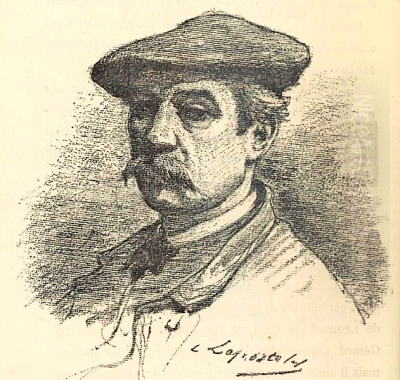

Charles Lapostolet stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. A dedicated painter of landscapes and, uniquely, of individual trees, he navigated the evolving artistic currents of his time, from the lingering influence of academic tradition to the burgeoning call for direct observation of nature. His work, characterized by a sensitive handling of light and a profound appreciation for the natural world, offers a window into an era of significant artistic transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on September 24, 1824, in Velars-sur-Ouche, a commune in the Côte-d'Or department of eastern France, Charles Lapostolet's early life was rooted in a region known for its picturesque landscapes. This environment likely played a formative role in shaping his artistic inclinations. His formal artistic training led him to the studio of Léon Cogniet (1794-1880), a highly respected painter and influential teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Cogniet himself was a versatile artist, known for his historical paintings, portraits, and Orientalist scenes, and his pupils included other notable artists such as Léon Bonnat and Edgar Degas, though Degas's path would diverge significantly.

Despite his tutelage under a prominent academic figure like Cogniet, Lapostolet developed a strong preference for working directly from nature, en plein air. This inclination placed him in sympathy with a growing movement among artists who sought to escape the confines of the studio and capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in the outdoors. While he absorbed the technical skills and discipline of academic training, his heart lay in the direct, unmediated experience of the landscape.

The Paris Salon and Emerging Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the preeminent venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition in 19th-century France. Lapostolet made his debut at the Salon in 1848, a year of significant political upheaval in France, and continued to exhibit there regularly until 1882. This long period of participation underscores his commitment to his craft and his engagement with the official art world, even as his personal artistic leanings embraced more progressive approaches to landscape.

His dedication and talent did not go unnoticed. Lapostolet received several accolades throughout his Salon career, including medals in 1870 and 1882. Some sources also indicate a gold medal in 1868. These awards were significant markers of success, signifying approval from the art establishment and enhancing an artist's reputation and marketability. For Lapostolet, they would have affirmed his position as a respected landscape painter among his peers.

The Sylvan Portrait: A Unique Specialization

One of the most distinctive aspects of Charles Lapostolet's oeuvre is his focus on what can be termed "tree portraits." His work L'Arbre (The Tree), created between 1845 and 1855, exemplifies this specialization. Executed with pencil and heightened with white on paper, these drawings are not mere botanical studies but rather sensitive, almost individualistic portrayals of trees. He captured their structural complexity, the texture of their bark, and the intricate patterns of their branches with a remarkable delicacy and precision.

These tree studies were considered quite modern for their time and served as exemplary exercises for other landscape painters. Lapostolet's approach to these subjects reveals an influence from 17th-century Dutch landscape painters, such as Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, who often gave trees a prominent, almost heroic role in their compositions. However, Lapostolet brought a 19th-century sensibility to this tradition, imbuing his trees with a quiet dignity and a sense of presence that was uniquely his own. He often depicted isolated trees, allowing their individual character to dominate the composition, creating a serene and contemplative atmosphere.

Broadening Horizons: From Burgundian Forests to Coastal Vistas

While his early work was naturally influenced by the landscapes of his native Burgundy, Lapostolet's artistic vision expanded significantly through travel. His journeys across Europe, particularly to other regions of France, Italy, and the Netherlands, exposed him to a diverse range of environments and artistic traditions. This exposure is reflected in the evolving subject matter of his paintings.

He became particularly adept at capturing coastal scenes and marine subjects, earning him the designation of a "peintre de la marine" (marine painter). His paintings of the Normandy coast, such as Bateaux de pêcheurs en Normandie (Fishing Boats in Normandy, 1882), showcase his ability to render the atmospheric conditions of the seaside, the play of light on water, and the daily life of fishing communities. Works like Marée haute; côte de Granville (High Tide; Granville Coast, 1879) and Marée montante; côte de Carolles (Rising Tide; Carolles Coast, 1880), both now in the collection of the Musée d'Orsay, further attest to his skill in this genre.

His travels also took him to Venice, a city that has captivated artists for centuries. His painting La Giudecca à Venise (The Giudecca in Venice, 1878), housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, demonstrates his ability to translate the unique light and architectural splendor of the Italian city onto canvas. Closer to home, Parisian scenes like Le Canal St Martin (1870), which found its way into the Luxembourg Museum (whose collections later formed a core part of the Musée d'Orsay), and La Seine à Auteuil (The Seine at Auteuil, 1872), now in the Rodin Museum, show his engagement with the urban landscape as well.

Artistic Style: Naturalism and the Pursuit of Light

Lapostolet's artistic style can be broadly categorized within the Naturalist movement that gained prominence in the latter half of the 19th century. Naturalism, an extension of Realism, sought an even more faithful and unembellished depiction of reality, often with a focus on the everyday and the observable world. In landscape painting, this translated into a meticulous attention to detail, accurate rendering of light and atmosphere, and a preference for direct observation.

His work shares affinities with the Barbizon School, a group of painters who gathered in the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau to paint directly from nature. Key figures of this school, such as Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Jules Dupré, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, championed a more direct and unidealized approach to landscape, moving away from the classical or romanticized landscapes that had previously dominated. While Lapostolet was a student of the more academic Cogniet, his preference for outdoor work and his detailed, naturalistic style align him with the spirit of the Barbizon painters. He is sometimes even considered a precursor or an affiliate of this movement.

Lapostolet's handling of light was particularly noteworthy. Whether depicting the dappled sunlight filtering through the leaves of a forest, the luminous haze of a coastal morning, or the reflective waters of a canal, he demonstrated a keen sensitivity to atmospheric effects. This focus on light was a hallmark of 19th-century landscape painting and a precursor to the Impressionists' more radical explorations of optical phenomena.

Connections and Contemporaries: A Rich Artistic Milieu

Charles Lapostolet operated within a vibrant artistic community. His teacher, Léon Cogniet, connected him to the academic establishment, but his own inclinations led him to associate with artists who shared his love for landscape and marine painting.

A significant friendship was with Eugène Boudin (1824-1898), a painter renowned for his marine scenes and beachscapes, particularly of the Normandy coast. Boudin, often called the "King of Skies," was a pivotal figure in the development of Impressionism and a mentor to the young Claude Monet. Lapostolet and Boudin reportedly met in Honfleur, a picturesque harbor town that attracted many artists, including Monet, Johan Barthold Jongkind, and Gustave Courbet. Their shared interest in capturing the fleeting atmospheric conditions of the coast would have provided fertile ground for their friendship and artistic exchange.

Another connection, albeit more familial, was to Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), one of the most influential landscape painters of the 19th century. Corot was a bridge figure between Neoclassicism and Impressionism, admired for his lyrical landscapes and his mastery of tonal values. Lapostolet's cousin, Auguste Chevran, was Corot's son-in-law, providing a potential, if indirect, link to this towering figure of French landscape art. Corot's own dedication to plein air painting and his sensitive depictions of trees and light would certainly have resonated with Lapostolet's artistic pursuits.

Lapostolet was also acquainted with the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875), a dynamic and expressive artist whose work often challenged academic conventions. While their primary mediums differed, their presence in the Parisian art world of the same era suggests overlapping circles.

The broader artistic landscape of Lapostolet's time included figures like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), the leading proponent of Realism, whose robust and unsentimental depictions of rural life and landscape had a profound impact. The Impressionist movement was also taking shape during the later part of Lapostolet's career, with artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) revolutionizing the way light and color were perceived and painted. While Lapostolet's style remained more rooted in Naturalism, he was undoubtedly aware of these radical new developments. Other landscape painters of note during this period included Henri Harpignies (1819-1916), known for his structured and luminous landscapes, often compared to Corot.

Notable Works and Their Enduring Qualities

Several of Charles Lapostolet's works have found homes in prestigious museum collections, a testament to their artistic merit.

L'Arbre (c. 1845-1855): As previously discussed, these drawings are central to understanding Lapostolet's unique contribution to the art of the tree. Their detailed execution and sensitive portrayal elevate the subject beyond mere study.

Le Canal St Martin (1870, formerly Luxembourg Museum, now likely part of Musée d'Orsay collections): This painting captures a slice of Parisian life, demonstrating his ability to find picturesque qualities within the urban environment. The St. Martin Canal was a popular subject for artists, offering interesting plays of light on water and reflections of buildings.

La Seine à Auteuil (1872, Rodin Museum, Paris): Another Parisian scene, this work likely depicts a tranquil stretch of the river, showcasing his skill in rendering water and atmospheric effects. Auteuil, at the time, was a suburban area that offered pastoral views along the Seine.

La Giudecca à Venise (1878, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna): This painting reflects his Italian travels and his engagement with the iconic Venetian cityscape. The Giudecca, a long island separated from the main islands of Venice by a wide canal, offers panoramic views that have attracted artists for centuries.

Marée haute; côte de Granville (1879, Musée d'Orsay, Paris): A depiction of the Normandy coast, likely capturing the dramatic effects of high tide. Granville was a popular coastal resort and fishing port.

Marée montante; côte de Carolles (1880, Musée d'Orsay, Paris): Similar to the Granville scene, this painting focuses on the dynamic nature of the sea along the Carolles coast, another scenic spot in Normandy.

Bateaux de pêcheurs en Normandie (1882): This oil painting further highlights his interest in marine subjects and the daily life of coastal communities.

These works, whether intimate drawings of trees or expansive coastal landscapes, are united by Lapostolet's careful observation, his skillful handling of his chosen medium, and his evident love for the natural world. His paintings often possess a quiet, contemplative quality, inviting the viewer to share in his appreciation of nature's subtle beauties.

Legacy and Contribution to Art History

Charles Lapostolet passed away in 1890. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary fame of some of his contemporaries like the Impressionists, his contributions to 19th-century French art are significant. He excelled in the genre of landscape and marine painting, creating works that were both technically accomplished and aesthetically pleasing.

His particular focus on "tree portraits" marks him as an artist with a unique vision. These works not only demonstrate his exceptional draughtsmanship but also reflect a deep, almost reverential connection to the individual forms of nature. In an era that saw landscape painting rise to unprecedented prominence, Lapostolet carved out a niche that was distinctly his own.

He successfully navigated the demands of the Salon system while staying true to his preference for direct observation and plein air work. His art represents a bridge between the more traditional approaches to landscape and the emerging modern sensibilities that would come to define the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His paintings and drawings can be found in public collections in France, including the prestigious Musée d'Orsay and the Rodin Museum, as well as in museums in the Netherlands and Belgium, indicating a broader appreciation for his work beyond his native country.

A Quiet Master of Observation

Charles Lapostolet's legacy is that of a dedicated and sensitive artist who found profound beauty in the natural world. From the intricate structures of individual trees to the expansive vistas of the French coast, he captured his subjects with a quiet mastery and an unwavering commitment to truthful representation. His work offers a valuable perspective on the artistic currents of 19th-century France, a period of immense creativity and change. As an accomplished landscape and marine painter, and a unique portrayer of sylvan forms, Charles Lapostolet deserves recognition for his distinct contribution to the rich heritage of French art. His paintings continue to speak to us today, evoking the timeless allure of nature and the enduring power of artistic observation.