Paul Sérusier stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from Impressionism to modern art in late 19th and early 20th century France. Born in Paris on November 9, 1864, and passing away in Morlaix, Brittany, on October 7, 1927, Sérusier was not only a painter of considerable influence but also a crucial theorist whose ideas helped shape the course of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. He is best remembered as a co-founder and intellectual guide of the Nabis group, acting as a vital conduit for the revolutionary ideas of Paul Gauguin and fostering a new direction in art that emphasized subjectivity, spirituality, and decorative form over realistic representation. His work and teachings laid significant groundwork for the abstract movements that would follow.

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Paul Sérusier was born into a prosperous Parisian family. His father, a successful businessman of Flemish descent working in the perfume industry, ensured his son received a first-rate education. Sérusier attended the prestigious Lycée Condorcet, a breeding ground for French intellectuals, where he excelled in classical studies. He immersed himself in philosophy, Greek, and Latin, alongside the sciences, demonstrating a keen intellect that would later characterize his theoretical approach to art. In 1883, he successfully obtained baccalauréats in both philosophy and science, equipping him with a broad intellectual framework that distinguished him from many artists of his generation. This rigorous academic background undoubtedly contributed to his analytical mind and his later propensity for formulating art theories.

Artistic Beginnings: The Académie Julian

Despite his academic achievements, Sérusier felt the pull of the visual arts. In 1885, rejecting a more conventional career path perhaps expected by his family, he enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris. This private art school was known for being less conservative than the official École des Beaux-Arts, attracting students seeking alternative approaches to art-making. It was here that Sérusier began his formal artistic training and, significantly, where he encountered fellow students who would become lifelong friends and collaborators. Among them was Maurice Denis, who would become another key figure and theorist within the Nabis movement. During these early years, Sérusier's work likely adhered to the prevailing academic or naturalistic styles, yet his time at the Académie Julian provided the connections and the environment that would soon lead him towards a radical artistic transformation.

The Turning Point: Pont-Aven and Gauguin

The summer of 1888 marked a decisive moment in Sérusier's artistic journey. Seeking inspiration away from the Parisian art scene, he traveled to Pont-Aven, a village in Brittany that had become an enclave for artists drawn to its picturesque landscapes and distinct local culture. It was here that Sérusier encountered the charismatic and revolutionary figure of Paul Gauguin. Gauguin, already breaking away from Impressionism towards a more synthetic and symbolic style, took the younger artist under his wing. This meeting proved transformative. Gauguin encouraged Sérusier to abandon the slavish imitation of nature and instead use color and form to express subjective feelings and ideas. He urged Sérusier to simplify, to exaggerate color, and to flatten perspective, principles central to the emerging style of Synthetism, also being explored concurrently by artists like Émile Bernard within the Pont-Aven school.

The Birth of an Icon: The Talisman

Under Gauguin's direct guidance, during a painting session in the Bois d'Amour (the Wood of Love) near Pont-Aven, Sérusier created a small, landscape painting on the lid of a cigar box. Gauguin famously instructed him: "How do you see these trees? They are yellow. So, put in yellow. How do you see this shadow? Rather blue. Render it with pure ultramarine. Those red leaves? Use vermilion." The resulting work, later christened Le Talisman (The Talisman), was a radical departure from naturalism. It featured bold patches of relatively pure, unmodulated color – vibrant yellows, blues, reds, and greens – arranged in simplified, almost abstract forms, representing the trees, path, and mill stream of the Bois d'Amour. The painting prioritized decorative arrangement and emotional resonance over literal depiction, embodying Gauguin's Synthetist principles. This small panel became a seminal work, not just for Sérusier, but as a foundational object for the Nabis movement.

Founding the Nabis

Returning to Paris in the autumn of 1888, Sérusier carried The Talisman like a relic, sharing it and Gauguin's revolutionary ideas with his fellow students at the Académie Julian. The painting's bold colors and simplified forms captivated a group of young artists eager to break from artistic conventions. This circle included Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Paul Ranson, among others. Inspired by Sérusier's experience and the painting itself, they formed a semi-secret brotherhood dedicated to exploring these new artistic avenues. Sérusier suggested the name "Les Nabis," derived from the Hebrew word for "prophets," signifying their mission to revitalize painting and imbue it with spiritual and symbolic meaning. Sérusier naturally assumed the role of the group's primary theorist, translating Gauguin's concepts and adding his own intellectual interpretations. The Nabis rejected the illusionism of academic art and the fleeting perceptions of Impressionism (as practiced by artists like Claude Monet), favoring instead subjective interpretation, decorative flatness, simplified forms, expressive color, and often drawing inspiration from Symbolist literature and spirituality. Other artists associated with the group included Ker-Xavier Roussel and later, the Swiss-born Félix Vallotton.

Sérusier's Artistic Development: Synthetism and Symbolism

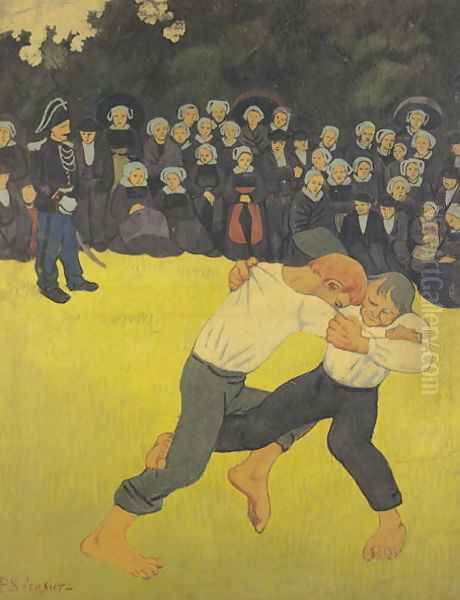

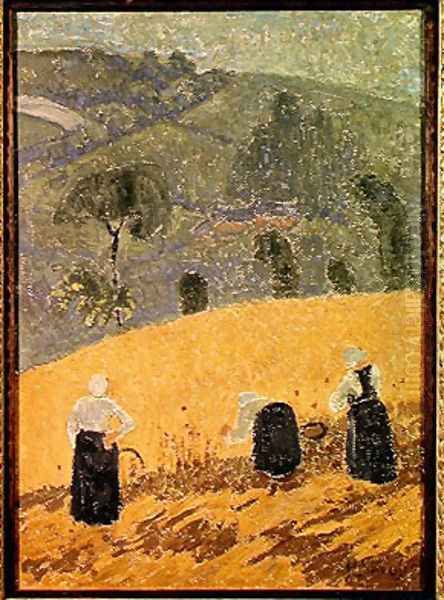

Following the pivotal experience of 1888, Sérusier's own painting style solidified around the principles of Synthetism. He continued to spend significant time in Brittany, particularly in Huelgoat and later Châteauneuf-du-Faou, finding inspiration in the region's landscapes and the perceived authenticity of its peasant life. His works from this period, such as Farmhouse at Le Pouldu (c. 1890) and Breton Eve (or Melancholy, c. 1890), showcase simplified, clearly delineated forms, often outlined in dark contours reminiscent of cloisonné enamel or stained glass (a technique also associated with Émile Bernard, termed Cloisonnism). Color was used non-naturalistically, chosen for its decorative and emotional impact rather than its descriptive accuracy. Works like The Fence (La Barrière, 1890) and Threshing Buckwheat (Le Battage du blé noir, 1890) exemplify this style, reducing complex scenes to essential shapes and resonant color harmonies. His interest in rural themes connected with a broader Symbolist fascination with 'primitive' cultures and a search for deeper, more universal truths beyond the surface appearances of modern life, a quest shared by Gauguin.

Deepening Spirituality: The Influence of Beuron

Sérusier's intellectual and spiritual inclinations led him to explore various esoteric and religious ideas. A significant influence came from the Benedictine Beuron Archabbey in Germany, which he visited in 1897, 1898 and later in 1903. There, he encountered the theories and art of Father Desiderius Lenz and the Beuron art school. Lenz advocated for an art based on sacred geometry, mathematical proportions, and Egyptian principles, believing these held the key to universal harmony and spiritual expression. This resonated deeply with Sérusier's own search for underlying order and meaning in art. The Beuron influence reinforced his move towards more structured, geometrically organized compositions and a heightened sense of symbolism in his work. While his painting never fully adopted the rigid formalism of the Beuron school, the experience deepened his commitment to art as a spiritual practice and informed his theoretical writings on harmony and proportion. This interest aligns him with other Symbolist artists like Odilon Redon, who also explored mystical and spiritual realms in their work.

Theoretical Contributions: ABC de la Peinture

While Sérusier continued to paint throughout his life, his role as a theorist became increasingly prominent. He was a thoughtful and articulate proponent of the Nabis' ideals, engaging in extensive correspondence, particularly with Maurice Denis, who was also a significant writer on art theory. Sérusier sought to codify the principles underlying their artistic practice. This culminated in his major theoretical work, ABC de la Peinture (ABC of Painting), published relatively late in his career, in 1921, although based on ideas developed over decades. The book summarized his theories on color relationships, form, composition, and the spiritual basis of art. He argued that painting should not aim to copy reality but to find visual "equivalents" for sensations and ideas, creating a harmonious arrangement that speaks directly to the viewer's emotions and intellect. The book remains an important document for understanding Nabis theory and Sérusier's contribution to modern art thought.

Teaching and Influence: The Académie Ranson

Sérusier's commitment to disseminating his artistic ideas extended to teaching. From 1908, he taught at the Académie Ranson, an art school founded in Paris by his fellow Nabi, Paul Ranson. While not the founder, Sérusier was a key instructor, teaching principles of color theory, composition, and the Nabis philosophy to a younger generation of artists. His teaching provided a platform to elaborate on the ideas he was developing for his ABC de la Peinture and ensured the continuation of the Nabis' influence beyond the group's most active period in the 1890s. His structured approach, informed by his intellectual background and his studies of principles like those found at Beuron, offered students a coherent alternative to both academic training and Impressionist spontaneity.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1912, Sérusier married Marguerite Gabriel-Claude, one of his former students at the Académie Ranson. However, their life together was marked by tragedy as Marguerite suffered from mental illness and required institutionalization. This personal hardship, coupled with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, led Sérusier to spend increasing amounts of time in Brittany, eventually settling permanently in Châteauneuf-du-Faou. While he continued to paint and completed his ABC de la Peinture, he became somewhat more isolated from the Parisian avant-garde. He passed away in Morlaix, Brittany, in 1927.

Despite his relative withdrawal in later years, Paul Sérusier's legacy is significant. He was a crucial catalyst for the Nabis movement, translating Gauguin's radicalism into a coherent set of principles for his contemporaries like Bonnard, Vuillard, and Denis. His painting The Talisman remains an iconic work of early modernism. As a theorist and teacher, he articulated a vision of art grounded in subjective expression, decorative harmony, and spiritual seeking, influencing subsequent developments. His emphasis on pure color and simplified form can be seen as anticipating aspects of Fauvism, championed by artists like Henri Matisse, and his theoretical explorations contributed to the climate that fostered early abstraction, as seen in the work and writings of Wassily Kandinsky on the spiritual in art. Today, Sérusier's works are held in major collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, recognized for their historical importance and their distinct contribution to the rich tapestry of modern art.

Conclusion

Paul Sérusier occupies a unique and vital space in the history of modern art. More than just a follower of Gauguin, he was an interpreter, a synthesizer, and a disseminator of new artistic ideas. Through his pivotal painting The Talisman, his role as the intellectual anchor of the Nabis, his thoughtful theoretical writings, and his teaching, he helped steer French art away from the naturalistic representation of the 19th century towards the more subjective, symbolic, and formally innovative paths of the 20th. He stands as a testament to the power of an artist who combined visual practice with intellectual rigor, leaving an indelible mark on the movements that would define modernism.