The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were a period of fascinating artistic experimentation and diverse tastes across Europe. While grand history paintings and formal portraiture often dominated the narratives of art history, other, more unique and sometimes ephemeral art forms also flourished, capturing the imagination of both aristocratic patrons and the wider public. Among the practitioners of one such distinctive craft was Benjamin Zobel, a German-born artist who made his name in London as a master of "marmotinto," or sand painting. His work, though perhaps less widely known today than that of some of his oil-painting contemporaries, offers a captivating glimpse into the artistic curiosities and decorative arts of the Georgian era.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Benjamin Zobel was born in 1762 in Memmingen, a town in Swabia, a region in present-day Germany. His early life was not initially directed towards the fine arts in the conventional sense. Instead, he was involved in his family's business, which was confectionery. This background, seemingly distant from the world of painting and sculpture, may have inadvertently provided him with a foundational understanding of working with granular materials, a skill that would later define his artistic career. Sugar, like sand, requires a delicate touch and an understanding of its properties when used for decorative purposes.

Despite his beginnings in the confectionery trade, Zobel's artistic inclinations eventually led him to pursue formal training. He traveled to Holland, a country with a rich artistic heritage, particularly renowned for its meticulous detail in still life and genre painting. There, Zobel studied the art of miniature painting. This discipline would have honed his skills in precision, careful application of color, and working on a small scale, all of which would prove valuable in his later specialization.

Arrival in London and the Rise of a Sand Painter

In 1784, Benjamin Zobel made a significant move to London. England, at this time, was a vibrant cultural hub, and London was a magnet for artists and craftsmen from across Europe. It was here that Zobel transitioned from miniature painting to the more unconventional art of sand painting, becoming known as a prominent "sand-painter." This technique, which he termed "marmotinto" (derived from "marmo" for marble and "tinto" for tinted, alluding to the use of colored marble dusts or sands), was a unique practice that garnered considerable attention.

Zobel's skill in this medium quickly attracted an elite clientele. Among his most notable patrons was King George III, a monarch known for his interest in the arts and sciences. The patronage of the royal family and other members of the British aristocracy significantly elevated Zobel's status and the desirability of his sand paintings. His works were sought after for their novelty, their intricate beauty, and the sheer skill involved in their creation.

The Delicate Art of Marmotinto

The technique of marmotinto, as practiced by Zobel, was a meticulous and demanding process. It involved using finely ground colored sands, marble dust, and sometimes even sugar, carefully sprinkled or poured onto a prepared surface, typically a wooden panel or a plasterboard. The artist would first sketch an outline and then apply an adhesive, such as gum arabic or another type of glue, to small sections at a time. The colored sands were then delicately applied to these sticky areas, building up the image layer by layer.

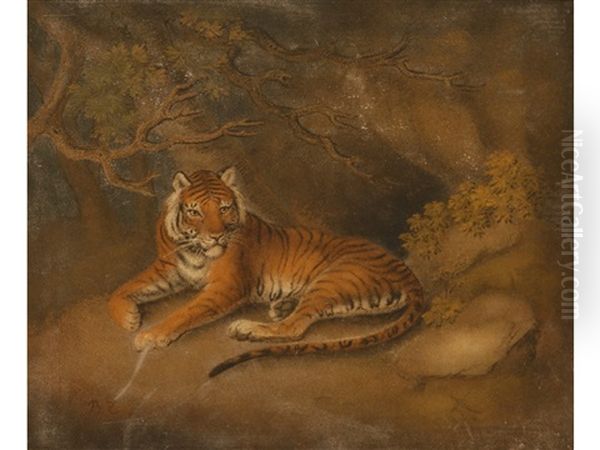

Once the composition was complete, the entire work would be carefully fixed to make it more permanent, though the inherent fragility of the medium meant that many such works were susceptible to damage over time. Zobel's innovation lay in developing methods to create relatively durable sand paintings that could be framed and displayed much like traditional paintings. His subjects were varied, often focusing on animal scenes, still lifes, and occasionally landscapes, reflecting popular tastes of the period.

This art form had connections to the ephemeral "table-decking" traditions of the era, where elaborate, temporary designs were created on dining tables using colored sugars and sands for banquets and special occasions. Zobel, with his confectionery background, would have been familiar with such practices. However, he elevated this transient craft into a more lasting art form, creating fixed pictures that could be admired for years.

Notable Works and Artistic Themes

While many of Benjamin Zobel's sand paintings may have been lost to time due to their delicate nature, records and surviving examples attest to his skill and the range of his subjects. His works often drew inspiration from popular contemporary artists or depicted subjects favored by his patrons.

One notable category was animal portraiture. An example cited is "King George's Dog, Nelson," which would have been a commission directly appealing to the King's personal interests. Such pieces demonstrate the intimate connection between artist and patron in the 18th century.

Zobel also created works inspired by other artists, a common practice at the time. "Pigs in the Morland Style" suggests an homage or an interpretation of the rustic genre scenes popularized by George Morland (1763-1804), a contemporary English painter renowned for his depictions of rural life, animals, and sentimental subjects. Morland's work was widely reproduced through engravings, making his style accessible and influential.

Another intriguing title is "Tiger after George Stubbs." George Stubbs (1724-1806) was one of Britain's foremost animal painters, celebrated for his anatomically precise and powerful depictions of horses, lions, tigers, and other creatures. A sand painting by Zobel based on a work by Stubbs would have been a technical feat, translating Stubbs's painterly realism into the granular medium of sand. The original reference mentioned "George Stuard," but it is highly probable that this refers to the celebrated George Stubbs, given the subject matter.

Other works attributed to him include "Vulture and Snake," indicating a taste for dramatic or exotic animal subjects, which were gaining popularity as European exploration and colonialism brought images and accounts of faraway lands and their fauna to public attention. His repertoire also included still lifes, a genre that allowed for intricate displays of texture and color, well-suited to the sand painting technique.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu in Georgian England

Benjamin Zobel practiced his art in a London teeming with artistic talent and diverse practices. The Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768 with Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) as its first president, was the dominant force in the British art world, promoting history painting and portraiture in the Grand Manner. Reynolds, along with his rival Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), defined the pinnacle of British painting during much of Zobel's early career in London.

Other prominent figures included George Romney (1734-1802), a highly fashionable portrait painter, and Swiss-born Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), known for his dramatic and often unsettling depictions of literary and mythological scenes. The visionary artist and poet William Blake (1757-1827) was also active, though his highly individualistic work stood apart from mainstream tastes.

In the realm of landscape, artists like Paul Sandby (1731-1809), often called the "father of English watercolour," were popularizing topographical views, while the early careers of future giants like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837) were just beginning to unfold during Zobel's active period. Decorative arts were also flourishing, with figures like Josiah Wedgwood revolutionizing ceramics.

Within this rich artistic environment, Zobel's sand painting occupied a niche. It was a specialized craft that appealed to a taste for the curious, the ingenious, and the decorative. He was not alone in Europe in practicing sand art; artists like the German Georg Haas and Friedrich Schweikhardt were also known for similar techniques. However, Zobel was a key figure in popularizing and refining fixed sand painting in England.

Legacy and Historical Significance of Benjamin Zobel

Benjamin Zobel passed away in 1831. His primary contribution to art history lies in his mastery and popularization of marmotinto in England. He transformed what might have been considered a transient craft associated with temporary decorations into a recognized, albeit niche, art form capable of producing lasting works. His patrons, including royalty, attest to the high regard in which his unique skill was held.

The very nature of sand painting – its reliance on particulate matter and adhesives – means that it is an inherently fragile medium. This fragility has undoubtedly contributed to the loss of many works from this period, making surviving examples by Zobel and his contemporaries particularly valuable as records of this unusual artistic practice. His work is a testament to the diverse forms of artistic expression that flourished in the Georgian era, beyond the more canonical forms of oil painting and sculpture. He demonstrated that artistic merit could be found in unconventional materials and techniques, appealing to a sense of wonder and craftsmanship.

Auction records indicate that Zobel's works, and those of his school, still appear on the market, though infrequently. For instance, a pair of sand pictures titled "Lion and Tiger" were noted at a Bonhams auction, and another piece, "The Hermit," at a Heritage auction. These sales, though perhaps modest in value compared to major oil paintings, demonstrate a continued collector interest in these rare and curious artworks.

A Necessary Clarification: Fernando Zóbel de Ayala y Montojo

It is crucial at this juncture to address a potential point of confusion arising from the similarity of names. Much of the information regarding abstract art styles, specific techniques like using surgical syringes, interactions with 20th-century artists, and certain museum collections pertains not to Benjamin Zobel (1762-1831) but to a much later artist: Fernando Zóbel de Ayala y Montojo (1924-1984).

Fernando Zóbel was a highly influential Spanish-Filipino painter, a key figure in the development of Spanish abstract art in the post-war period. He was also a scholar, art collector, and museum founder. His artistic journey and contributions are distinct from those of Benjamin Zobel, the 18th/19th-century sand painter.

Fernando Zóbel: An Abstract Pioneer

Fernando Zóbel was born in Manila, Philippines, into a prominent family. He studied philosophy and literature at Harvard University, where he began to paint seriously. His early work showed influences from artists like Mark Rothko (1903-1970) and other Abstract Expressionists he encountered in America. He was particularly struck by Rothko's use of color and its emotional impact, an experience that profoundly shaped his own artistic direction.

His style evolved significantly over his career. Early phases featured vibrant colors and organic abstract forms, sometimes showing the influence of artists like Henri Matisse (1869-1954). However, from the 1960s onwards, Fernando Zóbel moved towards a more refined, almost calligraphic style of non-representational art. He became known for his "Saeta" (Arrow) series, characterized by dynamic, thin lines often created with surgical syringes to achieve unparalleled precision and control over the flow of paint. These works often employed a limited color palette, particularly in his "Serie Negra" (Black Series), which emphasized the abstract expressive power of the line itself, sometimes evoking a sense of Oriental aesthetics, Zen Buddhism, and a meditative tranquility.

Fernando Zóbel's Artistic Dialogue and Influence

Fernando Zóbel was deeply engaged with the international art scene. He formed lasting friendships and artistic dialogues with many contemporaries. His relationship with the American painter and printmaker Bernard Childs (1910-1985) was significant; Zóbel learned engraving techniques from Childs and even painted a portrait of Childs working. He also maintained a long correspondence with Eric Pfeufer and his family, particularly Reed Pfeufer, an artist herself.

In Spain, Fernando Zóbel became a central figure in the abstract art movement. He was associated with the influential "El Paso" group, which included artists like Manolo Millares (1926-1972), Rafael Canogar (b. 1935), Luis Feito (1929-2021), and Antoni Tàpies (1923-2012), though he was not a formal member. These artists sought to revitalize Spanish art in the Franco era through abstraction.

Fernando Zóbel's Legacy: Museums and Collections

Fernando Zóbel was not only a creator but also a passionate collector and promoter of art. One of his most enduring legacies is the founding of the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español (Museum of Spanish Abstract Art) in Cuenca, Spain, in 1966. Housed in the city's famous "hanging houses" (Casas Colgadas), the museum was established with Zóbel's personal collection of works by his Spanish contemporaries. He later donated his collection and the museum to the Juan March Foundation, which continues to manage it.

He also played a vital role in the Philippines, donating his collection of Filipino modernist art and his extensive library of art books to the Ateneo de Manila University, leading to the establishment of the Ateneo Art Gallery in 1960 (officially opened 1961). This institution became a pioneering museum of modern art in the Philippines. His works are held in major collections worldwide, including the Tate in London, the Reina Sofía in Madrid, and numerous museums in the Philippines and the United States.

Fernando Zóbel's art is characterized by its intellectual rigor, lyrical abstraction, and a profound exploration of memory, nature, and the act of painting itself. Works like "Virevia" (1960) exemplify his ability to transform observed reality or remembered landscapes into poetic visual experiences. His exploration of light, space, and movement through meticulously controlled lines and subtle color harmonies secured his place as a major figure in 20th-century abstract art.

Distinguishing Two Artists, Two Eras, Two Distinct Legacies

It is evident, therefore, that Benjamin Zobel, the 18th-century German sand painter in London, and Fernando Zóbel, the 20th-century Spanish-Filipino abstract artist, represent two entirely different figures in art history, separated by time, geography, artistic medium, and style.

Benjamin Zobel's legacy is tied to the specific and unusual craft of marmotinto, a decorative art form that enjoyed a period of popularity in Georgian England. His patrons included the highest echelons of society, and his work is valued for its ingenuity and as a rare example of a delicate art. He operated within a world of burgeoning scientific inquiry and a taste for the novel, where craftsmanship was highly prized. His contemporaries were figures like Reynolds, Gainsborough, Stubbs, and Morland, whose works defined British art of that era.

Fernando Zóbel, on the other hand, was a modernist, an intellectual artist working in the international language of abstraction. His contributions lie in his innovative painting techniques, his influential role in the Spanish and Filipino art scenes, and his significant work as a collector and museum founder. His peers and influences included giants of 20th-century art like Rothko and Matisse, and he was a contemporary of the leading figures of Spanish Informalism.

Conclusion: The Enduring Fascination of Benjamin Zobel's Marmotinto

Returning to Benjamin Zobel (1762-1831), his unique artistic path from confectionery to miniature painting and finally to the specialized art of marmotinto highlights the diverse avenues for artistic expression available in the Georgian period. While not a painter in the conventional sense of oils on canvas, his skill in manipulating colored sands to create lasting images of animals, still lifes, and scenes earned him royal patronage and a distinct place in the annals of decorative arts.

His work serves as a reminder that art history is not solely composed of grand narratives and monumental masterpieces, but also of intricate crafts, innovative techniques, and artists who, like Benjamin Zobel, captured the imagination of their time through unique and often ephemeral means. The surviving examples of his sand paintings are precious artifacts, offering a tangible connection to a fascinating, if less-trodden, byway of art history, and a testament to the enduring human desire to create beauty from the materials at hand, however unconventional.