Introduction: An Heir to Venetian Tradition

Antonio Diziani, born in the vibrant artistic hub of Venice in 1737 and passing away in 1797, stands as a notable figure in the twilight years of the celebrated Venetian school of painting. Primarily recognized for his enchanting landscape paintings, Diziani carved a niche for himself within a city already brimming with artistic giants. He was the son of the esteemed painter and stage designer Gaspare Diziani, inheriting a rich artistic legacy that he skillfully adapted to his own predilections, focusing predominantly on the depiction of idyllic nature and rustic life. His work captures the Rococo sensibility prevalent in 18th-century Venice, characterized by charm, elegance, and a certain lightness of touch, particularly evident in his favoured pastoral scenes.

Antonio Diziani's artistic journey unfolded during a period when Venice, though politically declining, was experiencing a final, brilliant flourish in the arts. Landscape painting, in particular, gained significant popularity, catering to the tastes of local patrons and the increasing number of affluent Grand Tourists visiting the city. Diziani emerged as a significant contributor to this genre, developing a style marked by lively execution and a keen eye for atmospheric detail, ensuring his place among the respected painters of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Venice

Born into an artistic family in Venice, Antonio Diziani's path into the world of painting seems almost preordained. His father, Gaspare Diziani (1689–1767), was a prominent figure in the Venetian art scene, known for his historical paintings, religious works, and notably, his contributions to theatrical set design. Gaspare himself had trained under respected masters like Gregorio Lazzarini and, more significantly, Sebastiano Ricci, absorbing the dynamic compositions and luminous colour palettes characteristic of the late Baroque and emerging Rococo styles. This environment undoubtedly provided Antonio with his initial exposure to artistic techniques and the bustling world of Venetian workshops.

While specific details of Antonio's formal training are scarce, it is almost certain that he received his foundational instruction from his father. Gaspare's workshop would have been a hive of activity, offering the young Antonio ample opportunity to learn drawing, composition, and paint handling. He would have observed his father's methods, perhaps assisting on larger commissions, and gradually developing his own skills. The influence of Gaspare's style, particularly his fluid brushwork and decorative sense, can be discerned in Antonio's early works, though the son would soon gravitate towards a different primary subject matter.

Unlike his father, whose oeuvre encompassed a broader range of genres, Antonio developed a strong preference for landscape painting. This specialization likely occurred relatively early in his career, possibly influenced by the growing market demand for such scenes and by the work of other successful landscape painters active in Venice during his formative years. His father's connections within the Venetian art community would have also provided Antonio access to influential figures and potential patrons, facilitating the launch of his independent career.

The Context: 18th-Century Venetian Landscape Painting

Antonio Diziani's career unfolded against the backdrop of a thriving landscape painting tradition in 18th-century Venice. This era saw the genre flourish, moving beyond mere backdrops for historical or religious scenes to become a subject in its own right. Two main currents dominated: the topographical veduta (view painting) and the idealized or pastoral landscape. The veduta, famously mastered by artists like Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) and later Francesco Guardi, focused on precise, recognizable depictions of Venetian cityscapes and landmarks, appealing to tourists seeking souvenirs of their travels.

The second current, to which Antonio Diziani belonged, focused on idealized rural scenes, often inspired by the landscapes of the Venetian mainland (Terraferma) or evoking classical Arcadian ideals. This tradition drew inspiration from earlier masters but found fresh expression in the 18th century through painters like Marco Ricci, whose atmospheric and sometimes tempestuous landscapes were highly influential. Marco Ricci, Sebastiano Ricci's nephew, was a pivotal figure in establishing landscape as an independent genre in Venice.

Other key figures shaping the pastoral landscape style contemporary to or slightly preceding Antonio Diziani were Francesco Zuccarelli and Giuseppe Zais. Zuccarelli, who spent considerable time in England, became renowned for his charming, decorative landscapes populated with elegant figures, often depicting picnics or gentle pastoral activities. His style was characterized by soft light, delicate colours, and a generally serene mood. Giuseppe Zais, influenced by Marco Ricci, also specialized in idyllic landscapes and rustic scenes, often featuring peasants and animals, rendered with a lively, somewhat looser brushstroke than Zuccarelli. Antonio Diziani's work clearly aligns with this pastoral tradition, absorbing influences from these prominent contemporaries.

Antonio Diziani's Artistic Style: Brushwork, Light, and Atmosphere

Antonio Diziani developed a distinctive and recognizable style within the pastoral landscape genre. His approach was characterized by a relatively quick, lively brushstroke, imbuing his scenes with a sense of immediacy and freshness. This technique, sometimes described as "pittura di tocco" (painting of touch), involved applying paint in visible dabs and strokes, allowing for texture and vibrancy, rather than striving for a perfectly smooth, blended finish. This approach was shared by other Venetian painters of the era, including his father Gaspare and contemporaries like Francesco Guardi, reflecting a broader Rococo aesthetic preference for spontaneity and decorative effect.

Colour and light play crucial roles in Diziani's landscapes. He typically employed a palette favouring soft, harmonious tones – gentle blues for the sky, varied greens and earthy browns for foliage and ground, often accented with touches of warmer colours in the figures' clothing or architectural elements. His handling of light is particularly adept, often using contrasts between illuminated areas and soft shadows to create a sense of depth and volume within the composition. He masterfully depicted the atmospheric effects of light, whether it be the warm glow of late afternoon sun or the gentle haze of a summer day, contributing significantly to the poetic mood of his works.

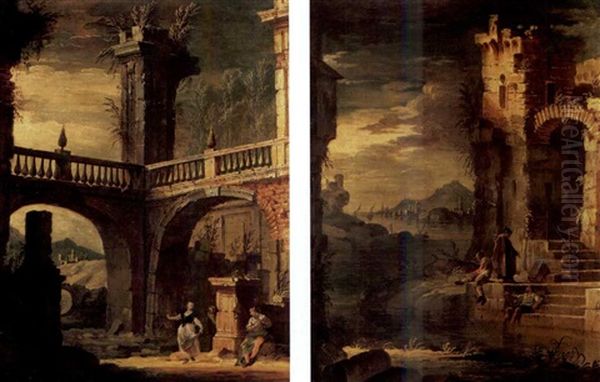

Compositionally, Diziani often favoured expansive views, drawing the viewer's eye into the scene through winding paths, rivers, or carefully placed groups of trees. He frequently structured his landscapes with a darker foreground framing a brighter middle ground and distant background, a conventional technique used effectively to enhance the illusion of deep space. Figures, typically shepherds, peasants, or travellers, are integrated naturally into the landscape, often depicted on a relatively small scale to emphasize the dominance of nature. While idealized, his landscapes often retain a sense of plausibility, rooted in observations of the Italian countryside, particularly evoking the rolling hills and rustic charm associated with regions like Tuscany, even though he worked primarily in Venice.

Key Themes and Representative Works

The predominant theme in Antonio Diziani's oeuvre is the pastoral idyll. His canvases are frequently populated with shepherds tending their flocks, peasant families resting or working, anglers by riversides, and travellers journeying through serene countryside settings. These scenes rarely depict specific events or narratives but rather aim to evoke a mood of tranquility, simplicity, and harmony between humanity and nature. This idealized vision of rural life resonated with the tastes of urban patrons who romanticized the perceived innocence and peace of the countryside, offering an escape from the complexities of city life.

While many of his works bear generic titles like "Pastoral Landscape," "Landscape with Figures and Animals," or "River Landscape," they consistently showcase his stylistic hallmarks. He often included elements like rustic buildings, classical ruins (a common motif in 18th-century landscapes, adding a touch of historical nostalgia), and picturesque bridges to enhance the visual interest and compositional structure of his scenes. The recurring motif of water, whether gentle rivers or calm lakes, allowed him to explore reflections and add another layer of luminosity to his work.

A particularly curious and noteworthy aspect of Antonio Diziani's output, though perhaps less common than his pastoral scenes, is his engagement with the genre of singerie. These are satirical or whimsical scenes depicting monkeys dressed in human clothes and engaging in human activities. In one known example attributed to him, "Monkey Masquerade" or similar titles, monkeys are shown mimicking various social roles – peasants, soldiers, aristocrats – in a playful, slightly absurd manner. This genre, popularized earlier by Flemish artists like David Teniers the Younger, was unusual in Italian art of the period and highlights a lighter, perhaps more humorous side to Diziani's artistic personality, likely intended for the amusement of specific patrons. These singerie stand out as intriguing anomalies within his largely pastoral body of work.

Influences and Artistic Connections

Antonio Diziani's artistic development was shaped by several key figures and the broader Venetian artistic milieu. The most immediate influence was undoubtedly his father, Gaspare Diziani. From Gaspare, Antonio likely inherited foundational techniques, a fluid handling of paint, and perhaps an inclination towards decorative compositions. However, Antonio consciously diverged from his father's focus on history and religious painting to specialize in landscape.

Within the landscape genre, the influence of Marco Ricci is palpable, particularly in the atmospheric quality and the compositional structures Diziani employed. Ricci was a foundational figure for 18th-century Venetian landscape, and his work provided a model for many subsequent artists, including Diziani. The impact of Francesco Zuccarelli and Giuseppe Zais is perhaps even more direct and evident in Antonio's style. The charm, delicate colour harmonies, and idyllic subject matter favoured by Zuccarelli find clear echoes in Diziani's work. Similarly, the lively brushwork and focus on rustic figures seen in Zais's paintings resonate with Diziani's approach. It is likely that Diziani looked closely at the successful formulas of these contemporaries, adapting elements to suit his own temperament.

While direct collaboration records between Antonio Diziani and figures like Zais or Marco Ricci have not been firmly established, the stylistic affinities strongly suggest a shared artistic environment where ideas and approaches circulated freely. Diziani operated within a rich network of Venetian artists. Though specializing in landscape, he would have been aware of the work of masters in other genres, such as the celebrated Giambattista Tiepolo, known for his vast, luminous frescoes, or Pietro Longhi, the chronicler of Venetian daily life in his intimate genre scenes. The delicate pastel portraits of Rosalba Carriera or the decorative schemes of Jacopo Amigoni also formed part of the artistic tapestry of the time, contributing to the overall Rococo sensibility that permeated Venetian art and influenced Diziani's aesthetic.

The Singerie Phenomenon Revisited

The creation of singerie, or monkey scenes, by Antonio Diziani warrants further consideration as it represents a fascinating, albeit minor, current in his work and in 18th-century taste. The depiction of monkeys aping human behaviour has roots in medieval marginalia but gained popularity as an independent genre particularly in Flemish painting of the 17th century, with David Teniers the Younger being a key exponent. These scenes often carried satirical undertones, using the monkeys to gently mock human follies, social hierarchies, or professions.

By the 18th century, the singerie had also found favour in France, aligning with the Rococo taste for the exotic, the whimsical, and the decorative. Artists like Christophe Huet decorated entire rooms with such scenes. Antonio Diziani's engagement with this theme places him within this broader European trend. His monkey masquerades, depicting monkeys dressed as aristocrats, soldiers, or peasants, likely functioned as light-hearted social commentary or simply as amusing, decorative pieces designed to entertain patrons.

The choice of this unusual subject matter highlights Diziani's versatility and his willingness to engage with less conventional artistic forms popular at the time. While his reputation rests firmly on his pastoral landscapes, the existence of these singerie adds an element of playful curiosity to his artistic profile. They demonstrate an awareness of international artistic trends and cater to a specific niche market within the broader demand for decorative paintings in Rococo Venice.

Later Career and Legacy

Antonio Diziani remained active as a painter in Venice throughout the latter half of the 18th century, continuing to produce the landscapes that had become his specialty. He appears to have enjoyed a steady career, finding patronage among those who appreciated his charming and skillfully executed pastoral scenes. His work maintained a consistent quality, adhering to the Rococo aesthetic even as Neoclassicism began to gain ground elsewhere in Europe towards the end of his life.

His position in Venetian art history is significant, particularly within the landscape genre. He is often regarded as one of the last notable exponents of the 18th-century Venetian tradition of pastoral landscape painting, carrying forward the stylistic currents established by Marco Ricci, Zuccarelli, and Zais. While perhaps not possessing the groundbreaking originality of a Canaletto or the dramatic flair of a Guardi, Diziani excelled in creating consistently pleasing, atmospheric, and technically proficient works that perfectly captured the idyllic spirit favoured by his patrons.

The influence of Antonio Diziani on subsequent generations of painters may have been less pronounced than that of some of his more famous contemporaries. However, his dedication to the landscape genre and his skillful synthesis of prevailing stylistic trends contributed to the enduring appeal of Venetian painting. His works continue to be appreciated today for their charm, decorative quality, and evocative portrayal of an idealized nature, offering valuable insight into the artistic tastes and sensibilities of 18th-century Venice. His paintings are held in various museums and private collections, serving as testament to his contribution to the final flowering of the Venetian school.

Historical Assessment and Conclusion

Antonio Diziani occupies a respected place in the annals of 18th-century Italian art. As an inheritor of the rich Venetian painting tradition, channeled through his father Gaspare and refined through his engagement with contemporaries like Zuccarelli and Zais, he became a master of the pastoral landscape. His work embodies the elegance, charm, and decorative sensibility of the Rococo era, offering idyllic visions of rural life that appealed strongly to the tastes of his time.

His technical skill is evident in his lively brushwork, his harmonious use of colour, and his adept handling of light and atmosphere, which combine to create scenes imbued with a gentle, poetic quality. While primarily focused on idealized landscapes, his occasional foray into the whimsical genre of singerie reveals a broader artistic range and an engagement with contemporary European trends.

Historically, Antonio Diziani represents the continuation and culmination of a specific strand of Venetian landscape painting. Working in the shadow of giants like Canaletto and Tiepolo, he nonetheless carved out a successful career and made a significant contribution to the genre. He is rightly remembered as a talented and characteristic painter of the Settecento Venetian school, whose works capture the enduring allure of the pastoral ideal and the final, luminous chapter of Venice's artistic supremacy. His paintings remain a delightful window onto the aesthetic preferences of his era, securing his legacy as a skilled interpreter of nature's gentle beauty.