Charles Filiger stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure within the Symbolist movement and the vibrant artistic milieu of late 19th-century France. Born on November 28, 1863, in Thann, Alsace – a region then under German influence but culturally French – Filiger's artistic journey would lead him from academic training in Paris to the rustic, spiritually charged landscapes of Brittany, where he became associated with some of the most revolutionary artists of his time. His deeply personal, mystical, and often reclusive nature shaped an oeuvre characterized by its refined aesthetics, geometric precision, and profound spiritual introspection. Though his output was relatively small and his fame eclipsed by some of his contemporaries, Filiger's work offers a fascinating window into the diverse currents of Symbolism and the Pont-Aven School.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Charles Filiger's initial foray into the art world began with formal training. He enrolled at the Académie Colarossi in Paris, a progressive institution that served as an alternative to the more rigid, state-sponsored École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Colarossi was known for its diverse student body and its openness to modern artistic trends, providing a fertile ground for young artists seeking to break from academic convention. It was here that Filiger would have honed his foundational skills in drawing and painting. His early works, including watercolors, demonstrated a delicate touch and a keen eye for composition, leading to his exhibition of several such pieces at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1889. This early recognition hinted at a promising career, though Filiger would soon gravitate away from the mainstream Parisian art scene.

Brittany: The Call of Pont-Aven and Le Pouldu

The late 1880s marked a pivotal moment for Filiger. Drawn by the burgeoning reputation of Pont-Aven in Brittany as an artistic haven, he arrived in the region around 1888 or 1889. Brittany, with its rugged coastline, ancient traditions, and deeply ingrained Catholic faith, exerted a powerful pull on artists seeking authenticity and a spiritual alternative to the industrialized modernity of Paris. It was here that Paul Gauguin had begun to forge his revolutionary Synthetist style, attracting a circle of like-minded artists. Filiger quickly integrated into this group, settling first in Pont-Aven and later, alongside Gauguin and Meyer de Haan, at Marie Henry's inn, the Buvette de la Plage, in the more remote village of Le Pouldu.

This period was crucial for Filiger's artistic development. He formed close associations with key figures of the Pont-Aven School, most notably Paul Gauguin himself, but also Émile Bernard, whose theories on Cloisonnism (characterized by bold outlines and flat areas of color, akin to stained glass or cloisonné enamel) had significantly impacted Gauguin. Filiger also interacted with Paul Sérusier, who, after receiving Gauguin's famous "lesson" that resulted in The Talisman, became a pivotal figure in the formation of the Nabis group. Other artists in this vibrant Breton circle included Charles Laval, Gauguin's companion on his trip to Martinique, the Irish painter Roderic O'Conor, known for his expressive use of color, and Armand Séguin, a talented printmaker and painter.

The Development of a Unique Symbolist Vision

While Filiger absorbed the formal innovations of his Pont-Aven colleagues – the simplified forms, flattened perspectives, and emphasis on subjective experience – his artistic voice remained distinctly his own. His work became increasingly imbued with religious and mystical themes, reflecting his profound personal piety and introspective nature. He developed a meticulous, almost jewel-like technique, often working on a small scale with gouache and watercolor on paper or cardboard.

Filiger's style is characterized by a delicate linearity, a harmonious, often subdued color palette, and a tendency towards geometric stylization. He was deeply interested in early Italian Renaissance painting, particularly the works of artists like Giotto and Fra Angelico, whose spiritual intensity and clarity of form resonated with his own artistic aims. Furthermore, he drew inspiration from Byzantine art, with its hieratic figures, golden backgrounds, and emphasis on the transcendental. Breton folk art, including stained glass windows and religious sculptures, also informed his aesthetic, particularly in his depictions of local peasant piety. These diverse influences coalesced into a style that was both archaic and modern, decorative and deeply spiritual.

His figures, often Madonnas, saints, or praying Bretons, are rendered with a serene, almost impassive quality. Their faces are stylized, with elongated features and large, contemplative eyes. There is a sense of stillness and timelessness in his compositions, inviting quiet contemplation. Critic and writer Alfred Jarry, a contemporary and one of Filiger's earliest and most perceptive admirers, recognized the unique quality of his work, acquiring several pieces.

"Chromatic Notations": Towards Abstraction

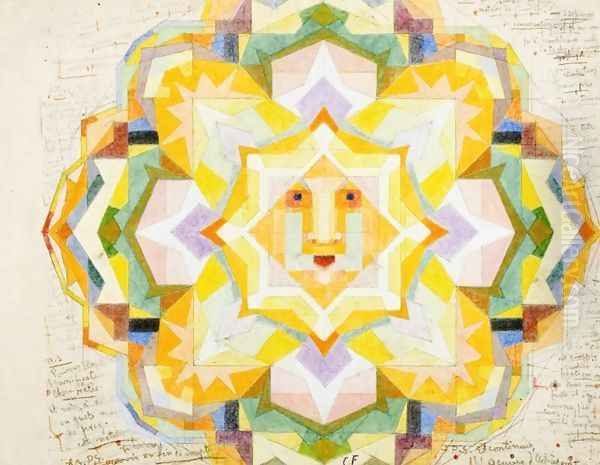

Later in his career, particularly after the turn of the century, Filiger's work evolved towards a more pronounced geometric abstraction. He began producing series of works he termed "Notations Chromatiques" (Chromatic Notations). These pieces, often small and meticulously executed, explored the interplay of geometric shapes, lines, and colors, arranged in intricate, almost musical patterns. While still retaining a sense of spiritual order, these works moved further away from direct representation, prefiguring some aspects of early 20th-century abstract art. Artists like Wassily Kandinsky, who was also exploring the spiritual dimensions of abstract form around this time, would later be seen as developing along similar, though distinct, paths. Filiger's "Chromatic Notations" represent a highly personal and innovative exploration of form and color, driven by an inner mystical vision.

Representative Works

Several works stand out in Filiger's oeuvre. Virgin and Child (c. 1892) is a quintessential example of his religious painting, showcasing the influence of Byzantine icons and Italian Primitives, with its stylized figures, serene expressions, and decorative patterning. The figures are outlined with a delicate precision, and the colors are applied in flat, harmonious planes. Another significant work, often titled The Golden Virgin or similar, further emphasizes the iconic quality of his religious imagery, often employing gold paint to enhance the spiritual, otherworldly atmosphere.

His depictions of Breton peasants, such as Breton Woman Praying, capture the profound and simple faith of the local people, a theme that resonated deeply with Filiger's own religious sensibilities. These works often feature figures in traditional Breton costume, their faces etched with devotion, set against simplified landscapes or interiors. His landscapes of the Breton coast, while less numerous, also possess a distinctive quality, often imbued with a mystical stillness and a subtle, abstracting simplification of natural forms. The "Chromatic Notations" series, as mentioned, represents a significant late development, showcasing his move towards a more purely abstract, spiritually infused visual language.

Exhibitions and Limited Recognition

Despite the originality of his art, Filiger's work was not widely exhibited during his lifetime. He participated in the Salon des Indépendants, a crucial venue for avant-garde artists, and notably, he exhibited at the Salons de la Rose+Croix. Organized by the eccentric Sâr Joséphin Péladan between 1892 and 1897, these Salons were dedicated to promoting Symbolist art with a strong mystical, esoteric, or religious bent. Filiger's art, with its spiritual themes and refined aesthetics, was well-suited to this venue, and he found a key patron in Count Antoine de La Rochefoucauld, a major supporter of the Rose+Croix Salons and a collector of Symbolist art. This patronage was vital for Filiger, who struggled financially throughout much of his life.

However, beyond these specialized circles, Filiger remained a relatively obscure figure. His reclusive nature, his preference for working on a small scale, and his increasing isolation contributed to his limited public profile. He was not a self-promoter in the way some of his contemporaries, like Gauguin, were.

Complex Relationships and Personal Struggles

Filiger's relationship with Paul Gauguin was one of mutual respect, though Filiger was undoubtedly influenced by the older artist's powerful personality and artistic innovations. However, as noted by some critics, Filiger did not fully absorb the more philosophical or "primitive" aspects of Gauguin's art. Instead, he adapted Synthetist principles to his own more delicate and introspective vision, focusing on the colorful patterns of Breton life and, more profoundly, on spiritual themes.

His interactions with Émile Bernard were also significant. Bernard's early experiments with Cloisonnism provided a formal language that Filiger found congenial. The Nabis artists, including Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard, shared some common ground with Filiger in their interest in spirituality, decorative qualities, and the subjective interpretation of reality, though Filiger remained more isolated from their group activities in Paris. Maurice Denis, in particular, with his famous dictum that a painting, before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order, articulated a principle that resonated with Filiger's own practice.

Filiger's personal life was marked by profound inner conflict. He was a devout Catholic, yet he grappled with his homosexuality, which caused him considerable guilt and anguish in the context of the societal and religious mores of the time. This internal struggle likely contributed to his reclusive tendencies and may have found an outlet in the intense spirituality and ascetic quality of his art. He lived a spartan life, often in poverty, and in his later years, he struggled with alcoholism and deteriorating mental health.

Later Years, Obscurity, and Posthumous Rediscovery

As the years passed, Filiger became increasingly isolated. He continued to live in Brittany, moving between various modest lodgings. He spent time in Le Pouldu, then Kersulé, near Plougastel-Daoulas, and eventually found refuge at the psychiatric hospital in Brest, where he continued to draw. His final years were spent in relative obscurity, and he died on January 11, 1928, in Plougastel-Daoulas.

For many years after his death, Charles Filiger was largely forgotten by the art world, overshadowed by the more prominent figures of the Pont-Aven School and the broader Symbolist movement. However, his work was not entirely lost to history. Alfred Jarry's early appreciation was a significant testament to his quality. A more substantial rediscovery began in the mid-20th century. The Surrealist leader André Breton, known for his interest in outsider art and artists with unique, visionary qualities, played a role in reviving interest in Filiger. Breton encountered Filiger's work and was struck by its mystical and almost hallucinatory precision, seeing in it a precursor to certain Surrealist sensibilities. He wrote about Filiger in his 1947 essay "L'Art magique," praising the "marvelous meticulousness" and "hieratic abstraction" of his art.

This renewed attention led to a gradual reassessment of Filiger's contribution. Exhibitions and scholarly research have since shed more light on his life and work, securing his place as a distinctive and important, if minor, master of the Symbolist era. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Fernand Khnopff, major figures of Symbolism, explored different facets of the movement, but Filiger's intensely personal fusion of religious mysticism, formal purity, and decorative abstraction remains unique.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Charles Filiger's legacy lies in the quiet intensity and spiritual depth of his art. He was not a prolific artist, nor did he seek the limelight, but his work possesses a rare integrity and a haunting beauty. He stands as a testament to the diversity of artistic expression within the Pont-Aven circle, demonstrating that Gauguin's influence could be assimilated and transformed in highly personal ways. His meticulous technique, his exploration of geometric form, and his profound engagement with spiritual themes distinguish him from his contemporaries.

His art speaks to a search for transcendence and inner peace, a quest that was perhaps all the more poignant given his personal struggles. In an era of rapid social and technological change, Filiger, like many Symbolists, sought refuge and meaning in the realm of the spirit, in the timeless traditions of faith, and in the enduring power of art to convey profound emotional and mystical experiences. Today, his delicate, jewel-like paintings and drawings continue to resonate with viewers who appreciate their refined aesthetics, their quiet intensity, and their glimpse into a deeply introspective artistic soul. He remains a fascinating figure, an artist whose singular vision offers a unique contribution to the rich tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century art.