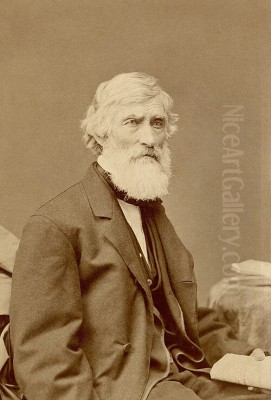

Asher Brown Durand stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of American art. Born during the nascent years of the United States and living through its tumultuous adolescence into maturity, Durand (1796-1886) not only witnessed profound national transformation but actively shaped its artistic identity. Primarily celebrated as a leading voice of the Hudson River School, America's first distinct school of landscape painting, Durand's journey began not with a brush, but with the engraver's burin. His meticulous skill in engraving laid the foundation for a career that would eventually champion a deeply felt, realistic portrayal of the American wilderness, leaving an indelible mark on how the nation perceived its own natural heritage. His influence extended beyond his canvases, permeating art theory, education, and the very institutions that would nurture future generations of American artists.

From Engraver's Apprentice to Master Craftsman

Asher B. Durand's story begins in Jefferson Village (now Maplewood), New Jersey, in 1796. His initial artistic inclinations were channeled into the practical craft of engraving, a skill likely fostered in his father's watchmaking and silversmithing shop. Formal training commenced in 1812 when he became an apprentice to the Newark engraver Peter Maverick. Durand proved an adept student, quickly mastering the demanding techniques of the medium.

By 1817, the apprenticeship had evolved into a partnership. The firm of Maverick & Durand gained recognition, but Asher Durand's individual reputation soared following his masterful engraving of John Trumbull's iconic painting, Declaration of Independence, completed in 1823. This intricate work, requiring immense patience and precision, established Durand as one of the foremost engravers in the country. His skill was sought after for banknote engraving, book illustrations, and reproductions of other artworks, providing him with financial stability and a respected position in the artistic community of New York City. This period honed his eye for detail and composition, skills that would prove invaluable in his later career.

The Call of the Canvas: Embracing Landscape Painting

Despite his success as an engraver, Durand felt the pull of painting. Around the 1830s, encouraged by the influential New York merchant and art patron Luman Reed, Durand began to dedicate more time to oil painting, initially focusing on portraiture, genre scenes, and depictions of historical or literary themes, aligning with the prevailing tastes of the era. Reed's patronage was crucial, providing not just commissions but also intellectual stimulus and connections within the burgeoning New York art world.

A significant turning point came through his burgeoning friendship with Thomas Cole, often considered the founder of the Hudson River School. Cole's dramatic and often allegorical landscapes deeply impressed Durand. In 1837, the two artists embarked on a sketching expedition to Schroon Lake in the Adirondack Mountains. This trip was transformative for Durand. Immersed in the wilderness alongside Cole, he fully embraced landscape painting as his primary focus, captivated by the direct encounter with nature's forms, textures, and light. This experience solidified his commitment to capturing the specific character of the American landscape.

The Hudson River School and the Philosophy of Naturalism

Durand quickly became a central figure in the Hudson River School, a movement characterized by a shared belief in the aesthetic and spiritual significance of the American landscape. While Cole often imbued his scenes with allegory and historical narrative, Durand championed a more direct, naturalistic approach. He believed that the artist's highest calling was to represent nature as faithfully as possible, seeing divinity revealed in the intricate details of the natural world.

This philosophy was articulated in his influential "Letters on Landscape Painting," published in the art journal The Crayon in 1855. In these essays, Durand advised aspiring artists to study nature directly, advocating for meticulous plein air (outdoor) sketching as the foundation for larger studio compositions. He urged painters to render trees, rocks, and foliage with botanical and geological accuracy, believing that "the true province of Landscape Art is the representation of the work of God in the visible creation." This emphasis on empirical observation and detailed realism became a hallmark of his style and distinguished his work within the broader movement. His approach resonated with the era's burgeoning scientific interest and a nationalistic pride in the unique features of the American continent.

Masterworks: Capturing the American Scene

Durand's commitment to naturalism yielded a body of work celebrated for its detail, serenity, and profound connection to place. Among his most famous paintings is Kindred Spirits (1849), a poignant tribute painted the year after Thomas Cole's untimely death. Commissioned by the patron Jonathan Sturges as a gift for the poet William Cullen Bryant, the painting depicts Cole and Bryant standing on a rocky ledge overlooking a gorge in the Catskill Mountains. It is a masterful composition, embodying the Romantic ideal of communion between humanity, nature, and the arts, celebrating the shared reverence for the American wilderness held by the painter and the poet. The meticulous rendering of the foliage, rocks, and atmospheric perspective exemplifies Durand's mature style.

Another significant work, Progress (The Advance of Civilization) (1853), offers a more complex commentary. While celebrating the beauty of the landscape in the foreground, the painting depicts the encroachment of settlement – cleared forests, railroads, telegraph wires, and burgeoning towns – into the wilderness. It reflects the era's ambivalent relationship with westward expansion and industrialization, acknowledging technological advancement while perhaps subtly mourning the loss of pristine nature. This work showcases Durand's ability to infuse landscape with narrative and social reflection.

Other notable paintings further illustrate his dedication to specific natural effects and locations. Summer Afternoon (c. 1865) captures the hazy, languid light of a warm day, while In the Woods (1855) offers an intimate, immersive view of a forest interior, focusing on the textures of bark, leaves, and dappled sunlight. Works like The Catskills and The Beeches demonstrate his deep familiarity with and affection for the landscapes of the Hudson Valley and surrounding regions. His painting Thanatopsis (c. 1850), likely inspired by Bryant's poem of the same name, uses landscape elements – a funeral procession, ancient trees, a setting sun – to meditate on themes of life, death, and nature's cyclical continuity, revealing the potential for spiritual depth within his naturalistic framework.

A Network of Artists and Patrons

Durand's career unfolded within a vibrant artistic community. His relationship with Thomas Cole was foundational, evolving from mentorship and influence to deep friendship and mutual respect. He was also close to Cole's wife, Maria Bartow Cole (often referred to as Anne Cole in some sources, though Maria is generally accepted), who shared his artistic milieu. The poet William Cullen Bryant, depicted in Kindred Spirits, was another key figure in this circle, his nature poetry resonating strongly with the Hudson River School ethos.

Beyond Cole and Bryant, Durand interacted with a wide array of contemporaries. His early engraving work connected him with figures like John Trumbull. His friendship with the sculptor Henry Kirke Brown led to shared travels and artistic discussions. He maintained connections with portraitists like Samuel Waldo, for whom he engraved the print Old Pat (A Beggar with a Bone) based on Waldo's painting.

As a leading figure in the Hudson River School, Durand was associated with the next generation of landscape painters who followed his naturalistic principles, including John Frederick Kensett, Sanford Robinson Gifford, and Jasper Francis Cropsey. While perhaps less overtly dramatic than Albert Bierstadt or Frederic Edwin Church, who explored grander, more exotic landscapes, Durand's focus on the intimate beauty of the northeastern wilderness provided a crucial counterpoint and foundational practice for the school. The role of patrons like Luman Reed and Jonathan Sturges was indispensable, providing financial support and intellectual encouragement that enabled Durand and his contemporaries to pursue their artistic visions.

Building Institutions: Educator and Leader

Durand's commitment to American art extended far beyond his own easel. He was deeply involved in establishing the institutional framework necessary for the arts to flourish in the young nation. In 1825, frustrated with the conservative policies of the existing American Academy of the Fine Arts (led by John Trumbull), Durand, along with Samuel F.B. Morse, Thomas Cole, and others, founded the New-York Drawing Association. This group emphasized instruction based on drawing from life and antique casts.

This association quickly evolved into the National Academy of Design (NAD) in 1826, an artist-run organization dedicated to exhibition and education. Durand was a charter member and remained deeply involved throughout his life. He served as the Academy's president for a significant period, from 1845 to 1861, guiding the institution through crucial years of growth. His leadership fostered a supportive environment for artists and promoted high standards of training, directly influencing generations of American painters. He was also active in other artistic circles, including the Sketch Club and the Century Association (initially the Lunch Club), forums for artists and intellectuals to exchange ideas. His "Letters on Landscape Painting" further cemented his role as a leading theorist and educator.

Later Life, Recognition, and Market Legacy

Durand continued to paint actively into the 1870s, though his later work sometimes reflected a slightly looser, more atmospheric style, perhaps influenced by Barbizon painting. He spent his final years primarily at his family home in Maplewood, New Jersey, passing away in 1886 at the age of 90. While respected during his lifetime, particularly within the art community, the broader public appreciation for the Hudson River School waned towards the end of the 19th century with the rise of newer styles like Impressionism.

However, the 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in Durand and his contemporaries. Art historians recognized the crucial role the Hudson River School played in developing a distinctly American artistic voice. Today, Durand is hailed as a foundational figure, the "Dean of American Landscape Painting." His works are held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Princeton University Art Museum, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

The high regard for Durand's work is reflected in the auction market. His masterpiece, Kindred Spirits, achieved a landmark price of $35 million at a Sotheby's auction in 2005, purchased for the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. This set a record at the time for a work by an American painter. Progress also commanded a significant sum, reportedly acquired privately for around $40-50 million before being donated to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in 2019. While not all his works reach such astronomical figures – paintings like Lake Hamlet (Passing Shower) have sold for substantial but lower amounts (e.g., $491,400 in one instance) – his major canvases remain highly sought after by collectors and institutions, confirming their enduring artistic and historical significance.

Enduring Influence: The Legacy of Asher B. Durand

Asher Brown Durand's legacy is multifaceted. As an engraver, he achieved the pinnacle of technical mastery, contributing significantly to the visual culture of his time. As a painter, he was instrumental in shifting the focus of American art towards the national landscape, championing a naturalistic approach grounded in direct observation and meticulous detail. His work captured not just the topography of the American Northeast but also the spirit of reverence and quiet contemplation that the wilderness inspired in the 19th-century imagination.

Through his "Letters on Landscape Painting" and his long tenure leading the National Academy of Design, he profoundly shaped artistic theory and education in the United States. He mentored and influenced countless artists, embedding the practice of plein air sketching and detailed realism into the core of American landscape tradition. While Thomas Cole may have provided the initial spark for the Hudson River School with his dramatic visions, Durand provided its philosophical anchor in naturalism and its practical methodology. His life and work embody the transition of American art from its European-derived roots to a confident expression of national identity, forever linking the American spirit to the beauty and specificity of its own land.