected Suitor (1915), delve further into narrative and psychological drama, employing exaggerated forms and colors to convey complex emotional states. His art became a vehicle for exploring inner worlds, fantasies, and anxieties, moving far beyond the objective depiction of external reality.

A Pivotal Encounter: Marcel Duchamp and the Avant-Garde

Despite his prolific output and developing unique style, Eilshemius labored for years without significant recognition from the established art world. His breakthrough moment arrived somewhat unexpectedly in 1917, thanks to the discerning eye of the influential French artist Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp, a central figure in Dadaism and a key proponent of avant-garde art in America, encountered Eilshemius's work at the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

The Society of Independent Artists was founded on the principle of "no jury, no prizes," allowing any artist to exhibit upon payment of a small fee. It was here that Eilshemius showed works, including one possibly titled Supplication, which caught Duchamp's attention. Duchamp was immediately struck by the raw, unconventional power and originality of Eilshemius's vision, seeing past the perceived technical eccentricities that may have deterred others.

Duchamp became an ardent champion of Eilshemius. He not only purchased the artist's work but also played a crucial role in bringing it to wider notice. Collaborating with Katherine S. Dreier, another major patron of modern art and co-founder of the Société Anonyme, Inc., Duchamp organized Eilshemius's first significant solo exhibitions. These took place at the Société Anonyme's gallery in New York in 1920 and again in 1924.

The Société Anonyme was dedicated to promoting modern and avant-garde art in America, making it the perfect platform for an artist as unconventional as Eilshemius. These exhibitions, backed by figures of Duchamp's and Dreier's stature, thrust Eilshemius into the spotlight, generating considerable discussion and marking a turning point in his career, albeit one that would prove relatively short-lived in terms of mainstream acceptance during his lifetime. The attention garnered even reportedly caught the notice of artists like Henri Matisse.

Navigating the Art World: Connections and Isolation

The support from Marcel Duchamp and Katherine S. Dreier provided Eilshemius with invaluable connections to the burgeoning modernist art scene in New York. Through the Société Anonyme, he was associated with other avant-garde artists who were challenging traditional norms. Figures like Joseph Stella, known for his Futurist-inspired depictions of urban America, and Abraham Walkowitz, recognized for his modernist drawings and paintings, were also part of this milieu, and the Société Anonyme facilitated Eilshemius's exposure within these progressive circles.

Despite this crucial support network, Eilshemius remained a largely peripheral figure within the broader art community. His personality reportedly played a significant role in his relative isolation. Described as eccentric, highly self-absorbed, and extremely sensitive to criticism, he often alienated potential supporters and peers. His tendency towards self-promotion, sometimes taking grandiose forms (he famously bestowed upon himself numerous lofty titles), could be off-putting.

While the Duchamp-backed exhibitions brought him a flurry of attention in the early 1920s, this recognition did not translate into sustained critical acclaim or widespread patronage. He remained an outsider, admired by a select few within the avant-garde but largely misunderstood or dismissed by the mainstream art establishment and the public. This complex dynamic – moments of significant recognition intertwined with persistent marginalization – characterized much of his interaction with the art world.

Unconventional Methods and Materials

Part of what made Eilshemius's work distinct, and perhaps contributed to his marginalization, was his unconventional approach to materials and techniques. While trained in traditional methods, he often deviated from academic standards in his mature work. His brushwork could be fluid and expressive, sometimes appearing unrefined or "naive" to conventionally trained eyes.

Furthermore, Eilshemius frequently painted on supports other than traditional canvas. He was known to use cardboard, fiberboard, and even everyday objects like cigar box lids or smoke box covers as surfaces for his paintings. This use of non-traditional materials might have stemmed partly from financial necessity at times, but it also aligns with a certain modernist impulse to break down hierarchies between "high" art materials and everyday objects, although Eilshemius himself may not have theorized it in those terms.

This technical idiosyncrasy, combined with his often fantastical subject matter and unique rendering of form and space, led some critics to label his work as "primitive" or "naive." While perhaps intended dismissively by some, this label also points to the untutored, direct, and highly personal quality that Duchamp and other admirers found so compelling. His methods were intrinsically linked to his singular artistic vision, prioritizing expressive force over academic polish.

The Renaissance Man Persona

Eilshemius's creative energies were not confined solely to painting. He was a man of diverse talents and ambitions, cultivating the persona of a polymath or "Renaissance Man." Alongside his prolific output as a painter, he was also a writer, composer, and self-proclaimed philosopher.

He wrote extensively, producing volumes of poetry, letters, and pamphlets often characterized by the same idiosyncratic and sometimes grandiose style found in his visual art and public pronouncements. His writings explored various themes, often reflecting his personal philosophies, romantic inclinations, and frustrations with his lack of recognition.

Music was another significant pursuit. He composed musical pieces, further demonstrating the breadth of his creative interests. This multifaceted creativity suggests an artist driven by a powerful need for self-expression across different mediums. While his paintings remain his most enduring legacy, understanding his activities as a poet, musician, and thinker provides a fuller picture of his complex personality and his ambition to be recognized as a genius of universal talents. His work across disciplines often shared a dramatic, intensely personal, and sometimes eccentric quality.

Waning Years and Artistic Silence

Despite the flurry of attention brought by Duchamp's advocacy in the late 1910s and early 1920s, Eilshemius's period of active engagement with the art world was relatively brief. Around 1921, a pivotal year, he largely ceased painting. The reasons for this withdrawal appear multifaceted, stemming from a combination of factors mentioned in historical accounts.

Persistent lack of widespread recognition and financial success likely contributed to disillusionment. Coupled with this were reported health problems, which may have physically impeded his ability to work. Furthermore, his documented eccentricities and perhaps deteriorating social skills might have led to increased isolation and withdrawal from public life and the demands of an artistic career.

After abandoning painting, Eilshemius lived in relative seclusion in the family home in New York City. While his work began to experience a slow rediscovery by critics and collectors in the 1930s, he himself remained largely detached from the art scene. His final years were marked by declining health. Louis Michel Eilshemius died on December 29, 1941, reportedly from complications of pneumonia.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Although Louis Michel Eilshemius experienced limited success and recognition during his active painting years, his artistic legacy underwent a significant reappraisal, particularly from the 1930s onwards and accelerating after his death. The very qualities that made him an outsider during his lifetime—his unique blend of romanticism, fantasy, and psychological intensity, rendered with unconventional techniques—came to be appreciated by later generations of artists, critics, and collectors.

Key figures played a role in this posthumous elevation. Collectors like Duncan Phillips, founder of The Phillips Collection, recognized the unique merit of Eilshemius's work and acquired pieces for his museum. Roy Neuberger was another significant collector who amassed a substantial number of Eilshemius paintings, later donating many to the Neuberger Museum of Art, ensuring their preservation and public access.

Eilshemius's distinctive style and uncompromising individuality have also resonated with later artists. For instance, the contemporary American artist Ed Ruscha has acknowledged an affinity for Eilshemius's work, suggesting a lasting influence that transcends stylistic periods. The Swiss contemporary artist Ugo Rondinone has also shown a deep interest, curating exhibitions that place Eilshemius's work in dialogue with his own, highlighting the enduring relevance of the older artist's singular vision.

Today, Eilshemius is regarded as an important, if eccentric, figure in early 20th-century American art. He is seen as a precursor to certain aspects of Surrealism and Expressionism in America, valued for his imaginative power and his departure from academic norms. His journey from obscurity to posthumous recognition underscores the often-unpredictable path of artistic reputations.

Eilshemius in Collections and Exhibitions

Reflecting his eventual recognition, works by Louis Michel Eilshemius are now held in the collections of major art institutions across the United States. Prominent museums housing his paintings include the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.

Specific works mentioned in auction records and collection histories further illustrate his presence. His painting Hula Dancers (c. 1908-1913) was noted as being deaccessioned by the Saint Louis Art Museum via a Skinner auction to benefit its acquisitions fund. Another work, Approaching Storm (early 1900s), is held by the Columbus Museum of Art (formerly Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts). The Neuberger Museum of Art at Purchase College, SUNY, holds a significant number thanks to Roy Neuberger's donations.

His work continues to be featured in exhibitions. A notable recent example is the 2023-2024 exhibition at The Phillips Collection, which paired Eilshemius's paintings with works by the contemporary artist Ugo Rondinone, exploring affinities across generations. Such exhibitions demonstrate the ongoing scholarly and curatorial interest in reassessing Eilshemius's contribution to American art history and introducing his unique vision to new audiences.

Conclusion: An Enduring Original

Louis Michel Eilshemius remains a fascinating and complex figure in American art history. His journey took him from a privileged upbringing and traditional training under masters like Bouguereau to the development of a deeply personal and often fantastical style influenced by Romantic painters like Inness and Ryder, yet ultimately unlike anyone else's. Initially ignored or ridiculed by many, his work found crucial support from avant-garde figures like Marcel Duchamp and Katherine S. Dreier, leading to brief moments of recognition.

Though he ceased painting relatively early in his potential career and lived out his later years in obscurity, his artistic output—characterized by dreamlike landscapes, evocative nudes, dramatic narratives, and unconventional techniques—has earned him a lasting, if somewhat cult, following. His rediscovery and the subsequent appreciation by collectors, museums, and later artists like Ed Ruscha and Ugo Rondinone confirm his status as a true American original. Eilshemius's legacy lies in his unwavering commitment to his singular vision, creating a body of work that continues to intrigue and resonate with its unique blend of lyricism, mystery, and raw emotional power.