William Mason Brown (1828-1898) stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century American art. Primarily recognized for his exceptionally detailed still life paintings, particularly of fruit, Brown's artistic journey also encompassed portraiture and landscape painting, linking him firmly to the traditions of the Hudson River School. His meticulous technique and keen eye for naturalistic representation earned him considerable acclaim during his lifetime, and his works continue to be appreciated for their technical brilliance and quiet beauty. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, style, and legacy of a painter who navigated the shifting artistic currents of his time with remarkable skill.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Troy, New York, in 1828, William Mason Brown began his artistic career not amidst landscapes or fruit bowls, but as a portrait painter. He received his initial training under the tutelage of Abel Buell Moore, a local artist. Brown quickly established himself, becoming one of Troy's most sought-after portraitists. This early phase honed his skills in capturing likeness and detail, foundational elements that would later define his mature work in other genres. The demand for his portraits indicated an early recognition of his technical proficiency within his local community.

However, Brown's artistic interests were not confined to portraiture. Around 1850, seeking broader horizons or perhaps a different mode of artistic expression, he relocated to Newark, New Jersey. This move marked a significant turning point in his career. It was during his time in Newark that Brown began to shift his focus away from the human face and towards the natural world, initially concentrating on landscape painting. This transition aligned him with the prevailing artistic movement of the era in the northeastern United States: the Hudson River School.

Embracing the Landscape: The Hudson River School Connection

William Mason Brown emerged as a notable figure among the second generation of Hudson River School artists. This movement, largely inspired by the majestic scenery of the American Northeast, celebrated the beauty and sublimity of nature. Brown's landscape work reflects the influence of the school's pioneers, such as the renowned Thomas Cole, whose dramatic and allegorical landscapes set a high standard. Brown, like contemporaries such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford, sought to capture the specific character and atmosphere of the American wilderness.

His landscapes often featured the detailed foregrounds, expansive skies, and carefully rendered atmospheric effects characteristic of the Hudson River School style. He depicted the rolling hills, tranquil rivers, and lush forests of areas like the Hudson River Valley, often imbuing them with a sense of romanticism and serene beauty. These works demonstrated his growing mastery over the depiction of light, texture, and space within the natural environment. While accomplished, his landscape period would eventually serve as a bridge to the genre where he would achieve his most lasting fame.

The meticulous attention to detail evident in his landscapes, perhaps influenced by the Ruskinian dictum of "truth to nature" that was gaining traction in American art circles through the writings of the English critic John Ruskin, foreshadowed the intense focus he would later bring to still life. Artists like Asher B. Durand, another key Hudson River School figure, also emphasized direct observation and detailed rendering of nature, creating a fertile ground for Brown's evolving style.

A Pivotal Shift: The Turn to Still Life

By the 1860s, William Mason Brown made another significant shift in his artistic focus, moving decisively from landscape painting to still life. While the exact reasons for this transition remain speculative, several factors likely played a role. The art market was evolving, and there was a growing appreciation and demand for meticulously rendered still life paintings, which could be displayed more easily in domestic interiors than large landscapes. Furthermore, the detailed, almost microscopic focus required for still life may have appealed to Brown's innate technical abilities and his interest in capturing the tangible reality of objects.

This move placed him within a rich tradition of American still life painting, stretching back to the Peale family, particularly Raphaelle Peale, in the early 19th century. However, Brown's approach differed from the often simpler, more austere arrangements of earlier painters. He embraced a heightened realism and a focus on the sensuous qualities of his subjects, particularly fruit. This transition occurred during a period when still life painting in America was experiencing a resurgence, with artists like Severin Roesen creating elaborate, bountiful compositions.

Brown settled in Brooklyn, New York, which became his base for the remainder of his career. This vibrant borough provided a supportive environment, with a growing community of artists and patrons. His decision to specialize in still life proved fortuitous, as his works in this genre quickly found favor with collectors and critics, leading to significant commercial success and establishing his reputation on a national level.

The Art of Still Life: Precision and Realism

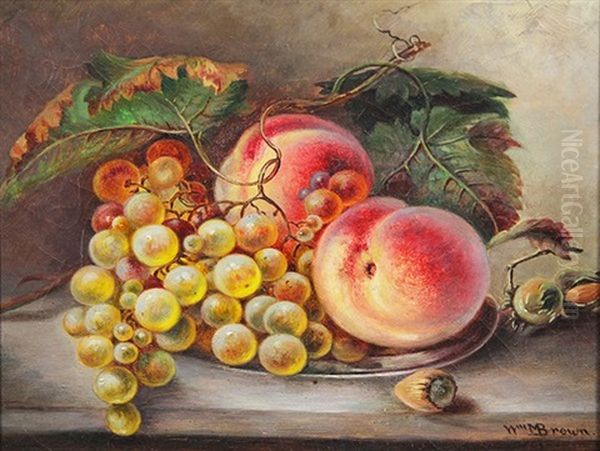

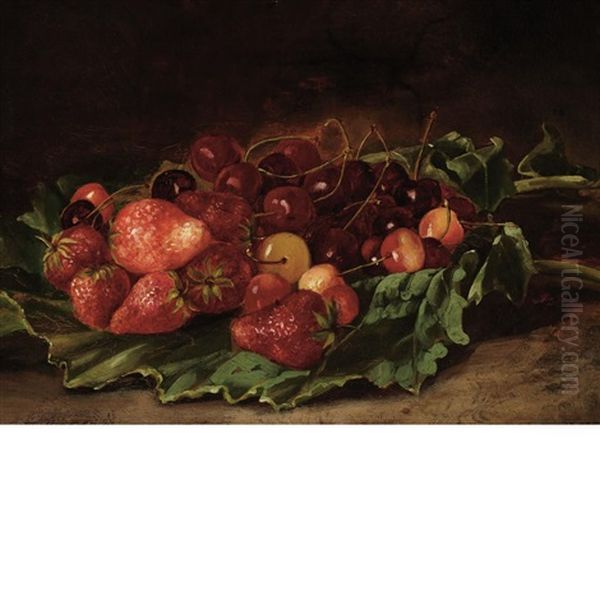

William Mason Brown's still life paintings are celebrated for their extraordinary realism and meticulous detail. He primarily focused on fruit – peaches, grapes, berries, and cantaloupes were frequent subjects – often depicted nestled in natural settings like mossy banks or forest floors, or sometimes arranged in baskets. His technique involved careful layering of glazes to achieve luminous color and precise rendering of textures, from the fuzzy skin of a peach to the dewy surface of a grape.

His style shows an affinity with the principles championed by John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who advocated for intense observation and detailed representation of the natural world. While not formally part of the American Pre-Raphaelite movement, which included artists like William Trost Richards and John William Hill, Brown's work shared its emphasis on empirical accuracy and intricate detail. Some art historians also note a possible influence from contemporary European academic painters like the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his highly polished finish and focus on texture over visible brushwork.

Brown's compositions are typically intimate and closely focused, drawing the viewer's eye directly to the textures, colors, and forms of the fruit. He masterfully manipulated light and shadow to enhance the sense of volume and realism, making the fruit appear almost tangible. Unlike the sometimes overflowing, complex arrangements of Severin Roesen, Brown's compositions often possess a quieter, more focused intensity. His work stands alongside that of other notable 19th-century American still life painters such as John F. Francis and Martin Johnson Heade, each contributing uniquely to the genre.

Masterworks and Recognition

Several of William Mason Brown's still life paintings have become iconic representations of his style. Still Life with Cantaloupe (c. 1880) exemplifies his ability to render the distinct textures of the melon's rind and the juicy flesh within. Peaches and Grapes showcases his signature subjects, capturing the soft blush of the peaches and the translucent quality of the grapes with remarkable fidelity. Another notable work, Strawberries Strewn on a Forest Floor, integrates the fruit into a naturalistic setting, highlighting his skill in depicting both the delicate berries and the surrounding foliage and earth.

Perhaps his most famous work is Apples and Lilacs. This painting is lauded for its elegant composition, rich coloration, and the juxtaposition of the crisp apples with the delicate blossoms. Its enduring appeal is evidenced by its adaptation into popular cross-stitch patterns, demonstrating its resonance beyond traditional art circles. Another commercially successful piece was A Basket of Peaches Upset, which gained widespread recognition through chromolithographic reproductions.

The popularity of such reproductions, often produced by firms like Currier & Ives, significantly broadened Brown's audience and cemented his reputation. These prints made his detailed and appealing images accessible to a wider public, contributing to his commercial success. His work was regularly exhibited at prestigious venues, including the National Academy of Design in New York and the Brooklyn Art Association, institutions central to the American art world. His talent received formal recognition when he was awarded a medal at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876, a major international event showcasing American arts and industry.

Community and Collaboration: Brooklyn's Art Scene

Beyond his personal artistic practice, William Mason Brown was an active participant in the burgeoning art community of Brooklyn. In 1859, demonstrating a commitment to fostering local arts infrastructure, he collaborated with fellow artist William Hart, another prominent landscape painter associated with the Hudson River School, to co-found the Brooklyn Art Association. This organization played a crucial role in exhibiting works by local and national artists and eventually evolved into the Brooklyn Museum, one of the city's major cultural institutions.

Their collaboration continued, and in 1866, Brown and Hart were instrumental in establishing the Brooklyn Academy of Design. This institution aimed to provide formal art instruction, further nurturing the growth of artistic talent within the borough. Brown's involvement in these organizations highlights his dedication not only to his own work but also to the collective development and promotion of the arts in his adopted home city. His engagement helped solidify Brooklyn's reputation as an important center for artistic activity in the latter half of the 19th century.

His participation in these associations placed him in regular contact with numerous other artists of the day, fostering an environment of exchange and mutual influence. While the competitive nature of the art market certainly existed, these collaborative efforts underscore a spirit of community building among artists like Brown, Hart, and their contemporaries, such as George Inness and Jasper Francis Cropsey, who were also active in the New York and Brooklyn art scenes.

Beyond the Canvas: Innovation and Activism

William Mason Brown's life extended beyond the confines of the art studio, revealing a man of diverse interests and strong convictions. Demonstrating a practical and inventive mind, he secured patents for inventions unrelated to painting: "Brown's Patent Fruit-Picker" and "a new and improved sofa bed." These innovations suggest a mind engaged with problem-solving and mechanical design, complementing his meticulous approach to painting.

Furthermore, historical accounts indicate that Brown was involved in the Underground Railroad, the clandestine network dedicated to helping enslaved African Americans escape to freedom. This activity, inherently dangerous and requiring great courage and discretion, points to a deep-seated commitment to abolitionism and social justice. While details of his specific actions remain scarce due to the secretive nature of the network, his participation aligns him with other artists and intellectuals of the era who actively opposed slavery.

On the domestic front, Brown's personal life appears relatively understated despite his professional success. He was married to Martha, and there are mentions of her operating a successful upholstery and carpet-making workshop, possibly in Worcester, Massachusetts, suggesting family connections or activities extending beyond Brooklyn. His son, Charles Brown, followed a path related to craftsmanship, becoming a talented tailor and interior decorator, indicating a familial inclination towards skilled work and design. These facets of his life paint a picture of a multifaceted individual engaged with his community, family, and the pressing social issues of his time.

Legacy and Influence

William Mason Brown died of heatstroke in Brooklyn in 1898, at the age of 70. He left behind a significant body of work that continues to be studied and admired. His primary legacy lies in his contribution to American still life painting. He brought a level of detailed realism and technical polish to the genre that was highly influential and popular during his lifetime. His ability to capture the sensuous qualities of fruit and natural objects set a benchmark for illusionistic representation.

His works are held in the collections of numerous important American museums, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the art collections of various universities. The continued presence of his paintings in these institutions ensures their accessibility to new generations of viewers and scholars. While artistic tastes shifted towards Impressionism and Modernism around the turn of the century, Brown's work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of meticulous realism and the beauty found in the careful observation of nature.

As an artist who successfully navigated the transition from landscape to still life, Brown occupies a unique position in 19th-century American art history. He represents a link between the romantic landscape tradition of the Hudson River School and the highly refined realism that characterized much of the still life painting of the Gilded Age. His dedication to craft, his community involvement, and his quiet engagement with social issues contribute to a portrait of a significant and principled American artist.

Conclusion

William Mason Brown was more than just a painter of peaches and grapes; he was a versatile artist whose career traversed several key phases of 19th-century American art. From his beginnings as a portraitist in Troy to his contributions to the Hudson River School landscape tradition, and finally to his mastery of highly detailed still life, Brown consistently demonstrated exceptional technical skill and a deep appreciation for the visual world. His still life paintings, in particular, stand out for their jewel-like precision and almost photographic realism, securing his place as one of the foremost practitioners of the genre in America. Through his art, his community building, and his personal convictions, William Mason Brown left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of his time.