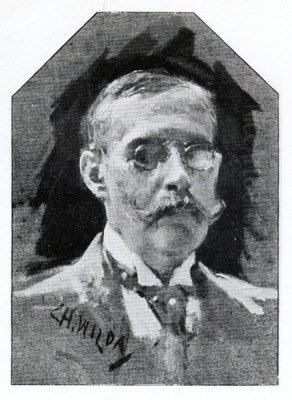

Charles Wilda, born Carl Wilda on December 20, 1854, in Vienna, Austria, and passing away in the same city on June 11, 1907, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century European art. He was a prominent Austrian painter, celebrated primarily for his contributions to the Orientalist genre. His meticulously detailed and evocative canvases transported Viennese audiences to the bustling markets, serene courtyards, and intimate interiors of North Africa and the Middle East, capturing a European fascination with these distant lands. Wilda's work is characterized by its vibrant color palettes, ethnographic precision, and a keen sense of narrative, making him a distinctive voice among his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born into a Vienna that was the vibrant capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Charles Wilda's early environment was steeped in culture and commerce. His father was a coffee house proprietor, a profession central to Viennese social and intellectual life. This setting might have exposed the young Wilda to a diverse array of people and stories, perhaps kindling an early interest in observing human interaction and diverse cultures. He was not the only artistic talent in his family; his brother, Gottfried Wilda, also pursued a career as a painter, suggesting a familial encouragement or predisposition towards the arts. It was during his formative years that Carl Wilda adopted the more internationally recognized "Charles."

Wilda's initial artistic training began under the tutelage of another Orientalist painter, Carl Müller (not to be confused with his later, more influential professor). This early exposure to Orientalist themes likely set the stage for his lifelong dedication to the genre. The allure of the "Orient"—a term then encompassing North Africa, the Levant, and the wider Middle East—was at its zenith in Europe, fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and a Romantic desire for the exotic and the picturesque.

Academic Foundations at the Vienna Academy

To formalize his artistic education, Charles Wilda enrolled in the prestigious Vienna Academy of Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). This institution was a bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and composition. It was here that Wilda came under the profound influence of Leopold Carl Müller, a leading figure in Austrian Orientalist painting and a highly respected professor at the Academy. Müller, often dubbed "Orient-Müller" or "Egypt-Müller" due to his extensive travels and specialization, had a significant impact on a generation of Austrian painters.

Under Leopold Carl Müller's guidance, Wilda honed his technical skills and deepened his understanding of the Orientalist genre. Müller himself was known for his vibrant depictions of Egyptian life, characterized by strong light effects and ethnographic detail. He encouraged his students to travel and observe firsthand the cultures they wished to depict. Other notable artists who benefited from Müller's tutelage around this period included Ludwig Deutsch, another Austrian who would achieve great fame in Paris for his meticulously detailed Orientalist scenes, the Serbian painter Paja Jovanović, known for his Balkan and Orientalist subjects, and the French-born Jean Discart, who also specialized in North African scenes. Wilda's education at the Academy, therefore, placed him directly within a thriving school of Orientalist thought and practice.

Journeys to the Orient: Firsthand Inspiration

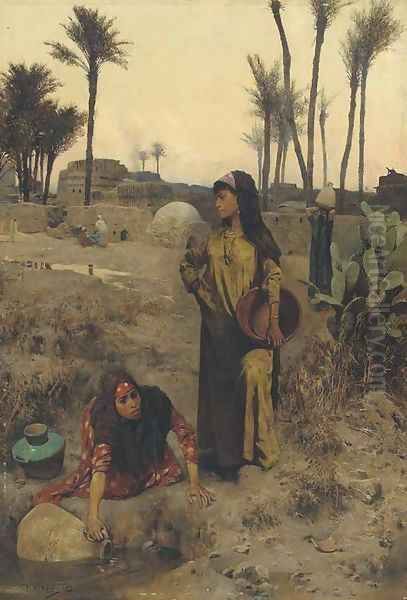

True to the spirit of Orientalist painters and the teachings of mentors like Leopold Carl Müller, Charles Wilda understood the importance of direct experience. In the 1880s, he embarked on significant travels, most notably to Egypt. These journeys were transformative, providing him with a wealth of sketches, photographs, artifacts, and, most importantly, firsthand impressions that would fuel his artistic output for years to come. He immersed himself in the sights, sounds, and atmosphere of Cairo and other locales, observing the daily life, architecture, costumes, and customs of the people.

This direct engagement with the subject matter was crucial for lending authenticity to his paintings, a quality highly valued by the European audience. Unlike some artists who relied on studio props and imagination, Wilda, like his contemporary Gustav Bauernfeind or the earlier John Frederick Lewis, sought to capture the genuine essence of the East. His travels allowed him to move beyond stereotypical representations and imbue his scenes with a greater sense of lived reality, even if filtered through a European artistic lens.

Artistic Style: Realism, Narrative, and Exotic Allure

Charles Wilda's artistic style is a compelling blend of academic realism and a subtle infusion of techniques that hint at a more modern sensibility. His primary commitment was to a detailed, almost photographic rendering of his subjects. He paid meticulous attention to the textures of fabrics, the intricacies of architectural details, the play of light and shadow, and the physiognomy of his figures. This precision aligned with the prevailing tastes of the academic art world and the expectations of patrons who desired visually rich and seemingly accurate portrayals of exotic lands.

A defining characteristic of Wilda's work is its strong narrative quality. His paintings are rarely static; they often depict moments of interaction, commerce, or quiet contemplation. Figures are engaged in activities—bargaining in a souk, playing music, conversing in a coffee house, or presenting wares. This imbues his canvases with a sense of dynamism and invites the viewer to imagine the stories unfolding within the scene.

His color palette was typically rich and vibrant, capturing the intense light and colorful attire associated with the Orient. He skillfully managed complex compositions, often featuring multiple figures and a wealth of decorative elements, without sacrificing clarity or focus. While firmly rooted in academic tradition, some sources note that Wilda occasionally incorporated impressionistic touches, perhaps in his handling of light or atmospheric effects, a combination considered somewhat rare for the time. This might suggest an awareness of contemporary artistic developments, even as he largely adhered to a more established style, much like his French contemporary Jean-Léon Gérôme, who, despite his academic precision, was a master of light and texture.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Charles Wilda produced a significant body of work, with several paintings standing out as representative of his skill and thematic concerns.

The Coffee-House is one of his most celebrated paintings. It depicts a traditional Middle Eastern coffee house, a central institution in social and commercial life. Wilda masterfully captures the atmosphere of the establishment, with figures engaged in conversation, smoking hookahs, and sipping coffee. The details, from the intricate patterns on the rugs and cushions to the attire of the men and the play of light filtering into the interior, are rendered with exquisite care. The scene is animated by subtle actions, such as a figure pouring a drink, which adds a dynamic quality to the composition. This work exemplifies Wilda's ability to create an immersive and believable environment.

The Egyptian Antiques Seller (1884) is another key work, reflecting the European fascination with ancient Egyptian history and the burgeoning trade in antiquities during the 19th century. The painting typically portrays a merchant displaying his wares—statues, pottery, and other artifacts—to potential customers or simply amidst his collection. Such scenes allowed Wilda to showcase his skill in rendering diverse textures and objects, while also tapping into the romantic allure of Egypt's ancient past. This theme was also popular with artists like Ludwig Deutsch and the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman.

Strike a Bargain (also known as The Bargain or similar titles depicting market interactions) highlights another common motif in Wilda's oeuvre: the bustling commerce of the souk or marketplace. These paintings are often filled with a variety of goods, from textiles and ceramics to metalwork and spices, and feature animated interactions between buyers and sellers. Wilda excelled at capturing the lively, crowded atmosphere of these commercial hubs, paying close attention to the diverse characters and their traditional dress.

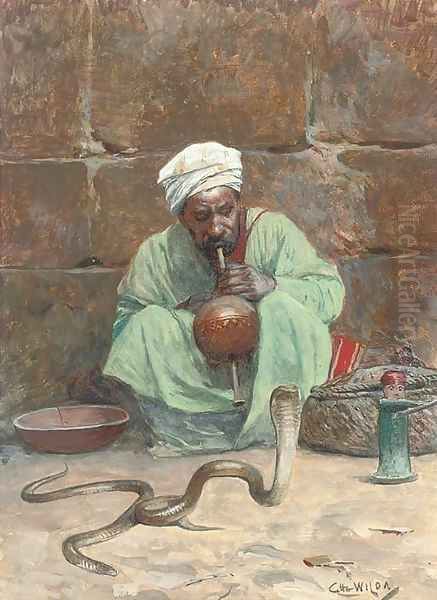

Other works, such as those depicting musicians, scholars, or domestic scenes, further illustrate his range within the Orientalist genre. His depictions of "snake charmers," a popular Orientalist trope also explored by artists like Gérôme and Giulio Rosati, were noted for their exoticism and were even used in later tourism promotions, attesting to their evocative power.

Exhibitions, Awards, and Collaborations

Charles Wilda was an active participant in the Viennese art scene and gained considerable recognition during his lifetime. He regularly exhibited his works in major contemporary exhibitions in Vienna and other European cities. His talent did not go unnoticed by the arbiters of taste and officialdom. In 1895, he was awarded the prestigious Kaiserpreis (Emperor's Prize), a significant honor that underscored his standing in the Austrian art world. This was followed in 1898 by the Gold State Medal, further cementing his reputation.

Beyond his solo endeavors, Wilda also engaged in collaborative projects. He is known to have shared a studio in Paris on the Boulevard de Clichy with the Hungarian-Italian Orientalist painter Arthur Ferraris during the late 1880s. This period in Paris, then the undisputed center of the art world, would have exposed Wilda to a vibrant international artistic community. Together, Wilda and Ferraris participated in the Exposition du Caire (Cairo Exhibition) in 1892, showcasing their Orientalist works directly in one of the locales that inspired them.

Wilda also contributed to larger public commissions. He was involved in the creation of a monumental historical painting, Emperor Barbarossa Arriving at the Danube, for the Vienna Art Exhibition of 1907. This project, reportedly commissioned by Vienna's influential mayor Karl Lueger, saw Wilda working alongside other notable Austrian artists of the period, such as a painter referred to as Adams (possibly John Quincy Adams, an Austrian painter of American descent), Albin Egger-Lienz (though Egger-Lienz's style was markedly different and more expressionistic), and Franz von Schramm. Such collaborations indicate Wilda's integration into the established artistic circles of Vienna.

Wilda and His Contemporaries: A Viennese Orientalist in a European Context

Charles Wilda operated within a flourishing European tradition of Orientalist painting. In Vienna, his teacher Leopold Carl Müller was a towering figure. Wilda's peers and fellow students of Müller, such as Ludwig Deutsch, Paja Jovanović, and Jean Discart, each carved out their own niches within the genre, often achieving international fame, particularly Deutsch with his highly polished scenes of Cairo. Another Austrian Orientalist of note, though more often associated with Paris, was Rudolf Ernst, known for his similarly detailed and richly colored depictions of Islamic life and interiors.

Beyond the Austrian sphere, the French school of Orientalism was particularly dominant, with Jean-Léon Gérôme as its leading proponent. Gérôme's highly finished, often dramatic or sensual, depictions of the East set a standard for many. Other French Orientalists included Eugène Fromentin, known for his depictions of Algeria, and Benjamin Constant. In Britain, artists like John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for a decade, and David Roberts, famous for his topographical views, made significant contributions. German Orientalists like Gustav Bauernfeind created incredibly detailed architectural and street scenes.

Wilda's work, while sharing the meticulous detail and ethnographic interest of many of these artists, often possessed a slightly softer, more intimate quality. He was less inclined towards the grand historical or overtly sensual themes favored by some of his French counterparts, focusing more on the everyday life and gentle interactions within carefully constructed settings. His position within the Viennese art scene was that of a respected academic painter specializing in a popular genre. While Vienna was also witnessing the rise of modernism with figures like Gustav Klimt and the Vienna Secession towards the end of Wilda's career, Wilda remained committed to a more traditional, representational style. He can be seen alongside artists like Hans Makart, who, though earlier and more flamboyant, represented a taste for the opulent and historical that characterized much of 19th-century Viennese painting before the avant-garde movements took hold.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

During his lifetime, Charles Wilda achieved considerable success and recognition. His paintings were sought after by collectors, and he received prestigious awards. His work satisfied the public's appetite for exotic imagery, providing a window into cultures that seemed both remote and fascinating. His detailed, narrative style made his paintings accessible and engaging.

However, in the broader sweep of art history, Charles Wilda, like many skilled academic painters of his era, has been somewhat overshadowed by the revolutionary artists who pioneered modernism. The Orientalist genre itself has also undergone critical re-evaluation in post-colonial discourse, with some scholars critiquing its tendency to exoticize, stereotype, or present a romanticized and sometimes patronizing view of non-European cultures.

Despite this, there is a renewed appreciation for the technical skill and artistic merit of painters like Wilda. His works are valued for their meticulous craftsmanship, their evocative power, and as historical documents reflecting 19th-century European perceptions and fascinations. His paintings continue to appear in art markets, with works like the aforementioned "Oriental beauty" fetching respectable prices, indicating an ongoing interest among collectors. His contribution to Austrian art, particularly within the Orientalist school fostered by Leopold Carl Müller, is undeniable. He successfully captured and conveyed the allure of the East to a Viennese audience, creating a body of work that remains visually captivating and rich in historical interest. His paintings offer a glimpse into a specific moment in cultural history, where the "Orient" served as a vast canvas for the European artistic imagination.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the East

Charles Wilda was a dedicated and highly skilled practitioner of Orientalist art. From his early training in Vienna to his formative travels in Egypt, he cultivated a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant color, and engaging narratives. His depictions of coffee houses, antique sellers, bustling markets, and quiet moments of daily life in the Middle East resonated deeply with his contemporaries, earning him accolades and a prominent place in the Viennese art world of the late 19th century.

While the broader currents of art history may have shifted focus towards the avant-garde, Wilda's work endures as a testament to the enduring appeal of the Orientalist genre and the high level of craftsmanship achieved by its practitioners. He remains an important figure for understanding Austrian art of his period and the complex European engagement with the cultures of the East. His paintings continue to enchant viewers with their intricate beauty and their power to transport us to a world meticulously imagined and artfully rendered.