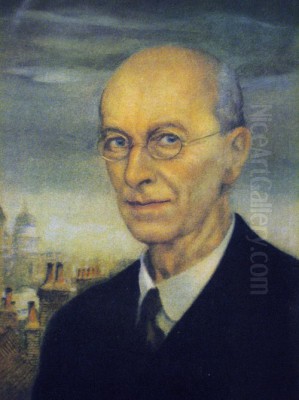

Arthur Rackham stands as one of the most influential and recognisable figures from the Golden Age of British Illustration, a period roughly spanning the late 19th century to the onset of the First World War. Born in London on September 19, 1867, and passing away on September 6, 1939, Rackham's career coincided with significant advancements in printing technology that allowed for the faithful reproduction of intricate colour illustrations. He masterfully utilised these developments, creating a body of work renowned for its fantastical subjects, distinctive style blending delicacy and grotesquerie, and profound connection to classic literature, fairy tales, and mythology. His illustrations did not merely accompany texts; they interpreted and enriched them, leaving an indelible mark on the visual imagination of generations.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Arthur Rackham was born into a reasonably large Victorian family in Lewisham, London, one of twelve children born to Alfred Thomas Rackham, a legal clerk at the Admiralty Marshal's office, and Annie Stevenson Rackham. From a young age, Arthur displayed a natural inclination towards drawing, a talent that was encouraged despite the practical expectations often placed upon children in that era. His health was somewhat delicate as a child, leading to a trip to Australia at the age of 17 in 1884 for recuperation, during which he continued to sketch.

Upon returning to London, Rackham initially pursued a conventional career path. He began working as a clerk at the Westminster Fire Office in 1885, a position he held for several years. However, his passion for art remained undiminished. Concurrently with his office job, he enrolled in evening classes at the Lambeth School of Art, studying under the landscape painter William Llewellyn. This period allowed him to hone his technical skills while still maintaining financial stability. The Lambeth School was known for its practical approach, fostering skills relevant to illustration and design, which undoubtedly benefited Rackham's future career.

The dual life of clerk and aspiring artist eventually reached a tipping point. By 1892, Rackham felt confident enough in his artistic prospects to resign from the security of his office job and commit himself fully to illustration. This was a bold move, reflecting his dedication and growing confidence in his abilities. He began contributing illustrations to various London periodicals, including The Westminster Budget, The Pall Mall Budget, and Scraps. This early journalistic work provided invaluable experience in working to deadlines and developing a narrative style, laying the groundwork for his transition into book illustration.

The Emergence of a Unique Style

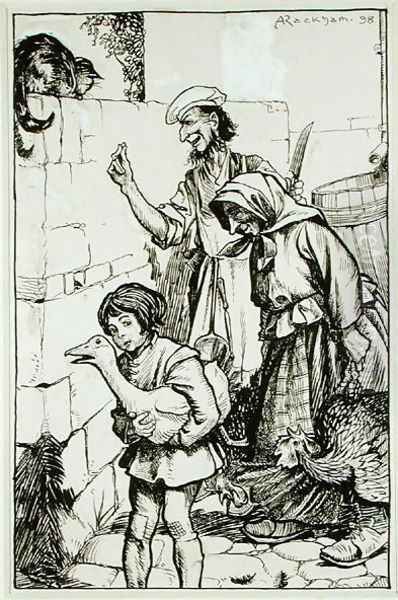

Rackham's early work showed promise, but it was in the realm of book illustration that his truly distinctive style began to flourish. An important early commission was for The Dolly Dialogues by Anthony Hope (1894), followed by illustrations for Washington Irving's The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1895) and Tales of a Traveller (1895). However, it was his work on The Ingoldsby Legends by Thomas Barham (1898, with a more complete edition in 1907) and Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1900) that began to showcase the unique blend of fantasy, detail, and character that would become his hallmark.

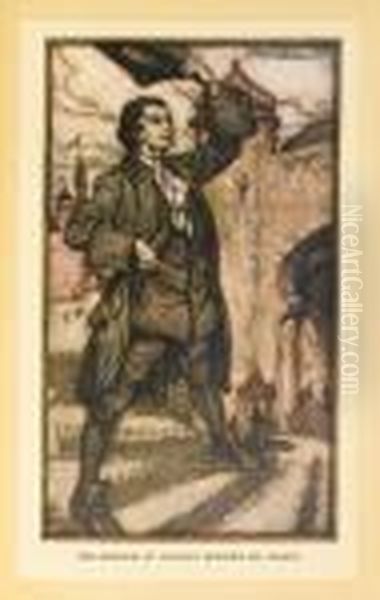

A pivotal moment arrived with the publication of Washington Irving's Rip Van Winkle in 1905. Published by William Heinemann, this book featured 51 colour plates by Rackham and was a resounding success. It firmly established his reputation as a leading illustrator. The timing was perfect; advancements in three-colour printing (halftone process) meant that the subtle nuances of his watercolour work could be reproduced with unprecedented fidelity for a mass market. This technological leap was crucial for Rackham, whose style relied heavily on delicate washes and intricate linework.

The success of Rip Van Winkle opened the floodgates for major commissions. Publishers recognised the commercial appeal of beautifully illustrated gift books, and Rackham was in high demand. His name became synonymous with high-quality, imaginative illustration, particularly within the genres of fantasy and children's literature.

Influences and Artistic Techniques

Arthur Rackham's style was not developed in isolation; it was a sophisticated synthesis of various influences, filtered through his unique sensibility. One can detect the sinuous, organic lines characteristic of the Art Nouveau movement, particularly the work of artists like Aubrey Beardsley, though Rackham's style was generally less decadent and more rooted in natural forms. The attention to detail and narrative clarity found in the work of earlier illustrators like George Cruikshank and the German artist Adolph Menzel also played a role.

Furthermore, Rackham drew inspiration from the Northern European artistic traditions, particularly the darker, more grotesque elements found in folklore and the work of artists like Albrecht Dürer. The gnarled trees, mischievous goblins, and wizened figures that populate his illustrations echo the rich mythology of the North. He was also significantly influenced by the aesthetics of Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), which became highly fashionable in Europe during the late 19th century. Artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige offered lessons in composition, the use of line, and flattened perspectives that Rackham absorbed into his own work, particularly visible in his treatment of landscapes and decorative elements.

Technically, Rackham was a master of pen and ink combined with watercolour. He typically began with a detailed pencil sketch, followed by precise and expressive ink lines that defined forms and textures. Over this linear framework, he applied layers of watercolour washes. He favoured a muted palette, often dominated by greens, browns, creams, and greys, which lent his work a distinctive, ethereal atmosphere. These subtle washes, built up layer by layer, created depth and luminosity. The combination of strong, descriptive linework and delicate colour was central to his appeal, allowing for both clarity and atmospheric suggestion. The halftone printing process was essential in capturing these subtleties for publication.

A World of Fantasy and Folklore

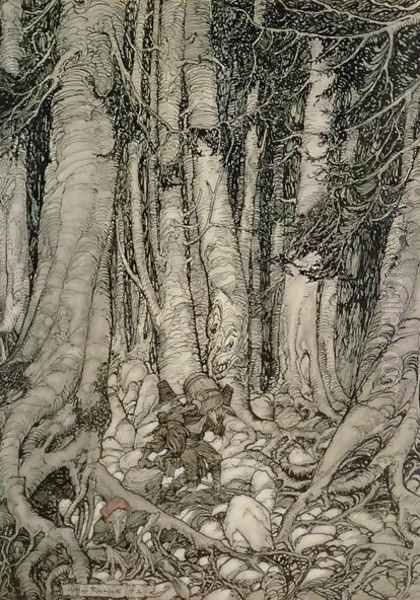

Rackham's name is inextricably linked with the world of fantasy, fairy tales, and mythology. He possessed an extraordinary ability to visualise the magical, the mythical, and the slightly menacing. His illustrations rarely depicted straightforward, brightly lit scenes; instead, they often dwelled in twilight realms, enchanted forests, and subterranean grottos. He excelled at portraying non-human creatures – fairies, elves, goblins, witches, trolls, and anthropomorphic animals and plants.

His trees are particularly noteworthy, often depicted as ancient, gnarled, and sentient beings, their branches twisting like arthritic fingers and their bark textured like wrinkled skin. These are not mere background elements but active participants in the narrative, embodying the mysterious and sometimes threatening power of nature. This personification extends to his depiction of wind, water, and earth, giving his landscapes a life of their own.

While capable of depicting beauty and grace, Rackham was equally adept at portraying the grotesque and the eerie. His witches are convincingly crone-like, his goblins suitably mischievous or malevolent, and his giants possess a palpable weight and awkwardness. Yet, even in his darker illustrations, there is often an undercurrent of humour or whimsy that prevents them from becoming truly terrifying, making them perfectly suited for children's literature that acknowledged the shadows as well as the light. This balance between the charming and the unsettling is a key characteristic of his work.

Landmark Illustrated Works

Following the success of Rip Van Winkle, Rackham embarked on a series of commissions that would become classics of illustrated literature.

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906): J.M. Barrie's text, originally part of his novel The Little White Bird, provided fertile ground for Rackham's imagination. His illustrations captured the magical realism of Peter Pan's early adventures among the fairies and birds of Kensington Gardens. The depictions of gossamer-winged fairies, the ethereal atmosphere of the gardens at twilight, and the sense of wonder and otherness cemented Rackham's reputation as the pre-eminent illustrator of fantasy. This work remains one of his most beloved and iconic contributions.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1907): Illustrating Lewis Carroll's masterpiece was a daunting task, given the iconic status of John Tenniel's original illustrations. Rackham, however, offered a distinctly different interpretation. His Wonderland is often darker, stranger, and more dreamlike than Tenniel's. His Alice is a more contemplative, less overtly Victorian child. The creatures she encounters, while sometimes humorous, often possess a slightly sinister or melancholic quality. Rackham's use of muted colours and intricate detail created a Wonderland that felt both familiar and unsettlingly new. While Tenniel's illustrations remain definitive for many, Rackham's version offered a compelling alternative vision that has earned its own devoted following.

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1908): Shakespeare's fairy play was a perfect match for Rackham's talents. His illustrations revelled in the magical atmosphere of the Athenian woods, populated by mischievous sprites like Puck and the regal figures of Oberon and Titania. He masterfully contrasted the ethereal fairy world with the comical "rude mechanicals," capturing the play's blend of enchantment and farce. The delicate rendering of fairy wings, moonlit landscapes, and expressive characterisations made this a standout work.

Grimm's Fairy Tales (1909, originally published 1900 with fewer illustrations): Rackham illustrated numerous tales from the Brothers Grimm, bringing classics like "Hansel and Gretel," "Snow White," and "Rumpelstiltskin" to life. His interpretations often emphasised the darker, folk-tale origins of these stories, depicting gnarled witches, deep forests, and moments of genuine peril alongside the expected magic and happy endings. His ability to convey character and emotion through posture and expression was particularly evident in these illustrations.

Undine (1909): Based on the romantic novella by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rackham's illustrations captured the watery, mythical nature of the titular water spirit and the tragic romance at the story's heart. His depictions of underwater scenes and ethereal figures were particularly effective.

Wagner's Ring Cycle (The Rhinegold & The Valkyrie, 1910; Siegfried & Twilight of the Gods, 1911): Tackling Richard Wagner's epic operatic cycle was an ambitious undertaking. Rackham rose to the challenge, creating powerful images of gods, heroes, giants, and dwarves drawn from Norse mythology. His illustrations conveyed the grandeur, drama, and mythical weight of Wagner's narrative, translating the operatic scale into visual terms. These remain some of his most dramatic and sought-after works.

Aesop's Fables (1912): Rackham brought his characteristic blend of detail and personality to the animal characters of Aesop's timeless moral tales, giving familiar figures like the Fox, the Crow, and the Tortoise vivid life.

A Christmas Carol (1915): Charles Dickens's festive classic received the Rackham treatment, resulting in memorable depictions of Ebenezer Scrooge, the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come, and the Cratchit family. Rackham captured both the ghostly chills and the heartwarming redemption of the story, adding his unique atmosphere to a much-loved text.

The Allies' Fairy Book (1916): Published during World War I with an introduction by Edmund Gosse, this collection featured tales from the Allied nations, illustrated by Rackham. It served as both entertainment and a piece of patriotic sentiment during a difficult time.

The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table (abridged from Malory by Alfred W. Pollard, 1917): Rackham tackled the foundational myths of Britain, illustrating tales of Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, and Merlin with a sense of medieval romance and magical enchantment.

Comus (by John Milton, 1921): Milton's masque provided scope for Rackham's depiction of both pastoral beauty and sinister enchantment, illustrating the tale of the virtuous Lady lost in a magical wood.

Peer Gynt (by Henrik Ibsen, 1936): In his later career, Rackham illustrated Ibsen's complex dramatic poem, capturing the fantastical and philosophical journey of its titular character, including memorable encounters with trolls in the Hall of the Mountain King.

The Wind in the Willows (by Kenneth Grahame, 1940): This was Rackham's final major project, published posthumously. Commissioned by the Limited Editions Club in the US, his illustrations for Grahame's beloved classic perfectly captured the charm, humour, and gentle Englishness of Mole, Ratty, Badger, and the irrepressible Mr. Toad. Despite being created while Rackham was suffering from the illness that would claim his life, the illustrations show no diminishment of skill or imagination, providing a fitting capstone to his career.

Other Notable Works and Contributions

Beyond these landmark publications, Rackham illustrated numerous other books, including editions of Feats on the Fjord by Harriet Martineau (1899), Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (various editions), Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens (1920), Where the Blue Begins by Christopher Morley (1922), Poor Cecco by Margery Williams Bianco (1925), The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving (1928), The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith (1929), The Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton (1931), Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (1933), and Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Mystery & Imagination (1935). His interpretation of Poe, in particular, allowed him to explore the macabre and psychologically intense aspects of his art.

He also provided illustrations for magazines and created advertising images, demonstrating his versatility. Furthermore, Rackham was an accomplished watercolour painter in his own right and exhibited his work regularly, including at the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours, of which he became a full member in 1908 (having been elected Associate in 1902). His work was exhibited internationally, earning him accolades such as a Gold Medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and a First Class Medal at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His work was even exhibited at the Louvre in Paris in 1914.

Personal Life and Professional Standing

In 1903, Arthur Rackham married Edyth Starkie (1867–1941), an accomplished painter and sculptor whom he had likely met while they were both students or exhibiting artists. They shared a creative life and had one daughter, Barbara, born in 1908. Edyth was a talented artist in her own right, exhibiting portraits and other works. The family lived for many years in the Chalcot Gardens area of Hampstead, North London, before moving to Limpsfield in Surrey in the 1920s. Rackham was known to be a quiet, hardworking, and somewhat reserved man, dedicated to his craft.

Professionally, Rackham achieved significant recognition and financial success. The popularity of his illustrated gift books, often issued in deluxe, signed limited editions alongside the standard trade editions, made him one of the most sought-after illustrators of his time. These limited editions, often bound in vellum and featuring high-quality paper and printing, are now highly prized by collectors. He worked closely with publishers like J.M. Dent and particularly William Heinemann, who published many of his most famous works. He was part of a vibrant artistic community that included fellow Golden Age illustrators like Edmund Dulac, Kay Nielsen, W. Heath Robinson, and Jessie M. King, each with their own distinctive style but sharing a commitment to imaginative and technically accomplished book illustration.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Arthur Rackham continued to work prolifically throughout the 1920s and 1930s, adapting his style subtly over time but remaining true to his core vision. Even as artistic tastes shifted towards Modernism, his work retained its popularity, offering an escape into worlds of magic and romance. He travelled, including trips to America, where he was highly regarded.

In his later years, Rackham developed cancer. Despite his illness, he continued to work with characteristic diligence, completing his final set of illustrations for Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows. He passed away at his home in Limpsfield, Surrey, on September 6, 1939, just as the world was descending into another global conflict.

Arthur Rackham's legacy is immense. He defined the visual language of fantasy for generations of readers and artists. His influence can be seen in the work of later fantasy illustrators, including figures like Alan Lee and Brian Froud, and even in the visual aesthetics of filmmakers such as Guillermo del Toro, who has cited Rackham as an inspiration. His ability to blend the beautiful with the bizarre, the delicate with the detailed, and the whimsical with the slightly unnerving created a unique artistic signature.

His interpretations of classic texts like Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, and A Midsummer Night's Dream remain iconic, existing alongside, and sometimes even overshadowing, other visual interpretations. The enduring appeal of his work lies in its technical brilliance, its imaginative depth, and its power to transport the viewer to realms just beyond the veil of the ordinary. Arthur Rackham was more than just an illustrator; he was a visual storyteller, a master craftsman, and a key architect of the modern fantasy aesthetic, securing his place as a giant of the Golden Age of Illustration. His works continue to be reprinted, collected, and cherished worldwide.

Conclusion

Arthur Rackham's contribution to the art of illustration extends far beyond the pages of the books he adorned. He elevated book illustration to a high art form, combining technical mastery with a unique and deeply personal vision. His world, populated by fairies, gnarled trees, mischievous goblins, and characters drawn from myth and legend, captured the imagination of the public during his lifetime and continues to enchant readers and inspire artists today. Through his distinctive blend of line and watercolour, his subtle palette, and his genius for characterisation and atmosphere, Rackham created an enduring legacy that confirms his status as a true master, whose work remains a benchmark of excellence in the Golden Age of Illustration and beyond.