Arthur von Ferraris (1856-1936) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Hungarian-born Austrian painter, he became renowned for his meticulous and evocative Orientalist scenes, as well as his society portraits. His life and career spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and socio-political upheaval, from the height of academic classicism to the dawn of modernism, and through the tumultuous years leading up to and following the First World War. Ferraris navigated these currents, carving out a distinct niche with his technical brilliance and keen observational eye, particularly for the cultures of the Near East.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Galkovitz, Hungary, then part of the Austrian Empire, in 1856, Arthur Lajos von Ferraris (originally Fejérváry) grew up in a region still echoing with the reverberations of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. While he was too young to have directly witnessed these events, the historical context of a resurgent Habsburg dynasty and the complex national identities within the Empire would have formed the backdrop of his formative years. His family's noble status, indicated by the "von," likely afforded him opportunities for education and cultural exposure.

His artistic inclinations led him to Vienna, the imperial capital and a major cultural hub. There, he undertook his initial artistic training under the tutelage of Joseph Matthaus Aigner (1818-1886), a respected Austrian portrait painter known for his Biedermeier style and later, more official portraits, including several of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Aigner's instruction would have grounded Ferraris in the fundamentals of academic drawing and painting, particularly in capturing a likeness, a skill that would serve him well throughout his career.

Seeking to further refine his talents and immerse himself in the leading art scene of the era, Ferraris moved to Paris in 1876. This was a pivotal decision. Paris was the undisputed center of the art world, home to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts and the influential annual Salons. He enrolled at the École, where he studied under some of the most celebrated academic painters of the time.

His most significant mentors in Paris were Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) and Jules Joseph Lefebvre (1836-1911). Gérôme was a towering figure in French academic art, renowned for his historical paintings, Greek and Roman scenes, and, crucially for Ferraris's later development, his highly detailed and polished Orientalist works. Gérôme's influence on Ferraris cannot be overstated; the meticulous attention to detail, the smooth finish, and the ethnographic interest in the "Orient" are all hallmarks that Ferraris would adopt and adapt. Lefebvre, another prominent academician, was celebrated for his idealized female nudes and portraits, and his emphasis on precise draughtsmanship and elegant composition would also have contributed to Ferraris's technical mastery. Other notable figures at the École or in the Parisian academic scene at the time included William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, whose polished styles dominated the Salons.

The Allure of the Orient: Travels and Thematic Development

The late 19th century was the zenith of Orientalism in European art. Fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, and a romantic fascination with cultures perceived as exotic and unchanging, artists flocked to North Africa, the Levant, and the Ottoman Empire. Gérôme himself was a pioneer in this, undertaking extensive travels and bringing back sketches and artifacts that informed his studio productions. It was almost inevitable that a student of Gérôme with an adventurous spirit would be drawn to these lands.

Ferraris embarked on several journeys to the East, notably to Egypt and Turkey, and possibly other parts of North Africa and the Middle East. These travels were not mere tourist excursions but vital research expeditions. He immersed himself in the local cultures, sketching street scenes, architectural details, marketplaces, and the diverse inhabitants. He collected textiles, costumes, and objects that would later populate his canvases, lending them an air of authenticity that was highly prized by contemporary audiences.

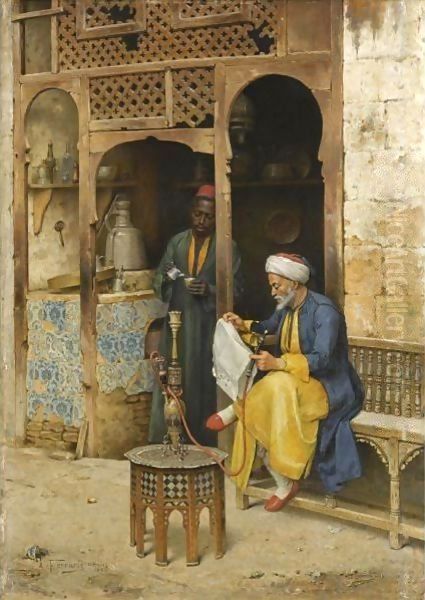

His experiences in cities like Cairo and Constantinople (Istanbul) provided a rich seam of subject matter. He was captivated by the daily life, the interplay of light and shadow in narrow souks, the quiet dignity of scholars in mosques, the vibrant attire of market vendors, and the secluded world of the harem, a perennially popular, if often fantasized, Orientalist theme. Unlike some Orientalists who focused on grand historical narratives or overtly sensualized depictions, Ferraris often gravitated towards more intimate, ethnographic scenes, capturing moments of everyday life with a sympathetic, if still romanticized, eye. His approach combined the detailed realism learned from Gérôme with a sensitivity to atmosphere and character.

Masterpieces and Signature Style

Arthur von Ferraris's oeuvre is characterized by its technical polish, meticulous detail, and a focus on both Orientalist genre scenes and society portraiture. His training under Aigner, Gérôme, and Lefebvre instilled in him a profound respect for academic principles, which he skillfully applied to his chosen subjects.

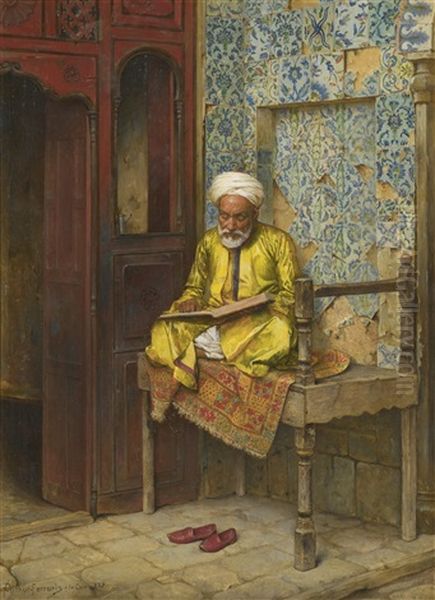

One of his most celebrated and representative Orientalist works is The Scholar of Cairo (also known as A Scholar in Cairo or Learned Man of Cairo), painted around 1886. This painting exemplifies his mature style. It depicts an elderly scholar, possibly an Imam or teacher, seated on a carpet in a sunlit interior, deeply engrossed in a large manuscript. The details are rendered with almost photographic precision: the intricate patterns of the carpet and wall hangings, the texture of the scholar's robes, the aged paper of the book, and the play of light filtering into the room. The composition is balanced, and the figure exudes a sense of quiet contemplation and intellectual depth. Such works appealed to a European audience fascinated by the perceived wisdom and timeless traditions of the East. The painting showcases Ferraris's mastery of light, texture, and ethnographic detail, hallmarks of Gérôme's school.

Another notable work, The Clever Monkey (1892), demonstrates a different facet of his Orientalist repertoire, incorporating a touch of anecdotal charm. While the exact subject might vary in interpretation, such scenes often involved street entertainers or domestic settings where animals played a role, adding a picturesque element. This painting was exhibited in the Budapest Salon and helped re-establish his connections with his native Hungary.

His travels also yielded numerous other scenes of marketplaces, street vendors, guards, and domestic interiors. Works like Nubian Lady (1894) showcase his skill in portraying diverse ethnicities with attention to costume and physiognomy. He was adept at capturing the textures of rich fabrics, gleaming metalwork, and ancient stonework, creating a tangible sense of place. His palette, while often rich, was controlled, emphasizing realism over impressionistic effects, though he was certainly aware of the Impressionist movement flourishing during his time in Paris. His style, however, remained firmly rooted in the academic tradition, valuing finish and clarity.

Beyond Orientalist subjects, Ferraris was also an accomplished portrait painter. His society portraits were sought after by a distinguished clientele, which reportedly included prominent figures such as the American industrialist John D. Rockefeller, the financier Davidson Phillips, and even, according to some sources, the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. These commissions attest to his reputation and his ability to capture not only a likeness but also the status and personality of his sitters. A work like Young Woman in a White Dress (1881) demonstrates his early prowess in portraiture, showcasing elegant handling of fabric and a sensitive portrayal of the subject.

A European Career: Exhibitions, Recognition, and Artistic Circles

Ferraris actively pursued a career that transcended national borders. After his formative years in Vienna and Paris, he continued to exhibit widely across Europe and even in the United States. His works were regularly accepted at the prestigious Paris Salon, a key venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. He also showed his paintings in major art centers such as Berlin, Düsseldorf, Munich, and Vienna, as well as New York. This international exposure helped solidify his reputation as a leading Orientalist painter of his generation.

His success was not limited to exhibitions. Ferraris received several awards and honors for his work, though specific details of these can be somewhat elusive in historical records. The very fact that he secured commissions from high-profile individuals indicates the esteem in which he was held.

In Vienna, Ferraris became associated with the Vienna Secession (Wiener Secession), a movement founded in 1897 by a group of Austrian artists, including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, and Joseph Maria Olbrich. The Secessionists had broken away from the conservative Association of Austrian Artists, advocating for artistic freedom, a broader definition of art, and greater exposure to international contemporary art. Ferraris's involvement, reportedly as a member from 1898, suggests a progressive outlook and a desire to engage with the evolving art scene, even if his own style remained relatively traditional compared to the Art Nouveau tendencies of many Secessionists. His participation likely reflected a shared belief in the importance of artistic innovation and independence from academic constraints, even as he himself was a product of that academic system.

He also maintained connections with other artists. During his time in Paris, he is said to have shared a studio for a period in the late 1880s with Charles Wilda (1854-1907), another Austrian Orientalist painter. Wilda, like Ferraris, was known for his detailed depictions of life in Cairo. Such studio-sharing arrangements were common and fostered artistic exchange and camaraderie. Another prominent Austrian Orientalist contemporary was Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935), who also studied in Vienna and Paris (under Jean-Paul Laurens) and became highly successful with his meticulously rendered scenes of Cairo. While direct collaborations might be hard to pinpoint, Ferraris, Deutsch, and Wilda formed part of a significant contingent of Austro-Hungarian artists contributing to the Orientalist genre, often sharing thematic interests and a commitment to detailed realism. Rudolf Ernst (1854-1932), another Viennese-born Orientalist active in Paris, also explored similar themes with a comparable level of detail, focusing on tile-work, guards, and scholarly figures.

The competitive landscape of the Orientalist market was robust. Artists like Jean Discart, a French-Italian painter, and Frederick Arthur Bridgman, an American pupil of Gérôme, were also producing popular scenes of North African life. In Britain, painters like John Frederick Lewis (who lived in Cairo for many years), David Roberts (known for his topographical views), and Edwin Lord Weeks (an American who traveled extensively) were major figures. The Italian Orientalists, such as Alberto Pasini and Giulio Rosati, also contributed vibrant and detailed market scenes and depictions of Arab horsemen. Ferraris operated within this international milieu, distinguishing himself through his consistent quality and particular focus.

Beyond the Canvas: Anecdotes and Personal Life

While much of Arthur von Ferraris's life is understood through his artistic output, a few intriguing details about his personal interests have survived. One of the most notable is his passion for philately. He was reportedly an avid and serious stamp collector, with a particular interest in rare and valuable specimens. Sources mention his acquisition of significant collections, including the renowned "Rothschild" and "Cooper" collections, and his possession of rarities like the "Blue Mauritius" and British Guiana stamps. There were even reports of his intention to donate his valuable collection to the Berlin Post Office Museum, indicating the seriousness of his pursuit and a philanthropic inclination. This hobby offers a glimpse into a meticulous and discerning mind, qualities also evident in his painting.

His personal life, including details about his family or marriage, remains less documented in readily available art historical sources. The "von" in his name suggests a noble lineage, which might have facilitated his entry into certain social circles and provided a degree of financial stability, although artists, even successful ones, often faced fluctuating fortunes.

The political assertion that Ferraris shifted his stance from supporting "Anglo-American imperialism" to backing the Entente during wartime is a specific claim that requires careful contextualization. Artists, like all citizens, were affected by the geopolitical currents of their time, especially during the cataclysm of World War I. Vienna was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a Central Power, so a shift to supporting the Entente (Britain, France, Russia) would have been a significant and potentially risky personal and political realignment. While his Vienna Secession membership indicates a progressive artistic stance, more concrete evidence would be needed to fully substantiate such a dramatic political shift and its impact on his life or career. It is more broadly understood that the war profoundly disrupted artistic life across Europe, impacting patronage, travel, and the availability of materials.

The "fluidity" of his movements and the resulting "blanks" in his biographical record, as mentioned in some summaries, are not uncommon for artists of that era who traveled extensively or whose personal papers have not been systematically preserved or studied. His death in 1936 occurred as Europe was heading towards another major conflict, and the interwar period was one of significant change in the art world, with modernism largely eclipsing traditional academic styles.

Later Years, Death, and Artistic Legacy

Arthur von Ferraris continued to paint into the early 20th century, though the peak of Orientalism as a popular genre had passed by the First World War. The war itself changed European sensibilities, and the romanticized visions of the East began to fade, replaced by new artistic concerns and movements like Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Academic realism, while still practiced, no longer held the dominant position it once had.

Despite these shifts, Ferraris's work retained its appeal for certain collectors. He passed away in 1936, reportedly in Vienna, though the exact date and circumstances are sometimes cited as uncertain. By this time, the world he had so meticulously depicted in his Orientalist paintings was also undergoing profound transformations.

The artistic legacy of Arthur von Ferraris is primarily tied to his contributions to Orientalist painting. He was a master of academic technique, capable of rendering scenes with extraordinary detail and a refined sense of composition and color. His works offer a window into the European fascination with the Middle East and North Africa during the late 19th century, reflecting both the ethnographic interests and the romanticized perceptions of the era.

In the context of his teachers, particularly Jean-Léon Gérôme, Ferraris can be seen as a faithful and skilled inheritor of a specific tradition of detailed, polished Orientalism. Alongside contemporaries like Ludwig Deutsch and Charles Wilda, he helped to define a particular Austro-Hungarian and Parisian school of Orientalist painting. His works are valued today for their technical excellence and as historical documents, albeit ones filtered through a European lens.

While some critics of Orientalism, notably Edward Said, have pointed to the ways in which such art contributed to colonialist power dynamics and perpetuated stereotypes, the paintings themselves remain objects of beauty and intricate craftsmanship. Ferraris's depictions, often focusing on scholarly pursuits or moments of quiet dignity, tend to be less overtly sensationalized than some of his contemporaries, though they still operate within the broader conventions of the genre.

His society portraits also form an important part of his legacy, demonstrating his versatility and skill in capturing the likeness and character of his sitters. The fact that he attracted high-status patrons speaks to his contemporary reputation.

Today, Arthur von Ferraris's paintings can be found in private collections and occasionally appear in museum exhibitions focusing on 19th-century academic art or Orientalism. Auction prices for his works, particularly his detailed Orientalist scenes, reflect a continued appreciation for his skill and the enduring appeal of the genre. He remains a significant representative of a specific moment in art history, a skilled practitioner whose canvases transport viewers to the bustling souks, quiet courtyards, and scholarly enclaves of a bygone era, all rendered with the meticulous precision of a master craftsman. His dedication to his art, his international career, and his engagement with the artistic currents of his time secure his place in the annals of European painting.