Franz Marc stands as one of the most compelling figures of German Expressionism. Born in Munich in 1880, his life, though tragically cut short by the First World War in 1916, was marked by an intense search for spiritual truth through art. He is best known for his vibrant, emotionally charged paintings of animals, which he saw as symbols of a purer, more harmonious existence than that of humankind. As a principal founder of the influential Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group, Marc, alongside artists like Wassily Kandinsky, sought to infuse art with profound spiritual and emotional resonance, leaving an indelible mark on the course of modern art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Franz Marc's upbringing in Munich provided a fertile ground for his later artistic and spiritual inclinations. His mother, Sophie, instilled in him a deep sense of piety and reverence for the natural world, themes that would echo throughout his artistic career. His father, Wilhelm Marc, was an academic painter, primarily focused on landscapes, providing Franz with an early, albeit traditional, exposure to the practice of painting. This familial environment fostered an appreciation for both nature and art from a young age.

Initially, Marc did not set out to become an artist. His early academic pursuits leaned towards theology and philosophy, reflecting the spiritual searching that would later define his art. However, the call of visual expression proved stronger. He eventually abandoned his theological studies and enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1900. There, he studied under respected, though relatively conservative, painters Gabriel von Hackl and Wilhelm von Diez until 1902. While providing a solid technical foundation, the academic environment ultimately felt restrictive to Marc's burgeoning modern sensibilities.

Crucial to Marc's artistic development were his trips to Paris in 1903 and again in 1907. The French capital was the epicenter of the avant-garde, and Marc absorbed the revolutionary artistic currents swirling around him. He encountered the intense colors and emotional brushwork of Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. He also witnessed the bold chromatic experiments of the Fauves, led by Henri Matisse, and the radical formal deconstruction of early Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. These encounters were transformative, pushing Marc away from academic naturalism towards a more expressive, symbolic, and structurally innovative style.

The Turn to Animals and Color

Returning from Paris, Marc began to solidify his unique artistic vision. Dissatisfied with depicting the human form, which he increasingly saw as flawed and corrupted, he turned his focus almost exclusively to animals. For Marc, animals represented a state of primal innocence, spiritual purity, and a harmonious connection with the natural world that humanity had lost. He sought to depict not just their outward appearance, but their inner essence, their way of experiencing the world – what he termed their "animalization" of art. Horses, deer, cows, and birds became his primary subjects, conduits for exploring themes of vitality, grace, suffering, and the sacredness of creation.

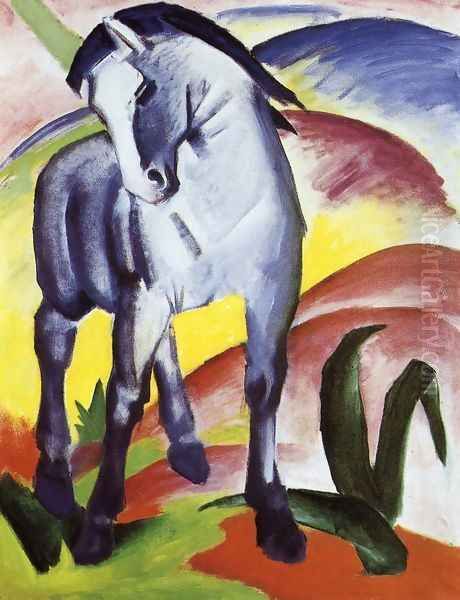

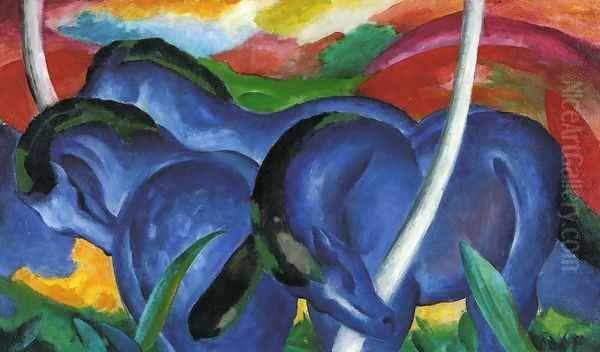

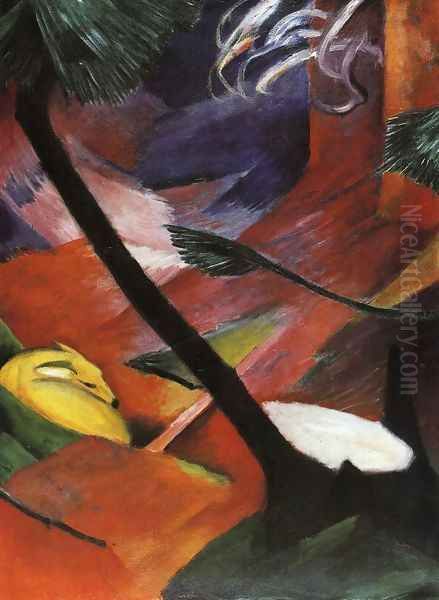

Parallel to his focus on animals, Marc developed a highly personal and symbolic theory of color. Influenced by sources ranging from Goethe's color theory to the expressive potential he saw in artists like Van Gogh and the Fauves, Marc assigned specific emotional and spiritual meanings to primary colors. Blue became associated with the masculine principle, spirituality, and austerity. Yellow represented the feminine principle, gentleness, joy, and sensuality. Red symbolized matter, brutality, violence, and the earth, often carrying a heavy, sometimes ominous weight. Green and violet served as mediating or transitional colors. This deliberate, symbolic use of color became a hallmark of his work, allowing him to imbue his animal portraits with profound emotional depth and spiritual resonance.

The Blue Rider: Collaboration and Vision

Marc's search for like-minded artists led him to connect with the burgeoning avant-garde scene in Munich, particularly the circle around the Russian émigré artist Wassily Kandinsky. In 1909, Marc joined the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM, or New Artists' Association of Munich), a group co-founded by Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, Gabriele Münter, and others, aiming to promote more progressive art forms. However, artistic differences and internal tensions soon arose within the NKVM. Kandinsky's increasingly abstract work faced resistance from more conservative members.

The breaking point came in late 1911 when a painting by Kandinsky was rejected from the NKVM's third exhibition. In protest, Kandinsky, Marc, Münter, and Alfred Kubin resigned. Almost immediately, Marc and Kandinsky organized a counter-exhibition under a new banner: Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). The name, famously chosen over coffee, reflected Marc's love of horses and blue, and Kandinsky's recurring motif of the rider, often symbolizing the spiritual journey. August Macke, a close friend of Marc's with a distinctively lyrical style influenced by French modernism, quickly became another key figure in the group.

Der Blaue Reiter was less a formal movement with a strict manifesto and more a loose association of artists united by a shared belief in the spiritual dimension of art and the need for creative freedom. They sought an art that transcended mere representation to express inner truths and emotions. Their vision was international and inclusive, embracing diverse influences from folk art, children's drawings, medieval German woodcuts, and non-European art, alongside contemporary avant-garde developments like Fauvism and Cubism.

A cornerstone of their activity was the publication of the Der Blaue Reiter Almanac in May 1912. Co-edited by Kandinsky and Marc, this seminal publication was a compendium of essays, musical scores, and reproductions showcasing the group's eclectic interests. It featured contributions not only from visual artists like Marc, Kandinsky, Macke, Münter, Henri Rousseau, Robert Delaunay, and Arnold Schoenberg (who was also a painter), but also essays on music (including Schoenberg's theories) and theater. The Almanac aimed to demonstrate the interconnectedness of the arts and their shared capacity for spiritual expression.

The group organized two landmark exhibitions. The first, held in December 1911 concurrently with the rejected NKVM show, featured works by 14 artists, including Marc, Kandinsky, Macke, Münter, Delaunay, Rousseau, and Schoenberg. The second exhibition, focused on works on paper, followed in early 1912 and was even broader, including artists like Paul Klee, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Kazimir Malevich, and members of the Dresden-based Expressionist group Die Brücke (The Bridge), such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel. These exhibitions and the Almanac cemented Der Blaue Reiter's position at the forefront of the European avant-garde, championing abstraction and spiritual expression in art. Other artists closely associated with the circle included Heinrich Campendonk and the Burliuk brothers.

Marc's Mature Style: Expressionism and Abstraction

The period between 1911 and 1914 marked the apex of Franz Marc's artistic development. His style became increasingly bold, abstract, and spiritually charged. He fully integrated the lessons of Fauvism in his use of intense, non-naturalistic color, and absorbed the structural innovations of Cubism and Futurism, particularly the dynamic fragmentation of form associated with Robert Delaunay's Orphism, which Marc encountered during a trip to Paris with August Macke in 1912. Delaunay's prismatic colors and simultaneous views deeply influenced Marc's later work.

During these years, Marc created many of his most iconic paintings. Works like Blue Horse I (1911) and the group composition The Large Blue Horses (1911) exemplify his use of blue to convey spirituality and tranquility, presenting the animals with monumental grace. The Yellow Cow (1911) bursts with joyful energy, its vibrant yellow embodying feminine vitality against a richly colored, abstracted landscape. Tiger (1912) uses Cubist-inspired geometric planes and clashing colors to depict the animal's raw power and energy.

His compositions became more complex and dynamic. In paintings like Deer in the Forest I (1913) and Deer in the Forest II (1914), the animals are almost woven into the fabric of the landscape, their forms fractured and fused with the surrounding trees and light, rendered in crystalline, jewel-like facets of color. This approach reflected Marc's pantheistic belief in the unity of all creation and his attempt to visualize the underlying rhythms and structures of nature. He sought to paint the world as the animal might perceive it, breaking down conventional perspectives.

As Europe edged closer to war, a sense of unease and impending doom began to permeate Marc's work. This is powerfully evident in Fate of the Animals (Tierschicksale, 1913). This large, apocalyptic canvas depicts a forest consumed by fire and destruction, with terrified animals caught in the chaos. Shards of color and fragmented forms convey violence and terror. Marc himself described the painting as a premonition of war, writing on the back, "And all being is flaming suffering." It remains one of the most potent expressions of anxiety in early 20th-century art.

His final major works, such as Fighting Forms (1914) and the sketches for Tower of Blue Horses (1913, painting now lost), pushed further towards complete abstraction. Fighting Forms presents a swirling vortex of clashing red and black shapes against cooler blues, representing cosmic forces or spiritual struggle rather than recognizable objects. Though still rooted in his observation of nature, Marc was moving towards an art of pure form and color, akin to the path Kandinsky was forging, but always retaining a connection to the organic world.

War, Premonition, and Tragedy

Like many artists and intellectuals of his generation across Europe, Franz Marc initially greeted the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 with a degree of patriotic fervor and misplaced idealism. He saw the war, tragically, as a necessary cataclysm that could potentially purify a materialistic and spiritually bankrupt Europe, paving the way for renewal. He volunteered for service in the German army almost immediately.

His experiences at the front, however, quickly tempered any romantic notions about warfare. His letters from the field reveal growing disillusionment and horror at the industrialized slaughter. Yet, even amidst the brutality, he continued to sketch and reflect on art, seeking spiritual solace and contemplating the future of European culture. He even worked on camouflage techniques, painting abstract patterns onto tarpaulins to conceal artillery – a grimly ironic application of avant-garde aesthetics.

Recognizing the value of prominent artists, the German government began identifying individuals to be withdrawn from combat duty. Marc's name was on this list. Tragically, before the orders could reach him, he was struck in the head by a shell fragment during reconnaissance near Verdun, France. Franz Marc died instantly on March 4, 1916. He was only 36 years old. His death, along with the earlier death of his close friend August Macke near the start of the war in September 1914, represented a devastating loss for German art and the Der Blaue Reiter circle, which effectively ceased to exist with the onset of the conflict and the dispersal of its members.

Legacy and Influence

Despite his short life, Franz Marc's impact on modern art was profound. He remains a central figure of German Expressionism, celebrated for his unique synthesis of vibrant color, animal symbolism, and spiritual searching. His work offered a powerful alternative to purely formal abstraction, grounding emotional and spiritual expression in the perceived purity of the natural world. His color theory, though personal, contributed significantly to the Expressionist exploration of color's psychological and symbolic potential, influencing contemporaries and later artists.

The fate of Marc's work after his death reflects the turbulent history of the 20th century. During the Nazi regime in the 1930s and 1940s, his art, along with that of most modern artists like Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Oskar Kokoschka, Paul Klee, and Kandinsky, was deemed "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst). Approximately 130 of his works were confiscated from German museums. Many were sold abroad, while others were tragically destroyed. His monumental Tower of Blue Horses, one of his most ambitious late works, was prominently displayed in the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition in Munich in 1937 before disappearing; its fate remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of lost art, likely destroyed in the war's final days or hidden in a private collection.

In the post-war era, Marc's reputation was restored, and his work became highly sought after. However, the legacy of Nazi looting continues to cast a shadow. Restitution cases involving his paintings, such as Red Deer II, occasionally surface, highlighting the complex provenance issues surrounding art displaced during that dark period. Museums and collections worldwide now proudly display his paintings, recognizing their beauty and historical significance.

Franz Marc's enduring appeal lies in the emotional intensity and spiritual sincerity of his vision. He successfully fused the formal innovations of the European avant-garde with a deeply personal, almost mystical reverence for nature. His paintings of animals, rendered in luminous, symbolic colors and increasingly abstract forms, continue to resonate with viewers, offering a glimpse into a world imbued with spiritual harmony and primal energy, a poignant counterpoint to the complexities and anxieties of modern existence. His tragically short career stands as a testament to the power of art to explore the deepest connections between humanity, nature, and the spirit.

Conclusion

Franz Marc's journey from aspiring theologian to a leading light of the Expressionist avant-garde encapsulates a pivotal moment in modern art history. Driven by a profound spiritual yearning and a unique empathy for the animal world, he forged a distinctive artistic language characterized by symbolic color, dynamic forms, and emotional depth. His collaboration with Wassily Kandinsky in founding Der Blaue Reiter created a vital platform for artists seeking to transcend materialism and explore the inner life through art. Though his life was cut short on the battlefields of Verdun, Marc left behind a body of work that continues to captivate with its vibrant beauty and its poignant exploration of nature's soul. He remains an essential figure for understanding German Expressionism and the enduring quest for spiritual meaning in modern art.