Émile Bernard stands as a fascinating and somewhat paradoxical figure in the narrative of modern art. A painter, printmaker, writer, poet, and theorist, Bernard was deeply involved in the Parisian avant-garde during a period of radical artistic transformation in the late 19th century. He was a close associate of giants like Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, playing a crucial, often debated, role in the development of key Post-Impressionist styles, notably Cloisonnism and Synthetism. Despite his early innovations and theoretical contributions, his later career took a different path, and his historical significance has sometimes been overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries. This exploration delves into the life, work, relationships, and enduring legacy of Émile Bernard, a pivotal yet complex artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Émile Henri Bernard was born in Lille, France, on April 28, 1868. His father was involved in the textile trade, a background that perhaps subtly influenced his later sensitivity to textures and patterns. His mother was supportive of his burgeoning artistic inclinations. The family dynamic was shaped early on by the illness of his younger sister, which led to young Émile spending considerable time with his maternal grandmother in Lille. His grandmother, who ran a successful laundry business employing numerous people, became a crucial source of emotional and financial support for his artistic ambitions throughout his life.

In 1878, the Bernard family relocated to Paris, exposing the young Émile to the vibrant cultural heart of France. He attended the Collège Sainte-Barbe before his artistic calling became undeniable. By the age of sixteen, he declared his intention to become a painter, a decision met with some disappointment by his parents but encouraged by his grandmother. In 1884, he fulfilled this ambition by entering the prestigious Atelier Cormon, a well-known academic studio in Paris.

At Fernand Cormon's studio, Bernard encountered other aspiring artists who would become significant figures, including Louis Anquetin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Here, he received formal training but also began experimenting with the newer styles captivating the Parisian scene, particularly Impressionism and the burgeoning Neo-Impressionism, or Pointillism, pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Bernard absorbed the theories of light and colour that underpinned these movements. However, his independent spirit and rapidly evolving, experimental tendencies soon clashed with the studio's more conservative expectations. In 1886, Cormon dismissed Bernard for displaying "insubordinate tendencies" – his work was already deemed too radically modern.

Forging Friendships and New Paths

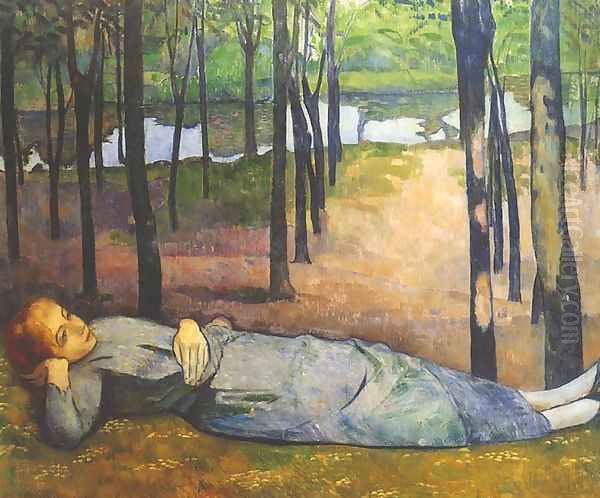

His expulsion from Cormon's studio proved to be a liberation rather than a setback. Freed from academic constraints, Bernard embarked on walking tours through Brittany and Normandy. These journeys were formative, exposing him to the rugged landscapes, distinct local cultures, and the strong traditions of folk art, which would profoundly influence his developing aesthetic. He sought an art form that moved beyond the purely optical concerns of Impressionism towards something more symbolic and emotionally resonant.

During this period, his network of artistic connections expanded. He maintained his friendship with Louis Anquetin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Crucially, it was also around this time, likely in late 1886 or early 1887, that he first encountered Vincent van Gogh in Paris. Van Gogh was then working at his brother Theo's gallery and frequenting the same artistic circles. They struck up a friendship, sharing an intensity and a desire to push the boundaries of painting. Bernard also met Paul Gauguin, initially perhaps through Van Gogh or other mutual acquaintances in Paris.

These relationships were vital. Bernard, Van Gogh, and Gauguin formed a trio bound by mutual respect, shared artistic goals, and intense intellectual exchange, primarily through letters and the exchange of works. They debated the future of art, critiqued each other's experiments, and dreamed of artistic collaborations. Van Gogh, in particular, envisioned forming an artists' collective in the South of France, a "Studio of the South," and invited both Bernard and Gauguin to join him in Arles – an invitation Gauguin would eventually accept, with tumultuous consequences.

The Pont-Aven School and the Genesis of Cloisonnism

Bernard's travels led him repeatedly to Brittany, particularly the village of Pont-Aven, which had become a popular destination for artists seeking picturesque scenery and a simpler way of life away from Paris. It was here, during the summer of 1886 and subsequent visits, that Bernard's artistic vision truly began to crystallize, partly in dialogue with Paul Gauguin, whom he met again and worked alongside there. Pont-Aven became the crucible for the development of new artistic ideas, fostering what became known as the Pont-Aven School, a loose group including artists like Claude-Émile Schuffenecker.

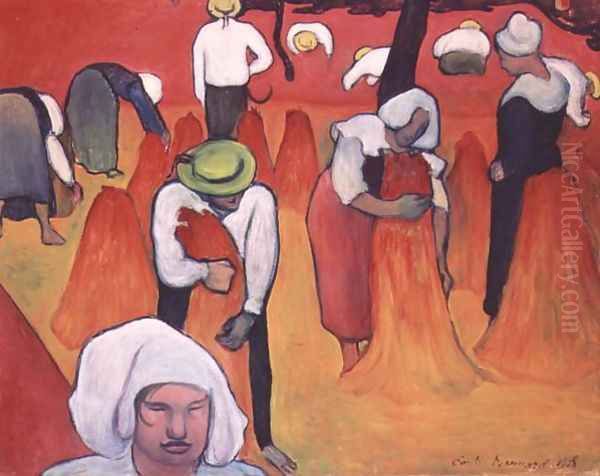

Working closely with Gauguin and influenced by his own experiments, as well as the bold, flat colours and strong outlines of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints (which were highly fashionable in Paris), Bernard developed a style known as Cloisonnism. The term, likely coined by the critic Édouard Dujardin, refers to the medieval technique of cloisonné enamelwork, where areas of coloured enamel are separated by metal wires. In painting, this translated to areas of flat, vibrant colour enclosed by thick, dark outlines. This style deliberately rejected the subtle light effects and broken brushwork of Impressionism in favour of simplification, flatness, and expressive colour.

Bernard's work from this period exemplifies the Cloisonnist approach. His painting Breton Women in the Meadow (also known as The Buckwheat Harvesters), dated 1888, is a seminal work of this style. It depicts Breton peasants in traditional dress arranged in a decorative, almost abstract pattern against a field. The forms are simplified, the perspective flattened, and the colours are bold and non-naturalistic, bounded by strong contours. The work emphasizes pattern and symbolic representation over realistic depiction. Another key work, Beggars of Clichy (1887), shows his early interest in depicting marginalized figures with a stark, graphic quality.

Synthetism: Collaboration and Controversy

Closely related to Cloisonnism, and often used interchangeably in discussions of the Pont-Aven group, is Synthetism. While Cloisonnism describes the visual technique, Synthetism refers more broadly to the underlying artistic philosophy. Developed concurrently by Bernard and Gauguin (with contributions from Anquetin acknowledged by Bernard), Synthetism aimed to synthesize three elements: the outward appearance of nature, the artist's feelings about the subject, and the aesthetic considerations of line, colour, and form.

Synthetism advocated for simplifying forms, using colour subjectively for emotional impact, and moving away from direct observation towards memory and imagination. The goal was not to copy reality but to create a visual equivalent – a synthesis – of the artist's inner experience and the external world. Bernard's Breton Women in the Meadow is considered a prime example of both Cloisonnism and Synthetism.

The question of who originated these ideas became a point of contention, particularly between Bernard and Gauguin. While Bernard was arguably the first to fully articulate and demonstrate the Cloisonnist technique in paintings like Breton Women, Gauguin quickly adopted and adapted these principles, becoming the more famous proponent of Synthetism. Bernard later felt that Gauguin had unfairly claimed credit for innovations they had developed collaboratively. This dispute would simmer for years, contributing to the eventual cooling of their relationship.

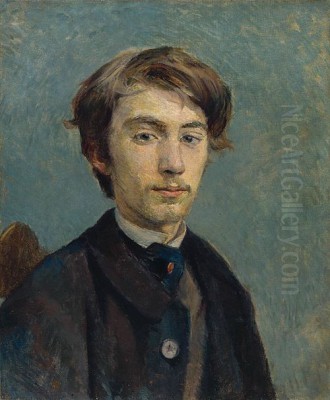

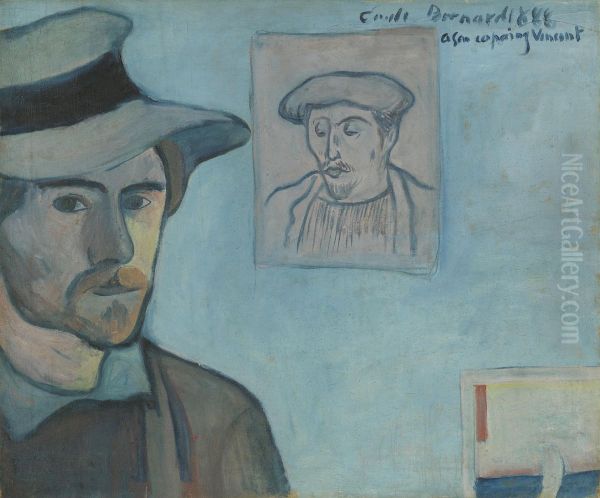

The Complex Triangle: Bernard, Van Gogh, and Gauguin

The interactions between Bernard, Van Gogh, and Gauguin between 1886 and 1890 are among the most documented and analyzed in art history, largely thanks to the extensive correspondence, especially Van Gogh's letters. Bernard played a significant role in this dynamic. He exchanged numerous letters and artworks with Van Gogh, sharing ideas about colour, composition, and the spiritual potential of art. In 1888, Van Gogh, then in Arles, suggested a portrait exchange between himself, Bernard, and Gauguin. Bernard painted a Self-Portrait with Portrait of Gauguin, and Gauguin painted a Self-Portrait with Portrait of Bernard, subtitling it Les Misérables. Van Gogh was deeply moved by these works, seeing them as symbols of their shared artistic quest.

Bernard's influence on Van Gogh during this period is evident. Van Gogh admired Bernard's bold simplifications and use of colour, even attempting works in a similar vein. However, Van Gogh also offered critiques, sometimes finding Bernard's work overly abstract or lacking in emotional depth compared to Gauguin's. The relationship was one of mutual influence but also critical distance.

When Gauguin joined Van Gogh in Arles in late 1888, Bernard remained in Pont-Aven or Paris, but he was intellectually present through letters. The intense, ultimately disastrous, collaboration between Van Gogh and Gauguin in the "Yellow House" was fueled by the Synthetist ideas Bernard had helped forge. After Van Gogh's breakdown and self-mutilation, and Gauguin's departure from Arles, the dynamics shifted. Following Van Gogh's death in 1890, Bernard played a crucial role in organizing memorial exhibitions and promoting Van Gogh's work, helping to establish his posthumous reputation. However, his relationship with Gauguin became increasingly strained, exacerbated by the dispute over the origins of Synthetism and Gauguin's growing fame.

Symbolism, Writing, and Theoretical Pursuits

Beyond his painting, Bernard was deeply immersed in the intellectual currents of the time, particularly the Symbolist movement in literature and art. He was an avid reader of Symbolist poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine and sought to imbue his art with symbolic meaning, moving beyond surface appearances to explore deeper emotions, ideas, and spiritual truths. His connections extended to Symbolist artists like Odilon Redon and sculptors like Auguste Rodin. He also had connections with the English artist Alphonse Legrand.

Bernard was a prolific writer throughout his life. He penned poetry, plays, art criticism, and theoretical essays. His writings provide invaluable insights into his own artistic intentions and the ideas circulating within the avant-garde. He published articles in Symbolist journals and later wrote extensively about the artists he knew, including Cézanne, Redon, Gauguin, and Van Gogh. His recollections, though sometimes coloured by personal biases and later resentments, are essential primary sources for art historians. His poetry collection, Le Cycle Humain, explored philosophical themes of human existence and life's transience.

His role as a theorist and critic grew, especially after Van Gogh's death. He championed the artists he admired and articulated the principles of the new art forms emerging from Post-Impressionism. He was an active participant in organizing exhibitions, including the influential shows at the Café Volpini in Paris in 1889, where he, Gauguin, and others from the Pont-Aven group exhibited works, explicitly positioning themselves against the official Salon and Impressionism.

Travels to Egypt and Italy: A Shift in Style

In 1893, facing personal difficulties and perhaps seeking to avoid military service, Bernard embarked on a journey that would significantly alter his life and art. He traveled to Italy and then Egypt, initially intending a short trip. However, he ended up staying in Egypt, primarily Cairo, for ten years. This extended period marked a distinct phase in his career. He immersed himself in the local culture, married a Lebanese woman named Hanenah Saati in 1894 (with whom he had several children, though tragically, three died young), and adopted aspects of the local lifestyle.

His art during the Egyptian decade shifted towards Orientalist themes, depicting street scenes, markets, and local figures. While some works retained elements of his earlier Synthetist style, many showed a gradual return towards more naturalistic representation and a greater interest in classical composition and technique. The vibrant, simplified forms of Pont-Aven gave way to more detailed observations, though often imbued with a sense of mystery or spiritual contemplation. This period distanced him from the rapidly evolving avant-garde scene in Paris.

After leaving Egypt in 1904, Bernard returned to Europe, spending time in Venice and Aix-en-Provence, where he visited Paul Cézanne shortly before the master's death. This encounter deeply affected Bernard. He published influential articles based on his conversations with Cézanne, contributing significantly to the understanding of Cézanne's complex artistic theories. However, Bernard's own artistic direction continued to move away from his radical youth. He became increasingly critical of modern art's trajectory, advocating a return to the principles of the Old Masters, particularly the Venetian painters like Titian and Veronese.

Later Life, Religious Art, and Legacy

In his later years, Bernard settled in Paris, where he continued to paint, write, and engage in art criticism. His painting style became markedly more traditional, often focusing on religious subjects, nudes, and allegorical scenes executed with a classical technique that bore little resemblance to the revolutionary work of his youth. He embraced Catholicism more deeply and briefly associated with the Rosicrucian movement, reflecting a lifelong spiritual quest that now manifested in more conventional forms.

He also dedicated himself to printmaking, producing woodcuts and lithographs, sometimes revisiting earlier Breton themes, as seen in his Les Bretonneries series. He held teaching positions, passing on his knowledge, though his teachings emphasized traditional methods over the avant-garde explorations he had once championed. He continued to write extensively, defending his own role in the development of modern art and sometimes expressing bitterness about being overlooked.

Émile Bernard died in Paris on April 16, 1941, during the German occupation. His legacy remains complex. For decades, his contributions were often minimized, seen primarily as a stepping stone for Gauguin or a correspondent of Van Gogh. His later turn towards traditionalism was viewed by many critics as a betrayal of his early promise. The disputes over the invention of Cloisonnism/Synthetism also clouded his reputation.

However, recent scholarship and exhibitions have prompted a significant re-evaluation of Bernard's role. Art historians now widely acknowledge his crucial part in formulating and disseminating the core ideas of Synthetism in the late 1880s. His early works, such as Breton Women in the Meadow, are recognized as groundbreaking masterpieces that directly influenced Gauguin and Van Gogh and pointed towards Fauvism and Expressionism. His writings remain invaluable historical documents. Works by Bernard are held in major museums worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, confirming his importance.

Conclusion: An Indispensable Innovator

Émile Bernard was more than just a witness to a pivotal moment in art history; he was an active participant and a catalyst for change. His early collaborations and theoretical insights were instrumental in shaping the course of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. Through Cloisonnism and Synthetism, he helped liberate colour and form from purely representational constraints, paving the way for many of the key developments of 20th-century art. His friendships and rivalries with Van Gogh and Gauguin highlight the intense, often fraught, personal dynamics that fueled artistic innovation. While his later career diverged from the avant-garde path he helped blaze, his youthful work retains its power and significance. Émile Bernard remains an indispensable figure for understanding the complex transition from Impressionism to Modernism, an artist whose innovative spirit and intellectual engagement left an indelible mark on the art world.