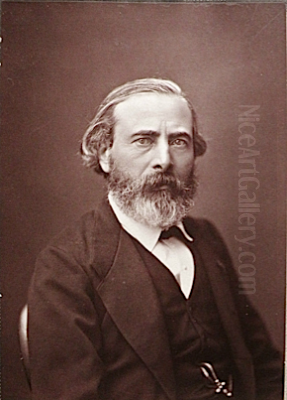

Pierre Edouard Frère stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century French art, celebrated for his sensitive and intimate portrayals of domestic life, particularly focusing on the world of children and the rural working class. Born in Paris on January 10, 1819, and passing away in Écouen on May 23, 1886, Frère carved a distinct niche for himself within the broader movement of Realism. His work is often associated with the "Art of Compassion," a tendency characterized by its empathetic and dignified representation of ordinary people and their daily struggles and simple joys. Through his warm palette, delicate execution, and keen observation, Frère offered viewers a window into the humble interiors and quiet moments that defined much of French provincial life during his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Frère's journey into the world of art began in his youth in Paris. His father was a music publisher, suggesting a household where creative pursuits were likely valued, potentially fostering his early interest in the arts. At the age of seventeen, in 1836, his formal artistic training commenced when he entered the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution was the bedrock of academic art training in France, emphasizing classical principles, drawing from life, and historical subjects.

His primary mentor at the École was Paul Delaroche, a highly respected and successful painter known for his meticulously rendered historical scenes, often depicting poignant moments from French and English history. Delaroche's studio was a significant training ground for many aspiring artists. Under his tutelage, Frère would have honed his skills in drawing, composition, and the precise rendering of figures and textures – skills that would later serve him well, albeit applied to very different subject matter than his master's grand historical narratives. While absorbing the technical rigour of Delaroche's teaching, Frère's own artistic inclinations soon led him away from historical painting towards the more intimate sphere of genre scenes.

Debut at the Salon and Growing Recognition

Frère made his public debut as an artist at the Paris Salon, the official and highly influential art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Sources suggest his first appearance was either in 1842 or 1843. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers in the competitive Parisian art world. Frère quickly found favour, becoming a regular exhibitor at the Salon for decades, continuing until the year of his death in 1886.

His early submissions garnered positive attention, and official accolades soon followed. He received medals at the Salon, marking him as an artist of note. Records indicate he was awarded third-class medals in both 1851 and 1852, followed by a second-class medal in 1857. Perhaps the most significant official recognition came in 1855, the year of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, when he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour. This prestigious award cemented his status within the French art establishment and signaled the widespread appeal of his chosen themes and style.

Thematic Focus: Childhood and Domesticity

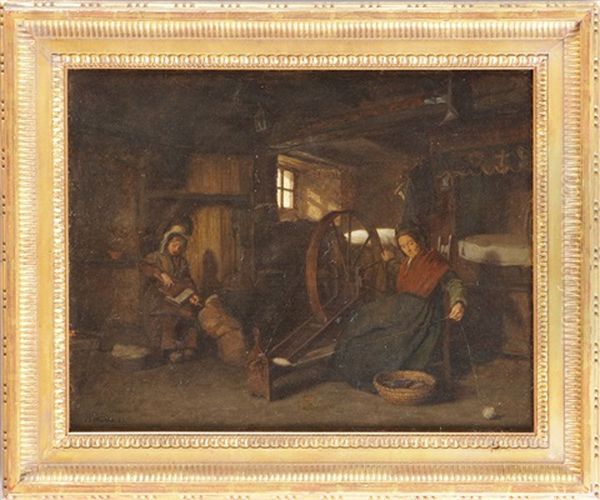

The heart of Pierre Edouard Frère's artistic output lies in his depictions of children and simple domestic life. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the innocence, concentration, and quiet dramas of childhood without resorting to excessive sentimentality. His young subjects are often shown engaged in everyday activities: learning to read, preparing a simple meal, playing quietly, or undertaking small household chores. Works like the celebrated La Tricoteuse (The Knitter or The Weaver Girl), which exists in several versions and is held in various museum collections, exemplify this focus. It portrays a young girl absorbed in the task of knitting, her expression one of serene concentration, embodying a sense of simple contentment and diligence.

Frère's paintings frequently transport the viewer into humble cottage interiors, illuminated by the soft light from a window or the warm glow of a hearth. He rendered these settings with care, detailing the textures of rough-hewn furniture, simple pottery, and homespun fabrics. Scenes like The Morning Meal (1856) or The Evening Prayer (1857, known through engravings after the painting) capture routines that defined the rhythm of rural life. These works resonated deeply with audiences who appreciated their perceived authenticity, moral undertones, and the quiet dignity they bestowed upon their working-class subjects. Frère's focus on the domestic sphere provided a comforting counterpoint to the rapid industrialization and social changes occurring elsewhere in France.

Style and Technique: Empathetic Realism

Frère's style is characterized by its warmth, intimacy, and meticulous execution. He typically employed a warm colour palette, favouring gentle earth tones, soft reds, and muted blues, which contributed to the cozy and inviting atmosphere of his scenes. His brushwork, while precise and controlled, particularly in rendering details of clothing, objects, and facial expressions, often retained a certain delicacy and softness, avoiding the harshness found in the work of some other Realists like Gustave Courbet.

He was a master of capturing the effects of light, particularly the way it could model form and create mood within an interior space. His compositions are generally simple and direct, focusing attention on the figures and their activities. Unlike the more politically charged Realism of Courbet or the heroic depictions of peasant labour found in the work of Jean-François Millet, Frère's realism was gentler, infused with empathy and often a touch of quiet humour. He observed his subjects closely, capturing subtle gestures and expressions that conveyed their inner states. This approach, focusing on the emotional and relational aspects of everyday life, aligned him with the "Art of Compassion."

The Écouen Art Colony

Later in his career, Frère chose to leave the bustle of Paris and settle in the village of Écouen, located north of the capital. This move proved significant not only for his own work but also for the development of a distinct artistic community. Écouen, under Frère's influence, became a thriving art colony, attracting numerous French and international artists drawn to its picturesque setting and the collegial atmosphere fostered by Frère himself. He became the central figure of what is sometimes referred to as the "Écouen School."

Artists gathered there, often sharing Frère's interest in genre painting, rural subjects, and the depiction of children. Among the painters associated with the Écouen colony were Paul Seignac, known for his charming scenes of childhood, August Schenck, who also depicted rural life (though later became known for animal paintings, particularly sheep in snow), and Luigi Chialva. Evidence suggests Seignac, Schenck, and Chialva worked alongside Frère, contributing to the colony's output of popular interior scenes and realist landscapes that captured the spirit of the place.

Other artists connected to the Écouen circle included Théophile Duverger (though direct interaction records with Frère are scarce, their subject matter often overlapped), George Todd (one of Frère's students), Michel Arnould, Joseph Aufray, Pauline Bourges, André Dargles, Paul Soyer, Léon Dandas, and the American painter Henry Bacon. This community provided a supportive environment for artists to exchange ideas, share models, and collectively explore themes related to provincial life, contributing significantly to the popularity of this type of genre painting in the latter half of the 19th century.

International Recognition: The British Connection

While highly regarded in France, Pierre Edouard Frère achieved remarkable popularity and critical acclaim in Great Britain. His success across the Channel was significantly boosted by a solo exhibition held in London in 1854, organized by the influential Belgian art dealer Ernest Gambert. This exhibition brought his work to the attention of a wider British audience and, crucially, to the notice of the preeminent art critic of the era, John Ruskin.

Ruskin, a champion of Pre-Raphaelitism and a powerful voice in Victorian art criticism, was deeply impressed by Frère's paintings. In his influential "Academy Notes," Ruskin praised Frère's work for its truthfulness, its deep feeling, and its moral seriousness, qualities highly valued by the Victorian public. He lauded the "unconscious dignity" and "humility" he perceived in Frère's depictions of children and peasants, finding in them a refreshing lack of affectation. Ruskin's endorsement provided an invaluable boost to Frère's reputation in Britain.

Following this critical success, Frère exhibited frequently at the Royal Academy in London, where his works were consistently well-received by both critics and the public. His paintings appealed to Victorian tastes, which often favoured narrative clarity, relatable human sentiment, and subjects perceived as morally wholesome. British collectors eagerly acquired his works; notable patrons included figures like Schwabe and Samuel Mendel, whose collections featured multiple examples of Frère's paintings. This strong British connection ensured Frère's influence extended well beyond the borders of France.

Frère as a Mentor

Beyond his own artistic production and his role as a central figure in the Écouen colony, Frère was also known as a dedicated and supportive teacher. He took on numerous pupils, guiding them in their artistic development. His teaching likely emphasized the careful observation, technical precision, and empathetic approach that characterized his own work. He seems to have taken a genuine interest in the careers of his students, actively promoting their work and maintaining relationships with them even after their formal studies concluded.

One notable student was the Anglo-American painter George Henry Boughton. Boughton studied with Frère in Écouen for a period, and Frère's influence can be discerned in Boughton's own later focus on historical genre subjects and carefully rendered figures. Frère reportedly helped his students by leveraging his connections with art dealers and collectors, facilitating introductions and helping them navigate the complexities of the art market. His willingness to nurture younger talent further solidified his importance within the artistic community of his time.

Later Career and Legacy

Pierre Edouard Frère remained active as a painter and continued to exhibit his work, primarily at the Paris Salon, until his death in Écouen in 1886. Throughout his long career, he remained largely faithful to the themes and style that had brought him success: intimate scenes of childhood, domesticity, and the quiet virtues of humble life. While artistic tastes began to shift dramatically in the later 19th century with the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Frère's work retained a loyal following, particularly among middle-class audiences in France and Britain.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the genre painting tradition and his role within the "Art of Compassion." He demonstrated that everyday subjects, treated with sensitivity and technical skill, could be as compelling as grand historical or mythological themes. He elevated the depiction of children beyond mere anecdote or cloying sentimentality, capturing their world with genuine insight. His influence extended through the Écouen colony and his numerous students, helping to popularize realist depictions of rural and domestic life. Today, his works are held in numerous public and private collections, including the Hamburg Kunsthalle (where works arrived as part of the Ary Scheffer bequest, linking him tangentially to another prominent artist of the era) and likely many other museums in France, Britain, and the United States, attesting to his enduring appeal.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Frère's oeuvre and thematic concerns:

La Tricoteuse (The Knitter/Weaver Girl): As mentioned, this is perhaps his most iconic theme, depicting a young girl engrossed in her knitting. It embodies the quiet dignity, concentration, and simplicity that Frère often sought to capture in his portrayals of childhood. Multiple versions exist, highlighting its popularity.

The Morning Meal (1856): This oil painting (22 x 18 inches) likely portrays a simple domestic scene, focusing on the routine of daily life in a humble setting. The date places it within the period of his rising recognition.

The Evening Prayer (1857): Known widely through engravings, this work presumably depicted a family or child engaged in prayer, reflecting the gentle piety often associated with idealized representations of rural life in the 19th century. Its date follows his Legion of Honour award.

Girl by the Fireside (1866): A small oil painting (approx. 9.8 x 3.9 inches), this work likely captures an intimate moment of a child near the hearth, a recurring motif in Frère's work symbolizing warmth and domesticity. Its estimated auction value (£500-£800) suggests continued collector interest in his smaller works.

The Art Critic: Described as a watercolor (10.5 x 7.75 inches), this work presents a slight puzzle if dated 1974, which is impossible for Frère. It's more likely the date refers to a later event (like a sale or acquisition) or is simply an error in the source data. An auction record from February 2023 notes a sale price between £600-£800. The title suggests a potentially more narrative or humorous scene than his typical domestic subjects.

These works, varying in scale and specific subject, consistently reflect Frère's focus on intimate moments, his warm style, and his empathetic view of his subjects.

Conclusion

Pierre Edouard Frère occupies a respected place in the history of 19th-century French art. As a leading exponent of genre painting focused on childhood and humble domesticity, he captured the quiet rhythms and simple virtues of provincial life with unparalleled sensitivity and technical finesse. His association with the "Art of Compassion" highlights the empathetic core of his work, which found favour both in his native France and, notably, in Victorian Britain, thanks in part to the influential endorsement of John Ruskin. Through his paintings and his role as a mentor within the Écouen art colony, Frère shaped a particular vision of realism – one characterized by warmth, intimacy, and a profound respect for the dignity of ordinary people. His art continues to resonate with viewers drawn to its gentle humanity and masterful depiction of the everyday.