Jacopo Robusti, known to the world as Tintoretto, stands as one of the towering figures of the Venetian School during the late Italian Renaissance. Born in Venice, likely in late 1518 or 1519, he lived and worked almost exclusively in his native city until his death on May 31, 1594. His adopted name, Tintoretto, meaning "little dyer," was a diminutive derived from his father's profession as a dyer (tintore). This nickname, however, belied the immense scale and ambition of his artistic vision, which would leave an indelible mark on the trajectory of European painting, bridging the gap between the High Renaissance and the emerging Baroque era.

Tintoretto's art is characterized by its dramatic intensity, achieved through bold compositions, energetic brushwork, and a masterful manipulation of light and shadow. He possessed an astonishing speed of execution, earning him another nickname, "Il Furioso" (The Furious), which reflected both the velocity of his painting process and the passionate energy embedded within his canvases. Alongside Titian and Veronese, Tintoretto forms the great triumvirate of painters who defined the Venetian Cinquecento, each contributing a unique voice to the city's vibrant artistic landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jacopo Robusti was born into the bustling world of Renaissance Venice, the eldest of perhaps more than twenty children. His father, Giovanni Battista Robusti, was a dyer, a common and essential trade in the city renowned for its textiles. From an early age, Jacopo displayed a natural inclination towards drawing, reportedly using his father's dyes to sketch on the workshop walls. Recognizing his son's talent, Giovanni arranged for him to enter the studio of the most celebrated Venetian painter of the time: Titian (Tiziano Vecellio).

This prestigious apprenticeship, however, was remarkably short-lived. According to early biographers Carlo Ridolfi and Marco Boschini, Tintoretto lasted only about ten days in Titian's workshop. The reasons remain debated: some accounts suggest Titian, already an established master, recognized the prodigious, perhaps threatening, talent in the young man and dismissed him out of jealousy. Others propose a clash of personalities or Tintoretto's independent spirit chafing under formal instruction. Whatever the cause, Tintoretto left Titian's studio, embarking on a path largely defined by self-teaching.

Undeterred, Tintoretto pursued his artistic education independently with fierce determination. He dedicated himself to studying the works of the masters he admired most. His famous motto, inscribed on his studio wall, declared his ambition: "Il disegno di Michelangelo e il colorito di Tiziano" (The drawing of Michelangelo and the color of Titian). He diligently studied casts of Michelangelo's sculptures and likely anatomical texts or even dissected corpses, as was common practice for artists seeking mastery of the human form, aiming to emulate the Florentine master's powerful figure drawing and dynamic sense of movement. Simultaneously, he absorbed the lessons of Venetian colorito, particularly the rich palettes and atmospheric effects pioneered by Titian and other local artists like Palma Vecchio. He may also have spent time observing the work of other Venetian painters, possibly including Bonifacio Veronese (Bonifacio de' Pitati), whose workshop was active during Tintoretto's formative years.

The 'Furious' Style: Drama, Light, and Speed

Tintoretto forged a style that was uniquely his own, distinct from the polished surfaces of Titian or the festive grandeur of Veronese. His approach was characterized by dramatic urgency and profound emotional depth. Central to his technique was his revolutionary use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro). He employed dramatic contrasts, often illuminating figures with flashes of intense light against deep, atmospheric darkness, heightening the scene's emotional impact and focusing the viewer's attention. This technique prefigured the tenebrism that would become a hallmark of the Baroque period, particularly in the work of Caravaggio.

His compositions were equally innovative and dynamic. Tintoretto frequently utilized daring perspectives, steep diagonals, and radical foreshortening to create a sense of swirling movement and spatial complexity. Figures rarely stand static; they twist, turn, gesture, and interact with an energy that seems barely contained by the canvas. He often arranged scenes as if viewed from an unusual angle, plunging the viewer directly into the heart of the action. To aid in visualizing these complex arrangements and lighting effects, he was known to create small wax or clay figures, arranging them in miniature stage-like boxes lit by candles to study the interplay of light and form before committing them to paint.

His brushwork, the source of the "Il Furioso" nickname, was rapid, energetic, and expressive. Unlike the meticulous layering (velature) favored by Titian, Tintoretto often applied paint quickly and directly, leaving visible brushstrokes that conveyed a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. This "prestezza" (speed) allowed him to work on the vast canvases required for Venetian churches and confraternities (Scuole) with remarkable efficiency, but it also sometimes drew criticism from contemporaries who favored a more refined finish. For Tintoretto, however, the expressive power and dramatic effect took precedence over polished detail. His aim was not simply to depict a scene but to immerse the viewer in its spiritual or emotional core.

Masterworks of Faith and Myth

Tintoretto's prolific career yielded an astonishing number of large-scale narrative paintings, primarily focused on religious subjects, but also encompassing mythology and portraiture. His works adorn numerous churches, Scuole (confraternity halls), and the Doge's Palace in Venice, making the city itself a living museum of his art.

An early breakthrough came in 1548 with The Miracle of the Slave (also known as Saint Mark Freeing the Slave), painted for the Scuola Grande di San Marco. This electrifying work, now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, depicts Saint Mark descending dramatically from the heavens to save a slave condemned for venerating the saint's relics. Its bold foreshortening, dynamic composition, and vibrant color announced the arrival of a major new talent, though its unconventional energy also provoked controversy.

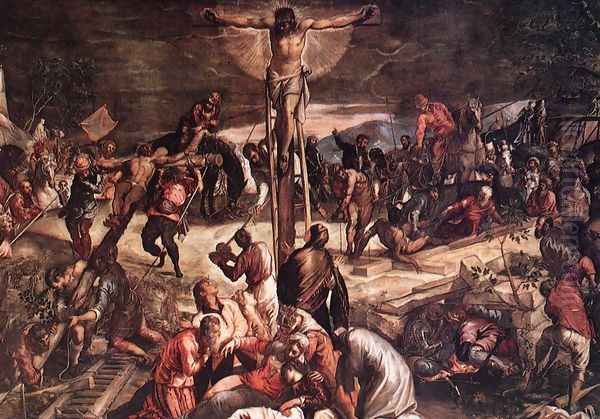

Tintoretto's most extensive and arguably greatest achievement is the vast cycle of paintings executed over more than two decades (c. 1564–1587) for the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. This commission provided him with an unparalleled opportunity to decorate the Sala dell'Albergo, the Sala Superiore (Upper Hall), and the Sala Terrena (Ground Floor Hall) with dozens of canvases depicting scenes from the Old and New Testaments. Working often for little more than the cost of materials, Tintoretto poured his energy into this project. Masterpieces within the cycle include the immense and deeply moving Crucifixion (Sala dell'Albergo), a panoramic vision of the event filled with raw emotion and dramatic lighting, and complex Old Testament scenes like The Brazen Serpent and Moses Striking the Rock in the Upper Hall ceiling, showcasing his mastery of complex multi-figure compositions viewed "di sotto in sù" (from below, looking up). The entire cycle stands as a testament to his narrative power and profound spiritual vision.

He also undertook major commissions for the Doge's Palace, the seat of Venetian government. Following fires in 1574 and 1577 that destroyed works by artists including Gentile da Fabriano, Pisanello, Gentile Bellini, Giovanni Bellini, Titian, and Veronese, Tintoretto played a key role in the redecoration. His most famous contribution is the colossal Paradise (Il Paradiso) on the end wall of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Hall of the Great Council). Measuring approximately 74 by 30 feet (22.6 by 9.1 meters), it is one of the largest oil paintings on canvas ever created. Completed with the help of his son Domenico in the late 1580s, it presents a swirling, celestial vision of Christ crowning the Virgin Mary amidst a multitude of saints and angels, a breathtaking display of compositional ambition and spiritual fervor.

Other significant works demonstrate the breadth of his genius. His various interpretations of The Last Supper are notable, particularly the version in the Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore (1592–1594). Unlike Leonardo da Vinci's balanced Renaissance composition, Tintoretto's interpretation is a whirlwind of supernatural light and shadow, with angels flitting through the rafters and the apostles arranged dynamically along a receding diagonal table, creating an intensely mystical and dramatic atmosphere. Susanna and the Elders (c. 1555–1556) showcases his skill in depicting the female nude within a complex spatial setting, while The Finding of the Body of Saint Mark (c. 1562–1566) uses dramatic perspective and ghostly light to create a scene of intense mystery and revelation. The Origin of the Milky Way (c. 1575) tackles a mythological theme with characteristic energy and luminous color.

Rivalry and Influence: Tintoretto in the Venetian Art World

Tintoretto operated within a highly competitive artistic environment in Venice. His primary contemporaries and rivals were the established Titian and the slightly younger Paolo Veronese. Titian, the undisputed master for much of the 16th century, represented the pinnacle of Venetian color and painterly technique. While Tintoretto deeply admired Titian's color, his own artistic temperament led him in a different direction, emphasizing drama and line alongside color. Their relationship, beginning with the aborted apprenticeship, seems to have remained somewhat distant, though Tintoretto undoubtedly respected the elder master's achievements.

Paolo Veronese offered a different kind of challenge. Veronese specialized in grand, luminous, and often festive scenes, characterized by opulent detail, clear light, and magnificent architectural settings, as seen in works like The Wedding at Cana. While both artists worked on vast scales and often competed for the same prestigious commissions (such as the redecoration of the Doge's Palace), their styles offered patrons a distinct choice. Veronese presented a vision of splendid, worldly ceremony, while Tintoretto offered intense spiritual drama and emotional depth. Their rivalry spurred both artists on, contributing to the richness and diversity of Venetian painting in the latter half of the century.

Beyond these giants, Tintoretto interacted with and influenced numerous other artists. His workshop included assistants and collaborators, most notably his own children. He would have been aware of the work of other Venetian painters like Jacopo Bassano, known for his rustic genre scenes and dramatic nocturnal settings, and Andrea Schiavone, whose style also showed Mannerist influences. Palma Giovane, a younger contemporary, worked alongside Tintoretto in the Doge's Palace and elsewhere, and his style shows Tintoretto's clear influence, alongside that of Titian (whose final Pietà Palma Giovane completed). Earlier figures like Paris Bordone, a pupil of Titian, also formed part of the artistic milieu Tintoretto navigated.

The Workshop and Enduring Legacy

Like most successful Renaissance artists, Tintoretto maintained an active workshop to help manage his numerous large-scale commissions. His most important collaborators were members of his own family. His daughter, Marietta Robusti (c. 1560–1590), became a skilled portrait painter in her own right, though her career was cut short by her early death. His son, Domenico Robusti (1560–1635), was his chief assistant, working closely with his father on many late projects, including the Paradise in the Doge's Palace, and continuing the workshop after Jacopo's death, largely imitating his father's style. Another son, Marco, also likely assisted in the workshop.

Tintoretto's working methods were geared towards efficiency. His legendary speed allowed him to undertake vast projects that might have daunted other artists. He was also known for being highly competitive in securing commissions, sometimes underbidding rivals or even offering to work for free or only for the cost of materials, as he did initially at the Scuola di San Rocco. This business acumen, combined with his immense talent and productivity, ensured a steady stream of work throughout his long career.

The legacy of Tintoretto's workshop extended beyond his immediate family. The Flemish painter Maerten de Vos (Martin de Vos) is sometimes mentioned as having spent time with Tintoretto during his visit to Italy around 1552, absorbing aspects of the Venetian master's dynamic style before returning to Antwerp. Tintoretto's approach to large-scale narrative painting and his dramatic use of light and composition became influential elements within the Venetian tradition carried forward by artists like Palma Giovane.

Echoes Through Art History

Tintoretto's impact extended far beyond Venice and his own lifetime. His dramatic intensity, emotional depth, and innovative techniques served as a crucial bridge between the High Renaissance and the Baroque. He is often considered a key figure in Mannerism, particularly in his elongated figures and complex poses, but his powerful use of light and shadow directly anticipates the Baroque aesthetic.

One of the most significant artists deeply influenced by Tintoretto was El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos). The Cretan-born artist spent time in Venice around 1567, where he undoubtedly absorbed the lessons of Tintoretto's dramatic compositions, flickering light, intense spirituality, and elongated figures before moving on to Rome and finally Spain. The stylistic affinities between the two artists are profound.

The revolutionary Baroque painter Caravaggio, working in Rome a few years after Tintoretto's death, likely knew his work through copies or examples that had traveled south. Caravaggio's dramatic use of tenebrism—plunging his scenes into deep shadow illuminated by harsh, focused light—owes a significant debt to the chiaroscuro pioneered by Tintoretto, although Caravaggio pushed it to even greater extremes.

Later Baroque masters also looked to Tintoretto. Peter Paul Rubens admired his energy, compositional dynamism, and painterly freedom during his own Italian sojourn. Even Rembrandt, the master of light and shadow in the Dutch Golden Age, shares an affinity with Tintoretto's dramatic illumination and psychological depth, though direct influence is harder to trace. Spanish masters like Velázquez, who visited Italy, certainly studied the Venetian masters, including Tintoretto, absorbing lessons in composition and brushwork.

Even centuries later, artists found inspiration in Tintoretto's passionate and dramatic style. The French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix admired his energy and expressive power. Art critics like John Ruskin in the 19th century championed Tintoretto, seeing in his work a profound moral and spiritual seriousness combined with supreme artistic skill. In contrast, figures associated with the classical tradition, like Nicolas Poussin, might be seen as reacting against the perceived excesses of Tintoretto's dramatic style, favoring order and clarity instead.

Final Years and Recognition

Tintoretto remained incredibly active into his old age. His late works, such as The Last Supper and The Gathering of Manna for San Giorgio Maggiore (1592–1594), show no diminution of his creative powers, displaying perhaps an even greater spiritual intensity and mastery of ethereal light effects. He continued to live and work in Venice, residing near the church of the Madonna dell'Orto in the Cannaregio district.

In the spring of 1594, Tintoretto complained of stomach pains and fever. He died on May 31, 1594, at the age of 75. He was buried in the church of Madonna dell'Orto, his parish church, where several of his own major paintings hang, including the monumental Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple and The Last Judgment. He was laid to rest in the family tomb where his beloved daughter Marietta had been buried four years earlier.

His death marked the end of an era in Venetian painting. While his son Domenico and Palma Giovane continued to work in a style heavily indebted to him, the sheer force and originality of Jacopo Tintoretto's vision were irreplaceable.

Tintoretto's Place in Art History

Jacopo Tintoretto remains one of the most powerful and original painters of the Italian Renaissance. His art embodies the energy, drama, and deep spirituality of Counter-Reformation Venice. By daringly combining Michelangelo's emphasis on form and dynamic movement with the Venetian tradition of rich color and atmospheric light, he created a unique and highly influential style.

His mastery of large-scale narrative, his innovative compositional techniques, his dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and the sheer emotional intensity of his work set him apart. While sometimes criticized in his own time and later for his rapid execution and lack of conventional finish, his "prestezza" was integral to the passionate immediacy of his art. He stands alongside Titian and Veronese as one of the three defining masters of 16th-century Venetian painting, contributing a voice characterized by profound drama and spiritual fervor. More than just a Venetian master, Tintoretto was a pivotal figure in the broader history of European art, a vital link between the Renaissance and the Baroque, whose furious brush left behind a legacy of breathtaking power and enduring influence.