Prosper Georges Antoine Marilhat stands as a significant, if somewhat tragically short-lived, figure in the vibrant tapestry of 19th-century French art. A prominent member of the Orientalist school, his canvases transported Parisian audiences to the sun-drenched landscapes and bustling cityscapes of Egypt and the Near East. His meticulous attention to detail, combined with a Romantic sensibility for atmosphere and light, carved a unique niche for him among his contemporaries. This exploration delves into his life, his transformative travels, his artistic style, his key works, his connections within the art world, and his enduring, albeit curtailed, legacy.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations in Auvergne

Born on March 26, 1811, in Vertaizon, a small commune in the Puy-de-Dôme department in Auvergne, central France, Prosper Marilhat hailed from a family with a background in banking. This provincial upbringing, far from the artistic hub of Paris, might have initially suggested a different path. His early education took place at the Château de Sauvagnat, also in the Auvergne region, a setting that perhaps instilled in him an appreciation for landscape and architecture.

His initial foray into a professional career was not in the arts but in the practical trade of clockmaking. He began this pursuit locally and later moved to Thiers, a town renowned for its cutlery and, by extension, its skilled metalworkers and artisans, including those in horology. This early training in a craft demanding precision and attention to detail may have subtly influenced his later artistic practice, particularly his meticulous rendering of architectural elements and intricate patterns. However, the allure of painting eventually proved stronger than the mechanics of timepieces. The artistic currents of the era, particularly the burgeoning Romantic movement with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and often exotic subject matter, were beginning to permeate even provincial France, likely capturing the young Marilhat's imagination.

The Parisian Nexus and Formative Artistic Development

Recognizing that his artistic ambitions required a more stimulating environment and formal training, Marilhat made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. The French capital was, then as now, the epicenter of the European art world, home to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, influential private ateliers, and the all-important annual Salon, the official art exhibition sponsored by the French government.

In Paris, Marilhat sought to refine his skills. While the provided information doesn't specify a single, long-term master, it's highly probable he frequented various studios and absorbed the prevailing artistic theories. Some accounts suggest an association with or admiration for the circle of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, a prominent Napoleonic-era painter whose work bridged Neoclassicism and emerging Romanticism. More significantly, he is often linked, at least in terms of stylistic affinity and a shared dedication to precise draughtsmanship, with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, the towering figure of French Neoclassicism. While direct, prolonged tutelage under Ingres isn't definitively documented for Marilhat in the same way it was for artists like Théodore Chassériau, the emphasis on line, clarity, and careful composition evident in some of Marilhat's work suggests an awareness and respect for Ingres's principles, even if his ultimate path led him towards the more evocative and colorful realm of Orientalism.

The Paris of the 1820s and early 1830s was a ferment of artistic ideas. Eugène Delacroix, the standard-bearer of French Romanticism, was already making waves with his dramatic and richly colored canvases. The interest in faraway lands, fueled by colonial expansion, scientific exploration, and literary works, was growing, laying the groundwork for the Orientalist movement that would so define Marilhat's career.

The Transformative Journey to the East

The most decisive period in Marilhat's artistic development and the one that cemented his reputation was his journey to the Near East. In 1831, at the age of twenty, he seized the opportunity to join a scientific expedition led by Baron von Hügel, a German naturalist and explorer. This expedition was not merely a leisurely tour but a serious undertaking aimed at scientific and cultural discovery. Over the next two years, from 1831 to 1833, Marilhat traveled extensively through regions that were then considered exotic and largely unknown to the general European public: Greece, Syria, Palestine, and, most importantly for his art, Egypt.

He spent a significant portion of this period, reportedly up to two years, in Egypt, with an extended stay in Cairo. This immersion was crucial. Unlike artists who made brief visits, Marilhat had the time to absorb the atmosphere, study the architecture, observe the daily life of the people, and meticulously document his surroundings. He filled numerous sketchbooks with drawings and watercolors, capturing the quality of light, the textures of ancient stones, the vibrant colors of local attire, and the unique forms of Islamic architecture. These on-the-spot studies would become an invaluable resource, providing authentic material for his oil paintings upon his return to Paris. This direct, prolonged engagement with his subject matter distinguished his work from some Orientalists who relied more heavily on secondary sources or fleeting impressions. His companion during part of these travels, or at least someone he invited to join him in the Near East, was the artist Charles-Théodore-Frédéric-Louis-Joseph-Eustache de Saulcy, often known simply as Charles Eustache, further highlighting the collaborative and adventurous spirit of artists during this period.

The Essence of Marilhat's Orientalism

Upon his return to Paris around 1833, Marilhat began to translate his travel sketches and experiences into finished oil paintings. He quickly established himself as a leading figure among the second wave of Orientalist painters, a movement that had been gaining momentum since Napoleon's Egyptian campaign at the turn of the century and was further popularized by writers like Victor Hugo and artists like Delacroix, who had himself traveled to North Africa in 1832.

Marilhat's Orientalism, however, often possessed a distinct character. While Delacroix might focus on the drama, dynamism, and sensuality of the Orient, and later artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme would become known for their highly polished, almost photographic realism and sometimes ethnographic detail, Marilhat's vision was often more serene, focused on the interplay of light and shadow on architecture and the poetic atmosphere of landscapes. His works frequently depicted tranquil street scenes, majestic mosques, ancient ruins, and expansive views along the Nile. He was less concerned with grand historical narratives or overtly dramatic human interactions, and more with capturing the timeless beauty and unique character of the places he had visited. His paintings often evoke a sense of calm and contemplation, inviting the viewer to step into these meticulously rendered, sunlit worlds. He shared this fascination with the East with contemporaries like Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, who was also known for his scenes of Middle Eastern life, and Horace Vernet, who painted numerous scenes from the French campaigns in North Africa but also more general Orientalist subjects.

Artistic Style and Technique: Light, Detail, and Romantic Atmosphere

Marilhat's style was a sophisticated blend of careful observation, academic discipline, and Romantic sensibility. His early training, possibly influenced by Neoclassical ideals of clarity and precision, is evident in his accurate drawing and his ability to render complex architectural forms with conviction. However, this precision was always in service of a larger atmospheric effect.

Light was a central element in his work. He was a master at capturing the brilliant, often harsh, sunlight of Egypt, the cool transparency of shadows, and the subtle gradations of tone in the sky at dawn or dusk. His canvases often possess a remarkable luminosity, making the stone of ancient temples or the whitewashed walls of Cairene houses seem to radiate warmth. This sensitivity to light was a hallmark of the best Orientalist painters, who sought to convey the unique visual environment of the regions they depicted.

His brushwork could vary from smooth, almost invisible strokes in passages requiring fine detail, to more visible, textured applications of paint, particularly in rendering foliage or rough-hewn stone. His palette was rich and nuanced, capable of capturing both the vibrant hues of local dress and the more subtle earth tones of the desert and ancient structures. While his compositions were carefully constructed, often with a strong sense of perspective and spatial depth, they rarely felt rigid or overly academic. Instead, they were imbued with a poetic quality, a Romantic feeling for the picturesque and the sublime, that resonated with the tastes of his time. He shared this Romantic leaning with landscape painters in France like Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau of the Barbizon School, though their subject matter was primarily French scenery.

Masterpieces and Key Works: Visions of Egypt and Beyond

Marilhat produced a significant body of work during his relatively short career. Several paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

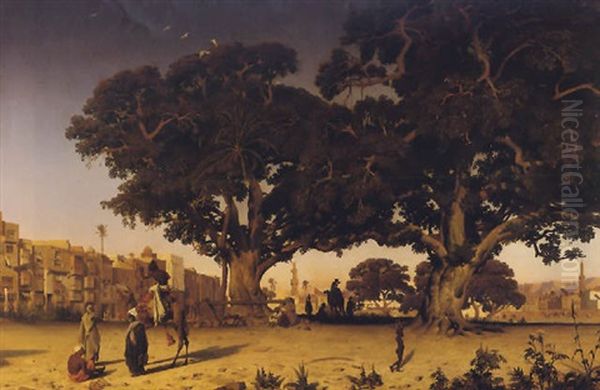

<em>Place de l'Esbekieh au Caire</em> (The Esbekieh Square in Cairo): Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1834, this was one of his early successes. The Esbekieh was a central public space in Cairo, and Marilhat depicted it with a keen eye for architectural detail and the lively, yet unchaotic, presence of figures. This work helped to establish his reputation as an authentic portrayer of Egyptian life.

<em>Une rue au Caire</em> (A Street in Cairo) / <em>Vieille Rue du Caire</em> (Old Cairo Street): Variations on this theme appear in his oeuvre. These paintings typically showcase narrow, winding streets, overhanging wooden balconies (mashrabiyas), and the interplay of bright sunlight and deep shadow, often populated by figures in local attire going about their daily business. One notable version, often simply titled Old Cairo, depicts a covered market scene with distant palm trees and a mosque bathed in dramatic light, showcasing his skill in creating depth and atmosphere. This work is held in high esteem and often cited.

<em>Paysage avec mosquée</em> (Landscape with Mosque): Several works bear similar titles, indicating his fascination with Islamic architecture within its natural setting. One such painting, now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., is a fine example of his ability to integrate monumental structures into a harmonious landscape, emphasizing the serene beauty of the scene.

<em>Mosquée à la Basse-Egypte</em> (Mosque in Lower Egypt): This title also points to his focus on specific architectural studies, likely capturing the distinct characteristics of mosques found in the Nile Delta region.

<em>Souvenir de la campagne de Rosette</em> (Memory of the Rosetta Countryside): This work, exhibited at the Salon of 1844, highlights his ability to evoke the particular atmosphere of the Egyptian landscape, likely featuring the Nile, palm groves, and perhaps distant villages.

<em>L'Erechthéion, Athènes</em> (The Erechtheum, Athens): While Egypt was his primary focus, his travels also took him to Greece. This painting demonstrates his skill in rendering classical ruins with the same sensitivity to light and texture that he applied to Egyptian subjects.

<em>Arabes Syriens en voyage</em> (Syrian Arabs Traveling): This painting, also shown at the 1844 Salon, indicates his interest in depicting the people and customs of the broader Near East, not just Egypt.

His works were regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon, the premier venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. The Salon of 1844 was a particular triumph for Marilhat; he exhibited eight paintings and was awarded a first-class gold medal, a significant honor that solidified his standing in the Parisian art world.

Contemporaries, Collaborators, and Students

Marilhat operated within a dynamic artistic community. His most obvious connections were with fellow Orientalists. He was a contemporary of Eugène Delacroix, whose own journey to Morocco and Algeria in 1832 had a profound impact on his art and on the Orientalist movement as a whole. While Delacroix's style was generally more dramatic and painterly, both artists shared a passion for the light and color of North Africa and the Near East. Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps was another key Orientalist active at the same time, known for his genre scenes and landscapes of the Ottoman Empire. Horace Vernet was also a prominent figure, though his Orientalism was often tied to French military exploits.

Marilhat also had connections with artists beyond the Orientalist circle. As mentioned, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres represented an important, if contrasting, pole in French art, emphasizing line and classical form. Marilhat's ability to combine detailed rendering with atmospheric effect suggests he navigated between these influences.

In terms of direct mentorship, Marilhat himself became a teacher. Théodore Chassériau, a brilliant artist who successfully fused the linear grace of his master Ingres with the Romantic colorism of Delacroix, and who also became a notable Orientalist, painted a portrait of Marilhat around 1831-1832, when Chassériau was still a teenager. This suggests Marilhat played an early mentoring role for the young Chassériau. Another artist sometimes mentioned as his student is Gaspard Lacroix (Charles-François-Gaspard de la Croix), who also painted landscapes and Orientalist scenes. The claim that Henri Duvieux was a student is chronologically problematic, as Duvieux (born 1855) would have been a child when Marilhat died, making direct tutelage impossible; perhaps Duvieux was an admirer or influenced by Marilhat's posthumous reputation.

He also collaborated or traveled with other artists, such as Charles Eustache, whom he reportedly invited to join him in the Near East. The art world of Paris was relatively small, and artists often interacted at Salons, in studios, and in social circles. Figures like Jean-François Millet, known for his peasant scenes and a key member of the Barbizon School, or Paul Delaroche, a highly successful historical painter, would have been prominent contemporaries whose careers overlapped with Marilhat's, even if their artistic concerns differed. The landscape painter Camille Corot and the Barbizon leader Théodore Rousseau were also active, shaping French landscape painting in ways that paralleled, yet diverged from, Marilhat's Orientalist landscapes.

The Tragic Decline and Premature End

Despite his successes, including the gold medal at the 1844 Salon, Marilhat's later years were marked by profound disappointment and tragedy. A significant source of his distress was reportedly his failure to receive the Cross of the Legion of Honour, a prestigious state award that conferred considerable status. For an artist who had achieved critical acclaim and popular recognition, this perceived slight may have been deeply wounding.

This disappointment, possibly compounded by other personal or professional pressures, appears to have contributed to a decline in his mental health. Sources indicate that he suffered from periods of mental instability or "insanity." His promising career was cut tragically short when he died on September 13, 1847, in Thiers, the town of his earlier clockmaking endeavors. He was only 36 years old. Some accounts suggest his death was by suicide, a desperate end for an artist who had brought so much beauty and light to his canvases.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Prosper Marilhat's early death undoubtedly curtailed what could have been an even more significant contribution to French art. Nevertheless, in his relatively brief career, he created a body of work that remains highly regarded for its sensitivity, authenticity, and artistic skill. He is considered one of the most accomplished of the French Orientalist painters, particularly admired for his luminous depictions of Egypt.

His paintings offered a vision of the East that was both meticulously observed and poetically rendered, satisfying the 19th-century European appetite for exoticism while also achieving a high degree of artistic merit. His work influenced subsequent generations of Orientalist painters, and his canvases continue to be prized by collectors and museums. Major institutions such as the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Musée d'Orsay (which houses 19th-century art), the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, the Wallace Collection in London, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., hold examples of his work, attesting to his enduring importance.

Marilhat's legacy lies in his ability to transport viewers to another time and place, not through grand historical narratives, but through the quiet beauty of a sunlit ruin, the intricate detail of a bustling street, or the serene expanse of a desert landscape. He captured a specific vision of the Orient, filtered through a Romantic sensibility yet grounded in careful observation, leaving behind a luminous record of his travels and his artistic talent. His premature death was a loss to the art world, but the works he left behind continue to enchant and inform.

Conclusion: A Singular Visionary of the Sunlit East

Prosper Georges Antoine Marilhat, in his brief but impactful career, carved out a distinctive place in the annals of 19th-century French art. From his beginnings in Auvergne and his early training in a meticulous craft, he rose to become a celebrated Orientalist painter in Paris. His transformative journey to Egypt and the Near East provided the inspiration for a body of work characterized by its luminous depiction of light, its careful attention to architectural and natural detail, and its pervasive Romantic atmosphere. His paintings of Cairo's streets, Nile landscapes, and ancient monuments offered French audiences an authentic yet poetic glimpse into worlds then considered distant and mysterious. Despite the tragic circumstances of his early death, Marilhat's artistic achievements, recognized by Salon honors and the admiration of his peers like Chassériau, ensure his legacy as a significant contributor to the Orientalist movement and a master of capturing the unique essence of the lands he so meticulously portrayed. His works remain a testament to a singular artistic vision that continues to resonate with viewers today.