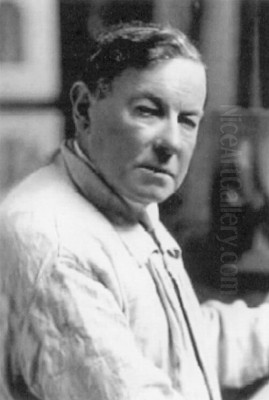

Robert Anning Bell (1863-1933) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British art, particularly flourishing during the zenith of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the burgeoning Art Nouveau style. A multifaceted artist, Bell's talents spanned painting, illustration, stained glass design, mosaic work, and low-relief sculpture, leaving an indelible mark on the decorative arts of his time. His commitment to craftsmanship, beauty, and the integration of art into everyday life and public spaces defined his prolific career.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Soho, London, on April 14, 1863, Robert Anning Bell's artistic journey began not in a painter's studio, but within the structured environment of his uncle's architectural practice. This early exposure to architectural drawing and design principles likely instilled in him a strong sense of form, structure, and the practical application of art, which would become hallmarks of his later work. This foundational experience provided a unique perspective that differentiated him from artists trained solely in the fine arts.

Seeking to refine his artistic skills, Bell enrolled at the Westminster School of Art. Here, he studied under Professor Frederick Brown, a notable art educator who would later become the Slade Professor of Fine Art. Brown's teaching emphasized strong draughtsmanship and a solid academic grounding. Following his studies at Westminster, Bell, like many aspiring artists of his generation, sought further refinement in Paris, the epicenter of the art world at the time. He joined the studio of Aimé Morot, a painter known for his historical scenes and portraits, where he would have been exposed to contemporary French academic and Salon painting traditions. This Parisian sojourn broadened his technical skills and artistic horizons. He also spent time in Italy, absorbing the lessons of the Renaissance masters, an influence that would become profoundly evident in his work.

Embracing the Arts and Crafts Ethos

Upon his return to England, Bell became deeply involved with the Arts and Crafts Movement, a phenomenon that sought to counteract the perceived dehumanizing effects of industrialization by championing handcrafted objects, traditional techniques, and the unity of art and design. Figures like William Morris and John Ruskin were pivotal in shaping the movement's philosophy, advocating for art that was both beautiful and useful, made by skilled artisans who took pride in their work.

Bell wholeheartedly embraced these ideals. He was a prominent member of the Art Workers' Guild, an organization founded in 1884 by a group of architects, designers, and craftsmen (including figures like Walter Crane and W.R. Lethaby) to promote the "unity of all the arts." Bell also exhibited regularly with the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, which provided a crucial platform for artists like him to showcase their diverse creations. His work exemplified the movement's aspiration to elevate the decorative arts to the same status as fine art.

Artistic Style and Diverse Influences

Robert Anning Bell's artistic style is characterized by its elegance, decorative richness, and a profound respect for tradition, skillfully blended with a contemporary sensibility. He is often cited as one of the last significant figures connected to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's legacy, not as a direct member, but as an artist whose work carried forward their romanticism, attention to detail, and often literary or allegorical subject matter. The influence of late Pre-Raphaelite artists like Sir Edward Burne-Jones, with his elongated figures and dreamlike compositions, can be discerned in Bell's work.

A particularly strong influence on Bell was the art of the Italian Renaissance, especially the work of sculptors like Luca della Robbia. Della Robbia's serene, beautifully crafted glazed terracotta reliefs, often depicting religious scenes or cherubic figures, resonated with Bell's own interest in low-relief sculpture and decorative panels. This Renaissance sensibility is evident in the clarity of Bell's compositions, the graceful lines of his figures, and his harmonious use of color.

In his illustrative work, Bell was also influenced by contemporaries such as Walter Crane, a leading figure in book illustration and design, known for his strong outlines and decorative patterning. The impact of artists like Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, who were also active in book design and illustration through their Vale Press, can also be considered part of the broader artistic milieu that shaped Bell's approach.

Mastery Across Multiple Media

Robert Anning Bell was a remarkably versatile artist, achieving distinction in an array of media. This adaptability was a key tenet of the Arts and Crafts ideal, where artists were often proficient in multiple disciplines.

Painting and Tempera Revival

While perhaps less known for his easel paintings than his decorative work, Bell was a skilled painter. He was particularly interested in the revival of tempera painting, a medium that had been largely superseded by oil paint since the Renaissance. Tempera, with its luminous, matte finish, appealed to Arts and Crafts artists for its historical associations and the meticulous craftsmanship it required. Bell's tempera painting, The Romance, is a notable example, showcasing rich, captivating colors and a lyrical quality. His paintings often featured allegorical or mythological themes, rendered with a characteristic grace and decorative flair.

Illustration: Bringing Literature to Life

Bell was a highly accomplished and sought-after illustrator. His work in this field perfectly embodied the Arts and Crafts emphasis on the "Book Beautiful," where the typography, illustration, and binding were all considered integral parts of a unified artistic whole. He provided illustrations for numerous books, including editions of Keats's poems, Shakespeare's plays, and various fairy tales and children's stories.

His illustrations for an 1895 edition of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream are among his most celebrated. These drawings are characterized by their delicate lines, imaginative compositions, and a whimsical, ethereal quality that perfectly captures the play's magical atmosphere. Other notable illustrative projects include Shakespeare's The Tempest and Macbeth. His style, influenced by Walter Crane and the linear elegance of artists like Aubrey Beardsley (though Bell's work was generally less decadent and more romantic), featured strong outlines, decorative patterning, and a harmonious integration of image and text. Beardsley himself, in his earlier period, is said to have drawn inspiration from Bell's illustrative style.

Mosaics: Monumental and Enduring Art

Bell excelled in the ancient art of mosaic, creating large-scale, durable artworks for public and ecclesiastical buildings. Mosaic work, with its painstaking assembly of small tesserae to form a larger image, appealed to the Arts and Crafts dedication to labor-intensive, traditional crafts. His mosaics are known for their rich colors, bold designs, and often symbolic content.

Among his most significant mosaic commissions are those for the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill, London. Frederick Horniman, the museum's founder, commissioned Bell to create a large allegorical panel, approximately 32 feet by 10 feet, above the museum's entrance, depicting "Humanity in the House of Circumstance." This impressive work, completed in 1901, showcases Bell's mastery of the medium and his ability to create impactful public art. Other important mosaic works include those for Westminster Cathedral, a major center for the revival of Byzantine-style mosaic in Britain, where he contributed alongside other artists like George Frampton, and for St. Stephen's Hall in the Palace of Westminster. These commissions underscore his reputation as a leading decorative artist of his day.

Stained Glass: Painting with Light

Stained glass was another medium in which Robert Anning Bell made significant contributions. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a renaissance in stained glass art, driven by the Gothic Revival and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Artists like Bell, Christopher Whall, and Henry Holiday moved away from the often overly pictorial and sentimental styles of the mid-Victorian period, seeking to rediscover the true principles of the medieval craft, emphasizing the translucent quality of glass and the importance of leading lines in the design.

Bell designed numerous stained glass windows for churches, public buildings, and private residences. His designs are characterized by their strong draughtsmanship, rich jewel-like colors, and often intricate symbolism. Notable examples of his stained glass work can be found in Westminster Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament, demonstrating his ability to work on a grand scale and within prestigious architectural contexts. He also designed windows for the new Manchester Reference Library and contributed to the decorative schemes of various churches, often working with leading stained glass studios to realize his designs.

Sculpture: The Art of Low Relief

Bell's sculptural work primarily took the form of low-relief panels, often in painted plaster or gesso, a technique reminiscent of Renaissance masters like Donatello and the aforementioned Luca della Robbia. These reliefs frequently depicted allegorical figures, classical scenes, or decorative motifs, and were designed to be integrated into architectural settings or as independent decorative objects. His skill in modeling and his understanding of how light interacts with shallow relief allowed him to create works of subtle beauty and refinement. These pieces often possessed a lyrical, almost painterly quality, blurring the lines between sculpture and painting.

A Respected Educator

Beyond his prolific artistic output, Robert Anning Bell was a highly respected and influential art educator. He held several important teaching positions, shaping a new generation of artists and designers. He served as Professor of Decorative Art at University College, Liverpool (from 1895 to 1899), where he played a key role in developing the art school's curriculum.

Later, he became Professor of Design and, from 1911, Director of the Section of Design and Crafts at the Glasgow School of Art. This was a particularly significant period, as Glasgow was a vibrant center for art and design, with figures like Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the "Glasgow Style" gaining international recognition. Bell's tenure there, though perhaps overshadowed by the more avant-garde work of Mackintosh and his circle (including Mackintosh's wife Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, her sister Frances Macdonald, and James Herbert McNair, who was one of Bell's students), contributed to the school's strong reputation in the decorative arts.

From 1918 to 1924, Bell was Professor of Design at the Royal College of Art in London, one of the most prestigious art institutions in the country. His teaching emphasized a strong grounding in traditional techniques, an understanding of materials, and the importance of good design principles. His influence helped to perpetuate the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement within the formal art education system.

Collaborations and Connections

Throughout his career, Bell collaborated with and was connected to many leading artists and architects of his time. His involvement with the Art Workers' Guild brought him into contact with a wide circle of creative individuals. He worked alongside sculptor Sir George Frampton on various projects, including decorative schemes. Frampton, a key figure in the "New Sculpture" movement and a master of the Guild, was instrumental in promoting the work of artists like Bell.

His teaching role at Glasgow connected him to the circle around Charles Rennie Mackintosh, particularly through his student James Herbert McNair, who, along with Mackintosh and the Macdonald sisters, formed "The Four," central to the development of the Glasgow Style. While Bell's own style was more rooted in English traditions and Renaissance influences than the more stylized and symbolic work of the Glasgow School, his presence there contributed to the rich artistic environment.

Notable Incidents and Curiosities

While Robert Anning Bell's life was primarily dedicated to his art and teaching, a few notable incidents and some curious, though likely unrelated, associations are sometimes mentioned.

One unfortunate event was the loss of his painting The Chase. This work was tragically destroyed in the fire that ravaged the Mackintosh Building at the Glasgow School of Art on May 23, 2013. The loss of any artwork is regrettable, and the destruction of The Chase within such an iconic building, where Bell himself had taught, was a poignant reminder of the fragility of cultural heritage.

It is important to address a point of potential confusion that sometimes arises due to the commonality of names. The provided information mentions "Bell Witch" incidents and a "邪灵娃娃" (evil spirit doll) named Robert receiving apology letters. These are fascinating pieces of folklore but are entirely unrelated to Robert Anning Bell, the British artist. The "Bell Witch" is a famous American folklore tale from the early 19th century in Tennessee, concerning the Bell family of Adams, Tennessee, and has no connection to the London-born artist. Similarly, "Robert the Doll" is another piece of American folklore, a supposedly haunted doll originating from Key West, Florida. These stories, while intriguing, belong to different cultural contexts and should not be conflated with the life or work of Robert Anning Bell, the artist. Such confusions can occasionally arise with historical figures sharing common names.

Legacy and Lasting Influence

Robert Anning Bell passed away on November 27, 1933, leaving behind a rich legacy as a versatile and accomplished artist. His work is represented in numerous public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and various regional galleries throughout the United Kingdom.

His primary contribution lies in his championing of the decorative arts and his embodiment of the Arts and Crafts ethos. He demonstrated that art could be successfully integrated into architecture and everyday objects, enhancing the beauty and quality of life. His mastery across diverse media – from the monumental scale of mosaics and stained glass to the intimate charm of book illustration – showcased his remarkable talent and dedication to craftsmanship.

As an educator, he influenced a generation of students, instilling in them a respect for materials, technique, and the principles of good design. While perhaps not as radical or revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Bell played a crucial role in maintaining and developing high standards of craftsmanship and artistry in a period of significant artistic change. He helped to bridge the gap between the Victorian era and the modern age, adapting traditional forms and techniques to contemporary needs and aesthetics. His work remains a testament to the enduring appeal of beauty, skill, and the harmonious integration of art into the fabric of life, a true scion of the ideals championed by William Morris, John Ruskin, and their followers. His influence can be seen in the continued appreciation for handcrafted design and the revival of traditional artistic techniques.