Paul Signac stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A painter, theorist, and tireless promoter of avant-garde ideas, he was instrumental, alongside Georges Seurat, in developing the revolutionary technique of Pointillism and establishing Neo-Impressionism as a significant artistic movement. His vibrant canvases, often depicting sun-drenched harbors and shimmering waterways, are celebrated for their meticulous technique, luminous color, and harmonious compositions. Born in Paris on November 11, 1863, and passing away in the same city on August 15, 1935, Signac's life spanned a period of immense artistic change, a transformation he actively shaped.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Paul Signac was born into a prosperous Parisian family of shopkeepers. His father owned a successful saddlery business, providing a comfortable upbringing that allowed the young Signac a degree of freedom in pursuing his interests. Initially, his path seemed set towards architecture, a field he began studying. However, a formative experience in 1880 altered his trajectory irrevocably. A visit to an exhibition featuring the works of Claude Monet ignited a passion for painting, compelling him to abandon his architectural studies and dedicate himself entirely to art.

The early years of Signac's artistic development were deeply influenced by the Impressionists. He absorbed the lessons of painters like Monet and Auguste Renoir, admiring their commitment to capturing fleeting moments of light and color directly from nature. He frequented Impressionist circles, engaging with their ideas and techniques. This initial grounding in Impressionism provided a crucial foundation, but Signac's inquisitive mind and scientific inclination soon led him towards a more structured and analytical approach to painting.

The Meeting with Seurat and the Birth of Neo-Impressionism

A crucial turning point occurred in 1884 when Paul Signac met Georges Seurat. This encounter took place at the formation meetings of the Groupe des Artistes Indépendants, an organization they co-founded as an alternative to the official Salon, offering artists a place to exhibit freely without jury selection. Signac was immediately drawn to Seurat's systematic working methods and his innovative ideas about color theory, which were crystallizing into a new style that would become known as Divisionism or Pointillism.

Seurat was deeply engaged with contemporary scientific theories of optics and color perception, particularly the work of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. These theories explored concepts like simultaneous contrast (how adjacent colors influence each other) and optical mixing (how the eye blends small dots of distinct colors placed side-by-side). Seurat sought to apply these principles scientifically to painting, believing it could achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional color mixing on the palette.

Signac became Seurat's staunchest ally and collaborator. Together, they championed this new approach, which involved applying small, distinct dots or dabs of pure color directly onto the canvas. They believed that by juxtaposing complementary colors (like red and green, or blue and orange), they could intensify the visual sensation. The intention was for the viewer's eye to perform the "mixing" of these colors optically, resulting in a more brilliant and harmonious effect than could be achieved by physically blending pigments. This marked a significant departure from the more intuitive and spontaneous brushwork of the Impressionists.

The Principles of Pointillism and Divisionism

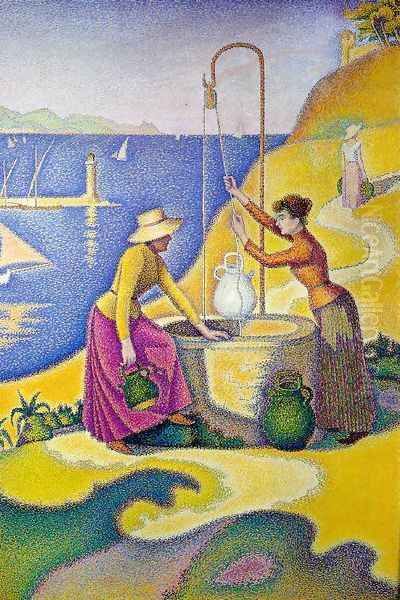

The technique meticulously developed by Seurat and Signac, often called Pointillism due to the characteristic dots, was more accurately termed Divisionism by the artists themselves, emphasizing the core principle of separating color into its constituent parts. Instead of mixing green on a palette, for instance, a Divisionist painter would apply small dots of blue and yellow next to each other, allowing the viewer's eye to fuse them into green at a distance.

This method aimed to maximize color intensity and luminosity. Signac argued passionately that mixing colors on the palette inevitably led to duller, "muddy" results. Optical mixing, he believed, preserved the purity and brilliance of individual pigments, creating a vibrant, shimmering surface that accurately captured the effects of intense light. The application of paint was precise and controlled, a stark contrast to the rapid, gestural brushstrokes often employed by Impressionists like Monet or Renoir.

While Seurat's application often involved very fine, uniform dots, Signac's approach evolved over time. He sometimes employed slightly larger, squarer brushstrokes, resembling mosaic tiles (tesserae). This variation still adhered to the principles of optical mixing but could create different textural effects and a bolder visual rhythm. The goal remained the same: to build form and represent light through the scientific juxtaposition of pure color.

Signac as Theorist and Promoter

Georges Seurat's tragically early death in 1891 left Signac as the de facto leader and chief spokesperson for the Neo-Impressionist movement. He took on this role with energy and conviction, becoming a tireless advocate for Divisionist principles. He was not only a practitioner but also a crucial theorist, articulating the ideas behind the movement in writing and lectures.

His most significant theoretical contribution was the book D'Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme (From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism), published in 1899. In this influential text, Signac traced the historical lineage of their color theories, arguing that Neo-Impressionism was the logical culmination of earlier developments, particularly citing the color practices of the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. He presented Divisionism not as a radical break, but as a scientifically informed evolution of color usage in painting, providing a theoretical framework and justification for the movement.

Signac also played a vital role in organizing exhibitions and fostering a community around Neo-Impressionism. He remained a key figure in the Société des Artistes Indépendants, serving as its president from 1908 until his death. This position allowed him to ensure that emerging avant-garde artists had a venue to show their work. He actively encouraged younger painters, sharing his knowledge and promoting the Divisionist technique. Artists like Henri-Edmond Cross and Maximilien Luce became important figures within the Neo-Impressionist circle, influenced by both Seurat and Signac. Even Camille Pissarro briefly adopted the technique before finding it too restrictive.

Subject Matter: Light, Water, and Ports

While Seurat often focused on scenes of Parisian leisure and monumental figure compositions, Signac developed a particular affinity for landscapes and seascapes. He was captivated by the play of light on water and the vibrant atmosphere of coastal towns. His passion for sailing provided him with endless subject matter.

He frequently depicted the ports and coastlines of France, particularly the Mediterranean South. Saint-Tropez, which he "discovered" in 1892 while sailing, became a favorite motif, appearing in numerous canvases bathed in the brilliant southern light. He painted the harbors of Marseille, Antibes, and Collioure, as well as locations along the Atlantic coast like Brest and Saint-Malo. His travels also took him further afield, leading to series of paintings featuring Venice, Rotterdam, and Constantinople (Istanbul).

Water, with its constantly shifting reflections and capacity to fracture light into myriad colors, was an ideal subject for the Divisionist technique. Signac excelled at capturing the dazzling effects of sunlight on the sea, the colorful sails of fishing boats, and the architectural forms of harbors under different atmospheric conditions. His paintings are celebrations of light, color, and the ordered beauty he perceived in these maritime scenes.

Analysis of Key Works

Signac's extensive oeuvre includes several landmark paintings that exemplify his style and concerns:

The Dining Room, Opus 152 (1886-1887): An early major work created while Seurat was still alive, this interior scene demonstrates the application of Divisionist principles to a domestic setting. It depicts a family meal, rendered with meticulous dots of color. The stiffness of the figures and the highly structured composition reflect the rigorous nature of the technique in its early phase. It explores the effects of artificial light mixed with daylight.

Snow, Boulevard de Clichy, Paris (1886): Painted in the same year as Seurat's masterpiece A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, this work shows Signac applying the Pointillist technique to an urban landscape. He captures the specific light of a snowy day in Paris, using divided touches of blues, whites, pinks, and yellows to render the snow-covered street and bare trees, demonstrating the technique's versatility beyond sunny climes.

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890: This iconic portrait depicts the art critic and anarchist Félix Fénéon, a key supporter of Neo-Impressionism. The highly stylized composition features Fénéon in profile against an abstract, swirling background of vibrant colors and patterns, supposedly inspired by Japanese prints and psychedelic aesthetics. The title itself emphasizes the formal and musical qualities Signac sought in his art.

The Port of Saint-Tropez (various versions, e.g., 1899, 1901): Signac painted the port of Saint-Tropez numerous times. These works often feature a dynamic composition with sailboats, calm water reflecting the brightly colored buildings and sky, and the distinctive town architecture. They showcase his mature style, often using slightly larger, mosaic-like brushstrokes, capturing the intense luminosity of the Mediterranean with a vibrant palette.

The Papal Palace, Avignon (1900): This painting is characteristic of Signac's mature period, depicting the imposing historical architecture of the Papal Palace. He uses Divisionism to break down the solid forms into shimmering surfaces of light and color, juxtaposing warm oranges and yellows with cool blues and violets to create a sense of vibration and atmospheric depth. The structured composition contrasts with the dazzling color effects.

Evolution of Style

While remaining committed to the core principles of Divisionism throughout his career, Signac's style was not static. In his early works, closely aligned with Seurat, the application of dots was often fine and meticulous. Following Seurat's death, and particularly from the mid-1890s onwards, Signac's touch became broader and more expressive.

He began using larger, squarer, or rectangular brushstrokes, resembling mosaic tesserae. This evolution allowed for greater dynamism and vibrancy in his canvases. The colors often became even bolder and more intense, moving away from strict naturalism towards a more heightened, expressive use of color. This later style, while still based on optical mixing, possessed a greater sense of freedom and decorative rhythm.

Signac was also a prolific watercolorist and produced etchings and lithographs. His watercolors, often executed during his travels, possess a remarkable freshness and spontaneity. He used transparent washes of bright color, often leaving areas of white paper exposed, achieving a luminous effect that complemented his oil painting technique. These works on paper reveal a more fluid aspect of his artistic practice.

The Sailor and Traveler

Signac's passion for sailing was inextricably linked to his art. He was an avid yachtsman, owning a succession of boats throughout his life, famously including one named Olympia. Sailing provided him not only with leisure and adventure but also with direct access to the subjects he loved most: water, light, and coastal scenery.

He navigated the coasts of Brittany, Normandy, and especially the Mediterranean. His logbooks and sketches document these journeys extensively. Discovering Saint-Tropez by boat in 1892 was a pivotal moment; he bought a house there (La Hune) and spent much of his time painting in the region. His travels extended beyond France, taking him to Holland, Venice, and Constantinople, each location inspiring series of paintings where he applied his Divisionist technique to new motifs and light conditions. This constant engagement with different environments refreshed his vision and provided a continuous stream of inspiration.

His paintings often convey a deep affection for the maritime world – the bustling activity of ports, the elegant forms of sailboats, the vastness of the sea, and the changing moods of the sky. His firsthand experience as a sailor lent authenticity and intimacy to these depictions.

Political Beliefs and Social Conscience

Beyond his artistic pursuits, Paul Signac held strong political convictions. He was a committed anarchist, aligning himself with the libertarian ideals prevalent in certain artistic and literary circles of the time. He counted fellow anarchists like the critic Félix Fénéon among his close associates and contributed illustrations to anarchist publications like Les Temps Nouveaux (The New Times).

While his paintings rarely depicted overt political themes, his anarchist beliefs arguably informed his artistic vision. Some interpretations suggest that the harmonious, ordered, and light-filled landscapes he created represented a kind of utopian ideal – a vision of a world free from conflict and oppression, bathed in the clarifying light of reason and nature. His dedication to the independent, jury-free Salon des Indépendants can also be seen as consistent with his anti-authoritarian principles, promoting artistic freedom and equality. He was known to be actively opposed to anti-Semitism and injustice, reflecting a broader humanitarian concern within his political outlook.

Influence and Legacy

Paul Signac's impact on the course of modern art was significant and multifaceted. As the primary champion of Neo-Impressionism after Seurat, he ensured the movement's continuation and dissemination. His theoretical writings, particularly From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism, provided a crucial intellectual framework that influenced subsequent generations.

His emphasis on pure, expressive color had a profound effect on younger artists searching for new directions beyond Impressionism. Most notably, Henri Matisse and André Derain were directly inspired by Signac's work. Matisse's painting Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904), created after spending time with Signac in Saint-Tropez, is a key example of Divisionism influencing the nascent Fauvist movement. While the Fauves ultimately abandoned the systematic dot technique in favor of broader, more impulsive brushstrokes, Signac's liberation of color was a critical catalyst for their development.

Signac's influence extended beyond France. His work impacted the Italian Futurists, such as Gino Severini and Umberto Boccioni, who adapted Divisionist techniques to depict dynamism and modern life. Early abstract painters, including Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian during his early figurative phases, also absorbed lessons from Neo-Impressionism's approach to color and structure. Even Vincent van Gogh, during his time in Paris, interacted with Signac and experimented briefly with Pointillist ideas, visible in some of his works from that period. Alongside contemporaries like Paul Gauguin, who pursued different paths away from Impressionism, Signac played a vital role in opening up new possibilities for painting at the turn of the century.

Conclusion

Paul Signac remains a major figure in art history, celebrated for his dual role as a pioneering painter and an influential theorist. His collaboration with Georges Seurat resulted in the revolutionary technique of Pointillism, which fundamentally altered approaches to color and light in painting. As the leading proponent of Neo-Impressionism for over four decades, he tirelessly advocated for its principles through his art, writings, and organizational activities.

His luminous depictions of French harbors and waterways, rendered with vibrant, scientifically applied color, continue to captivate viewers with their harmony and brilliance. Beyond his technical innovations, Signac's passion for sailing, his engagement with political ideas, and his crucial influence on subsequent movements like Fauvism solidify his legacy. He stands as a testament to the productive fusion of artistic sensitivity, intellectual rigor, and a profound connection to the natural world, leaving behind an oeuvre that radiates light and color.