Introduction: A New Focus for American Art

Thomas Doughty, born in Philadelphia in 1793 and passing away in New York City in 1856, holds a unique and foundational place in the annals of American art history. He was, by most accounts, the very first American-born artist to dedicate his career exclusively to the genre of landscape painting. At a time when portraiture dominated the American art market, Doughty's commitment to depicting the natural scenery of his homeland was a pioneering act. His quiet, lyrical, and often atmospheric paintings of the rivers, mountains, and forests of the northeastern United States helped lay the groundwork for the nation's first major art movement, the Hudson River School. His work signaled a growing appreciation for the American wilderness and a burgeoning desire to capture its distinct beauty.

Doughty's path to becoming a professional artist was not straightforward. He initially entered the business world, working in the leather industry. However, a passion for art, particularly the beauty of the natural world, led him to make a significant career change around 1820. Largely self-taught, though likely benefiting from studying European prints and perhaps receiving some informal instruction, Doughty quickly developed a recognizable style. His dedication earned him recognition early on, notably his election as an honorary member of the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York in 1827, a testament to his emerging stature in the American art community.

From Leather Merchant to Landscape Painter

Born into a burgeoning nation finding its cultural footing, Thomas Doughty's early life in Philadelphia placed him in one of America's most vibrant urban centers. Yet, his artistic inclinations drew him away from the demands of commerce. The decision to abandon his established career in the leather trade around the age of 27 was a bold one. In the early 19th century, landscape painting was not considered a particularly lucrative or prestigious field in the United States, lagging far behind portraiture in patronage and critical esteem. Artists typically relied on portraits, historical scenes, or didactic subjects for their income.

Doughty's commitment, therefore, was not just a personal choice but a statement about the potential validity and importance of landscape as a subject worthy of serious artistic pursuit in America. His early works quickly gained notice for their charm and sensitivity. He focused on the scenery readily available to him, particularly the picturesque river valleys and rolling hills of his native Pennsylvania. His approach was less about topographical accuracy in the strictest sense and more about capturing the mood and atmosphere of a place, often imbuing his scenes with a sense of tranquility and poetic sentiment that resonated with the Romantic sensibilities of the era.

His self-directed education likely involved close study of engravings and paintings by European landscape masters. Influences from artists like the 17th-century French painter Claude Lorrain, known for his idealized landscapes and masterful handling of light, can often be discerned in Doughty's compositional structures and atmospheric effects. However, Doughty adapted these European conventions to distinctly American settings, finding beauty not in classical ruins but in the unspoiled woods and waterways of the New World. This adaptation was crucial in forging a path for a uniquely American school of landscape painting.

The Dawn of American Landscape Painting

Thomas Doughty emerged as an artist during a period of intense national growth and self-discovery in the United States. Following the War of 1812, there was a rising tide of nationalism and a growing interest in defining what made America unique. The vast, relatively untouched wilderness of the continent became a powerful symbol of this national identity – a source of pride, inspiration, and even spiritual solace. Writers like James Fenimore Cooper were celebrating the American frontier in literature, and artists like Doughty began to do the same on canvas.

His decision to specialize in landscape coincided with, and arguably helped to foster, this cultural shift. Before Doughty, landscape often appeared merely as a backdrop for portraits or historical events. Artists like Washington Allston, an earlier American Romantic painter, certainly incorporated landscape elements, but Doughty was among the very first to make the landscape itself the primary subject. He demonstrated that American scenery possessed a beauty and grandeur worthy of artistic representation in its own right.

His early success encouraged others. He was a contemporary of painters like Alvan Fisher, another early American landscapist based in Boston, and Thomas Birch, a Philadelphia-based marine painter who also depicted coastal landscapes. Together, these artists began to cultivate an American audience for landscape art. Doughty's particular contribution was his consistent focus and his development of a lyrical, accessible style that appealed to patrons seeking pleasing, non-controversial views of nature. His work offered an escape into serene, idealized versions of the American countryside.

Artistic Style: Lyrical Views of Nature

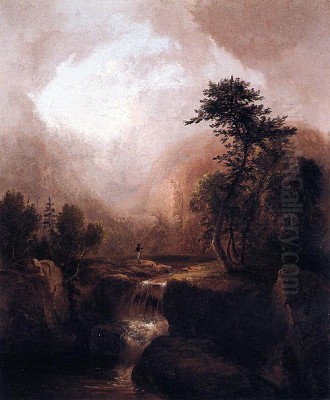

Thomas Doughty's artistic style is characterized by its quiet lyricism, delicate rendering, and emphasis on atmospheric effects. His paintings rarely depict dramatic storms or sublime, overwhelming vistas in the manner of some later Hudson River School artists. Instead, he favored tranquil scenes: calm rivers reflecting autumnal foliage, hazy mountains receding into the distance, peaceful woodlands bathed in soft light. His compositions are typically well-balanced and harmonious, often employing established landscape conventions like framing trees and a clear progression from foreground to background.

His brushwork is generally controlled and detailed, particularly in his earlier works, allowing for a clear depiction of foliage, rocks, and water. However, this detail is often softened by a subtle haze or atmospheric perspective that lends his scenes a gentle, slightly dreamlike quality. He was particularly adept at capturing the nuances of light and air, often favoring the soft illumination of early morning or late afternoon. This focus on atmosphere contributes significantly to the tranquil, sometimes melancholic, mood that pervades much of his work.

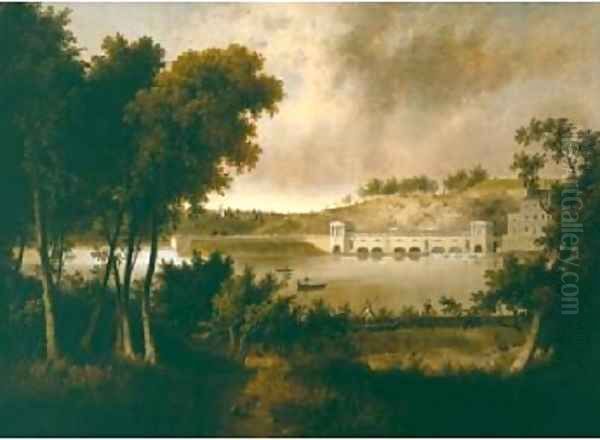

While influenced by European traditions, Doughty's landscapes possess a distinctly American feel. His subjects were the specific locales he knew and visited: the banks of the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers in Pennsylvania, the Hudson River Valley and the Catskill Mountains in New York, and the scenic areas of New England. He rendered these familiar scenes with an intimacy and affection that distinguished them from the more generalized or classically inspired landscapes of European convention. His work invited viewers to appreciate the specific beauties of their own land.

A Pioneer of the Hudson River School

Thomas Doughty is rightly considered one of the founding figures of the Hudson River School, America's first coherent school of landscape painting. While Thomas Cole is often credited as the movement's principal founder due to his more dramatic and allegorical works that captured public attention in the mid-1820s, Doughty's dedication to landscape predates Cole's rise and helped pave the way. Doughty's focus on the specific scenery of the Hudson River Valley and surrounding regions, rendered with a combination of realistic detail and Romantic sensibility, established key tenets of the school.

The Hudson River School artists shared a belief in the spiritual and moral significance of nature. They saw the American wilderness not just as beautiful scenery but as a manifestation of God's creation and a source of national virtue. Doughty's serene and harmonious landscapes, while perhaps less overtly didactic than Cole's, participated in this broader cultural project. They presented nature as a place of peace, refuge, and quiet contemplation, implicitly contrasting it with the growing urbanization and industrialization of American society.

Doughty worked alongside and influenced the first generation of Hudson River School painters. Asher B. Durand, who began as an engraver (even engraving some of Doughty's work) before turning to landscape painting, shared Doughty's commitment to careful observation of nature, though Durand later advocated for even greater fidelity to detail. Doughty's success demonstrated that an American artist could, in fact, build a career painting American landscapes, inspiring countless others to follow suit.

Key Works and Artistic Output

Several paintings stand out as representative of Thomas Doughty's style and contribution. Fanciful Landscape, now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (a gift of the Avalon Foundation), exemplifies his ability to blend observed reality with an idealized, poetic vision. While rooted in American scenery, the composition has a gentle, almost pastoral quality reminiscent of European traditions, showcasing his characteristic soft light and tranquil atmosphere.

Another notable work, Harper's Ferry, Virginia, which was recorded as being handled by Christie's auction house, depicts a specific, recognizable American location known for its dramatic natural beauty where the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers meet. Doughty's interpretation likely focused on the picturesque qualities of the scene rather than its potential for sublime drama. His paintings often carried titles that directly referenced the locations, such as On the Hudson, View in Pennsylvania, or Scene on the Susquehanna, grounding his work in the American geography his audience knew.

Beyond his oil paintings, Doughty was also involved in printmaking. He was a creative lithographer and collaborated with his brother John Doughty on the publication of The Cabinet of Natural History and American Rural Sports between 1830 and 1833. This monthly periodical featured lithographs of American flora, fauna, and sporting scenes, many after Doughty's own drawings. This venture further demonstrates his commitment to disseminating images of American nature to a wider public and highlights his versatility as an artist working across different media.

Career Path and Recognition

Throughout his career, Thomas Doughty moved between several major artistic centers on the East Coast. He began his career in Philadelphia, later spent time working in Boston, and eventually settled in New York City, which was rapidly becoming the epicenter of the American art world. His presence in these cities allowed him to exhibit his work, connect with patrons, and participate in the burgeoning artistic communities there. His election as an honorary academician at the National Academy of Design in 1827 was an early mark of success and peer recognition.

Doughty enjoyed considerable popularity, particularly in the 1820s and 1830s. His pleasing, accessible landscapes found a ready market among patrons seeking decorative works for their homes. His paintings were frequently exhibited at institutions like the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Boston Athenaeum. He was prolific, producing a large number of canvases, often variations on his favorite themes and locations.

However, as the Hudson River School evolved, Doughty's quieter, more lyrical style was somewhat eclipsed by the grander, more dramatic, and often more technically brilliant works of the next generation, including painters like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt. These artists tackled vast panoramas, exotic locales, and sublime natural phenomena, capturing the public imagination in a way that Doughty's more intimate scenes perhaps no longer did. Some accounts suggest that Doughty felt overlooked or underappreciated in his later years, struggling to maintain the level of success he had enjoyed earlier. Despite this, his foundational role remained undeniable.

Expanding the Field: Contemporaries and Context

Understanding Thomas Doughty's contribution requires placing him within the broader context of early 19th-century American art. While he pioneered landscape specialization, other artists were also exploring American scenery. Alvan Fisher (1792-1863), his near exact contemporary, worked primarily in Boston and also painted landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits, though perhaps without Doughty's exclusive focus. In Philadelphia, Thomas Birch (1779-1851) was renowned for his marine paintings and coastal views, capturing the interaction between land and sea with skill.

The towering figure who emerged slightly after Doughty's initial success was Thomas Cole (1801-1848). Cole brought a new level of ambition and drama to American landscape painting, often infusing his works with historical or allegorical meaning, as seen in his famous series The Course of Empire and The Voyage of Life. While Doughty focused on the quiet beauty of nature, Cole explored its sublime power and its capacity to convey complex narratives. Cole's influence became immense, shaping the direction of the Hudson River School for decades.

Later Hudson River School artists built upon the foundations laid by Doughty and Cole. Asher B. Durand (1796-1886) championed meticulous realism and plein-air sketching. John Frederick Kensett (1816-1872) and Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) developed Luminism, a style characterized by subtle light effects and serene, contemplative moods, which arguably owes a debt to Doughty's atmospheric concerns. Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) became famous for his vibrant depictions of autumn foliage. The spectacular, large-scale canvases of Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), depicting South America and the American West respectively, represented the culmination and, some argue, the over-ripening of the Hudson River School's ambitions. Doughty's quieter style provides a crucial counterpoint to these later developments.

European Echoes and American Visions

While Doughty was dedicated to American subjects, his work, like that of most American artists of his time, inevitably engaged with European artistic traditions. The idealized compositions and golden light found in the works of 17th-century painters like Claude Lorrain provided a powerful model for elevating landscape from mere topography to poetic expression. The more rugged, dramatic landscapes of Salvator Rosa, another 17th-century Italian painter, offered a different model, one embraced more fully by Thomas Cole but perhaps subtly informing Doughty's occasional depiction of wilder scenery.

The influence of 17th-century Dutch landscape painting, with its emphasis on realism, specific local scenery, and atmospheric effects, can also be seen as a precursor to the kind of detailed yet evocative work Doughty produced. Furthermore, the burgeoning Romantic movement in Europe, particularly in England with artists like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, emphasized emotional response, the power of nature, and often a looser, more expressive handling of paint. While Doughty's style remained relatively controlled, the underlying Romantic sensibility – the focus on feeling, mood, and the spiritual resonance of the natural world – clearly connects his work to these broader international currents.

Doughty's achievement was to synthesize these influences and apply them effectively to the American scene. He filtered European conventions through his own observations and gentle temperament, creating landscapes that felt both familiar and elevated, both American and part of a larger artistic conversation. He helped American audiences see their own country through the lens of established aesthetic values, thereby validating the American landscape as a worthy subject for high art.

Legacy: The Quiet Pioneer

Thomas Doughty's legacy rests firmly on his status as a pioneer. His decision to devote himself entirely to landscape painting was a pivotal moment in American art history. It asserted the importance of the genre and opened the door for the flourishing of the Hudson River School. His quiet, lyrical style, though perhaps less spectacular than that of some successors, captured a specific aspect of the American landscape – its capacity for peace, serenity, and gentle beauty.

His influence extended through his paintings, which were widely seen and collected, and through his prints, which reached an even broader audience. He demonstrated that an artist could find inspiration and subject matter in the immediate surroundings of American rivers, mountains, and forests. He helped cultivate a taste for landscape art among American patrons, creating a market that would support subsequent generations of artists.

While his fame may have been eclipsed during his lifetime and after by artists with bolder styles or grander visions, art historians recognize his crucial role. He stands as a foundational figure, an artist whose dedication and sensitivity helped shape the course of American art. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their tranquil charm, their delicate rendering of light and atmosphere, and their sincere affection for the American land. They offer a valuable perspective on the early development of American cultural identity and the enduring human connection to the natural world. Thomas Doughty may have been a quiet pioneer, but his impact was profound and lasting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Serenity

Thomas Doughty occupies an essential, if sometimes understated, position in the history of American art. As the nation's first full-time landscape specialist, he bravely charted a course away from the dominance of portraiture, asserting the value and beauty of the American wilderness as a primary subject for artistic endeavor. His work, characterized by its lyrical mood, atmospheric sensitivity, and focus on the tranquil aspects of nature, provided a crucial foundation for the Hudson River School.

Working in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, Doughty captured the specific scenery of the northeastern United States, translating the visual language of European landscape traditions into a distinctly American idiom. His paintings of the Hudson, Delaware, and Susquehanna rivers, the Catskill and White Mountains, offered audiences idealized yet recognizable visions of their own land, fostering a national appreciation for landscape art. Recognized early with honors like membership in the National Academy of Design, his influence permeated the first generation of Hudson River School painters, including figures like Asher B. Durand.

Though later overshadowed by the more dramatic works of Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, and Albert Bierstadt, Doughty's contribution remains fundamental. His numerous canvases, found today in collections like the National Gallery of Art, continue to resonate with their quiet charm and poetic sensibility. Thomas Doughty's legacy is that of a true pioneer who not only depicted the American landscape but helped teach Americans how to see it, appreciate it, and value it as a core part of their cultural heritage. His serene visions endure as a testament to the quiet beauty he found in the American wilderness.