Robert Bereny stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art. A Hungarian painter and graphic designer, Bereny was instrumental in bringing the revolutionary ideas of modern art, particularly Expressionism and Cubism, to his homeland. His life and career were deeply intertwined with the turbulent political and cultural shifts of his time, leading to periods of intense creativity, political engagement, exile, and eventual rediscovery. As a core member of the influential avant-garde group "The Eight" (Nyolcak), Bereny helped shape the course of Hungarian modernism, leaving behind a body of work characterized by bold experimentation, emotional depth, and a distinctive graphic sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

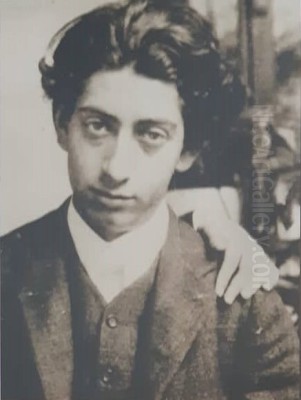

Born in Budapest in 1887, Robert Bereny embarked on his artistic journey during a period of burgeoning cultural change across Europe. His initial formal training was brief, studying under the Hungarian painter Tivadar Zemplényi. However, like many ambitious young artists of his generation, Bereny soon recognized that Paris was the epicenter of artistic innovation. He traveled to the French capital in the early 1900s to immerse himself in its vibrant art scene.

Paris proved to be a crucible for Bereny's developing style. He attended the Académie Julian, a popular destination for foreign artists. More importantly, he encountered the groundbreaking work of Post-Impressionist masters, particularly Paul Cézanne. Cézanne's structural approach to form, his emphasis on underlying geometric shapes, and his method of building compositions through planes of color left an indelible mark on Bereny, as it did on countless other modernists, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque who were simultaneously forging Cubism. The Fauvist explosion of color, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, also likely contributed to the bold palette Bereny would later employ.

The Eight (Nyolcak): Forging a Hungarian Avant-Garde

Upon returning to Budapest, Bereny brought with him the radical ideas fermenting in Paris. He found kindred spirits among a group of progressive Hungarian artists eager to break away from the prevailing academic traditions and naturalist styles. In 1909, Bereny became a founding member of "The Eight" (Nyolcak), arguably the most important avant-garde group in early 20th-century Hungarian art history.

Alongside Bereny, The Eight included Károly Kernstok (often seen as the group's leader), Dezső Czigány, Béla Czóbel, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pór, and Lajos Tihanyi. This collective shared a commitment to embracing modern European artistic trends, primarily French Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the nascent Cubist movement. They sought to synthesize these international influences with a unique Hungarian sensibility, often imbued with a strong sense of social awareness and psychological depth.

The Eight held landmark exhibitions, notably in 1909 and 1911, which shocked the conservative Budapest art establishment but announced the arrival of a powerful new artistic force. Their work emphasized subjective experience, bold color, simplified forms, and a departure from illusionistic representation. Bereny was a central figure in the group, contributing paintings that exemplified their shared goals while showcasing his developing personal style, which increasingly fused Expressionist intensity with Cubist structural elements. The group, though relatively short-lived in its initial formation, had a profound and lasting impact, paving the way for subsequent avant-garde movements in Hungary, such as Activism, associated with figures like Lajos Kassák.

Bereny's Artistic Style: Expressionism, Cubism, and Synthesis

Robert Bereny's mature style is best characterized by its dynamic synthesis of Expressionism and Cubism. He absorbed the lessons of Cézanne regarding structure and form, but filtered them through an Expressionist lens that prioritized emotional impact and subjective interpretation. Unlike the more analytical approach of Parisian Cubists like Picasso and Braque, Bereny's fragmentation of form often served to heighten the psychological tension or dynamism of the subject.

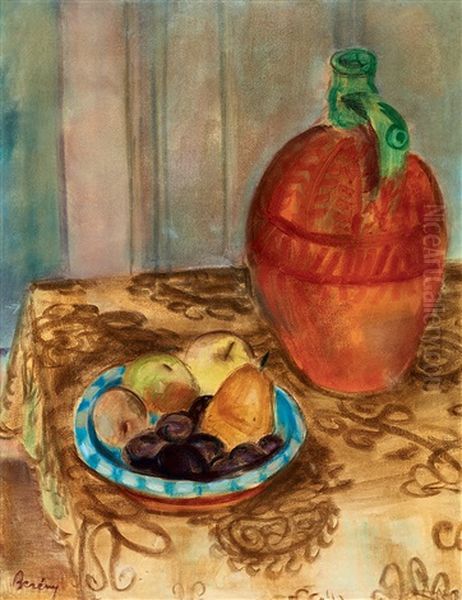

His palette could be vibrant and Fauvist-inspired, employing strong, often non-naturalistic colors to convey feeling. Yet, he also demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of color harmony and tonal relationships. His compositions are typically energetic, utilizing diagonal lines, fragmented planes, and a sense of movement that engages the viewer directly. He applied this approach to various genres, including portraits, still lifes, and figure compositions.

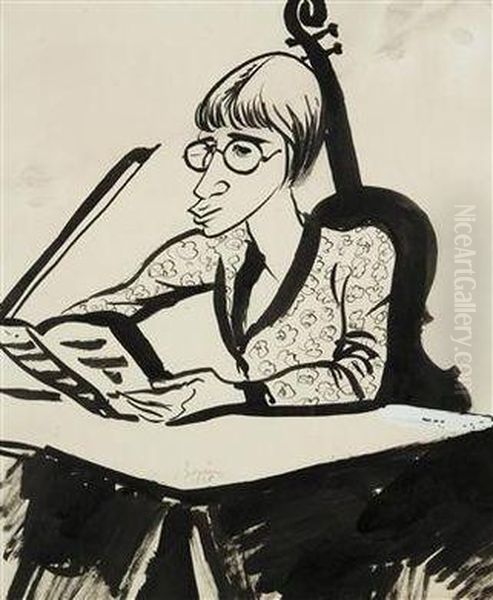

A quintessential example of his style is the painting Cellist (sometimes dated around 1928, though stylistic elements appear earlier). Here, the figure of the musician and the instrument are broken down into geometric facets, yet the overall impression is one of intense concentration and the emotional resonance of music. The colors are rich and applied in bold patches, contributing to the work's expressive power. It clearly shows the influence of Cubism in its formal language but retains an emotional core characteristic of Expressionism, perhaps echoing the intensity found in German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Emil Nolde, though developed independently.

Modernist Poster Design

Beyond his work as a painter, Robert Bereny made significant contributions to the field of graphic design, particularly modernist poster art. During the early 20th century, the poster emerged as a vital medium for communication and artistic expression, and Hungary developed a vibrant poster tradition. Bereny became one of its leading exponents, creating designs that were both commercially effective and artistically innovative.

His poster work often reflects the same principles seen in his paintings: bold simplification of form, dynamic composition, and a strong sense of graphic clarity. He skillfully integrated typography with imagery, creating cohesive and eye-catching designs. One of his most celebrated series of posters was created for the Modiano cigarette paper company. These designs often feature striking geometric arrangements, flat planes of color, and stylized figures, embodying the clean lines and functional aesthetic associated with emerging modernist design principles, distantly echoing the ethos that would later be formalized by the Bauhaus school under Walter Gropius.

Bereny's posters stand alongside the work of other notable Hungarian poster artists of the era, such as Mihály Bíró, Imre Földes, and Géza Faragó. His designs are recognized for their unique blend of avant-garde aesthetics – incorporating elements of Cubism, Expressionism, and sometimes Art Deco – with the demands of commercial advertising. They represent a significant chapter in Hungarian graphic design history, demonstrating how modernist art principles could be effectively applied to mass communication.

Political Engagement: The Hungarian Soviet Republic and Exile

Bereny's life took a dramatic turn with the political upheavals following World War I. He became actively involved in the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, a communist state that lasted only 133 days. During this period, many avant-garde artists, including Bereny and members of the Activist group like Béla Uitz, aligned themselves with the revolutionary government, seeing it as an opportunity to implement radical social and cultural changes.

Bereny took on an official role within the Republic's Art Directorate, serving as the head of its painting department. He dedicated his artistic skills to the revolutionary cause, most famously creating the powerful recruitment poster To Arms! To Arms! (Fegyverbe! Fegyverbe!). This iconic image, depicting a determined sailor pointing forward against a stark red background, became one of the defining visual symbols of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Its urgent message and bold, simplified design made it highly effective propaganda.

However, the collapse of the Soviet Republic in August 1919 had severe consequences for those associated with it. Facing political persecution under the subsequent counter-revolutionary regime, Bereny was forced to flee Hungary. He emigrated, spending several years in exile, primarily in Berlin. Berlin during the Weimar Republic was a major center for exiled artists and intellectuals and a hub of artistic ferment, home to German Expressionism, Dada (with figures like Raoul Hausmann), and the burgeoning Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). While details of his specific activities in Berlin are less documented, this period undoubtedly exposed him to further currents in European modern art.

Return to Hungary and Later Career

Around 1926, Robert Bereny returned to Hungary. The political climate remained challenging, and the avant-garde spirit of the pre-war and revolutionary years had somewhat dissipated. He resumed his career as a painter and designer, though likely facing difficulties due to his past political affiliations and the generally conservative cultural atmosphere.

His later work continued to evolve, though perhaps with less of the overt radicalism of his earlier periods. He continued to paint portraits, landscapes, and still lifes, often retaining elements of his Expressionist and Cubist foundations but perhaps integrating them into a more subtly modulated style. Despite the hardships, he remained a dedicated artist, continuing to produce work and exhibit when possible. He taught art and maintained connections within the Budapest art scene. His earlier contributions, particularly his role in The Eight and his iconic poster designs, ensured his place in the annals of Hungarian art history, even if contemporary recognition fluctuated.

The Curious Case of the Sleeping Lady with Black Vase

One of the most fascinating episodes related to Robert Bereny occurred long after his death in 1953. It involves the rediscovery of a lost masterpiece in the most unlikely of places: a Hollywood family film. His painting, Sleeping Lady with Black Vase, created in the late 1920s, had disappeared from view, likely taken out of Hungary before or during World War II, and was presumed lost.

In 2009, Gergely Barki, an art historian and researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery, was watching the 1999 movie Stuart Little with his daughter. To his astonishment, he spotted what he immediately recognized as Bereny's lost painting hanging on the wall in the background of the Little family's home. Barki embarked on a quest to track down the painting. His investigation revealed that an assistant set designer for the film had purchased the artwork cheaply from an antique shop in Pasadena, California, unaware of its significance, simply because she liked its avant-garde style for the set.

After contacting Sony Pictures and Columbia Pictures, Barki eventually connected with the set designer who still owned the painting. The work was authenticated, and its incredible journey back into the public eye began. In 2014, Sleeping Lady with Black Vase was repatriated to Hungary and put up for auction in Budapest. It sold for a remarkable €229,500 (approximately $285,700 at the time), significantly exceeding its estimate and confirming the high regard for Bereny's work. This extraordinary story of loss and rediscovery brought international attention to Robert Bereny and highlighted the unpredictable ways in which art history can unfold.

Collaborations, Contemporaries, and Context

Robert Bereny's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships and influences. His most significant collaboration was undoubtedly with the members of The Eight (Kernstok, Czigány, Czóbel, Márffy, Orbán, Pór, Tihanyi). This group provided a crucial platform for mutual support, intellectual exchange, and the promotion of modernism in Hungary.

He also interacted with other key figures of the Hungarian avant-garde, including Lajos Kassák, the central figure of the Activist movement, and Béla Uitz, with whom he collaborated in educational initiatives during the Soviet Republic. Later sources mention collaborations with figures like Marianne Brandt (known for her Bauhaus metalwork, suggesting possible connections to broader design circles) and István Sebő, though details might be sparse.

On the international stage, Bereny's work engaged with the major currents of his time. His debt to Cézanne is clear. His work can be seen in dialogue with French Fauvism (Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck) and Cubism (Picasso, Braque, perhaps Fernand Léger). While developing his own distinct style, his art shares the era's preoccupation with form, color, and subjective expression seen also in German Expressionism (Kirchner, Nolde, Franz Marc, Wassily Kandinsky) and even certain aspects of Italian modernism (perhaps the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, in terms of mood, though stylistically different). He was a participant in the broad sweep of European modernism, adapting international trends to a Hungarian context. His contemporaries in Hungary included established figures moving towards modernism like József Rippl-Rónai and unique talents like Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka, painting a diverse picture of Hungarian art at the turn of the century.

Legacy and Market Reception

Robert Bereny's legacy is multifaceted. He is recognized as a pioneer of Hungarian modernism, a key member of the influential group The Eight, and an artist who successfully bridged painting and graphic design. His work introduced and adapted major European avant-garde styles for a Hungarian audience, contributing significantly to the nation's cultural identity in the 20th century. His political engagement during the Hungarian Soviet Republic, particularly his poster "To Arms!", cemented his place in the country's political and visual history.

The rediscovery and subsequent high-profile auction of Sleeping Lady with Black Vase significantly boosted Bereny's international profile and market value in the 21st century. His works now command substantial prices at auction, reflecting a growing appreciation for his artistic quality and historical importance. Both his paintings, like the expressive Cellist, and his modernist posters, such as the Modiano series, are sought after by collectors and institutions.

Art historians continue to study his contribution, placing him within the complex narrative of Central European modernism, a region whose artistic achievements were often overshadowed by events in Paris or Berlin, or obscured by the political turmoil of the 20th century. Bereny's work stands as testament to the vibrancy and originality of the Hungarian avant-garde.

Conclusion

Robert Bereny's artistic journey mirrors the dramatic arc of the early 20th century. From the heady innovations of pre-war Paris to the revolutionary fervor of 1919, through exile and a return to a changed homeland, his art consistently engaged with the leading ideas of modernism. As a painter, he forged a powerful synthesis of Expressionist feeling and Cubist structure. As a graphic designer, he created iconic posters that captured the spirit of his time. A founding member of The Eight, he helped steer Hungarian art in a bold new direction. Though his career faced interruptions and his name was perhaps less known internationally than some contemporaries for many years, the rediscovery of lost works and continued scholarly interest have reaffirmed Robert Bereny's status as a crucial and compelling figure in the history of Hungarian and European modern art. His work continues to resonate through its visual power, emotional depth, and historical significance.