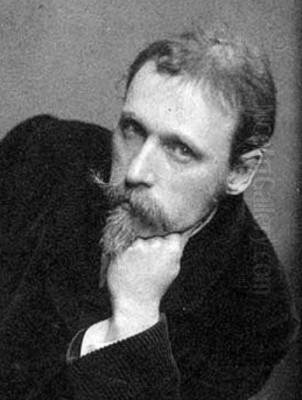

Walter Crane (1845-1915) stands as one of the most versatile and influential figures in British art and design during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. Born in Liverpool on August 15, 1845, Crane's life and career traversed the realms of painting, illustration, decorative design, art theory, education, and passionate socialist activism. His father, Thomas Crane, was a respected portrait painter and miniaturist, providing Walter with an early immersion in the world of art. Crane's multifaceted output left an indelible mark, particularly through his revolutionary contributions to children's book illustration and his central role in the burgeoning Arts and Crafts Movement. He passed away in Horsham, West Sussex, on March 14, 1915, leaving behind a rich legacy that continues to resonate.

Crane's formal artistic training began early. After his family moved to London, he demonstrated a precocious talent for drawing. At the young age of 13, in 1859, he was apprenticed to the prominent wood-engraver William James Linton. Linton was not only a master craftsman but also a Chartist and republican, and his workshop likely exposed the young Crane to both technical skills and radical political ideas. During his three-year apprenticeship, Crane learned the intricacies of drawing for wood engraving, a skill that would prove foundational for his later illustration work. He also had opportunities to study the work of contemporary artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, whose emphasis on detail and symbolism made an impression.

Furthering his education, Crane attended classes at Heatherley's School of Fine Art in London. His early artistic development was also significantly shaped by his study of Italian Renaissance masters, particularly the Florentine painters like Sandro Botticelli, whose linear grace he admired. A crucial influence, evident throughout his career, was Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), which were becoming increasingly available and fashionable in Europe. The bold outlines, flat areas of colour, and decorative compositions of artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige profoundly impacted Crane's approach to design and illustration, offering a compelling alternative to Western academic conventions.

The Illustrator: Revolutionizing Children's Books

Walter Crane's most widespread fame arguably stems from his work as an illustrator, particularly for children's books. His collaboration with the skilled colour printer and wood-engraver Edmund Evans, beginning around 1865, marked a turning point in the history of children's literature. Evans was pioneering new methods for colour printing from wood blocks, aiming for higher quality and more artistic results than the often crude colour printing previously available for cheap children's books. Crane's designs were perfectly suited to Evans's techniques.

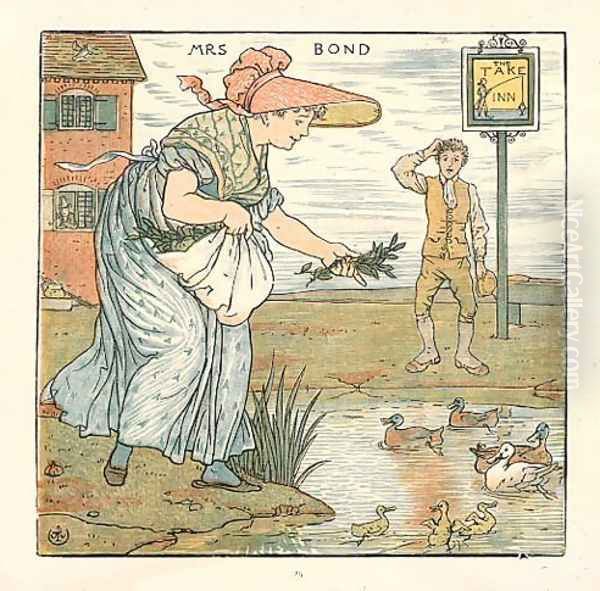

Together, they produced a series of innovative and immensely popular "Toy Books," published primarily by George Routledge & Sons. These shilling picture books, featuring traditional nursery rhymes and fairy tales like The Frog Prince, Sing a Song of Sixpence, and Beauty and the Beast, transformed the genre. Crane moved away from fussy Victorian naturalism towards a more decorative and stylized approach. His illustrations featured clear, bold outlines, flat planes of harmonious colour, and a strong sense of pattern and design. He often integrated text and image seamlessly within decorative borders, treating the entire page spread as a unified composition.

Crane's style in these books was a synthesis of influences: the linearity of Botticelli, the decorative flatness of Japanese prints, and an awareness of classical forms, all adapted into a visually engaging and child-friendly aesthetic. Titles like The Baby's Opera (1877), The Baby's Bouquet (1878), and The Baby's Own Aesop (1887) became nursery staples. These works, along with those of his contemporaries Kate Greenaway, known for her delicate depictions of childhood innocence, and Randolph Caldecott, celebrated for his lively sense of movement and humour, established a golden age of British children's book illustration. Crane, however, arguably brought a greater degree of sophisticated design and decorative richness to the form. His work elevated the picture book from a simple didactic tool to an object of art. He also collaborated with his brother, Thomas Crane, on works like At Home (1881).

The Designer: Embracing Arts and Crafts

Beyond illustration, Walter Crane was a pivotal figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, which emerged in Britain during the latter half of the 19th century. This movement was largely a reaction against the perceived decline in standards of design and craftsmanship brought about by industrial mass production. Its proponents advocated for the revival of traditional handicrafts, the unity of all arts (rejecting the hierarchy that placed fine art above decorative art), and the creation of beautiful, well-made objects for everyday life. They believed that good design could improve society and the lives of both makers and users.

Crane was deeply committed to these ideals. He was a close associate of William Morris, the movement's leading figure, sharing both his artistic principles and his socialist convictions. Crane contributed designs to Morris & Co. and was profoundly influenced by Morris's emphasis on pattern, nature-inspired motifs, and medieval craftsmanship. Crane became a tireless advocate for Arts and Crafts principles through his work, writings, and organizational activities.

He was a founding member of the Art Workers' Guild in 1884, an organization established to bring together architects, painters, designers, and craftspeople to foster collaboration and break down barriers between different artistic disciplines. Other founding members included architects and designers like W.R. Lethaby and Heywood Sumner. Perhaps most significantly, Crane was instrumental in founding the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1887 and served as its first president. This society organized regular exhibitions showcasing the best work in decorative arts and crafts, raising public awareness and setting standards for quality.

Crane's own design work spanned a remarkable range of media. He created influential designs for wallpapers, often featuring complex repeating patterns of flora and fauna, such as his well-known Peacock Garden design. He designed textiles, carpets, tapestries, stained glass, tiles (notably for Pilkington's Tile & Pottery Company), ceramics, and even complete interior decoration schemes. His designs often featured flowing lines, stylized natural forms, allegorical figures, and heraldic motifs, embodying the Arts and Crafts emphasis on beauty, utility, and skilled workmanship. He sought to bring art into every corner of the home, aligning with the movement's goal of integrating art into daily life, a philosophy shared by contemporaries like Philip Webb and C.R. Ashbee.

Painting and Fine Art

While renowned for illustration and design, Walter Crane also maintained a practice as a painter throughout his career, exhibiting regularly at venues like the Grosvenor Gallery and the New Gallery, which were known for showcasing more progressive art than the Royal Academy. His paintings often explored allegorical, mythological, and literary themes, reflecting his wide-ranging interests and his belief in art's capacity to convey ideas and ideals.

His style in painting often drew upon the influences visible in his other work. The linear elegance of Italian Renaissance artists, particularly Botticelli, remained a touchstone. This is evident in one of his most famous paintings, The Renaissance of Venus (1877), which clearly pays homage to Botticelli's Birth of Venus while reinterpreting the theme within Crane's own decorative idiom. The painting embodies the aesthetic ideals associated with the Aesthetic Movement, emphasizing beauty and artistic sensitivity.

Crane shared a close friendship and aesthetic affinity with the second-generation Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones. Both artists favoured elongated figures, dreamlike atmospheres, and themes drawn from myth and legend. Crane's paintings, like The Bridge of Life (1884) and Neptune's Horses (1892), showcase his skill in composition and his ability to create richly detailed, imaginative worlds. While perhaps less technically virtuosic in oil painting than contemporaries like Frederic Leighton or Albert Moore, Crane's paintings are significant for their consistent application of his decorative principles and their connection to the broader intellectual and artistic currents of his time, particularly the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements.

Art Nouveau Connections

Walter Crane's work, with its emphasis on flowing lines, stylized organic forms, and decorative integration, is often seen as an important precursor or parallel development to the international Art Nouveau style that flourished around the turn of the 20th century. While Crane himself sometimes expressed reservations about certain aspects of Art Nouveau, his own design vocabulary clearly shared many of its characteristics.

The sinuous curves found in his wallpaper and textile designs, the flattened perspectives and decorative borders in his illustrations, and his overall commitment to unifying art and life through design all resonate with Art Nouveau principles. His book designs, in particular, where cover, endpapers, title page, and illustrations were conceived as a harmonious whole, exemplify the Art Nouveau ideal of the 'total work of art' (Gesamtkunstwerk) applied to the book format.

While distinct from the sometimes more flamboyant or decadent expressions of Art Nouveau seen in the work of artists like Aubrey Beardsley in Britain, or continental figures such as René Lalique in France or Antoni Gaudí in Spain, Crane's style contributed significantly to the visual climate from which Art Nouveau emerged. His influence, particularly through his widely disseminated illustrations and designs, helped pave the way for the acceptance of a more linear, decorative, and non-naturalistic aesthetic across Europe and America. His work demonstrated how principles derived from Japanese art, Gothic forms, and Renaissance linearity could be synthesized into a modern decorative language.

Socialism and Political Art

Walter Crane was not merely an artist concerned with aesthetics; he was a deeply committed socialist who believed passionately in art's potential as a force for social change. His political awakening occurred in the early 1880s, and he became an active member of several socialist organizations, including the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) and later the Fabian Society and William Morris's Socialist League. He saw no contradiction between his artistic pursuits and his political activism; rather, he viewed them as interconnected aspects of a desire to create a more just and beautiful world.

Crane dedicated a significant portion of his artistic output to the socialist cause. He regularly contributed powerful cartoons and illustrations to socialist journals like Justice (the SDF newspaper) and Commonweal (the Socialist League's publication). These works often employed allegory and symbolism to critique capitalism, expose social injustice, and promote socialist ideals. One of his most famous political works is the cartoon The Triumph of Labour (1891), created for an International Workers' Day demonstration, depicting a hopeful procession of workers marching towards a future of socialism.

He designed banners for trade unions and socialist groups, membership cards, pamphlets, and posters, using his artistic skills to create a visual identity for the movement and communicate its message effectively. Crane believed that art should not be confined to galleries and the wealthy elite but should serve the people and contribute to the struggle for a better society. His commitment was unwavering; for instance, he publicly supported the Chicago Anarchists executed after the Haymarket Affair of 1886, an unpopular stance that reportedly damaged his prospects for commissions during a subsequent tour of the United States. Crane's work provides a compelling example of an artist integrating political conviction with artistic practice, influencing later traditions of political graphic art. His efforts aligned with the broader social conscience found in some Victorian art, though Crane's expression was far more explicitly political than, for example, the social commentary in the works of George Frederic Watts.

Educator and Theorist

Crane's commitment to the principles of art, design, and their social role extended into the field of education and theory. He held several important teaching positions, serving as Director of Design at the Manchester School of Art from 1893 to 1896, and briefly as Principal of the Royal College of Art in London from 1897 to 1898. Through these roles, he sought to reform art education, emphasizing the importance of practical design skills alongside drawing and painting, and promoting the Arts and Crafts ideal of the artist-craftsman.

He was also a prolific writer and lecturer on art and design. His books became standard texts and disseminated his ideas widely. Key publications include The Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New (1896), Line and Form (1900), and Of the Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New (1900). In these works, Crane articulated his theories on the principles of design, the history of illustration, the relationship between form and function, and the importance of decorative art. He stressed the fundamental role of line, the value of studying historical styles (while adapting them creatively), and the need for designers to understand the materials and techniques of their craft.

His writings consistently emphasized the social function of art and design and the importance of integrating aesthetic considerations into everyday life. He argued for a holistic approach to art education that equipped students not only with technical skills but also with a sense of historical context and social responsibility. His theoretical contributions, alongside his practical work, helped to shape design education and theory in Britain and beyond.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Walter Crane continued to be active as an artist, designer, and writer, travelling extensively, including trips to the United States, Italy, Greece, Germany, and Hungary, often lecturing and exhibiting his work. His international reputation was considerable. However, his personal life was marked by tragedy when his wife, Mary Frances Crane, whom he had married in 1871 and with whom he had several children, was killed in a train accident in December 1914. Crane was deeply affected by her sudden death and died himself only a few months later, on March 14, 1915, at the age of 69.

Walter Crane's legacy is multifaceted and enduring. He fundamentally changed the landscape of children's book illustration, setting new standards for artistic quality and design integration that influenced subsequent generations of illustrators, potentially including figures like Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, known for their own decorative styles. As a central figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, he championed the value of craftsmanship and the integration of art into daily life, leaving behind a significant body of work in decorative design that continues to be admired and studied.

His commitment to socialism and his pioneering use of art for political purposes mark him as an important figure in the history of graphic design and social commentary. Furthermore, his work as an educator and theorist helped to shape modern approaches to art and design education. Crane's unique synthesis of artistic talent, design innovation, and social conscience makes him a pivotal figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art history, whose influence extended across multiple fields and national borders. He remains celebrated for the sheer breadth of his creativity and his unwavering belief in the power of art to enrich and transform human life.