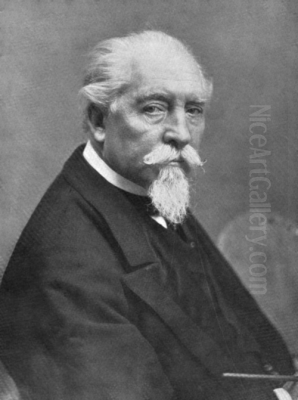

Introduction: A Victorian Visionary

Frederick Goodall RA (Royal Academician) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. Born in London on March 17, 1822, and passing away in the same city on July 29, 1904, his long and prolific career spanned a period of immense change, both in the art world and society at large. Initially celebrated for his charming depictions of British rural life and historical scenes, Goodall is perhaps best remembered today for his later, extensive body of work dedicated to Orientalist themes, particularly scenes of Egyptian life, often imbued with biblical resonance. His journey from the fields of England and Normandy to the deserts and waterways of Egypt reflects a broader Victorian fascination with the East, yet Goodall brought his own distinct vision and meticulous approach to these subjects, earning him considerable fame and recognition during his lifetime.

He hailed from an artistic family, which undoubtedly shaped his path. His father was the renowned steel line engraver Edward Goodall (1795–1870), celebrated for his skillful interpretations of works by masters such as J.M.W. Turner. This familial connection to the arts provided Frederick with an environment steeped in visual culture from a young age, fostering his innate talent and setting the stage for a career dedicated to painting. His brothers, Edward Angelo Goodall and Walter Goodall, also pursued artistic careers, making the Goodalls a notable family within the London art scene. Frederick's early immersion in this world, combined with his natural abilities, allowed him to develop rapidly as an artist.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Frederick Goodall received his initial art education within his family circle and later honed his skills, demonstrating promise from a remarkably early age. Encouraged by his father, he began sketching and painting scenes from life around him. His formal debut into the competitive London art world came swiftly. At the tender age of just sixteen, in 1838, he exhibited his first oil painting at the prestigious Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. This early acceptance was a significant achievement, marking the beginning of a long association with the institution that would become central to his career.

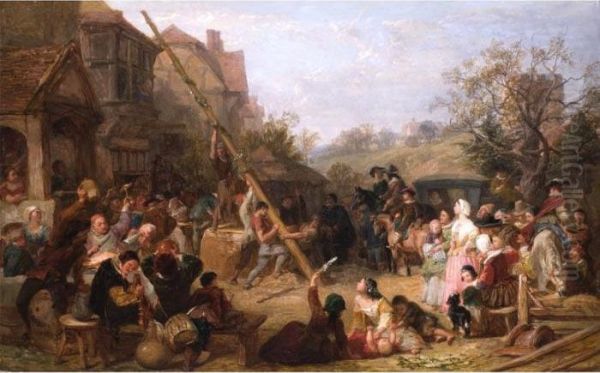

His early works primarily focused on subjects closer to home, drawing inspiration from the British countryside, its inhabitants, and moments from national history. These paintings often reflected the prevailing tastes of the time, favouring narrative clarity, sentimental appeal, and detailed observation. To gather material and broaden his artistic horizons, Goodall undertook numerous sketching trips between 1838 and 1857. His travels took him across the British Isles – to Wales, Ireland, and Scotland – as well as across the Channel to Normandy and Brittany in France, and further afield to Venice. These journeys provided a wealth of subjects, from rustic village festivals and agricultural scenes to coastal landscapes and historical vignettes.

During this formative period, Goodall began to establish his reputation. One notable early success was The Tired Soldier, Resting at a Roadside Well, exhibited in 1842, which won a prize from the British Institution. Other significant works from this era include The Village Festival (1847, now in the Tate collection) and Raising the Maypole (1851), which showcase his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and capture the spirit of traditional English life. These paintings demonstrated his technical proficiency and his growing popularity with the public and critics alike, laying a solid foundation for his future career. His skill was recognized formally when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1852.

The Call of the East: The First Egyptian Journey

A pivotal moment in Frederick Goodall's artistic development occurred in the winter of 1858. Seeking new inspiration and drawn by the growing European fascination with the 'Orient', he embarked on his first journey to Egypt. This was a significant undertaking, reflecting a desire to move beyond the familiar landscapes of Britain and Europe and engage with a culture and environment that seemed both ancient and exotic to the Victorian imagination. He did not travel alone; his companion on this formative trip was the German-born painter Carl Haag (1820–1915), who himself became a noted Orientalist artist, particularly skilled in watercolour.

The months spent in Egypt during 1858-1859 had a profound and lasting impact on Goodall's art. He was captivated by the quality of the light, the vibrant street life of Cairo, the majestic ruins of ancient civilizations along the Nile, and the distinct customs and attire of the people. He immersed himself in this new environment, sketching prolifically and gathering materials that would fuel his paintings for years to come. While one of his stated aims was to find authentic settings for biblical subjects, the everyday life he witnessed proved equally compelling. The experience fundamentally shifted his artistic focus.

Upon his return to London, Goodall began translating his sketches and experiences onto canvas. The public and critics quickly responded to his new subject matter. One of the first major works resulting from this trip was Early Morning in the Wilderness of Shur (1860). Exhibited at the Royal Academy, this painting depicted Hagar and Ishmael, a biblical scene set against a meticulously rendered desert landscape informed by his direct observations. The painting was highly praised for its atmospheric quality and its convincing portrayal of the Near Eastern setting, signaling the successful launch of the Egyptian phase of his career. This journey marked a definitive turn, moving him firmly into the ranks of prominent British Orientalist painters.

Master of Orientalism: Themes and Style

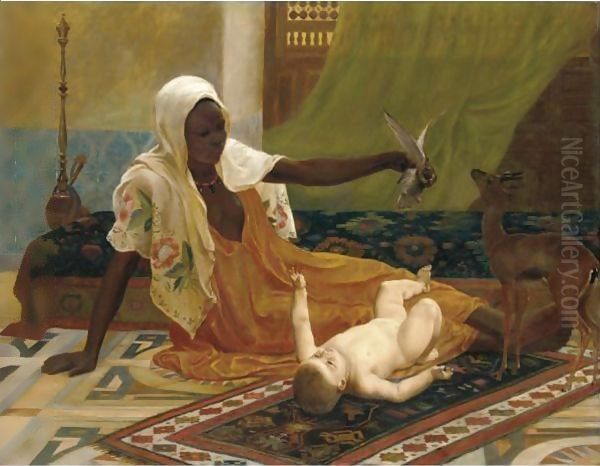

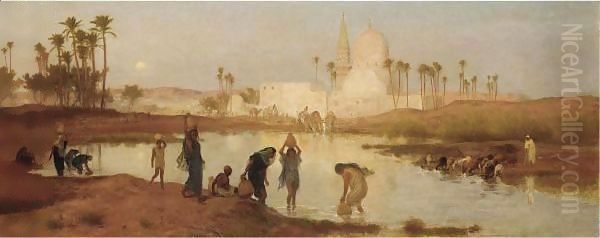

Following his transformative first visit to Egypt, Frederick Goodall dedicated a significant portion of his career to Orientalist subjects. His paintings from this period encompass a range of themes, including evocative Nile landscapes, detailed scenes of daily life in villages and markets, depictions of Bedouin encampments in the desert, intimate domestic interiors, and, notably, historical and biblical narratives reimagined within authentic Egyptian settings. He drew heavily upon the sketches, studies, and artifacts – such as costumes and props – that he had meticulously collected during his travels, lending his works an air of ethnographic accuracy that appealed greatly to Victorian audiences.

Goodall's style in his Orientalist works is characterized by careful draughtsmanship, a rich and often luminous colour palette, and a commitment to detailed rendering, particularly in fabrics, architecture, and human figures. While striving for a sense of realism based on his observations, his paintings are often imbued with a romantic sensibility. They present an idealized vision of Egypt, emphasizing its picturesque qualities, ancient mystique, and the perceived timelessness of its traditional ways of life. This blend of detailed observation and romantic idealization was typical of much 19th-century Orientalist art.

His approach placed him firmly within the broader European Orientalist movement, alongside artists like the French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), known for his highly finished scenes of Middle Eastern life, and fellow British artists such as John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), who lived in Cairo for a decade and produced intricate watercolours and oils of domestic scenes. Goodall's work also resonates with the earlier topographical and architectural studies of Egypt and the Near East by the Scottish painter David Roberts (1796–1864), whose lithographs had widely popularized these landscapes. Goodall, however, focused more on the human element and narrative potential of Egyptian settings, particularly their connection to biblical history.

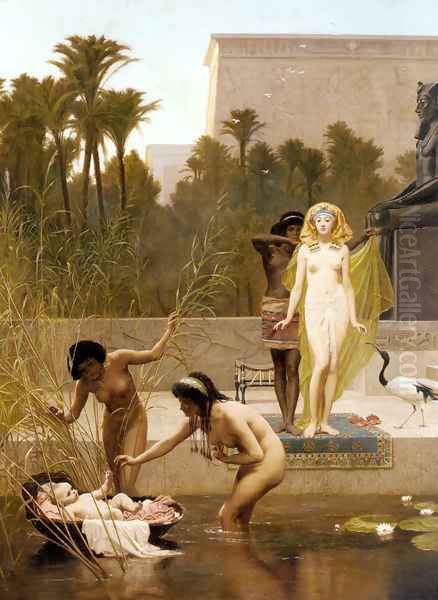

Biblical Narratives Reimagined

A distinctive feature of Frederick Goodall's Orientalist oeuvre was his dedication to depicting biblical scenes within historically and geographically plausible Egyptian contexts. This practice, sometimes referred to as 'Biblical Orientalism', sought to bring the stories of the Old and New Testaments to life by grounding them in the landscapes, architecture, and cultures of the Holy Land and neighbouring regions, as observed (or imagined) by 19th-century artists. Goodall became one of the foremost British proponents of this genre, using his Egyptian experiences to lend an air of authenticity to his religious paintings.

His Finding of Moses, painted in several versions, is a prime example. Set against a lush Nile backdrop, it portrays the biblical event with Egyptian figures in contemporary (19th-century) local dress, effectively merging the ancient narrative with his modern observations. Similarly, Early Morning in the Wilderness of Shur (1860) placed Hagar and Ishmael in a desert landscape that reflected his direct studies. These works aimed to make the Bible stories more immediate and relatable to a Victorian audience increasingly interested in historical accuracy and archaeological discovery.

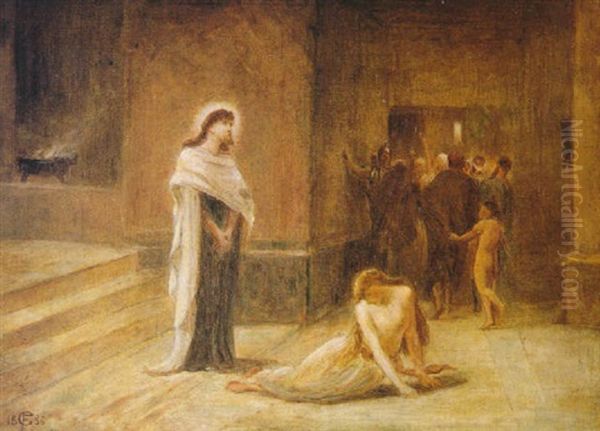

Perhaps one of his most discussed later works in this vein was Misery and Mercy (sometimes cited as Miseries and Mercies), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1888 (reportedly painted in 1887). This large canvas depicted the New Testament story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery (John 8:1-11), focusing on the moment of forgiveness. Set in what appears to be the Temple courtyard, the painting features a diverse crowd rendered with Goodall's characteristic attention to detail in costume and physiognomy. Notably, as some contemporary sources pointed out, the work eschewed overt traditional religious symbolism, perhaps reflecting a broader 19th-century trend towards more humanized and historically contextualized depictions of Christ, as seen in works by artists like William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) in his The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple or the French painter James Tissot (1836-1902) in his extensive series on the life of Christ. Goodall's interpretation emphasized the human drama and the moral lesson of the story within a carefully constructed Orientalist setting.

Return to the Nile and Later Works

Goodall's fascination with Egypt drew him back for a second extended visit in 1870. This time, seeking an even deeper immersion, he spent several months living among Bedouin Arabs near Saqqara, close to the pyramids and the desert's edge. This experience provided him with intimate insights into nomadic life, customs, and the stark beauty of the desert environment. It further enriched his visual repertoire and allowed him to depict Bedouin subjects with greater familiarity and detail in his subsequent paintings.

The works produced after this second trip often reflect this deeper engagement. Paintings like The Subsiding of the Nile (1873), which shows villagers returning to their fields after the annual flood, or A New Light in the Harem (c. 1884, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), depicting a Cairene interior, showcase his continued dedication to Egyptian themes. He continued to explore various facets of Egyptian life, from agricultural cycles and water carriers at the river (The Water Carriers, 1877) to tranquil domestic scenes and depictions of traditional crafts and markets. His ability to capture the atmospheric effects of light, particularly the intense sunlight and long shadows of the Egyptian climate, remained a hallmark of his style.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Goodall remained highly productive, regularly exhibiting large-scale Egyptian subjects at the Royal Academy. Works such as The Time of the Overflow of the Nile (1875), Sheep Washing near the Pyramids of Gizeh (1876), and The Holy Mother (1885) continued to find favour with the public. He also painted portraits and continued occasionally to produce British subjects, but Egypt remained his dominant source of inspiration. The Palm Offering (1892), a late work, demonstrates his enduring commitment to these themes, depicting a religious procession with characteristic detail and compositional skill.

Academic Recognition and Exhibitions

Frederick Goodall's career was closely intertwined with the Royal Academy of Arts, the epicentre of the British art establishment in the 19th century. His election as an Associate (ARA) in 1852 was followed by his elevation to full Royal Academician (RA) status in 1863. This was a significant honour, confirming his position among the leading artists of his day. Membership provided prestige, exhibition opportunities, and a voice within the institution. Goodall remained a loyal and frequent contributor to the Academy's annual Summer Exhibition for most of his working life, exhibiting a total of over 170 works there between 1838 and 1904.

The RA Summer Exhibition was the most important event in the London art calendar, attracting vast crowds and considerable press attention. Success at the Academy could make an artist's reputation and secure lucrative sales and commissions. Goodall's Egyptian subjects proved particularly popular at these exhibitions, often praised for their exoticism, technical finish, and narrative interest. His large, ambitious canvases were frequently given prominent placement, ensuring visibility and critical discussion. He was part of a generation of highly successful Victorian Academicians, contemporaries who also enjoyed great public acclaim, such as Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), Edward Poynter (1836-1919), and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), known for their classical and historical subjects, some of which also incorporated elements of Eastern or archaeological detail.

Beyond the Royal Academy, Goodall sought international recognition. He exhibited works at the great Paris Exposition Universelle (World's Fairs) of 1867 and 1878. These major international exhibitions provided artists with a global stage to showcase their talents and compete for awards. Goodall's participation indicates his ambition and his established reputation beyond British shores. In 1869, he also held a significant exhibition of fifty oil sketches derived from his travels, showcasing the preparatory work behind his finished paintings and offering insight into his working methods. These various platforms solidified his status as a major figure in Victorian art.

The Artist and His Contemporaries

While detailed records of Frederick Goodall's day-to-day interactions with fellow artists are not abundant, his long career within the London art world placed him firmly within its social and professional networks. His most documented artistic relationship was with Carl Haag, his companion on the crucial first trip to Egypt. Their shared experience undoubtedly fostered artistic exchange, although their later careers saw Haag focus more on watercolour while Goodall primarily worked in oils. His connection to his father, Edward Goodall, and his engraver's relationship with J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) placed him, from the outset, in proximity to major figures, even if indirectly.

His Orientalist works inevitably invite comparison with other British artists exploring similar themes. John Frederick Lewis, who returned to London in 1851 after his long stay in Cairo, produced works of intricate detail that likely influenced Goodall, although Goodall often worked on a larger scale and tackled more narrative subjects. The influence of David Roberts' earlier topographical views of Egypt is also apparent, particularly in establishing a visual vocabulary for depicting the region's monuments and landscapes. Goodall's biblical Orientalism connects him to the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt, who also travelled to the Holy Land seeking authenticity for his religious works, though their styles differed significantly. Hunt, along with John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), represented a different, more radical current in Victorian art compared to Goodall's more traditional academic approach.

As a prominent Royal Academician, Goodall would have regularly interacted with fellow members at Academy functions, exhibitions, and committees. He was a contemporary of figures like Leighton, Poynter, Millais (who also served as RA President), George Frederic Watts (1817-1904), and William Powell Frith (1819-1909). While their artistic styles and chosen subjects varied widely – from Leighton's Neoclassicism to Frith's detailed panoramas of modern life – they were all part of the same institutional framework and contributed to the diverse tapestry of Victorian art. Goodall carved his own niche within this world, achieving considerable success through his specialization in Egyptian themes.

Challenges and Final Years

Despite the considerable success and fame Frederick Goodall enjoyed for much of his career, his later years were marked by declining fortunes. The immense popularity of his Orientalist paintings, which had commanded high prices during the mid-Victorian era, began to wane towards the end of the 19th century. Artistic tastes were changing, with the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and other modern movements challenging the dominance of academic and narrative painting. The public's fascination with Orientalist subjects, while still present, perhaps lost some of its novelty.

This shift in taste, combined possibly with financial mismanagement or the expenses associated with maintaining a large household and studio (he had several children), led to significant financial difficulties for the artist. His income diminished, and sadly, in 1902, just two years before his death, Frederick Goodall was forced to declare bankruptcy. This was a difficult end to a career that had seen such heights of professional success and public acclaim. It reflected the precariousness that even established artists could face when confronted with changing markets and artistic trends.

Frederick Goodall continued to paint into his final years, exhibiting at the Royal Academy until the year of his death. He passed away at his home in St John's Wood, London, on July 29, 1904, at the age of 82. He was buried in the historic Highgate Cemetery in North London, a resting place for many notable Victorian figures. His death marked the end of a long and productive life dedicated almost entirely to the pursuit of art, a life that witnessed the evolution of British painting across more than six decades.

Legacy and Conclusion

Frederick Goodall RA leaves behind a substantial legacy as one of Britain's most prominent and prolific Orientalist painters. His career trajectory, from accomplished painter of British rural and historical scenes to a celebrated specialist in Egyptian subjects, mirrors the Victorian era's expanding horizons and its complex engagement with the wider world. His dedication to capturing the landscapes, people, and customs of Egypt, informed by his own travels and experiences, resulted in a body of work that significantly contributed to the visual culture of Orientalism in Britain.

His paintings were admired in his time for their technical skill, detailed observation, rich colour, and evocative atmosphere. Works like The Finding of Moses, Early Morning in the Wilderness of Shur, and The Subsiding of the Nile remain key examples of 19th-century British Orientalism. His particular focus on integrating biblical narratives with observed Egyptian settings offered a distinctive contribution, attempting to bridge the gap between ancient texts and contemporary Victorian understanding of the Near East. While modern perspectives may critique the inherent romanticization and potential ethnographic inaccuracies within Orientalist art, Goodall's work provides valuable insight into the Victorian worldview and artistic preoccupations.

Today, Frederick Goodall's paintings are held in numerous public collections in the United Kingdom and beyond, including the Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the Guildhall Art Gallery in London, and various regional museums. While perhaps not as widely known now as some of his contemporaries like the Pre-Raphaelites or leading figures like Turner or Constable, his work remains significant for understanding the breadth and popularity of academic and narrative painting in the 19th century, and particularly for his role in shaping the British vision of Egypt. He stands as a testament to a lifetime of dedicated artistic practice, navigating the changing tides of taste while remaining true to his chosen path.