Samuel Lancaster Gerry stands as a significant figure in the annals of 19th-century American art. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1813, Gerry lived a long and productive life, passing away in 1891. His legacy is intrinsically tied to the majestic landscapes of New Hampshire, particularly the White Mountains, which he depicted with affection and skill for over six decades. Though largely self-taught, Gerry rose to become a leading member, and indeed a foundational figure, of the White Mountain School of painting, a regional offshoot of the broader Hudson River School movement. His work not only captured the sublime beauty of the American wilderness but also played a role in shaping the cultural identity and promoting the burgeoning tourism of the Granite State.

Gerry's journey into the art world was not one of formal academic training, a common path for many European artists but less unusual in the developing artistic landscape of early 19th-century America. His initial foray into a related field involved a partnership with fellow artist James Burt, operating a sign and decorative painting business in Boston between 1834 and 1839. This practical experience likely honed his skills in handling paint and composition, providing a foundation upon which he would build his fine art career.

Early Explorations and Influences

The year 1835 marked a pivotal moment for Gerry: his first documented visit to the White Mountains. This encounter with the rugged peaks, deep valleys, and crystalline rivers of New Hampshire ignited a passion that would define his artistic output for the rest of his life. The following year, 1836, saw his marriage to Mary Catherine Jewett and the creation of his first known painting featuring a White Mountain subject. From this point forward, the region became his principal muse.

While Gerry lacked formal instruction in an academy setting, he was a keen observer and absorbed influences from prominent American artists of his time. He deeply admired the work of Thomas Cole, often considered the founder of the Hudson River School, whose dramatic and often allegorical landscapes captured the wild spirit of the American continent. Gerry also looked to Asher B. Durand, another leading figure of the Hudson River School, known for his meticulous detail, emphasis on direct observation of nature, and more tranquil, naturalistic scenes. Gerry's style would ultimately synthesize elements from both, blending romantic grandeur with careful attention to topographical accuracy and atmospheric effects.

Gerry's artistic education was further enriched by travel. Like many ambitious American artists of the era, he undertook trips to Europe. These journeys exposed him to the masterpieces of European art history and the diverse landscapes of the Old World. While specific itineraries are not always fully documented, this exposure undoubtedly broadened his artistic horizons, refined his technique, and provided a comparative framework for appreciating the unique character of the American scenery he so loved. He learned from the compositional strategies and palettes of European masters, integrating these lessons into his distinctly American subjects.

The White Mountain School and Gerry's Role

Samuel Lancaster Gerry is inextricably linked with the White Mountain School. This group of artists, flourishing primarily from the 1830s through the 1870s, converged on the White Mountains region each summer, drawn by its accessibility (relative to more distant wilderness areas) and its stunning natural beauty. They established studios in towns like North Conway, Jackson, and Bethlehem, forming a vibrant artistic community. Gerry was not merely a participant; he was a pioneer and a central figure within this movement.

The White Mountain School artists, while diverse in their individual styles, shared a common focus on capturing the specific scenery of the area: Mount Washington's imposing presence, the dramatic notches (Crawford and Franconia), the winding Saco River, the serene lakes like Winnipesaukee, and iconic geological formations. Gerry, along with contemporaries like Benjamin Champney (often considered the 'dean' of the school), Frank Henry Shapleigh, Albert Bierstadt (who visited and painted), John Frederick Kensett, Jasper Francis Cropsey, and Aaron Draper Shattuck, helped define the visual vocabulary associated with this region.

Gerry's leadership role extended beyond his prolific output. He was instrumental in establishing North Conway as an artistic hub. His frequent presence, his welcoming attitude towards fellow artists, and his dedication to depicting the local scenery encouraged others to follow. He spent considerable time painting en plein air (outdoors), making sketches and studies that he would later work up into larger canvases in his Boston studio during the winter months. This practice, championed by Durand and increasingly popular, allowed for a greater sense of immediacy and fidelity to natural light and conditions.

Signature Style and Subjects

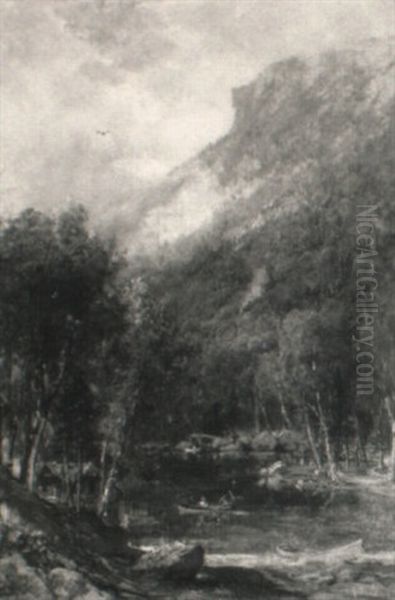

Gerry's artistic style evolved over his long career but consistently balanced Romantic sensibilities with a commitment to realistic detail. His landscapes often possess a sense of awe and grandeur, capturing the sublime power of nature, reminiscent of Thomas Cole. However, they are also grounded in careful observation, reflecting the influence of Asher B. Durand and the broader Hudson River School's emphasis on truthfulness to nature. His brushwork could be detailed and precise, particularly in the foreground elements like rocks, foliage, and water, yet also fluid and expressive in capturing skies and atmospheric perspective.

His palette was typically rich and varied, adeptly capturing the changing light and seasons in the mountains. He skillfully rendered the hazy blues of distant peaks, the vibrant greens of summer foliage, the fiery hues of autumn, and the crisp light on snow-covered winter landscapes. Light plays a crucial role in his compositions, often used dramatically to highlight specific features, create depth, and evoke a particular mood, ranging from tranquil serenity to stormy drama.

While landscapes dominated his oeuvre, Gerry frequently incorporated anecdotal details that added life and narrative interest to his scenes. Small figures – hikers, farmers, Native Americans, artists sketching, or elegantly dressed tourists on horseback – often populate his canvases. These figures serve not only to provide scale but also to situate the landscape within a human context, reflecting the growing tourism in the region that his own paintings helped to stimulate. He often included animals, particularly dogs and horses, rendered with sensitivity. Occasionally, Gerry also turned his hand to other genres, including still life and animal paintings, demonstrating a versatility beyond landscape.

Notable Works

Several of Gerry's paintings have become iconic representations of the White Mountains. Among his most celebrated works is his depiction of The Old Man of the Mountain. This natural rock formation, resembling a human profile high on Cannon Mountain in Franconia Notch, was already a famous landmark. Gerry painted it numerous times, capturing its stoic grandeur against dramatic skies or nestled amidst the surrounding peaks. His images contributed significantly to the Old Man's status as a symbol of New Hampshire (until its unfortunate collapse in 2003).

Another significant work is The Flume, painted around 1882. This canvas depicts a dramatic gorge in Franconia Notch, known for its narrow, water-carved channel and, at the time, a large boulder suspended precariously between its walls (the boulder washed away in a storm in 1883). Gerry captures the cool, moist atmosphere of the gorge, the rushing water, and the towering rock walls, conveying the geological power and unique beauty of the site.

Paintings of Mount Washington, the highest peak in the northeastern United States, were also a recurring theme. He depicted the mountain from various vantage points, capturing its often cloud-shrouded summit and the rugged terrain of the Presidential Range. Works like Mount Washington from North Conway showcase his ability to handle expansive vistas, balancing the majestic scale of the mountains with the pastoral charm of the Saco River valley below. His depictions often included elements like the Mount Washington Cog Railway or the Summit House, documenting human interaction with the formidable peak.

Other notable subjects included Crawford Notch, Echo Lake, Lake Winnipesaukee, and various views along the Saco and Ellis Rivers. A watercolor like At the End of the Day (c. 1880s), showing a scene near Jackson, demonstrates his proficiency in that medium as well, capturing a softer, more intimate aspect of the landscape. Through these works, Gerry created a comprehensive visual record of the White Mountains during a period of significant cultural and environmental change.

The Boston Art Scene and Mentorship

Beyond his extensive work in New Hampshire, Samuel Lancaster Gerry remained deeply connected to the Boston art world throughout his career. He maintained a studio in the city for many years, which served as his base during the non-summer months and a place to finalize the larger compositions based on his outdoor sketches. His presence in Boston facilitated his engagement with the city's burgeoning artistic institutions.

A testament to his standing and organizational abilities was his role in the founding of the Boston Art Club. Around 1854-1855, Gerry, along with fellow artists like Benjamin Champney and possibly Alfred Ordway, established the club as a space for artists to socialize, exhibit their work, and foster a sense of community. Gerry served as the club's president, guiding its early development and helping it become a significant force in Boston's cultural life. The club provided crucial exhibition opportunities outside the more established, but sometimes conservative, Boston Athenaeum.

Gerry was also an active member of the Boston Art Association and exhibited his work frequently at various venues, including the aforementioned Boston Athenaeum and the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association exhibitions. These regular showings kept his work in the public eye and solidified his reputation as one of New England's premier landscape painters.

His influence extended to the next generation of artists. While self-taught himself, Gerry took on the role of mentor and teacher for several aspiring painters. Among his notable students was Joseph Frank Currier, who would later gain recognition for his Barbizon-influenced style. Other artists documented as having studied with Gerry include H. Frances Osborne, Eleanor Fanny Gifford, and Charles Wesley Sanderson. This teaching role underscores Gerry's commitment to fostering artistic talent and contributing to the continuity of the landscape tradition. His friendships and collaborations, like the early venture with James Burt which resulted in the Boston Fire Company series (later engraved by others, including prints based on William Henry Bartlett's work), further illustrate his integration within the artistic network of his time.

Later Career and Legacy

Samuel Lancaster Gerry continued to paint actively into his later years, remaining faithful to the White Mountain subjects that had captivated him for so long. He witnessed significant changes in the American art world during his lifetime. The dominance of the Hudson River School and its regional branches, like the White Mountain School, began to wane in the later decades of the 19th century. New artistic currents, including the influence of the French Barbizon School (seen in the work of artists like George Inness and William Morris Hunt) and the rise of American Impressionism (with figures like Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman), shifted aesthetic preferences towards different styles and subjects.

Furthermore, the expansion of photography provided new ways of documenting landscapes, and the opening of the American West drew artists towards even grander, more exotic scenery, as seen in the monumental canvases of Albert Bierstadt (who also painted the White Mountains) and Thomas Moran. While the appeal of White Mountain scenery endured, the specific style championed by Gerry and his contemporaries gradually fell out of critical favor, perceived by some as overly detailed or picturesque compared to newer trends.

Despite these shifts in taste, Gerry's contribution remains undeniable. His extensive body of work provides an invaluable visual record of 19th-century New Hampshire, capturing not just the topography but also the spirit of the place as perceived by his generation. His paintings celebrated the beauty and accessibility of the American landscape, making it relatable and desirable to a growing audience. His work, disseminated through exhibitions and popular engravings, played a direct role in promoting tourism, shaping how Americans viewed and experienced this part of their natural heritage.

Today, Samuel Lancaster Gerry's paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the New Hampshire Historical Society; the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College; the Brooklyn Museum; and the Toledo Museum of Art, among others. Art historians recognize him as a key figure of the White Mountain School and an important contributor to the broader narrative of American landscape painting. His dedication to his chosen subject, his skillful blending of Romanticism and Realism, and his role within the Boston and North Conway art communities secure his place in American art history.

Conclusion

Samuel Lancaster Gerry's life spanned a transformative period in American art and culture. As a largely self-made artist, he navigated the developing art world of the 19th century, finding his voice in the landscapes of New Hampshire. His dedication to the White Mountains resulted in a body of work that is both a loving portrait of a specific region and a significant contribution to the American landscape tradition. As a founder and leader of the White Mountain School and a central figure in the Boston art scene, his influence extended beyond his own canvases. While artistic styles evolved, Gerry's paintings endure as compelling testaments to the beauty of the natural world and the artistic vision of a painter who dedicated his life to capturing the majesty of the White Mountains. His work continues to resonate, offering viewers a glimpse into the 19th-century American encounter with its wilderness.