Darío de Regoyos y Valdés (1857-1913) stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of Spanish art, a visionary who bridged the gap between traditional Spanish painting and the burgeoning modern art movements of Europe. Born in Ribadesella, Asturias, his artistic journey took him from the academic halls of Madrid to the avant-garde circles of Brussels and Paris, making him one of the few Spanish artists of his generation to be deeply integrated into the international art scene. Regoyos is celebrated for his unique interpretation of Impressionism and Pointillism, his evocative depictions of the Spanish landscape, and his critical exploration of Spanish society through the "España Negra" series. His work, often characterized by a profound sensitivity to light and atmosphere, offers a multifaceted view of Spain at the turn of the 20th century, capturing both its vibrant beauty and its somber realities.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Darío de Regoyos was born into an environment that, while not directly artistic, was intellectually stimulating. His father was a prominent architect, Darío de Regoyos y Molenillo, which perhaps instilled in the young Regoyos an appreciation for structure and form. His early artistic inclinations led him to Madrid, the heart of Spain's art world, where he enrolled at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. There, he studied under Carlos de Haes, a Belgian-born landscape painter who had a significant impact on a generation of Spanish artists by promoting plein air painting and a more naturalistic approach to landscape. De Haes's teachings encouraged a departure from the romanticized, studio-bound landscapes that had previously dominated Spanish art, urging students to observe nature directly.

This initial training in Madrid provided Regoyos with a solid academic foundation. However, like many aspiring artists of his time, he felt the pull of artistic centers beyond Spain. The allure of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world, was strong, but it was Brussels that would first become his home abroad and a crucial crucible for his artistic development. This move marked a significant step in his journey towards embracing more progressive artistic ideas.

The Brussels Connection: L'Essor and Les XX

In 1879, Regoyos moved to Brussels, a city buzzing with artistic innovation and a spirit of rebellion against academic conventions. This was a transformative period for him. He quickly immersed himself in the local art scene, befriending Belgian artists like the sculptor Constantin Meunier and painters such as Frantz Charlet and Théo van Rysselberghe. He also studied under Joseph Quinaux, a landscape painter known for his realistic depictions of the Belgian countryside.

His involvement with avant-garde groups was crucial. In 1881, Regoyos became a member of "L'Essor" (The Flight, or The Rise), a progressive artistic circle that aimed to break free from academic constraints and promote new artistic expressions. This group provided a platform for artists experimenting with Realism and early forms of Impressionism.

Even more significantly, Regoyos was a founding member of "Les XX" (The Twenty), established in 1883. This group, led by Octave Maus, was one of the most influential avant-garde societies in Europe. Les XX organized annual exhibitions that showcased not only the work of its Belgian members (including James Ensor, Fernand Khnopff, and Théo van Rysselberghe) but also invited leading international artists. Through Les XX, Regoyos came into direct contact with the works and, in some cases, the persons of French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac. Auguste Rodin, the revolutionary sculptor, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler also exhibited with Les XX. Regoyos was the only Spanish artist among the founding members, a testament to his early embrace of international modernism. His participation in Les XX until its dissolution in 1893 was instrumental in shaping his artistic vision and connecting him to the forefront of European art.

España Negra: A Critical Vision of Spain

While deeply engaged with European modernism, Regoyos remained profoundly connected to his homeland. A significant and distinctive phase of his work is associated with the concept of "España Negra" (Black Spain). This term, popularized in the late 19th century, referred to a vision of Spain characterized by its perceived backwardness, poverty, superstition, and somber traditions, often contrasting with the sunnier, more romanticized image of the country.

Regoyos embarked on a series of travels throughout Spain, often accompanied by the Belgian Symbolist poet Émile Verhaeren. Their collaboration resulted in the book "España Negra," published in 1899, with illustrations by Regoyos. This project allowed him to explore the less picturesque, more austere aspects of Spanish life and landscape. His paintings from this period often depict desolate landscapes, somber religious processions, scenes of rural poverty, and the stark realities of life in provincial Spain. Works like Victims of the Fiesta (critiquing bullfighting) and Good Friday in Castile (Procesión de Viernes Santo en Castilla) exemplify this phase. The latter, now in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, powerfully juxtaposes a traditional religious procession with a modern train speeding across a viaduct in the background, symbolizing the clash between tradition and modernity.

The "España Negra" series is not merely a collection of dark scenes; it is a profound social commentary. Regoyos used a palette that often leaned towards darker tones – greys, browns, and muted greens – to convey the solemnity and sometimes oppressive atmosphere of these subjects. His approach was not one of detached observation but of empathetic engagement, revealing a deep understanding of the complexities of Spanish identity. This body of work distinguished him from many of his Spanish contemporaries, who were often more focused on luminous, optimistic depictions of Spain, such as those by Joaquín Sorolla.

Embracing Light: Impressionism and Pointillism

Parallel to his exploration of "España Negra," Regoyos was keenly interested in the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist concern with light and color. His time in Brussels and his connections with Les XX exposed him directly to these revolutionary techniques. He was particularly drawn to the work of Camille Pissarro, whose influence can be seen in Regoyos's handling of light and his broken brushwork. He also experimented with Pointillism (or Divisionism), a technique pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, which involved applying small, distinct dots of pure color to the canvas, allowing the viewer's eye to optically mix them.

Regoyos adopted Pointillism with a certain flexibility. While he produced some works that strictly adhered to the technique, such as Fishing Nets (Redes de pesca), he often integrated pointillist touches into a broader Impressionistic style. He found the meticulousness of pure Pointillism somewhat constraining for his desire to capture fleeting atmospheric effects quickly. Nevertheless, the principles of optical color mixing and the heightened luminosity achieved through these methods significantly impacted his work. His landscapes from the 1890s onwards often shimmer with vibrant color and light, a stark contrast to the somber tones of the "España Negra" series. He sought to capture the specific light of different regions of Spain, from the misty greens of the Basque Country to the brilliant sunshine of Andalusia.

Works like The Concha, Night-time (La Concha, nocturno) or Plaza de Toros, Dax (Bullring in Dax) showcase his ability to capture varied light conditions and atmospheres. He was less interested in the scientific rigor of Seurat and more in the expressive potential of color and light to convey emotion and sensation. This makes him a unique figure, one who adapted French innovations to a distinctly Spanish sensibility.

Travels and Depictions of the Spanish Landscape

Regoyos was an inveterate traveler. His journeys were not merely for leisure but were integral to his artistic practice. He painted extensively throughout Spain, capturing the diverse landscapes of the Basque Country, Castile, Aragon, Andalusia, and Catalonia. He also traveled and painted in France, Belgium, Holland, and Italy. This constant movement provided him with a rich array of subjects and allowed him to study different light conditions and local customs.

His landscapes are rarely just picturesque views. They often contain elements of human activity or the imprint of human presence, whether it be a rural village, a working port, or the then-modern motif of a train. The train, a symbol of progress and industrialization, appears in several of his works, sometimes integrated harmoniously into the landscape, at other times suggesting a tension between the old and the new, as seen in Good Friday in Castile.

In the Basque Country, where he spent considerable time, he painted scenes of coastal towns like Pasaia and Bermeo, capturing the humid atmosphere and the vibrant life of the fishing communities. His depictions of Granada, particularly in his later years, show a fascination with the interplay of light and shadow in the narrow streets and courtyards, as well as the lush gardens of the Alhambra. Works such as Almond Trees in Blossom (Almendros en flor) or Landscape of Elorrio reveal his mastery in conveying the essence of a place through light, color, and atmosphere. He was adept at capturing the subtle nuances of changing seasons and times of day.

Later Years and Artistic Maturity

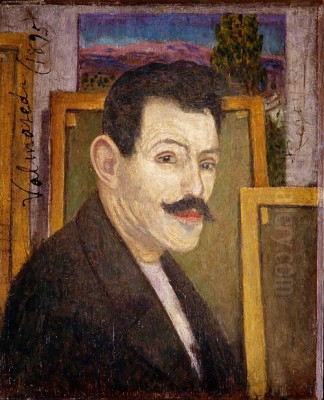

In the early 20th century, Regoyos continued to paint with vigor, though his health began to decline. He settled for a period in Granada and later in Barcelona. His style in these later years consolidated his Impressionistic and Pointillist explorations into a very personal idiom. His palette often became brighter, and his brushwork more fluid and expressive. He continued to paint landscapes, but also produced still lifes and portraits.

Despite his significant contributions and his connections with the European avant-garde, Regoyos did not achieve widespread fame or financial success in Spain during his lifetime. Spanish art taste at the time often favored either the grand historical paintings of the academic tradition or the sun-drenched, optimistic regionalism of painters like Joaquín Sorolla or the more dramatic, Goya-esque realism of Ignacio Zuloaga. Regoyos's more subtle, introspective, and sometimes critical approach found a limited audience initially.

However, he was respected within certain artistic circles and continued to exhibit. He played a role in organizing an exhibition of Spanish modern art in Bilbao, aiming to promote contemporary Spanish art abroad, particularly in France and Belgium. His dedication to his artistic vision, even in the face of indifference or financial hardship, was unwavering. He passed away in Barcelona in 1913 at the age of 56.

Key Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Regoyos's oeuvre, representing different facets of his artistic journey:

Good Friday in Castile (Procesión de Viernes Santo en Castilla) (c. 1904): A seminal work from his "España Negra" period, this painting, housed in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, depicts a solemn religious procession in a stark Castilian landscape, with a modern train crossing a viaduct above. It encapsulates the tension between tradition and modernity, faith and progress, that characterized Spain at the time. The somber colors and elongated figures contribute to the painting's melancholic and critical tone.

The Concha, Night-time (La Concha, nocturno) (c. 1906): This painting of the famous bay in San Sebastián showcases Regoyos's mastery of capturing nocturnal light and atmosphere. Using Impressionistic and Pointillist techniques, he creates a shimmering, evocative scene where artificial lights reflect on the water, contrasting with the deep blues and purples of the night sky. It demonstrates his ability to find beauty and poetry in urban settings.

Victims of the Fiesta (Las Víctimas de la Fiesta) (c. 1894): Another key "España Negra" piece, this work offers a stark critique of bullfighting, focusing not on the spectacle but on the dead or dying horses, victims of the bull. It’s a powerful anti-romantic statement on a cherished Spanish tradition, reflecting a humanitarian sensibility.

Fishing Nets (Redes de pesca): An example of his engagement with Pointillism, this work demonstrates his ability to use dots of color to create a vibrant, luminous surface, capturing the texture of the nets and the play of light.

Almond Trees in Blossom (Almendros en flor) (c. 1905): Representing his later, more luminous phase, this painting, likely from his time in Andalusia, is a celebration of spring and the beauty of nature. The delicate rendering of the blossoms and the bright, clear light reflect a more optimistic and lyrical sensibility, achieved through his refined Impressionistic technique.

Landscape, Environs of Pancorbo (Paisaje, alrededores de Pancorbo) (1908): This work shows his continued dedication to landscape painting, capturing the rugged beauty of the Spanish interior with a vibrant palette and dynamic brushwork, demonstrating his ability to convey the specific character of a location.

These works, among many others, are now found in major Spanish museums, including the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (which holds a significant collection), the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, and the Carmen Thyssen Museum in Málaga.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Regoyos's career was marked by significant interactions with a wide array of artists, writers, and intellectuals. In Brussels, his friendships with Constantin Meunier, Théo van Rysselberghe, James Ensor, and other members of Les XX were formative. These artists shared a commitment to artistic independence and experimentation. His collaboration with Émile Verhaeren on "España Negra" was particularly fruitful, demonstrating a cross-pollination between literature and the visual arts.

In Paris, he was acquainted with Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, and Georges Seurat, whose artistic innovations directly influenced his own. He also knew Spanish artists living or exhibiting in Paris, such as Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas, leading figures of Catalan Modernisme, though Regoyos's path was distinct from theirs.

Within Spain, his relationship with his teacher Carlos de Haes was foundational. While he was a contemporary of prominent Spanish painters like Joaquín Sorolla and Ignacio Zuloaga, Regoyos's artistic concerns and international orientation set him apart. Sorolla was celebrated for his luminous beach scenes and portraits, capturing a vibrant, optimistic vision of Spain. Zuloaga, while also depicting a more "Spanish" Spain, often focused on dramatic, folkloric, or Goya-esque themes. Regoyos offered a different perspective, more aligned with European Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and often more critical or introspective in his portrayal of his homeland. He also maintained connections with Basque artists like Manuel Losada, contributing to the artistic ferment in that region.

Legacy and Influence

Darío de Regoyos's legacy is that of a pioneer. He was one of the first Spanish artists to fully embrace and adapt Impressionist and Pointillist techniques, and a crucial link between Spanish art and the European avant-garde. While his recognition in Spain was slow to come, his importance is now widely acknowledged. He is seen as a key figure in the modernization of Spanish painting, moving it away from academicism and towards a more subjective and light-filled interpretation of reality.

His "España Negra" series remains a powerful and unique contribution, offering a critical counterpoint to more idealized visions of Spain and prefiguring some of the social concerns that would later be explored by artists of the Generation of '98 and beyond. His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Spanish landscape painters, particularly in the Basque Country, where his work helped to foster a regional school of modern art.

Exhibitions of his work, such as the major retrospective held at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum in 2014-2015, have helped to solidify his reputation and introduce his art to a wider audience. He is no longer seen as a peripheral figure but as an essential artist who brought a modern European sensibility to Spanish art while remaining deeply engaged with the character and complexities of his native land. His dedication to capturing the truth of his perceptions, whether of light, landscape, or social reality, marks him as an artist of profound integrity and lasting significance. His work continues to resonate for its beauty, its honesty, and its unique vision of Spain at a crucial moment of transition.