Introduction: Bridging East and West

Gyula Tornai stands as a significant figure in Hungarian art history, renowned primarily for his captivating contributions to the Orientalist genre. Born in 1861 and passing in 1928, Tornai's life and work were characterized by a deep fascination with cultures far removed from his native Hungary. He translated his extensive travels across North Africa and Asia into vibrant, detailed canvases that captured the European imagination during a period of intense interest in the "exotic" East. His meticulous technique, combined with a keen eye for cultural detail and atmosphere, established him as a leading Orientalist painter of his time, whose works continue to be admired for their artistry and historical insight.

Tornai was not merely an observer but an active participant in the cultural exchange between Europe and the East. His journeys provided him with firsthand experiences that infused his paintings with a sense of authenticity, depicting bustling marketplaces, serene interiors, intimate moments of daily life, and portraits of individuals encountered on his travels. He moved beyond simple exoticism, often exploring the nuances of cultural practices, social structures, and artistic traditions he witnessed, particularly during his extended stay in Japan. His legacy is that of an artist who skillfully navigated different worlds, bringing the richness of the Orient to European audiences through a distinctly Hungarian artistic lens.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gyula Tornai was born in Göröge, Hungary, in 1861. His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training at some of the most prestigious art centers in Europe. He honed his skills initially in Vienna and later at the Munich Academy, both crucial hubs for artistic education in the late 19th century. These institutions provided him with a strong foundation in academic drawing and painting techniques, emphasizing realism, anatomical accuracy, and compositional structure, which would underpin his later, more exotic works.

His education culminated in Budapest, where he studied under the tutelage of Gyula Benczúr (1844-1920). Benczúr was a highly respected Hungarian painter, known for his historical scenes and portraits executed in a grand academic style. Studying in Benczúr's master studio provided Tornai with invaluable guidance and likely reinforced his commitment to technical proficiency and detailed representation. This rigorous academic background equipped Tornai with the necessary skills to tackle complex compositions and render intricate details, qualities that would become hallmarks of his Orientalist paintings.

The Call of the Orient: Travels and Inspirations

The prevailing European fascination with the East, often termed Orientalism, deeply influenced Tornai's artistic direction. Seeking inspiration beyond the confines of European studios and subjects, he embarked on extensive travels that would define his career. His journeys took him far from Hungary, immersing him in the cultures, landscapes, and daily rhythms of life in North Africa and Asia. These experiences were not fleeting tourist trips but often involved extended stays, allowing for deeper engagement and observation.

One of his significant early destinations was Morocco. He spent considerable time in Tangier between 1890 and 1891, a city that had already attracted numerous European and American artists, including the French master Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) decades earlier. Tangier, with its vibrant mix of cultures, bustling souks, distinctive architecture, and intense light, provided a wealth of subject matter. Tornai produced numerous works during this period, capturing the essence of Moroccan life, from street scenes and merchant activities to intimate interior views, demonstrating his burgeoning skill in depicting non-European settings.

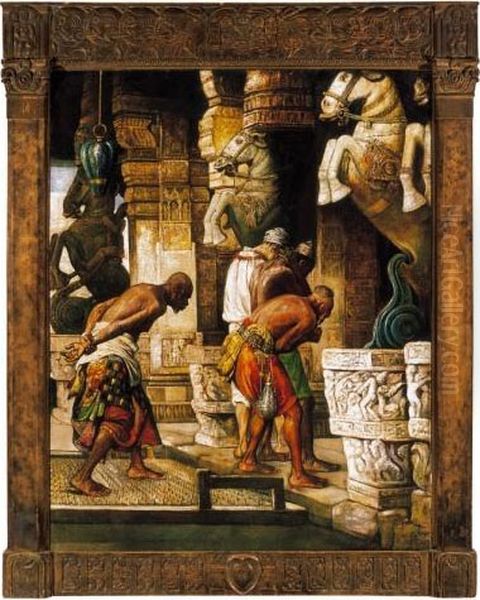

His wanderlust did not end in North Africa. Tornai's travels extended further east, taking him to the vast and diverse landscapes of India and eventually to the Far East, including China and, most significantly, Japan. Each destination offered new visual stimuli, cultural practices, and artistic traditions that enriched his palette and thematic repertoire. He collected artifacts, observed customs, and sketched prolifically, gathering the raw material that would later be transformed into elaborate studio paintings upon his return to Europe or during extended stays abroad.

Focus on Japan: Residence and Cultural Exchange

Tornai's engagement with Japan was particularly profound and marks a distinct phase in his career. He lived in Japan for an extended period, reportedly around 1904-1905, although sources sometimes vary slightly on the exact duration, suggesting a stay of up to six years encompassing this timeframe. This was not merely a visit but an immersion. He travelled throughout the country, absorbing its unique aesthetics, traditions, and social fabric during the Meiji era, a time when Japan itself was undergoing rapid modernization while striving to maintain its cultural identity.

His time in Japan yielded a significant body of work focused specifically on Japanese themes. He painted scenes depicting traditional customs, such as dancers in elaborate kimonos, serene temple gardens, and glimpses of everyday life. These works often showcased his ability to adapt his style to capture the different light, colour palette, and decorative sensibilities of Japanese culture. He seemed particularly interested in traditional arts and performances, reflecting the broader European interest in Japonisme.

Beyond painting, Tornai actively engaged with Japanese cultural circles. Evidence suggests interactions with figures like Wadagaki Kenzō (1860-1919), a prominent scholar, translator, and poet associated with Tokyo Imperial University. While perhaps not a direct artistic collaborator in the studio sense, such connections indicate Tornai's integration into the intellectual and cultural life of Japan. He reportedly participated in gatherings of artists, such as those organized by a group referred to as "Tomoe-kai," suggesting involvement with contemporary Japanese art movements or circles interested in cultural exchange.

A notable outcome of his time in Japan was the creation of a portrait of Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838-1922), a highly influential figure who served twice as Prime Minister of Japan. This portrait, now housed in the Aizu Museum of Waseda University (an institution founded by Ōkuma), is a testament to Tornai's access to prominent figures and his role as a cultural conduit. The painting itself provides a valuable visual record of this important historical personality, rendered through the lens of a European academic painter.

Tornai's Japanese works were exhibited not only in Japan but also back in Europe, particularly in Budapest. In 1909, he held a significant exhibition at the Budapest Art Gallery (Műcsarnok), showcasing paintings created during his travels in India and Japan. These exhibitions played a crucial role in introducing authentic (or at least firsthand-observed) depictions of Japanese life and aesthetics to Hungarian audiences, contributing to the wave of Japonisme influencing European art and design at the time. Artists like James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and James Tissot (1836-1902) had already popularized Japanese aesthetics in Britain and France, and Tornai contributed to this trend from a Central European perspective.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Gyula Tornai's artistic style is firmly rooted in the academic realism he absorbed during his training, but it is animated by the exotic subject matter he pursued. His approach aligns closely with the mainstream of late 19th and early 20th-century Orientalist painting, characterized by meticulous attention to detail, a rich colour palette, and a focus on narrative or atmospheric scenes set in North African or Asian locales. He shared this detailed, often ethnographic approach with contemporaries like Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854-1932), Austrian painters known for their highly finished depictions of Middle Eastern life.

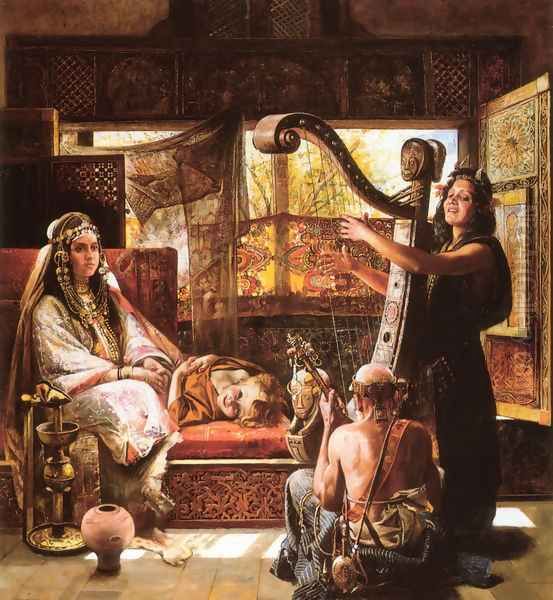

A key feature of Tornai's work is his skillful rendering of textures and surfaces – the intricate patterns of carpets and textiles, the gleam of metalwork, the rough texture of stone walls, the delicate translucency of porcelain, or the richness of silk garments. This tactile quality adds to the immersive experience of his paintings, inviting the viewer into the depicted scene. His compositions are often complex, featuring multiple figures engaged in various activities within detailed architectural settings, whether a bustling bazaar, a quiet courtyard, or an opulent interior.

His use of colour is vibrant and evocative, capturing the intense light of North Africa or the more subtle, harmonious palettes associated with Japanese aesthetics. He masterfully handled light and shadow to create depth, define form, and enhance the mood of his paintings, whether conveying the heat of a desert afternoon or the cool tranquility of a shaded interior. While grounded in realism, his works often possess a romanticized quality, reflecting the European fascination with the perceived sensuality, mystery, and timelessness of the East.

Thematically, Tornai explored a wide range of Orientalist subjects. He painted scenes of commerce (merchants, markets), leisure (musicians, dancers, smokers), domestic life (harems, family gatherings), religious practices, and scholarly pursuits (scholars examining artifacts). Figures like traders, musicians, guards, scholars, and women in traditional attire populate his canvases. His depictions of harem scenes or odalisques align with common Orientalist tropes, though his firsthand travel experience potentially lent a greater degree of observed detail compared to artists who relied solely on imagination or studio props, like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) sometimes did.

His Japanese works, while still detailed, sometimes show a subtle shift, incorporating elements of Japanese compositional strategies, such as flattened perspectives or decorative patterning, reflecting the influence of Japonisme that also impacted artists like Edgar Degas (1834-1917) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). He depicted specific Japanese cultural elements like temples, traditional clothing, festivals, and art forms, showcasing his direct observation during his residency.

Key Works and Masterpieces

Several paintings stand out as representative of Gyula Tornai's oeuvre and his contribution to Orientalism. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be complex due to works dispersed in private collections, certain titles frequently appear in auction records and art historical discussions.

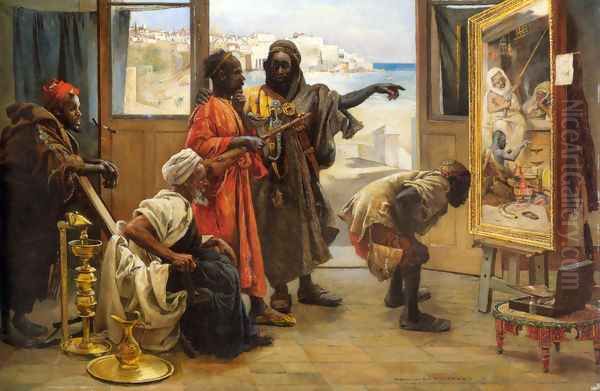

_The Connoisseurs_ (also known as _Les Connaisseurs_ or _A Műértők_): This is perhaps one of Tornai's most frequently cited works. Typically depicting a group of learned men or wealthy merchants gathered in a richly decorated interior, examining artifacts like pottery, weapons, or textiles. These scenes allowed Tornai to showcase his skill in rendering diverse textures, intricate details of costume and architecture, and the focused expressions of the figures, creating a narrative of appreciation and cultural richness.

_Oriental Scene_: This title likely encompasses several works depicting various aspects of life in North Africa or the Middle East. These could range from bustling market squares filled with vendors and shoppers to quieter moments in courtyards or mosques. Such paintings emphasize atmosphere, local colour, and the daily activities of the people, rendered with Tornai's characteristic detail.

_The Duet_: Often featuring musicians, perhaps in an intimate interior setting, playing traditional instruments. This theme allowed Tornai to explore cultural practices related to music and entertainment, while also providing opportunities to depict elaborate costumes and decorative settings. The focus is often on the concentration of the performers and the implied sound and atmosphere.

_The Dance of Salome_: This subject, drawn from biblical narrative but often given an Orientalist flavour, was popular among European artists in the late 19th century. Tornai's interpretation likely featured the dramatic dance within an opulent, imagined Eastern court setting, allowing for the depiction of exotic costumes, movement, and sensuality, themes common in Orientalist art exploring female figures.

Japanese Subjects (e.g., _Geishas_, _Temple Scenes_, _Portrait of Ōkuma Shigenobu_): His works from Japan form a distinct and important category. Paintings of geishas or dancers capture the elegance of traditional Japanese attire and performance. His landscapes or temple scenes reflect the unique aesthetics of Japanese architecture and gardens. The aforementioned portrait of Ōkuma Shigenobu is significant both artistically and historically.

These works collectively demonstrate Tornai's range within the Orientalist genre, his technical mastery, his dedication to capturing cultural details (as he perceived them), and his ability to create compelling, atmospheric scenes that appealed strongly to European tastes of the era.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

Gyula Tornai achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, both within Hungary and internationally. His participation in major exhibitions was key to building his reputation. He regularly showed his work at the Budapest Art Gallery (Műcsarnok) and the National Salon (Nemzeti Szalon), the premier venues for contemporary art in Hungary at the time. His exhibitions in 1909 and 1917, featuring works from his travels, were significant events.

Internationally, his presence was marked by his participation in exhibitions in prominent European art centers like Paris and London. A major milestone was receiving a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1900. This award conferred significant international prestige and validated his status as a painter of note on the European stage, placing him alongside numerous other artists vying for recognition at this massive cultural event.

His works were acquired by museums and private collectors, ensuring their preservation and continued visibility. Today, his paintings can be found in the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and other public and private collections across Europe and potentially beyond. His works continue to appear at international art auctions, often commanding high prices, indicating sustained interest from collectors of Orientalist art.

Tornai's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to Hungarian Orientalism. He was one of the foremost Hungarian painters to dedicate a significant portion of his career to depicting Eastern subjects based on extensive firsthand travel. His detailed, academic style provided European audiences with vivid, albeit sometimes romanticized, glimpses into cultures that seemed distant and fascinating. His Japanese works are particularly important, documenting his deep engagement with Japanese culture and contributing to the Japonisme phenomenon in Central Europe. He remains a key figure for understanding the intersection of Hungarian art, academic realism, and the global phenomenon of Orientalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tornai in Context: Orientalism and Contemporaries

Gyula Tornai operated within a well-established European tradition of Orientalist painting. This genre, popularized earlier in the 19th century by artists like Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), reached its peak in the latter half of the century with painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), Ludwig Deutsch, and Rudolf Ernst. Tornai shared with these artists a focus on detailed realism, ethnographic accuracy (or the appearance thereof), and themes drawn from North African, Middle Eastern, and sometimes Asian life. His work fits comfortably within this broader movement, reflecting its fascination with exoticism, sensuality, and the perceived otherness of non-European cultures.

Within the Hungarian context, Tornai stands out for his specific focus on Orientalist themes based on extensive travel. While other Hungarian artists achieved greater fame for different subjects – such as Mihály Munkácsy (1844-1900) for his dramatic realism and large-scale historical scenes, or Pál Szinyei Merse (1845-1920) for his pioneering plein-air landscapes – Tornai carved a distinct niche. His work can also be seen in relation to Hungarian academic painting, represented by his teacher Gyula Benczúr, and perhaps contrasted with emerging modernist trends, like the Nagybánya school led by artists such as Károly Ferenczy (1862-1917), which emphasized plein-air painting and more impressionistic or post-impressionistic styles.

His connection to Japonisme places him in dialogue with a wide array of European artists influenced by Japanese art, including Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, as well as figures associated with Aestheticism like Whistler. While Tornai's engagement might have been more thematic and observational than the stylistic borrowing seen in some French avant-garde circles, his Japanese works and their exhibition in Europe contributed to this cross-cultural artistic current.

The mention of Gyula Éder (1875-1945) in some sources, perhaps in the context of Hungarian Symbolism or thematic contrasts, suggests Tornai's work was also viewed alongside other contemporary Hungarian artistic developments, even if his primary alignment was with international Orientalism and academic realism. His career spanned a period of significant artistic change, from the dominance of academicism to the rise of modernism, and his work reflects the enduring appeal of detailed representation and exotic subject matter during this transition.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the East

Gyula Tornai remains a compelling figure in the history of Hungarian and European art. As a master of the Orientalist genre, he dedicated his considerable technical skill, honed through rigorous academic training under figures like Gyula Benczúr, to capturing the essence of the distant lands he explored. His extensive travels across North Africa, India, China, and particularly his immersive experience in Japan, provided the foundation for a body of work rich in detail, atmosphere, and cultural observation.

His paintings, from bustling Moroccan markets and intimate Egyptian interiors to serene Japanese temples and portraits of dignitaries like Ōkuma Shigenobu, offered European audiences a window into worlds perceived as exotic and alluring. While viewed today through the critical lens of Orientalism's complex history, Tornai's works endure as testaments to his artistic talent, his adventurous spirit, and the profound cultural encounters that shaped his vision. Recognized with awards like the Paris Exposition medal and exhibited widely, his art bridged geographical and cultural divides, leaving a significant legacy within the tradition of academic realism and the captivating allure of the East in Western art.