Charles Émile Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet, often known simply as Émile Vernet-Lecomte, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Born into a lineage practically synonymous with artistic prowess, he carved his own niche, particularly within the captivating realm of Orientalism. His life, spanning from March 15, 1821, to November 19, 1900, witnessed profound societal and artistic transformations, and his work offers a fascinating window into the European fascination with the East, as well as the enduring appeal of meticulous portraiture.

An Illustrious Artistic Lineage

To understand Lecomte-Vernet, one must first appreciate the formidable artistic heritage from which he sprang. The Vernet name resonated through French art history for generations. His most celebrated ancestor was his great-grandfather, Claude Joseph Vernet (1714–1789), a preeminent landscape and marine painter whose dramatic seascapes and serene port scenes were highly sought after throughout Europe. Claude Joseph's son, Antoine Charles Horace Vernet, known as Carle Vernet (1758–1836), Émile's maternal grandfather, excelled in depicting horses, battle scenes, and contemporary life with a vibrant, dynamic style, becoming a favored painter of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Carle's son, Horace Vernet (1789–1863), Émile's uncle, achieved even greater international fame. Horace was a prolific painter of battles, historical subjects, and portraits, and also an early adopter of Orientalist themes, traveling extensively in North Africa. His studio was a hub of artistic activity, and his influence on the depiction of military glory and exotic locales was immense. Émile's own father, Hippolyte Lecomte (1781–1857), was himself a respected battle painter, a student of Jean-Baptiste Regnault and Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, and married Camille, the daughter of Carle Vernet, thus cementing the artistic fusion of the Lecomte and Vernet families. This environment, steeped in artistic tradition, discussion, and practice, undoubtedly shaped young Émile's aspirations and provided him with an unparalleled early education in the arts.

Early Career and Artistic Formation

Born in Paris, Charles Émile Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet naturally gravitated towards an artistic career. He received formal training under prominent academic painters, most notably Léon Cogniet (1794–1880), a highly respected artist known for his historical paintings and portraits, and a teacher to many successful artists of the era, including Léon Bonnat and Jean-Paul Laurens. Cogniet's rigorous instruction would have instilled in Lecomte-Vernet a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the academic tradition. His uncle, the celebrated Horace Vernet, also played a significant role in his artistic development, likely providing guidance and exposure to the burgeoning interest in Orientalist subjects.

Lecomte-Vernet made his official debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1843. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to exhibit their work and gain recognition, and a successful showing could launch a career. For his first Salon, he presented portraits, a genre in which he quickly demonstrated considerable skill. His talent was acknowledged with a third-class medal (bronze), a significant achievement for a young artist. It was around this time that he began to sign his works "Vernet-Lecomte," a clear nod to his illustrious maternal lineage and a strategic branding that would immediately associate him with the esteemed Vernet name. His early works primarily focused on portraits of the French aristocracy and the affluent bourgeoisie, subjects that demanded elegance, refinement, and a keen eye for capturing both likeness and social standing.

The Allure of the Orient: A Pivotal Shift

While his early portraiture was successful, Lecomte-Vernet's artistic trajectory took a defining turn towards Orientalism around 1847. This shift was part of a broader cultural phenomenon in Europe, particularly in France and Britain, where the "Orient"—a term then encompassing North Africa, the Levant, and the wider Ottoman Empire—became a source of immense fascination. Artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), who had famously journeyed to Morocco in 1832, had already paved the way, bringing back vibrant sketches and painting exotic scenes that captivated the public imagination. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), though he never traveled to the East, created iconic odalisques that fueled the romanticized vision of the harem.

For Lecomte-Vernet, this was not merely a fashionable trend but a profound artistic engagement. He began exhibiting a series of portraits featuring Middle Eastern women at the Salon, a theme that would become central to his oeuvre. It is highly probable that, like his uncle Horace Vernet and contemporaries such as Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) or Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856), Lecomte-Vernet undertook voyages to the Near East – specifically Egypt, Syria, and Palestine – to gather firsthand experience, sketches, and artifacts. These travels were crucial for Orientalist painters, lending authenticity and a wealth of visual detail to their work, distinguishing them from those who relied solely on imagination or secondary sources.

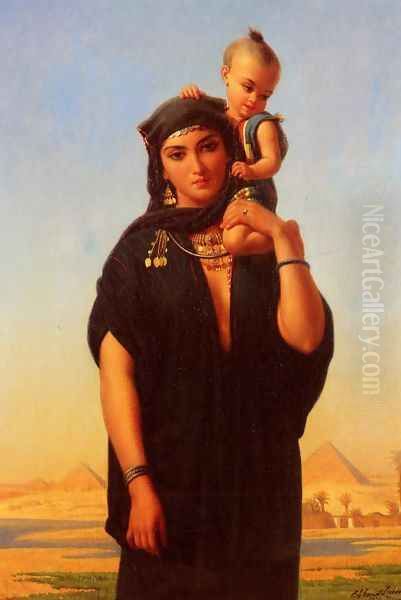

His Orientalist works moved beyond simple ethnographic documentation. Lecomte-Vernet sought to capture what he perceived as the essence and soul of his subjects, often imbuing them with a quiet dignity, a sense of mystery, or a gentle melancholy. His depictions of Middle Eastern women, in particular, became his hallmark, showcasing not only their traditional attire and adornments but also attempting to convey their inner lives, albeit through a 19th-century European lens.

Characteristics of Lecomte-Vernet's Orientalism

Lecomte-Vernet's Orientalist paintings are distinguished by several key characteristics. His academic training is evident in the meticulous draftsmanship and smooth finish of his canvases. He paid extraordinary attention to detail, rendering fabrics, jewelry, and architectural elements with precision. The textures of silk, velvet, intricate embroidery, and gleaming metalwork are often palpable in his paintings, contributing to the richness and verisimilitude of the scenes.

His use of color was both vibrant and nuanced. He employed a rich palette to convey the bright sunlight and colorful costumes of the East, but he also demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of tonal harmony. His compositions were carefully constructed, often focusing on single figures or small groups in intimate settings. These settings – whether the interior of a home, a quiet courtyard, or a suggestive glimpse into a harem – were designed to enhance the exotic atmosphere and provide a context for his subjects. Artists like John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876), a British Orientalist, also excelled in depicting detailed interiors, creating a sense of immersive realism.

A defining feature of Lecomte-Vernet's work is the psychological depth he often brought to his female subjects. While the Orientalist genre has faced criticism for its tendency to exoticize and objectify, Lecomte-Vernet's portraits frequently convey a sense of individual personality and emotion. His women are not mere decorative figures; they often possess a thoughtful, introspective, or even assertive gaze, challenging the viewer and hinting at a complex inner world. This sets some of his work apart from the more overtly sensual or passive depictions by some of his contemporaries. He seemed to blend a romantic sensibility with a desire for realistic portrayal, creating images that were both alluring and imbued with a sense of character.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

One of Lecomte-Vernet's most recognized works is The Egyptian Dancer or Almeh (often titled Jeune fille égyptienne or Egyptian Girl Emily), painted in 1869. This painting depicts a young woman, an Almeh (a traditional Egyptian female entertainer, skilled in singing and dancing), adorned in elaborate attire and jewelry, holding a stringed instrument. Her direct gaze and poised demeanor are captivating. The painting showcases his mastery in rendering textures—the sheen of her silk garments, the intricate patterns of her headdress, and the gleam of her ornaments. The rich colors and careful attention to ethnographic detail are characteristic of his mature Orientalist style.

Beyond idealized portraits of beautiful women, Lecomte-Vernet also explored other facets of Middle Eastern life. He painted street scenes, market encounters, and domestic interiors, often populated with figures in traditional dress. These works, while less focused on individual portraiture, contributed to the broader European visual understanding—or construction—of the Orient. His works often carried titles like Femme fellah portant son enfant, Égypte (Fellah Woman Carrying Her Child, Egypt) or Beauté juive de Maroc (Jewish Beauty of Morocco), indicating a specific ethnographic interest.

His oeuvre also included genre scenes that sometimes hinted at narrative. For instance, a painting depicting a Nubian Guard or an Arab Chief would evoke a sense of authority and exotic power, themes popular with European audiences. The allure of the "other," combined with skilled academic execution, ensured a steady demand for his paintings. Other French Orientalists like Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887), known for his depictions of Algerian life, or Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902), famous for his grand harem scenes, explored similar territories, each with their unique stylistic inflections.

Depicting History and Current Events

Interestingly, Lecomte-Vernet did not confine himself solely to the romanticized or ethnographic aspects of the Orient. He also turned his brush to contemporary historical events, a practice perhaps inherited from his father and uncle, both renowned for their battle paintings. He created works depicting scenes from the Crimean War (1853–1856), a conflict that pitted Russia against an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, Britain, and Sardinia. These paintings would have resonated with a French public keenly interested in the exploits of their military.

Furthermore, he addressed more harrowing contemporary events, such as the 1860 civil conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus. During this conflict, Druze and some Sunni Muslim factions engaged in widespread massacres of Maronite and other Christian communities. Lecomte-Vernet's depiction of such events, for example, a piece titled Massacre of the Maronites in Syria by the Druzes, demonstrated a willingness to engage with the harsher realities of the regions he otherwise often romanticized. This aspect of his work shows a broader engagement with the political and social currents of his time, moving beyond purely aesthetic or exotic concerns. This engagement with current events was shared by other artists, such as Édouard Manet (1832-1883) with his Execution of Emperor Maximilian.

Lecomte-Vernet and His Contemporaries

The 19th century was an era of immense artistic diversity in France. While Lecomte-Vernet operated primarily within the academic and Orientalist spheres, the art world around him was dynamic. The Barbizon School, with artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) and Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), was revolutionizing landscape and peasant genre painting. Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) was championing Realism, challenging academic conventions with his unvarnished depictions of everyday life. Later in Lecomte-Vernet's career, Impressionism, led by figures such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917), would radically alter the course of Western art.

Within the Orientalist camp itself, there was a wide spectrum of approaches. Delacroix brought a Romantic fervor and painterly dynamism. Gérôme, a rival of sorts to Horace Vernet and a hugely successful academic, was known for his highly polished, almost photographic realism and meticulously researched historical and ethnographic scenes. Artists like Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847–1928), an American who studied with Gérôme in Paris, and European painters such as Ludwig Deutsch (1855–1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854–1932), both Austrian-born but active in Paris, pushed this detailed, ethnographic realism even further, often specializing in specific types of scenes or figures. Lecomte-Vernet's style, while academically polished, often retained a softer, more romantic touch compared to the sometimes stark precision of Gérôme or Deutsch.

His participation in the Salons meant he was exhibiting alongside all these diverse talents, contributing to the vibrant, competitive, and ever-evolving Parisian art scene. His consistent output and the popularity of Orientalist themes ensured his continued presence and reputation.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Charles Émile Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet continued to paint and exhibit throughout his long career. He remained committed to his Orientalist subjects, which found a ready market among collectors and the public. His works were acquired by provincial museums in France, such as the Musée municipal in La Roche-sur-Yon and the Musée Calvet in Avignon, the latter being a particularly fitting home given its strong connection to the Vernet family, especially Claude Joseph Vernet, many of whose works are housed there.

He passed away in Paris on November 19, 1900, at the age of 79, leaving behind a substantial body of work. While perhaps not achieving the towering fame of his uncle Horace Vernet or the revolutionary impact of the Impressionists, Lecomte-Vernet made a distinctive contribution to 19th-century French art. His paintings offer a valuable insight into the Orientalist movement, reflecting both its artistic merits and its complex cultural implications.

Today, his works are appreciated for their technical skill, their evocative portrayal of Middle Eastern subjects, and their place within the broader narrative of European art's engagement with the East. They serve as important documents of a particular historical moment and artistic sensibility. His ability to combine academic precision with a romantic and often empathetic portrayal of his subjects ensures his continued relevance for art historians and enthusiasts alike. The name Lecomte-Vernet, bridging two artistic families, remains a testament to a rich and enduring artistic tradition. His paintings continue to appear in auctions and are held in public and private collections worldwide, allowing new generations to encounter his unique vision of the Orient.

Conclusion

Charles Émile Hippolyte Lecomte-Vernet was more than just an inheritor of a famous name; he was a dedicated and skilled artist who responded to the artistic currents of his time while forging his own path. His transition from society portraitist to a specialist in Orientalist themes reflects both personal inclination and a broader cultural fascination. Through his meticulous technique, sensitive portrayal of his subjects, and engagement with both the romantic allure and the contemporary realities of the East, Lecomte-Vernet created a body of work that remains captivating and historically significant. As a scion of the Vernet dynasty and a notable contributor to the Orientalist genre, he holds a secure place in the annals of 19th-century French art.