Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928) stands as one of the most prominent American painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, celebrated particularly for his captivating and meticulously detailed Orientalist scenes. Born in Tuskegee, Alabama, Bridgman's artistic journey took him from the burgeoning art scene of New York to the prestigious ateliers of Paris and the sun-drenched landscapes of North Africa. His work, characterized by technical brilliance, vibrant color, and a keen observational eye, brought the exotic allure of the "Orient" to Western audiences, earning him considerable fame and recognition during his lifetime. While his popularity waned with the rise of Modernism, recent scholarship has re-evaluated his contributions, acknowledging him as a significant figure in both American art and the Orientalist movement.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Frederick Arthur Bridgman was born on November 10, 1847, in Tuskegee, Alabama. Following the death of his father when he was just a young child, his family relocated, eventually settling in New York City. This move proved pivotal for the young Bridgman, placing him in a rapidly growing cultural hub. His artistic inclinations manifested early, and by 1864, he was apprenticed as an engraver at the American Bank Note Company. This training, demanding precision and a steady hand, undoubtedly honed his drafting skills, which would become a hallmark of his later paintings.

While working as an engraver, Bridgman pursued formal art education in his spare time. He attended classes at the Brooklyn Art Association and later at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York. These institutions provided him with foundational training in drawing and painting, exposing him to the academic traditions prevalent at the time. Even in these early years, his talent was evident, and he began to exhibit his work, signaling his ambition to become a professional artist. The artistic environment in New York, though developing, still looked to Europe, particularly Paris, as the epicenter of artistic innovation and training.

The Parisian Crucible: Training under Gérôme

In 1866, at the age of nineteen, Bridgman made the transformative decision to move to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. This was a common path for ambitious American artists seeking to refine their skills and gain international recognition. He initially sought out the guidance of various masters but soon enrolled in the atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École des Beaux-Arts. Gérôme was one of the most famous and influential academic painters of his era, renowned for his historical scenes, Greek and Roman subjects, and, crucially for Bridgman's future, his Orientalist paintings.

Studying under Gérôme was an exacting experience. Gérôme emphasized meticulous draftsmanship, a smooth, polished finish, and historical or ethnographic accuracy in his compositions. His own Orientalist works, such as "The Snake Charmer" or "The Prisoner," were celebrated for their detailed realism and exotic subject matter, often based on his own travels to Egypt and the Near East. Bridgman absorbed these lessons thoroughly, developing a technical proficiency that would allow him to render complex scenes with remarkable clarity. The influence of Gérôme is palpable in Bridgman's early Salon entries, demonstrating a shared commitment to academic precision and engaging narrative. Other prominent artists of the academic tradition, like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, also dominated the Salons, setting a high bar for technical skill.

The Allure of the "Orient": Travels and Inspirations

While Paris provided the training, it was Bridgman's travels to North Africa that truly ignited his artistic imagination and defined his career. His first significant journey occurred in the winter of 1872-1873, when he visited Egypt and Algeria. This experience was a revelation. He was captivated by the brilliant light, the vibrant colors, the bustling street life, the distinct architecture, and the unfamiliar customs of the region. Like many Western artists before him, including the Romantic pioneer Eugène Delacroix, whose sketches from Morocco in the 1830s had a profound impact, Bridgman found a wealth of new and exciting subject matter.

Bridgman was not a mere tourist; he immersed himself in the local cultures, sketching prolifically and collecting artifacts, textiles, and costumes. These items would later populate his Paris studio, allowing him to recreate scenes with a degree of authenticity. He made subsequent trips to Algeria and Egypt throughout the 1870s and 1880s, deepening his understanding and expanding his repertoire of subjects. His travels were not always easy, but his dedication to firsthand observation set his work apart. He was particularly drawn to Algeria, and his book, Winters in Algeria, published in 1890, provided a written account of his experiences, further showcasing his engagement with the region.

Defining Bridgman's Orientalism

Orientalism, as an artistic and cultural phenomenon, involved the depiction of North African, Middle Eastern, and Asian cultures by Western artists, writers, and scholars. It often reflected Western perceptions, fantasies, and sometimes colonial attitudes towards these regions. Bridgman's Orientalism, while fitting within this broader movement, had its own distinct characteristics. He was less inclined towards the overtly sensual or violent themes found in the work of some of his contemporaries. Instead, he often focused on scenes of daily life, domestic interiors, street markets, and architectural studies.

His paintings, such as "A Street Scene in Algiers" or "An Interesting Game" (also known as "The Diversion of an Assyrian King," though its setting is more broadly ancient Near Eastern), showcase his ability to combine detailed observation with a sense of atmosphere. He was particularly adept at rendering the effects of sunlight, creating a luminous quality in his canvases. While Gérôme's influence remained, Bridgman developed a brighter palette and a somewhat looser brushstroke in his later works, distinguishing his style. He shared with artists like Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst, both Austrian Orientalists working in Paris, a fascination with ethnographic detail and the material culture of the regions they depicted. However, Bridgman's American perspective and his more frequent, direct engagement with North Africa perhaps lent a different nuance to his work compared to some European counterparts like the British painter John Frederick Lewis, known for his incredibly detailed watercolors of Cairo.

Masterworks and Signature Themes

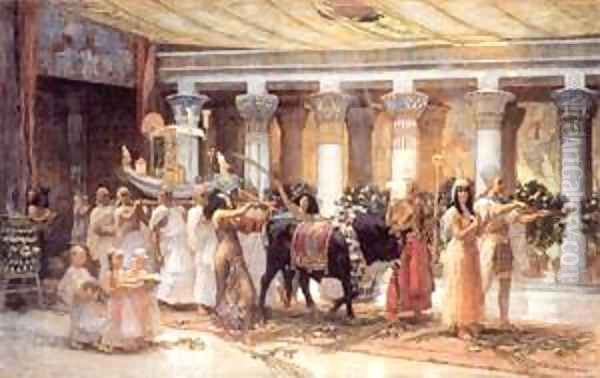

One of Bridgman's most celebrated early works is "The Funeral of a Mummy" (1876-77, Speed Art Museum). Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1877 and later at the Exposition Universelle of 1878, this grand historical painting depicts a funerary procession on the Nile River in ancient Egypt. Its archaeological accuracy, dramatic composition, and evocative mood garnered widespread acclaim, earning Bridgman the Cross of the Legion of Honor and cementing his reputation. The painting demonstrated his ability to synthesize historical research with artistic imagination, a skill highly valued in academic circles.

Beyond such historical reconstructions, Bridgman excelled in capturing the contemporary life of North Africa. Works like "The Siesta" (circa 1878) or "In a Village, El Biar, Algeria" (1880) offer glimpses into quiet domestic moments or bustling outdoor scenes. He often depicted women in interior settings, though generally with more decorum and less overt exoticism than some of his peers. His handling of light, particularly the way it filtered through latticework or illuminated courtyards, became a signature element. He also painted numerous portraits of local people, capturing their dignity and individuality. His ability to convey texture – the shimmer of silk, the roughness of stone, the softness of skin – was remarkable. These works resonated with a Western audience eager for images of distant and seemingly timeless lands.

Recognition and Success

Bridgman achieved considerable success during his lifetime. He was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the premier art exhibition in the world, and his works were often well-received by critics and the public. His paintings commanded high prices, and he attracted wealthy patrons on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, he was hailed as one of the nation's foremost artists. He held major solo exhibitions, notably one at the American Art Galleries in New York in 1881, which featured over 300 of his works and was a resounding success. Another significant exhibition followed in 1890.

His achievements were recognized with numerous awards and honors. Besides the Legion of Honor, he received medals at various international expositions. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Design in New York and maintained connections with the American art world even while based primarily in Paris. He was sometimes referred to as the "American Gérôme," a testament to his skill and the lineage of his training, though he developed his own distinct artistic voice. He was a contemporary of other successful American artists working in Paris, such as John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt, though his subject matter and style differed significantly from theirs. He also shared the Orientalist field with fellow American Edwin Lord Weeks, who also traveled extensively and painted scenes of India and Persia.

Later Career and Evolving Styles

As the 19th century drew to a close and the 20th century began, artistic tastes began to shift dramatically. The rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism challenged the dominance of academic art. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso were forging new visual languages that prioritized subjective experience, formal innovation, and a break from traditional representation. While Bridgman continued to paint and exhibit, the academic style he represented gradually fell out of favor with the avant-garde and, eventually, with broader public taste.

In his later career, Bridgman did experiment with other themes and styles. He painted portraits of society figures, as well as historical and biblical subjects, and even some Symbolist-inflected works. However, these later efforts did not achieve the same level of acclaim or popular success as his Orientalist paintings. His commitment to meticulous realism and narrative clarity, once seen as strengths, were increasingly viewed as old-fashioned by a new generation of artists and critics. Despite this shift in artistic fashion, he remained a respected figure, continuing to work from his studio in Paris and later in Lyons-la-Forêt in Normandy.

Beyond the Canvas: Other Pursuits

Bridgman was a man of diverse talents. In addition to his prolific output as a painter, he was also a writer and a musician. His book, Winters in Algeria (1890), illustrated with his own drawings, offered personal and descriptive accounts of his travels and observations in Algeria, providing valuable insights into his experiences and the region as he saw it. This publication further solidified his reputation as an authority on North African subjects.

He also composed music, including orchestral pieces and songs. This multifaceted creativity suggests an intellectually curious and artistically versatile individual. While his paintings remain his primary legacy, these other pursuits offer a fuller picture of the man and his engagement with the world. His ability to articulate his experiences in writing and music complements the visual narratives he created on canvas, showcasing a deep and sustained engagement with his chosen subjects.

Legacy and Reassessment

Frederick Arthur Bridgman passed away in Rouen, France, on January 13, 1928. By the time of his death, his style of painting was largely eclipsed by Modernist movements. For much of the 20th century, academic art, and Orientalism in particular, was often dismissed or overlooked by art historians focused on the narrative of Modernism. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant reassessment of 19th-century academic art. Scholars and curators have begun to re-examine figures like Bridgman, appreciating their technical skill, their cultural significance, and the complex ways in which they engaged with their subject matter.

Today, Bridgman's paintings are held in major museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Louvre in Paris. Exhibitions of Orientalist art have brought his work to new audiences, prompting fresh interpretations. While contemporary viewers may approach his depictions of North Africa with a critical awareness of the colonial context and the potential for exoticizing stereotypes inherent in Orientalism (as famously critiqued by Edward Said), Bridgman's best work transcends simple categorization. His paintings offer a visually rich and often empathetic portrayal of the cultures he encountered, filtered through the lens of a highly skilled 19th-century American artist. His dedication to capturing the light, color, and life of the "Orient" left an indelible mark on the art of his time. His contemporaries in the Orientalist genre, such as the French painters Eugène Fromentin and Gustave Guillaumet, also contributed significantly to this visual record, each with their unique perspectives.

Conclusion

Frederick Arthur Bridgman was a pivotal figure in American art and a leading exponent of the Orientalist genre. From his early training as an engraver in New York to his tutelage under Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris, he developed an exceptional technical mastery. His extensive travels in North Africa provided him with a rich tapestry of subjects, which he translated into luminous, detailed, and evocative paintings that captivated audiences in Europe and America. Works like "The Funeral of a Mummy" and his numerous scenes of Algerian life established him as a major artist, earning him accolades and commercial success.

While the tides of artistic taste shifted away from academic realism during his later career and for much of the 20th century, Bridgman's contributions are now being recognized anew. He stands as a testament to the global ambitions of American artists in the 19th century and as a key figure in the complex and fascinating tradition of Orientalist painting. His legacy endures in his vibrant canvases, which continue to transport viewers to the sunlit streets, bustling markets, and quiet interiors of a world that fascinated him and, through his art, continues to fascinate us. His work, alongside that of artists like Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant or Mariano Fortuny, enriches our understanding of the diverse artistic currents of the 19th century.