Charles Edward Perugini (1839-1918) stands as a notable figure in the landscape of Victorian art, an artist whose Italian origins and British upbringing fused to create a distinctive body of work. Primarily celebrated for his graceful depictions of women and children, idyllic classical scenes, and insightful portraiture, Perugini navigated the artistic currents of his time with a refined sensibility. His career, intertwined with some of the most prominent figures of the era, including his mentor Frederic, Lord Leighton, and his wife Kate Perugini, daughter of the novelist Charles Dickens, offers a fascinating glimpse into the artistic and social fabric of late 19th-century Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Italy and England

Born Carlo Perugini in Naples on September 1, 1839, his early life was steeped in the rich artistic heritage of Italy. The vibrant culture and classical ruins of his homeland undoubtedly left an indelible mark on his young imagination. Around the age of six, in approximately 1845, his family made the significant move to England, where they resided for about seven years. This early exposure to British life would prove formative, laying the groundwork for his later assimilation into the English art world.

Despite this period in England, Perugini's foundational artistic training took place back in Italy. He studied under the guidance of respected Italian masters, including Giuseppe Bonolis and Giuseppe Mancinelli. These artists, working within the academic traditions of the time, would have instilled in him a strong grounding in draughtsmanship, composition, and the classical ideals that were still highly valued. Bonolis, known for his historical and religious paintings, and Mancinelli, a prominent figure in the Neapolitan Academy, provided Perugini with the technical skills essential for a successful artistic career.

His pursuit of artistic excellence also led him to Paris, a major hub of artistic innovation and academic training in the 19th century. There, he studied with Ary Scheffer, a Dutch-French Romantic painter. Scheffer, known for his sentimental and often literary or religious subjects, painted with a polished technique. This experience in Paris would have broadened Perugini's artistic horizons, exposing him to different stylistic approaches and thematic concerns prevalent on the Continent, further enriching the Italian academic training he had received.

The Pivotal Influence of Frederic Leighton

A defining moment in Perugini's career came with his association with Frederic, Lord Leighton, one of the most eminent figures of British Victorian art. Leighton, a leading proponent of Neoclassicism and a central figure in the Olympic Games of art, encountered Perugini, likely recognizing his talent and potential. By 1863, Leighton had brought Perugini back to England, where he became an assistant in Leighton's studio. This was a period of immense learning and absorption for the younger artist.

Working in close proximity to a master like Leighton provided Perugini with unparalleled insight into the creation of large-scale, highly finished academic paintings. Leighton's own work, characterized by its meticulous detail, harmonious compositions, and idealized figures often drawn from classical mythology and history, profoundly influenced Perugini's artistic direction. It was under Leighton's influence that Perugini began to more seriously explore classical themes and refine his technique to achieve a similar level of polish and elegance. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau in France were part of a similar academic tradition that valued historical accuracy and technical perfection, a standard Leighton also upheld.

The mentorship extended beyond mere technical instruction; it also provided Perugini with access to Leighton's influential circle and an understanding of the workings of the London art world, particularly the Royal Academy of Arts, which was the dominant institution for artists seeking recognition and patronage. This period was crucial in shaping Perugini's mature style and launching his independent career.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Charles Edward Perugini's artistic style is best characterized as a blend of Neoclassicism and Victorian sentimentality, often infused with a gentle Romanticism. His Italian heritage and training provided a foundation in classical aesthetics, while his life in England and association with Leighton steered him towards the prevailing tastes of the Victorian era. He was particularly adept at capturing an air of refined elegance and quiet contemplation in his subjects.

His paintings often feature beautifully rendered figures, particularly women and children, in domestic settings or idyllic, vaguely classical landscapes. There is a softness and delicacy to his brushwork, and his palette tends towards harmonious, often muted tones, though he could also employ richer colors when the subject demanded. Unlike the more overtly narrative or moralizing works of some of his contemporaries, Perugini's paintings often evoke a mood or a moment of quiet introspection.

The influence of the Aesthetic Movement, which prioritized "art for art's sake" and the pursuit of beauty, can also be discerned in his work, particularly in his focus on decorative qualities and the creation of visually pleasing compositions. While not as radical as figures like James McNeill Whistler, Perugini shared a concern for aesthetic harmony. His classical scenes are less about dramatic storytelling and more about creating an atmosphere of timeless beauty and tranquility, reminiscent of the work of artists like Lawrence Alma-Tadema, though Perugini's touch was often gentler and less archaeologically specific.

Key Works and Their Significance

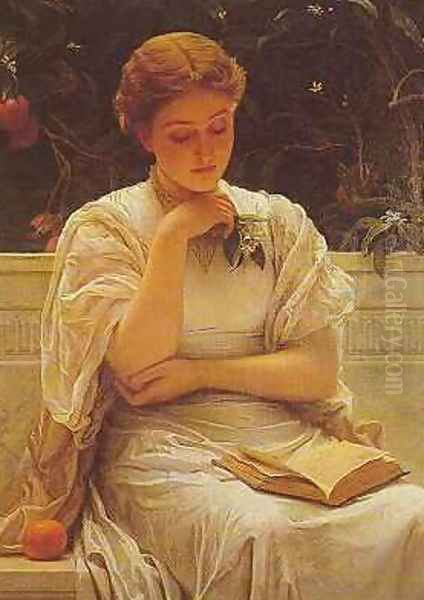

Perugini's oeuvre includes numerous paintings that exemplify his characteristic style and thematic preferences. Girl Reading, for instance, is a quintessential Perugini subject. It depicts a young woman absorbed in a book, a common Victorian theme reflecting increasing literacy and the romantic ideal of the contemplative female. The painting showcases his skill in rendering textures, the gentle fall of light, and the quiet psychology of his sitter. It is a work that speaks to the Victorian appreciation for domestic tranquility and refined leisure.

Dolce far Niente (Sweet Doing Nothing), a title used for several of his works and a popular theme among Victorian artists, perfectly encapsulates his interest in depicting moments of languid repose and beauty. These paintings often feature elegantly attired women in relaxed poses, sometimes in classical or Italianate settings, embodying an ideal of effortless grace. The 1882 version is a prime example, showcasing his mastery of drapery and serene expression.

His classical subjects, such as Pompeian Interior (1870) and Pandora (1893), demonstrate his engagement with the Neoclassical revival. Pompeian Interior reflects the Victorian fascination with the archaeological discoveries at Pompeii, offering a glimpse into a romanticized ancient world. Pandora, a subject tackled by many artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, allowed Perugini to explore themes of beauty, curiosity, and consequence through a mythological lens.

Fresh Lavender (1878) is another charming example of his genre painting, likely depicting a young woman with freshly gathered lavender, evoking sensory pleasures and a connection to nature. A Willing Slave (1900) might suggest a more allegorical or symbolic theme, common in late Victorian art, where figures could represent abstract concepts. The Loom, painted during his association with Leighton, shows his early foray into classical genre scenes, depicting women engaged in traditional crafts, a theme also explored by Leighton himself.

A particularly poignant work is Of an Hand Touching a Vanishing Hand, a portrait of his wife, Kate, likely imbued with personal meaning and reflecting the Victorian era's complex relationship with memory and loss. These works, exhibited regularly at prestigious venues like the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery, solidified his reputation as a painter of charm and technical skill.

Marriage to Kate Dickens and the Literary Connection

In 1873, Charles Edward Perugini secretly married Catherine Elizabeth Macready Dickens, known as Kate. She was the youngest surviving daughter of the celebrated novelist Charles Dickens and Catherine Hogarth. Kate was herself an accomplished painter and had previously been married to the artist Charles Allston Collins, a friend of the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais and brother of the novelist Wilkie Collins. Charles Allston Collins died in 1873, and Kate and Perugini held a formal wedding ceremony in 1874.

This marriage brought Perugini into the heart of one of England's most prominent literary families. The Dickens circle was extensive and influential, and this connection undoubtedly broadened Perugini's social and intellectual horizons. Kate was a talented artist in her own right, exhibiting her work, particularly portraits of children, and sharing a studio with her husband. Their shared artistic pursuits likely fostered a supportive and creative domestic environment.

The connection to Charles Dickens, who had passed away in 1870, still cast a long shadow. Perugini would have been privy to the family's memories and the ongoing legacy of the great novelist. This familial tie also brought him into contact with other figures from the literary and artistic worlds who had been close to Dickens or his family, such as Millais, who was a close friend of Kate's and had painted her portrait. The marriage lasted until Perugini's death and was by all accounts a companionable one.

The Artists Rifle Corps and Social Circles

Beyond his studio practice, Perugini was involved in the broader artistic community. In 1863, the same year he first exhibited at the Royal Academy, he joined the Artists Rifle Corps. This volunteer corps, officially the 20th (Artists') Middlesex Rifle Volunteers, was founded in 1860 in response to a perceived threat of invasion from France. It attracted a diverse membership from London's artistic and intellectual circles.

The Corps was co-founded by the painter Henry Wyndham Phillips and Frederic Leighton, Perugini's mentor, who served as its first commanding officer. Other prominent members included painters like John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Val Prinsep, and George Frederic Watts, as well as writers like William Morris and architects. For Perugini, joining the Artists Rifle Corps was not just a patriotic gesture but also a way to network and socialize with his peers. It provided a sense of camaraderie and a shared identity outside the competitive environment of the art market.

His involvement in such groups, along with his regular participation in exhibitions at the Royal Academy, the Grosvenor Gallery, and other venues, indicates his active engagement with the Victorian art scene. He was part of a generation of artists who benefited from the era's prosperity and the burgeoning middle-class appetite for art, which supported a wide range of styles and subjects.

Later Career, Recognition, and Exhibitions

Charles Edward Perugini enjoyed a consistently successful career, maintaining a steady output of paintings that appealed to Victorian tastes. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1863 until the year of his death, a testament to his enduring relevance and the consistent quality of his work. His paintings were also shown at the British Institution, the Society of British Artists, the Grosvenor Gallery (a more progressive alternative to the RA, favored by Aesthetic Movement artists), and the New Gallery, among others.

His works were often praised for their charm, refinement, and technical accomplishment. While he may not have achieved the monumental fame of his mentor Leighton or the revolutionary impact of the Pre-Raphaelites, Perugini carved out a respected niche for himself. He was a reliable producer of pleasing and well-crafted pictures that found favor with collectors and the public alike. His portraits were sought after, and his genre scenes, with their gentle sentiment and aesthetic appeal, were well-suited to Victorian interiors.

The art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was undergoing significant changes, with the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism challenging academic traditions. However, artists like Perugini, Edward Poynter (another prominent academician and contemporary), and Alma-Tadema continued to find an audience for their more traditional styles, which emphasized narrative clarity, technical finish, and idealized beauty. Perugini's ability to adapt slightly while retaining his core style allowed him to remain active and respected throughout his long career.

Legacy and Distinguishing from Pietro Perugino

Charles Edward Perugini passed away in London on December 22, 1918. He left behind a body of work that reflects the sensibilities and artistic preoccupations of the Victorian era. His paintings, characterized by their elegance, gentle sentiment, and technical polish, offer a window into a world that valued beauty, domesticity, and a romanticized vision of the classical past.

It is important to distinguish Charles Edward Perugini from the much earlier Italian Renaissance master Pietro Perugino (c. 1446/1452 – 1523). Pietro Perugino, born Pietro Vannucci, was a leading painter of the Umbrian school and famously the teacher of Raphael. His serene and devotional works had a profound impact on the High Renaissance. There is no direct artistic lineage or familial connection between the two artists despite the similarity in their surnames; Charles Edward Perugini's surname was his family name, not an adopted moniker related to the Renaissance master.

Charles Edward Perugini's influence on subsequent generations of artists was perhaps more subtle than that of some of his more groundbreaking contemporaries. However, his contribution lies in his consistent production of high-quality academic art that pleased and comforted his audience. He represents a significant strand of Victorian painting that, while sometimes overshadowed by more avant-garde movements, was immensely popular and culturally significant in its time. His work continues to be appreciated for its charm, craftsmanship, and embodiment of Victorian aesthetic ideals. His paintings can be found in various public and private collections, serving as a reminder of a talented artist who skillfully navigated the rich and complex art world of his day.

Conclusion

Charles Edward Perugini was an artist who successfully bridged his Italian heritage with the artistic environment of Victorian Britain. From his early training in Italy and Paris to his pivotal association with Frederic, Lord Leighton, and his long and productive career in London, Perugini consistently created works of art that were admired for their elegance, technical skill, and gentle sentiment. His depictions of women, children, and classical idylls captured the prevailing tastes of his era, while his marriage to Kate Dickens placed him within a notable literary and artistic milieu. As a respected member of the Royal Academy and a participant in the wider artistic community, Perugini left a legacy of charming and beautifully crafted paintings that continue to offer insight into the aesthetic values of the Victorian age. He remains a noteworthy figure for those studying the diverse tapestry of 19th-century British art.