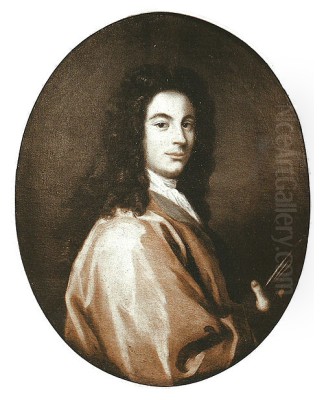

Antonio Balestra stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Italian art during the transition from the High Baroque to the early Rococo period. Born in Verona in 1666 and passing away in the same city in 1740, Balestra carved a distinct niche for himself as both a painter and an etcher. His artistic identity is characterized by a refined blend of late Baroque Classicism, deeply influenced by his time in Rome, with the rich chromatic traditions of Venetian painting. This synthesis brought a renewed sense of elegance and clarity to Northern Italian art, establishing Balestra as a pivotal artist of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Verona and Venice

Antonio Balestra's journey into the world of art was not immediate. His initial education in Verona was grounded in the humanities, focusing on literature and rhetoric. However, his innate inclination towards the visual arts eventually led him to pursue painting. Verona, with its own artistic heritage, provided the initial backdrop, but the burgeoning artist soon sought broader horizons.

In 1687, Balestra made the crucial move to Venice, the vibrant heart of colorito (emphasis on color and brushwork) in Italian painting. There, he entered the studio of Antonio Bellucci, a respected painter whose work exemplified the decorative grace of the Venetian school. Under Bellucci's guidance, Balestra honed his technical skills, absorbing the Venetian emphasis on rich palettes, dynamic compositions, and the expressive potential of paint application. This period was fundamental in shaping his lifelong appreciation for color and light.

Roman Sojourn and the Embrace of Classicism

Seeking to deepen his understanding of form and composition, Balestra traveled to Rome, the center of disegno (emphasis on drawing and design) and the bastion of the classical tradition. This move proved transformative. He joined the prestigious workshop of Carlo Maratta (also spelled Maratti), the undisputed leader of the Roman school in the later 17th century. Maratta was a proponent of a restrained, elegant Baroque Classicism that looked back to the High Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael, and the Bolognese school led by Annibale Carracci.

Under Maratta's tutelage, Balestra immersed himself in the study of classical principles: clarity of narrative, balanced composition, idealized human forms, and controlled emotion. He studied the works of Raphael and absorbed the lessons of Carracci and his followers, such as Domenichino, whose clarity and grace resonated with Maratta's own style. This Roman experience instilled in Balestra a profound respect for drawing, structure, and the grand manner of history painting.

A significant milestone during his Roman period was winning the first prize from the prestigious Accademia di San Luca in 1694. His winning submission, the dynamic and skillfully composed Fall of the Giants, showcased his mastery of anatomy, complex figural arrangement, and the dramatic potential of classical themes, signaling his arrival as a formidable talent on the Italian art scene.

Mature Style: A Synthesis of Traditions

Returning from Rome, Balestra did not simply abandon his Venetian roots for Roman classicism, nor vice versa. Instead, his mature style represents a sophisticated fusion of these two powerful, often competing, Italian artistic traditions. He successfully integrated the structural clarity, precise drawing, and idealized forms learned under Maratta in Rome with the luminous color, atmospheric effects, and painterly richness acquired in Venice.

His paintings are characterized by a distinct elegance and refinement. Figures are often gracefully posed, drapery falls in clear, understandable folds, and compositions are carefully balanced, avoiding the extreme turbulence of some High Baroque masters. Yet, his work is rarely cold or overly academic. He infused his classical structures with a gentle light and a palette that, while often featuring soft, harmonious tones, retained a Venetian sensitivity to color relationships and atmospheric depth. His brushwork, typically smooth and controlled, could also exhibit a subtle vibrancy.

This unique blend allowed Balestra to create works that were both intellectually satisfying in their clarity and emotionally appealing in their gentle grace and chromatic warmth. He navigated a path between the more exuberant Baroque styles and the emerging lighter sensibilities of the Rococo, maintaining a dignified classicism throughout his career.

Major Works and Themes

Antonio Balestra's oeuvre primarily consists of religious and historical subjects, catering to the demands of church commissions and private patrons seeking large-scale narrative paintings. His works adorned churches and palaces across Northern Italy and beyond.

His prize-winning Fall of the Giants (1694) remains a key example of his early mastery of complex, multi-figure composition learned in Rome. Throughout his career, he produced numerous altarpieces. Works like The Virgin Appearing to St. Gregory and St. Andrew demonstrate his ability to handle traditional religious iconography with clarity and devotional sensitivity. The Madonna and Child theme appears recurrently, often treated with a characteristic tenderness and grace.

Another notable work is the Adoration of the Shepherds, painted for the Church of San Zaccaria in Venice. This painting, located at the end of the south aisle, showcases his ability to infuse a traditional scene with gentle light and serene emotion, fitting harmoniously within the rich artistic context of the Venetian church. Other significant religious works include The Saints Sebastian, Irene and Lucia, depicting martyrdom with pathos but avoiding excessive gore, focusing instead on piety and divine acceptance.

His Death of Abel, known to have been exhibited, exemplifies his skill in depicting dramatic biblical narratives, focusing on the emotional impact and the classical rendering of the human form. Balestra also undertook secular commissions, including historical and mythological scenes, attracting patrons not only from Italy but also from abroad, such as the Elector of Mainz, indicating his international reputation.

Return to Verona and Teaching Legacy

Around 1718, Antonio Balestra returned permanently to his native Verona. By this time, he was a highly respected master, and his return significantly boosted the city's artistic life. He established a prominent workshop and school, becoming a central figure in the Veronese art scene for the remainder of his life.

His role as a teacher was crucial to his legacy. Balestra was not only a prolific painter but also a dedicated educator who transmitted his principles of combining Roman design with Venetian color to a new generation. He influenced many younger artists, shaping the course of painting in Verona and the Veneto region in the first half of the 18th century.

Among his notable pupils and followers were Pietro Rotari, who later achieved international fame as a portraitist, particularly at the Russian court, and Giambettino Cignaroli, another leading figure in Veronese painting who continued a refined, classicizing tradition. The influence of Balestra's balanced and elegant style can be seen in their work and that of others who passed through his studio or fell under his influence, such as Gaspare Diziani, whose Venetian works show some affinities, and the aforementioned Barone Cavalcabò. Balestra's teaching ensured the continuation of a strong classical current in Northern Italian art.

Artistic Context and Contemporaries

Antonio Balestra operated during a fascinating period of transition in Italian art. The High Baroque, dominated by figures like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona in Rome, was evolving. Balestra's teacher, Carlo Maratta, represented a more classical, restrained reaction to the High Baroque's exuberance. Balestra inherited this classicism but tempered it with his Venetian experience.

In Venice, he was contemporary with major figures who were pushing Venetian art towards the Rococo, such as the brilliant Sebastiano Ricci, known for his light-filled, dynamic compositions, and Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, master of dramatic chiaroscuro and expressive realism. Later in Balestra's life, the great Giovanni Battista Tiepolo would emerge, representing the pinnacle of Venetian decorative painting. Balestra's more sober and classical style offered a counterpoint to these trends.

In Rome, besides Maratta, artists like Benedetto Luti were active. In Bologna, the classical tradition stemming from the Carracci continued, with contemporaries like Marcantonio Franceschini (whom Balestra reportedly influenced) and Donato Creti maintaining a focus on clarity and refined drawing. Balestra's work can be seen as part of a broader pan-Italian dialogue involving these various regional schools and stylistic tendencies, bridging the late 17th-century classicism of Maratta with the emerging aesthetics of the 18th century. He was influenced by predecessors like Raphael and Annibale Carracci, learned directly from Bellucci and Maratta, and interacted with or influenced contemporaries and students like Ricci, Franceschini, Rotari, and Cignaroli.

Influence and Reputation

Antonio Balestra's influence was most profoundly felt in Northern Italy, particularly in Verona and the Veneto. His successful synthesis of Roman disegno and Venetian colore provided a compelling model for artists seeking elegance, clarity, and chromatic appeal. He helped to sustain a classical tradition in the region, offering an alternative to the more purely decorative or dramatically intense styles prevalent elsewhere.

His reputation during his lifetime was considerable, evidenced by prestigious commissions, his prize from the Accademia di San Luca, and international patronage. He was regarded as a leading master in Verona, revitalizing the local school through his work and teaching. His influence extended through his numerous pupils, ensuring that his stylistic principles permeated the art of the region for decades.

While perhaps overshadowed in broader art historical narratives by the more revolutionary figures of the Baroque or the dazzling stars of the Venetian Rococo like Tiepolo, Balestra remains a crucial figure for understanding the nuances of Italian painting in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. He represents a significant strand of late Baroque classicism, enriched by Venetian sensibilities, and played a vital role in regional artistic developments.

The San Zaccaria Connection (Corrected)

Historical sources sometimes create confusion regarding artists working in the same location across different centuries. The Church of San Zaccaria in Venice is richly decorated with artworks spanning several periods. Both Antonio Balestra and the Early Renaissance master Andrea del Castagno contributed works to this church, but they were separated by over two centuries.

Andrea del Castagno, along with Francesco da Faenza, painted frescoes in the vault of the San Tarasio Chapel within San Zaccaria around 1442. These frescoes, depicting saints and God the Father, are important examples of Florentine Renaissance art finding its way to Venice. Castagno died in 1457.

Antonio Balestra worked in San Zaccaria much later, likely in the early 18th century. His contribution, as mentioned earlier, is the altarpiece Adoration of the Shepherds. There was absolutely no possibility of interaction or collaboration between Balestra and Castagno; they belong to entirely different artistic eras – the Early Renaissance and the Late Baroque, respectively. Their presence in the same church complex highlights the long and layered history of artistic patronage at San Zaccaria. Similarly, Giovanni d'Alemagna, another 15th-century artist active in Venice, was not a contemporary of Balestra.

Anecdotes and Controversies

Despite his prominence, the historical record, as reflected in the available summaries, does not seem rich in specific personal anecdotes or details of major controversies involving Antonio Balestra. His career appears to have been one of steady work, teaching, and respected achievement within the established artistic systems of Venice, Rome, and Verona. Unlike some more tempestuous figures in art history, Balestra seems to have maintained a professional path, focused on fulfilling commissions and developing his refined artistic style. The lack of recorded scandal or major dispute suggests a life dedicated primarily to his craft and the running of his successful studio. Likewise, specific documented criticisms of his style from his contemporaries are not readily highlighted, suggesting general acceptance within the classicizing mainstream of his time.

Scholarly Assessment and Legacy

Modern art historical scholarship recognizes Antonio Balestra as an important artist within the context of late Baroque Italy. He is praised for his technical skill, the elegance of his compositions, and particularly for his successful integration of Central Italian classicism with Venetian color. Scholars like L. Ghio, E. Baccheschi (authors of a monograph on Balestra), and Ugo Ruggini (who published documented works) have contributed to the understanding of his career and oeuvre.

His work is seen as representing a significant alternative to the more flamboyant aspects of Baroque and Rococo art, upholding principles of clarity, grace, and decorum. His role as a teacher in Verona is also acknowledged as crucial for the development of 18th-century painting in the Veneto. His paintings are held in various museums and collections, including the Corsini Galleries in Rome and Florence, and continue to be studied as exemplars of the refined classicizing currents in late Baroque Italian art.

Conclusion

Antonio Balestra navigated the complex artistic currents of the late Baroque and early Rococo periods with remarkable skill and consistency. His ability to forge a personal style that harmonized the linear precision and idealized forms of Roman classicism with the rich color and light of Venice resulted in works of enduring elegance and appeal. As a painter and influential teacher, he left an indelible mark on the art of Verona and Northern Italy, ensuring his place as a distinguished master whose contributions continue to be appreciated for their refinement, technical mastery, and graceful synthesis of major Italian artistic traditions. His legacy lies not only in his beautiful canvases but also in the generation of artists he inspired.