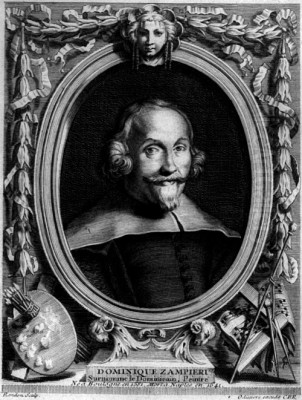

Domenico Zampieri, more famously known by the affectionate diminutive Domenichino, stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque art. Born in Bologna on October 21, 1581, and passing away in Naples on April 6, 1641, his career spanned a crucial period of artistic transition and development. As a central proponent of the Bolognese school and a leading light of Baroque classicism, Domenichino forged a path distinct from the dramatic intensity of Caravaggio and the high energy of some of his contemporaries, emphasizing clarity, emotional depth, and compositional harmony derived from classical and High Renaissance ideals, particularly those of Raphael. His meticulous approach and profound ability to convey human emotion earned him significant commissions and a lasting influence, despite facing considerable professional rivalry and criticism during his lifetime.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Domenico Zampieri's journey into the world of art began in the vibrant artistic milieu of late 16th-century Bologna. Born into modest circumstances – his father was a shoemaker – his innate talent for drawing became apparent early on. His initial formal training was under the guidance of Denis Calvaert, a Flemish painter who had established a successful studio in Bologna. Calvaert's workshop was a notable training ground, attracting other talented youths who would later achieve fame.

However, Domenichino's tenure with Calvaert was reportedly cut short due to a dispute. This led him to the most significant formative institution in Bologna at the time: the Accademia degli Incamminati (Academy of the Progressives), founded by the Carracci family – Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci. This academy was revolutionary, moving away from Mannerist artificiality towards a renewed study of nature, anatomy, and the masters of the High Renaissance.

Within the Carracci Academy, Domenichino found himself among a cohort of exceptionally talented peers, including Guido Reni and Francesco Albani. These artists, while developing individual styles, shared the academy's core principles of strong draughtsmanship (disegno), naturalism, and emotional clarity. Domenichino particularly gravitated towards Annibale Carracci, becoming one of his most dedicated pupils and later a trusted assistant. His small stature earned him the nickname "Domenichino" (Little Domenico) among his friends and mentors, a name that would stick throughout his career.

The Move to Rome and Collaboration with Annibale Carracci

Around 1602, following in the footsteps of his mentor Annibale Carracci and contemporaries like Reni and Albani, Domenichino moved to Rome. This relocation was pivotal, placing him at the epicenter of artistic patronage and innovation in Italy. Rome offered unparalleled opportunities to study classical antiquities and the masterpieces of Renaissance artists like Raphael and Michelangelo, which deeply resonated with Domenichino's artistic inclinations.

His initial years in Rome were closely tied to Annibale Carracci's workshop. He became an essential collaborator, most notably assisting Annibale on the monumental fresco cycle in the Farnese Gallery (Palazzo Farnese). This project, celebrating the loves of the gods, is considered a landmark of early Baroque art, blending Renaissance classicism with a new dynamism and sensuousness. Working alongside Annibale on such a prestigious commission provided Domenichino with invaluable experience in large-scale fresco painting and further solidified his adherence to the classical principles championed by his master.

This period also saw Domenichino absorbing the diverse artistic currents flowing through Rome. While firmly rooted in the Carracci tradition, he could not ignore the powerful, dramatic naturalism of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose works were causing a sensation. Though Domenichino's path diverged significantly from Caravaggio's intense tenebrism, the emphasis on realism and psychological depth found echoes, albeit translated into a more restrained and idealized idiom, in his own developing style.

Establishing Independence: Early Roman Commissions

As Domenichino gained experience and confidence, he began to secure independent commissions, allowing him to fully articulate his own artistic vision. Among his significant early works in Rome were the frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Saint Nilus the Younger at the Abbey of Grottaferrata, a project undertaken around 1608-1610. Here, working alongside Guido Reni initially, Domenichino demonstrated his growing mastery of narrative composition and his ability to infuse religious scenes with genuine human feeling.

Another important early commission was the decoration of the Oratory of Sant'Andrea adjacent to the church of San Gregorio Magno al Celio. Here, he painted the Flagellation of Saint Andrew, directly opposite a fresco of Saint Andrew Led to Martyrdom by his former fellow student, Guido Reni. This juxtaposition highlighted the subtle differences emerging between the two artists: Reni's graceful elegance versus Domenichino's more robust classicism and intense emotional focus.

These early projects showcased the hallmarks of Domenichino's style: meticulous preparation through numerous drawings, balanced and clearly structured compositions, figures possessing a sculptural solidity, and a profound attention to the affetti – the rendering of emotions and psychological states through expression and gesture. He became known for his ability to "reveal the soul," capturing subtle nuances of feeling that lent his religious and mythological narratives a compelling sincerity.

Masterpieces and Major Roman Projects

The second decade of the 17th century saw Domenichino rise to prominence, securing commissions for some of his most celebrated works. A defining achievement was the fresco cycle depicting the life of Saint Cecilia in the Polet Chapel of San Luigi dei Francesi (1613-1614). Works like Saint Cecilia Distributing Alms and the Martyrdom of Saint Cecilia exemplify his mature Roman style: complex multi-figure compositions managed with clarity, rich but harmonious color palettes, and figures whose gestures and expressions convey the narrative's emotional weight with dignity and pathos.

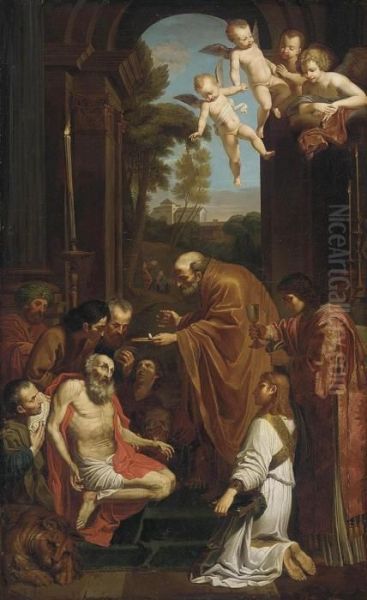

Perhaps his most famous single altarpiece from this period is The Last Communion of Saint Jerome, painted in 1614 for the church of San Girolamo della Carità (now housed in the Vatican Pinacoteca). This masterpiece, depicting the dying saint receiving his final communion, is renowned for its compositional brilliance, anatomical accuracy, and intense devotional feeling. It draws clear inspiration from an earlier painting of the same subject by Agostino Carracci, a fact that led Domenichino's rivals, particularly Giovanni Lanfranco, to accuse him of plagiarism.

This accusation of plagiarism became a significant controversy. While the compositional similarities are undeniable, Domenichino's interpretation possesses its own distinct power and emotional resonance. Later artists and critics, including Nicolas Poussin and Andrea Sacchi, staunchly defended Domenichino, arguing that emulation of admired masters was standard practice and that Domenichino had transformed, rather than merely copied, Agostino's model. Despite the controversy, the painting cemented Domenichino's reputation as a leading master in Rome. Another notable work, often associated with the Farnese family, is the enigmatic A Virgin with a Unicorn, showcasing his skill in handling mythological or allegorical subjects with grace.

The Pinnacle of Roman Success: Sant'Andrea della Valle

Domenichino's career reached a zenith with the commission to decorate the pendentives and apse choir of the vast new Theatine church of Sant'Andrea della Valle, one of the most prestigious projects available in Rome at the time. Beginning work in the 1620s, he painted the Four Evangelists in the pendentives supporting the dome, works lauded for their monumental grandeur and classical poise.

The commission for the apse choir, depicting scenes from the life of Saint Andrew, placed him in direct competition with his fierce rival, Giovanni Lanfranco, who was simultaneously painting the dome fresco of the Glory of Paradise. This juxtaposition starkly contrasted their artistic approaches: Domenichino's carefully composed, classically restrained narratives versus Lanfranco's dynamic, illusionistic High Baroque style, heavily influenced by Correggio. While Lanfranco's dome was perhaps more immediately dazzling, Domenichino's apse frescoes were praised for their narrative clarity and emotional depth.

During this period of high activity and recognition, Domenichino's status was further confirmed by the patronage of the Bolognese Pope Gregory XV (Ludovisi), who appointed him Papal Architect (though few architectural works materialized). He also served a term as principe (president) of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, the official artists' guild in Rome, signifying the high esteem in which he was held by his peers, despite ongoing rivalries.

Domenichino as a Landscape Painter

Beyond his celebrated work as a figure painter, Domenichino made significant contributions to the development of landscape painting. While often incorporating landscape settings into his narrative works, he also produced pure landscapes, which were highly influential. These were not typically topographical views but rather idealized landscapes, carefully constructed according to classical principles of order and harmony.

His landscapes often feature serene, expansive vistas with rolling hills, tranquil waters, classical buildings, and small figures drawn from mythology or biblical stories, such as in his Landscape with the Flight into Egypt. The compositions are balanced, the light is clear and even, and the mood is typically calm and contemplative. He structured his landscapes with clear foreground, middle ground, and background elements, often using trees or architecture as framing devices.

This structured, idealized approach to landscape profoundly influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly the French painters Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, who spent much of their careers in Rome. They adopted and further developed Domenichino's model of the classical landscape, which would become a dominant mode in European landscape painting for nearly two centuries. His 22 landscapes with views of the city, mentioned in sources, likely represented a major undertaking in this genre, emphasizing his commitment to it.

The Neapolitan Years: Triumph and Tribulation

In 1631, Domenichino accepted a lucrative and highly prestigious commission that took him away from Rome: the decoration of the Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro (Chapel of the Treasury of Saint Januarius) in Naples Cathedral. This was perhaps the most coveted commission in Naples, a city with a vibrant but fiercely competitive artistic scene. Domenichino was tasked with creating frescoes and altarpieces depicting scenes from the life of Naples' patron saint.

However, his time in Naples was fraught with difficulty and hostility. The local artistic community, dominated by painters like Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto), Belisario Corenzio, and Battistello Caracciolo, formed what became known as the "Cabal of Naples." This group allegedly resented the intrusion of an outsider, particularly one awarded such a prime commission, and reportedly engaged in intimidation, sabotage of his work, and threats against Domenichino and his assistants.

The pressure and persecution took a heavy toll on the artist. He felt isolated and endangered, even fleeing Naples for a period before being compelled to return to fulfill his contract. The work in the chapel proceeded slowly and under great duress. While he completed several oil paintings on copper for the altar niches and significant portions of the frescoes (including pendentives and lunettes), the project remained unfinished at the time of his death. His classical, restrained style also met with resistance in Naples, where the more dramatic, Caravaggesque tendencies exemplified by Ribera held greater sway.

Final Years and Death

The stress and antagonism Domenichino experienced in Naples undoubtedly contributed to his declining health. He died in Naples on April 6, 1641, at the age of 59. While illness was the likely cause of death, persistent rumors circulated, then and later, that he had been poisoned by his rivals in the Neapolitan Cabal. Though never proven, these rumors underscore the toxic atmosphere he endured during his final years.

His death left the decoration of the Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro incomplete. Giovanni Lanfranco, his old Roman rival, was briefly brought in, and eventually, Ribera himself contributed to the chapel's decoration, painting the altarpiece San Gennaro Emerging Unharmed from the Furnace. Domenichino's work in the chapel, though created under duress, still stands as a testament to his skill and dedication to his classical ideals even in an unreceptive environment.

Artistic Style and Technique Revisited

Domenichino's art is the epitome of Baroque Classicism, a style that sought to temper the dynamism and emotionalism of the Baroque with the order, balance, and idealized forms of the High Renaissance, particularly Raphael, and the principles learned from the Carracci. Central to his approach was disegno – the emphasis on drawing and design as the foundation of painting. He was a meticulous draughtsman, producing numerous preparatory studies for his compositions and figures.

His paintings are characterized by clarity of narrative and composition. Figures are typically arranged in a stable, often frieze-like manner, allowing for clear communication of the story and the emotional interactions between characters. He excelled in rendering the affetti, conveying a wide range of human emotions with subtlety and dignity, avoiding excessive melodrama. His use of color was rich and harmonious, often employing warm tones, and his handling of light and shadow aimed for clarity and modeling form rather than the dramatic contrasts of tenebrism associated with Caravaggio.

While sometimes criticized, particularly in the 19th century by figures like John Ruskin, for being overly academic or lacking spontaneity compared to artists like Lanfranco or Reni, Domenichino's deliberate and thoughtful approach resulted in works of profound psychological depth and enduring compositional strength. His dedication to classical ideals provided a significant counterpoint to other Baroque trends.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the challenges he faced, Domenichino's impact on the course of European art was substantial. In the 17th and 18th centuries, his reputation stood high, particularly among proponents of classicism. Theorists like Giovanni Pietro Bellori championed him as a model of ideal art, praising his adherence to classical principles and his mastery of expression.

His most significant influence was arguably on French artists working in Rome, most notably Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Poussin deeply admired Domenichino's narrative clarity, emotional gravity, and compositional rigor, which resonated with his own stoic classicism. Claude Lorrain built upon Domenichino's foundations in idealized landscape painting. Other Italian artists who absorbed aspects of his style include his pupils Andrea Sacchi, Giovanni Battista Passeri, and Francesco Cozza, as well as later classicizing painters like Carlo Maratta, Pier Francesco Mola, and Alessandro Turchi.

While his fame waned somewhat during the Romantic era and the 19th century, overshadowed by artists perceived as more passionate or revolutionary, the 20th and 21st centuries have seen a renewed appreciation for Domenichino's specific qualities: his technical mastery, his psychological acuity, and his crucial role in shaping the classical tradition within the Baroque period. His works remain key holdings in major museums worldwide, including the Louvre, the Prado, the National Gallery in London, the Uffizi, and the Vatican Museums.

Conclusion

Domenico Zampieri, or Domenichino, navigated the complex artistic world of 17th-century Italy to become a defining master of Baroque Classicism. From his training in the innovative Carracci Academy in Bologna to his major commissions in Rome and his troubled final years in Naples, he remained steadfastly committed to the principles of clear design, idealized form, and profound emotional expression. His masterpieces, such as The Last Communion of Saint Jerome and the frescoes in San Luigi dei Francesi and Sant'Andrea della Valle, showcase his ability to imbue religious and mythological narratives with both grandeur and intimate human feeling. As a highly influential landscape painter, he laid crucial groundwork for Poussin and Claude Lorrain. Though sometimes beset by rivalry and criticism, Domenichino's legacy endures as a cornerstone of the classical tradition in Baroque art, admired for his intellectual rigor, technical finesse, and the quiet intensity of his vision.