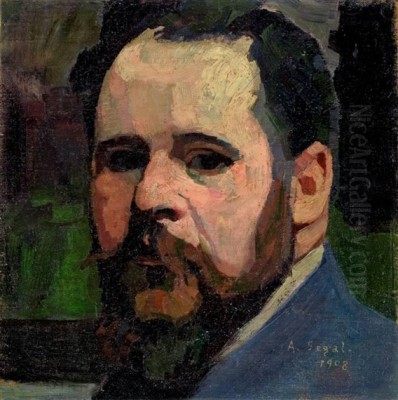

Arthur Segal stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European modernism. Born in Romania and later navigating the tumultuous artistic and political scenes of Germany, Switzerland, and England, Segal forged a unique path that intersected with major movements like German Expressionism and Dadaism. His life (1875-1944) spanned a period of intense artistic innovation and devastating conflict, both of which deeply marked his work. He was not only a painter and printmaker but also an influential teacher and theorist, developing a distinct artistic philosophy centered on the "Principle of Equivalence" and pioneering the use of art in therapeutic contexts. His journey reflects the broader experiences of many European artists, particularly those of Jewish heritage, grappling with modernity, war, and exile.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Arthur Segal was born into a Jewish family in Iași (Jassy), the historical capital of Moldavia, Romania, on July 23, 1875. His early artistic inclinations led him away from his homeland to the vibrant art centers of Europe. In 1892, seeking formal training, he enrolled at the Berlin Academy of Arts. There, he studied under established figures, notably the landscape painter Eugen Bracht, absorbing the academic traditions prevalent at the time.

His quest for artistic knowledge didn't stop in Berlin. Segal continued his studies in Munich, another crucial hub for artistic development in Germany. He attended a private painting school where he received instruction from Ludwig Schmidt-Reutte and Friedrich Fehr. Further broadening his horizons, he also spent time studying at the Munich Academy of Arts under Carl von Marr. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Segal also made the pilgrimage to Paris, immersing himself in the city's dynamic art scene, which was then the epicenter of avant-garde experimentation.

During these formative years, Segal's style initially aligned with the prevailing trends of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism. He explored the effects of light and color, techniques pioneered by French masters like Claude Monet and Georges Seurat. This early phase provided him with a solid foundation in painting techniques and color theory, which would remain important even as his style evolved dramatically in subsequent years. His experiences across these major European art capitals exposed him to a wide range of influences, setting the stage for his later engagement with more radical modernist movements.

Berlin and the Rise of Expressionism

In 1904, Arthur Segal chose Berlin as his base, settling in the rapidly modernizing German capital. This move placed him at the heart of burgeoning artistic developments, particularly the rise of German Expressionism. Berlin was a crucible of creative energy, attracting artists eager to break from academic constraints and forge new, emotionally charged forms of expression. Segal quickly became involved in the city's avant-garde circles.

He established connections with key figures and groups driving the Expressionist movement. Notably, he associated with artists from both Die Brücke (The Bridge), founded in Dresden in 1905 and later relocating to Berlin, which included figures like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Max Pechstein, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), centered in Munich around Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. While not formally a member of these core groups, Segal shared their interest in subjective experience, bold color, and simplified forms.

Segal's engagement with the Berlin avant-garde culminated in a significant organizational role. In 1910, frustrated by the conservative exhibition policies of the established Berlin Secession, Segal became a co-founder of the Neue Sezession (New Secession). This breakaway group provided a crucial platform for artists whose work was deemed too radical by the older institution. It brought together members of Die Brücke and other independent Expressionists, creating a powerful showcase for the new art. Segal's involvement underscored his commitment to promoting modernist principles and supporting fellow artists challenging the status quo. He exhibited his work actively, including shows promoted by the influential dealer and publisher Herwarth Walden in his Der Sturm gallery, a key venue for Expressionist and other avant-garde art from across Europe.

Wartime Exile and the Dada Connection

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 profoundly disrupted European society and the lives of its artists. As a Romanian citizen of Jewish descent and holding pacifist views, Segal found his position in wartime Germany increasingly untenable. Seeking refuge, he moved with his family to Ascona, Switzerland, a locality in the canton of Ticino known for attracting artists, intellectuals, and reformers seeking alternative lifestyles. Switzerland's neutrality offered a haven from the conflict engulfing the continent.

During his time in Switzerland, Segal became closely associated with the Dada movement, which erupted in Zurich in 1916, centered around the Cabaret Voltaire. Dada was an artistic and literary movement born out of disgust with the war and the nationalist, bourgeois values that had led to it. It embraced irrationality, chance, and anti-art gestures. Segal exhibited his work at the Cabaret Voltaire and contributed woodcuts to important Dada publications, including Dada 3 and Der Zeltweg. He interacted with key Dada figures such as Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp, and possibly encountered others like Marcel Duchamp and Paul Valéry who were part of the wider Dada network or spirit.

This period was artistically fertile for Segal. He continued to develop his distinctive style, often working in woodcut, a medium favored by many Expressionists and Dadaists for its directness and graphic power. It was during his Swiss exile, around 1918, that he created the sculpture Solomon's Wife Saba, indicating his exploration extended beyond two-dimensional work. His engagement with Dada, while perhaps less anarchic than some of its proponents, reinforced his commitment to questioning artistic conventions and exploring new theoretical grounds, leading towards his later formulation of the "Principle of Equivalence."

Return to Berlin and the Novembergruppe

Following the end of World War I, Arthur Segal returned to Berlin in 1920. The city, now the capital of the Weimar Republic, remained a vibrant, albeit politically unstable, center for artistic experimentation. Segal re-immersed himself in the avant-garde scene and became an active participant in its post-war manifestations. He joined the Novembergruppe (November Group), an association of radical artists and architects formed in the revolutionary atmosphere following the war's end.

The Novembergruppe aimed to bridge the gap between art and the people, advocating for the role of modern art in shaping a new society. Its membership was diverse, encompassing Expressionists, Cubists, Futurists, Dadaists, and abstract artists. Segal's studio in Charlottenburg became a meeting place for members of this group and other intellectuals, fostering lively discussions and exchanges. Figures like the critic Adolf Behne, and Dada artists Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch were part of this milieu, reflecting the interconnectedness of Berlin's avant-garde networks.

During the 1920s, Segal also established his own painting school, the Segal-Malschule, in Berlin. This marked the beginning of his significant career as an art educator, a role he would continue for the rest of his life. His teaching activities ran parallel to his artistic production. It was in this period that he fully developed his mature style, often characterized by a unique approach to composition and color, sometimes referred to as a form of prismatic Cubism. Works like Stilleben mit Flasche (Still Life with Bottle) from 1924, exhibited in Berlin the following year, and Heligoland from 1923, which explored optical phenomena through geometric forms and vibrant color, exemplify his artistic concerns during this productive decade.

The Principle of Equivalence and Prismatic Style

A defining aspect of Arthur Segal's contribution to modern art theory and practice was his development of the "Principle of Equivalence" (Prinzip der Gleichwertigkeit). Emerging fully in the years after his return from Switzerland, this concept informed his distinctive visual style. The principle advocated for the equal importance of all elements within a composition, rejecting traditional hierarchies that emphasized a central subject or focal point. Segal sought to create a democratic visual field where figure and ground, object and space, held equal value.

Visually, this principle often manifested in a structured, grid-like division of the canvas. Segal would partition the picture plane into multiple rectangular or geometric zones. Each segment contained part of the overall scene, rendered with careful attention to color and form, but integrated into a balanced, non-hierarchical whole. This approach created a faceted, prismatic effect, breaking down objects and spaces into interlocking planes of color and light. While sometimes compared to Cubism, Segal's method was less about deconstructing objects from multiple viewpoints and more about achieving an overall equilibrium and optical harmony across the entire surface.

Some interpretations suggest a connection between Segal's Principle of Equivalence and his Jewish background, particularly the egalitarian and anti-hierarchical tenets found in Hasidic thought, which originated in Eastern Europe. This philosophical underpinning aimed to imbue the artwork with a sense of unity and spiritual balance, approaching a "truth" or "spiritual form" through a decentralized, non-judgmental representation. His theoretical writings, including a paper on the problem of light in painting co-authored with Nikolaus Braun in 1925, further elaborated his ideas. This unique synthesis of theory and practice marks Segal as an original thinker within the modernist landscape.

Flight from Nazism and Later Years in London

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in Germany in 1933 marked a catastrophic turning point for modern artists, particularly those of Jewish descent or associated with avant-garde movements deemed "degenerate" by the regime. Arthur Segal, fitting both categories, faced immediate persecution. His art was condemned, and his ability to work and teach was severely curtailed. Like many others, he was forced to flee Germany to ensure his safety and continue his artistic practice.

Segal initially sought refuge on the Spanish island of Mallorca in 1933. The Mediterranean environment offered a temporary respite, but the looming Spanish Civil War soon made Spain unsafe as well. His journey as an émigré eventually led him to England. He settled in London in 1936, where he would spend the final years of his life. London became the last major center for his artistic and educational activities.

Life as a refugee in London presented new challenges, but Segal remained resilient and productive. He continued to paint and exhibit his work, finding a place within the community of exiled artists and intellectuals who had gathered in Britain. He also re-established his role as an educator, recognizing the profound need for creative expression and support among fellow refugees, especially the young. His final years were dedicated to both his own art and to fostering the talents and well-being of others displaced by tyranny.

Art as Therapy and Educational Legacy

In London, Arthur Segal founded his own art school, later known as the Arthur Segal School for Painting and Sculpture, located in Hampstead. This school became more than just a place for technical instruction; it embodied Segal's evolving ideas about the psychological and therapeutic potential of art. Drawing on his own experiences and perhaps influenced by the growing field of psychoanalysis, Segal developed teaching methods aimed at fostering emotional expression and psychological adjustment, particularly for those traumatized by war and displacement.

He worked extensively with refugee children, many of whom had arrived in Britain through the Kindertransport program. Segal believed that the process of creating art could help these children process their experiences, build self-esteem, and develop positive relationships. His approach often involved guiding students through naturalistic studies – still lifes and portraits – not merely as exercises in representation, but as ways to explore the fundamental elements of light, form, and color. He encouraged students to express their inner feelings and subjective responses rather than simply copying reality or illustrating preconceived ideas.

Segal's pioneering work in this area contributed significantly to the early development of art therapy in Britain. His methods emphasized the healing power inherent in the creative process itself. Although not formally trained as a therapist, his intuitive understanding of art's psychological benefits laid groundwork for future practitioners. His legacy also extended through his family; his son, Walter Segal, became a highly respected architect known for his innovative self-build housing methods, carrying forward a spirit of humanistic design and empowerment, arguably influenced by his father's principles of equality and practical creativity.

Artistic Themes and Techniques

Throughout his diverse career, Arthur Segal explored a range of themes and employed various techniques, though certain preoccupations remained constant. His work often engaged with the realities of modern life, reflecting both its dynamism and its anxieties. Social critique and anti-war sentiments are palpable in many of his pieces, particularly his woodcuts, which lent themselves to stark, expressive commentary. Works like the early woodcut Kain und Abel (Cain and Abel) delve into fundamental questions of humanity, violence, and morality, using biblical narrative to address timeless concerns.

While deeply engaged with modernist abstraction and theory, Segal never entirely abandoned representation. His subjects included landscapes, cityscapes, portraits, and still lifes. His unique "prismatic" style, developed in the 1920s, allowed him to integrate representational elements within a highly structured, almost abstract compositional framework. His meticulous exploration of light and color remained central, evolving from early Impressionist concerns to the complex optical harmonies of his Equivalence principle.

Woodcut was a particularly important medium for Segal, alongside painting. He mastered this technique, producing numerous prints known for their strong graphic quality and emotional intensity. This medium aligned well with the Expressionist ethos and allowed for wider dissemination of his images. Even in his later works, such as the painting Natură statică (Still Life) from 1943, created during his final years in London, his enduring interest in form, color, and balanced composition is evident. His technical versatility supported his thematic explorations, ranging from intimate domestic scenes to broader social and philosophical statements.

Legacy and Recognition

Arthur Segal's legacy is multifaceted. He stands as a significant bridge figure in modern art, connecting the emotional intensity of German Expressionism with the conceptual challenges of Dadaism, and synthesizing these influences into a unique artistic vision articulated through his Principle of Equivalence. His co-founding of the Neue Sezession highlights his role as an organizer and advocate for the avant-garde in early 20th-century Berlin. His circle included prominent artists like Kandinsky, Marc, Kirchner, Pechstein, Tzara, Arp, Hausmann, and Höch, placing him firmly within the currents of European modernism.

His contributions extend beyond his own artistic output. As an educator in Berlin and later in London, he influenced generations of students. His pioneering use of art as a therapeutic tool, especially with vulnerable refugee populations, marks him as an important precursor to the field of art therapy. This humanistic dimension of his work adds another layer to his significance.

Despite his active participation in key movements and his distinctive theoretical contributions, Segal's work perhaps did not achieve the same level of widespread fame as some of his contemporaries during his lifetime or immediately after. However, his importance has been increasingly recognized through posthumous exhibitions and scholarly attention. Exhibitions of his work continued after his death in London on June 23, 1944, including showings noted even into 1945 at venues like London's Royal Academy of Arts (though likely as part of larger group shows). Arthur Segal remains a compelling figure whose life and art offer profound insights into the artistic innovations, political upheavals, and enduring human concerns of the first half of the 20th century.