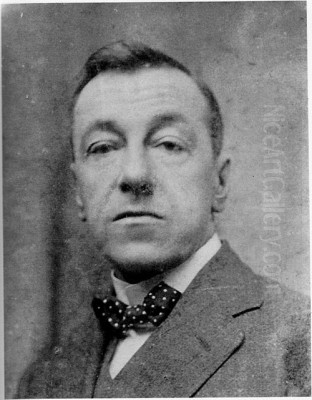

Harold Copping stands as a significant figure in the history of British illustration, particularly renowned for his evocative and widely reproduced depictions of biblical scenes. Active during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, a time often referred to as the "Golden Age of Illustration," Copping (1863-1932) carved a distinct niche for himself. While his name is inextricably linked with religious imagery that shaped the visual understanding of the Bible for millions, his prolific output also encompassed illustrations for classic literature, children's books, and popular periodicals. His work, characterized by its accessible naturalism, meticulous detail, and narrative clarity, resonated deeply with contemporary audiences and continues to hold historical interest today.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Harold Copping was born in London in 1863, into a family with connections to both the literary and artistic worlds. His father worked as a journalist, suggesting an environment where narrative and communication were valued. Perhaps more significantly for his future career, his maternal grandfather was John Skinner Prout (1805-1876), a noted watercolour artist known for his topographical views. This familial artistic lineage likely provided early encouragement and exposure to the visual arts.

Copping's formal artistic training took place at one of London's most prestigious institutions, the Royal Academy Schools. Admission and study here provided a rigorous grounding in academic drawing, painting, and composition, following a curriculum that emphasized traditional skills. His talent was recognized when he won the Landseer Scholarship, a significant award named in honour of the celebrated animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873). This scholarship enabled Copping to further his studies in Paris, then arguably the epicentre of the Western art world, exposing him to different artistic currents and techniques. This combination of solid British academic training and Parisian experience equipped him with the technical proficiency that would underpin his long career. Early reports also mention his commitment to working directly from nature, including plein air (outdoor) sketching, a practice that would inform the realism of his later work.

Emergence as a Versatile Illustrator

Before becoming predominantly known for his religious art, Harold Copping established himself as a versatile and reliable illustrator for the burgeoning print market of the late 19th century. The era saw an explosion in illustrated magazines and books, catering to a growing literate public eager for visual accompaniment to text. Copping contributed illustrations to numerous popular periodicals, demonstrating his ability to adapt to different subjects and formats.

His work appeared in widely read magazines such as the Girl's Own Paper and the Boy's Own Paper, publications aimed at young audiences that often featured adventure stories, educational articles, and moral tales. He also illustrated for magazines with broader appeal, including The Leisure Hour, Little Folks, Pearson's Magazine, The Royal Magazine, The Temple Magazine, and The Windsor Magazine. This work required him to depict a wide range of scenes, from domestic interiors and character studies to more dramatic or adventurous moments, honing his narrative skills.

Beyond periodicals, Copping turned his hand to book illustration, including editions of literary classics. He provided illustrations for works by Charles Dickens, such as A Christmas Carol and David Copperfield. Illustrating Dickens placed him in a lineage that included famous earlier artists like Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz') (1815-1882) and George Cruikshank (1792-1878), although Copping's style reflected the later Victorian taste for greater realism. He also created illustrations for Louisa May Alcott's beloved novel Little Women, showcasing his ability to capture the nuances of character and domestic life. Furthermore, he illustrated various children's books, such as The Story of Hector's Friend and Chigorol and Rhymes, demonstrating a breadth that spanned different genres and audiences early in his career.

The Defining Turn to Religious Illustration

While successful as a general illustrator, Harold Copping's career took a defining turn when he began to work extensively for religious organizations, most notably the Religious Tract Society (RTS) and the London Missionary Society (LMS). These organizations were powerful forces in Victorian and Edwardian Britain, dedicated to spreading Christian literature and supporting missionary activities both domestically and across the British Empire. They recognized the power of images to communicate biblical narratives and religious teachings to a wide audience, including those with limited literacy.

Copping's association with the RTS proved particularly fruitful and enduring. The society commissioned him for numerous projects, valuing his ability to render biblical scenes with clarity, realism, and a sense of earnestness that aligned with their evangelical mission. This wasn't merely commercial work; it placed Copping at the heart of contemporary religious publishing and visual culture. His illustrations became ubiquitous in RTS publications, Sunday school materials, and related contexts.

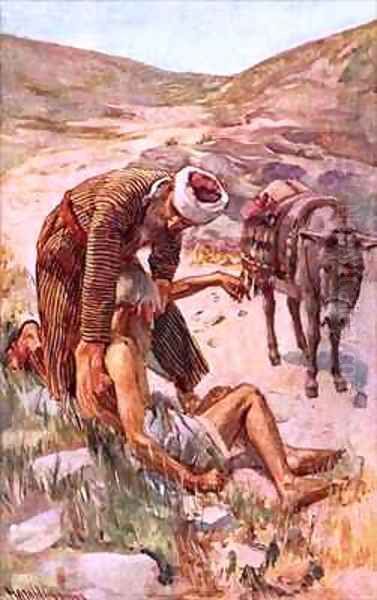

The demand for such imagery was immense. Visual aids were considered essential tools for religious education and missionary work. Copping's illustrations, easily reproducible through modern printing techniques, offered vivid and relatable portrayals of biblical figures and events. They aimed to make the stories accessible and emotionally engaging, moving away from the highly stylized or allegorical representations of earlier religious art towards a more direct, humanized depiction. This shift reflected broader trends in popular religious sentiment that emphasized the personal and relatable aspects of faith.

The Copping Bible and Landmark Religious Works

The pinnacle of Harold Copping's religious illustration work, and the project for which he remains best known, is undoubtedly the series of illustrations commissioned by the Religious Tract Society that became known as the Copping Bible. First published around 1910, this edition featured a significant number of full-colour plates by Copping – sources often cite 64 colour illustrations. The book was an immediate and massive success, becoming a bestseller and cementing Copping's reputation.

One image from this series achieved iconic status: The Hope of the World. This depiction of Jesus surrounded by children from various ethnic backgrounds became one of the most widely recognized and reproduced religious images of the early 20th century. Its appeal lay in its direct emotionalism and its visual representation of a universalist Christian message, aligning perfectly with the missionary outlook of the RTS. The popularity of the Copping Bible illustrations was such that they were frequently reproduced as individual prints, postcards, and lantern slides used by missionaries worldwide for teaching and preaching.

Prior to the Copping Bible, Copping had already undertaken a major commission for the RTS: illustrating a 1903 edition of John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress. For this classic allegory, he produced sixty illustrations. Illustrating Bunyan placed him in dialogue with a long tradition of artists who had tackled the text, including, in a vastly different visionary style, William Blake (1757-1827). Copping's approach, however, was characteristically straightforward and narrative-focused, aiming to bring the allegorical journey to life for a contemporary readership.

His prolific output for the RTS continued with other popular titles, including The Bible Story Book (1923), The Golden Land: The Story of the Holy Land for Children (1911), and My Bible Book (1923). He also created numerous individual paintings and watercolours depicting specific biblical events, such as The Call of Andrew and Peter (1907) and the notable watercolour Christ's Entry into Jerusalem (1914). These works consistently displayed his commitment to clear storytelling and relatable human figures within historically imagined settings.

Artistic Method: The Pursuit of Authenticity

A key aspect of Harold Copping's approach, particularly for his biblical illustrations, was his dedicated pursuit of authenticity. He believed that grounding his depictions in realistic details of place, custom, and appearance would lend them greater power and credibility. This commitment led him to undertake extensive research and travel.

Crucially, Copping made several journeys to Palestine and Egypt. These trips were not mere holidays; they were working expeditions designed to gather firsthand visual information. He sketched landscapes, architectural details, and, importantly, the people he encountered, seeking to capture the atmosphere and specifics of the regions where the biblical events unfolded. This practice aligned him with other contemporary artists, like the French painter James Tissot (1836-1902), who also travelled to the Holy Land to create meticulously researched biblical illustrations. It also echoed the earlier endeavours of Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), who famously journeyed to the Middle East to paint biblical scenes with ethnographic accuracy.

Copping's quest for authenticity extended to his studio practice back in England. He reportedly amassed a collection of costumes and props relevant to the biblical era, allowing him to clothe his models accurately and include convincing details in his compositions. He often used family members, friends, and neighbours as models for his figures, grounding the sacred narratives in familiar human forms. This combination of direct observation from his travels and careful staging in the studio contributed significantly to the believable, almost photographic quality that characterized much of his work and made it so accessible to his audience.

Style, Technique, and Artistic Context

Harold Copping's artistic style can be firmly placed within the tradition of late Victorian and Edwardian naturalism. His primary goal was representational accuracy and narrative clarity, rather than stylistic innovation or personal expression in the manner of the burgeoning modernist movements. He eschewed the radical experiments of Impressionism, exemplified by artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), or the intense subjectivism of Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), who also tackled religious themes but with a profoundly different emotional and stylistic charge.

Copping excelled in watercolour, a medium well-suited to illustration due to its luminosity and relative speed. His handling was precise and detailed, allowing him to render textures, facial expressions, and intricate elements of costume and setting effectively. His compositions were typically well-structured and easy to read, focusing the viewer's attention on the central narrative or emotional core of the scene. There was often a certain literalness in his interpretations; he aimed to depict the biblical accounts as historical events, populated by real people in tangible environments.

Compared to some other illustrators of the "Golden Age," his style might seem less decorative or fantastical. He did not generally employ the sinuous lines and stylized forms of Art Nouveau, nor the whimsical or sometimes grotesque imagination found in the work of contemporaries like Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) or Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), who excelled in illustrating fairy tales and myths. Copping's strength lay in his straightforward, earnest realism, which proved perfectly suited to the demands of religious and popular narrative illustration. His work provided a visual anchor for the text, making stories feel immediate and believable. While earlier masters of religious art like Raphael (1483-1520) or Michelangelo (1475-1564) aimed for idealized grandeur, Copping sought a relatable humanity.

Reception, Legacy, and Collections

Harold Copping's illustrations achieved enormous popularity during his lifetime and for decades afterward. His work for the Religious Tract Society, particularly the Copping Bible images, was reproduced in vast quantities and circulated globally through the society's extensive network. These images became the default visualization of the Bible for generations of Protestant Christians in Britain, the Commonwealth, and America. Their use as lantern slides in missionary presentations further extended their reach and impact, making Copping arguably one of the most widely seen artists of his time, even if his name was not always known.

His professional reputation was strong; he was known as a diligent and skilled craftsman. While his religious works were immensely successful within their intended context, some modern viewers might find the depictions somewhat literal, sentimental, or occasionally reflecting the cultural assumptions of his era. For instance, a painting held by the Wellcome Collection in London, depicting a Black African kneeling before a white missionary, is viewed today through the lens of colonial history and power dynamics. However, within their original context, his works were generally seen as respectful and effective aids to faith.

Interestingly, despite the vast reproduction of his work, it seems Copping often sold the copyright to his illustrations outright to the publishers, particularly the RTS. While this provided him with steady income, it meant he likely did not receive ongoing royalties, which, given the enduring popularity of his images, could have amounted to a considerable fortune.

Harold Copping died in 1932. His legacy resides primarily in the enduring impact of his biblical illustrations. While perhaps not celebrated within the canons of high art, his work played a significant role in popular religious culture and the history of illustration. His influence can be seen in subsequent religious illustrators who adopted a similar naturalistic and accessible style, such as the American artist Warner Sallman (1892-1968), whose Head of Christ achieved similar iconic status.

Today, original works by Harold Copping are held in several public collections. The Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. holds significant examples, including watercolours donated from the RTS archives via intermediate owners, such as the aforementioned Christ's Entry into Jerusalem. The Wellcome Collection in London holds the missionary-themed painting. Illustrations produced for various publications are also found in collections like the Spencer Collection of illustrated books and manuscripts, housed at Towneley Hall Art Gallery & Museum in Burnley. These collections preserve examples of his contribution to both religious and secular illustration.

Conclusion: An Enduring Visual Legacy

Harold Copping occupies a unique place in British art history. As a master illustrator working during a period of high demand for printed images, he demonstrated exceptional technical skill, particularly in watercolour, and a remarkable capacity for narrative clarity. While his contributions to the illustration of classic literature and children's books are noteworthy, his enduring fame rests on his vast output of biblical scenes for the Religious Tract Society.

Through works like the Copping Bible and iconic images such as The Hope of the World, he profoundly shaped the visual imagination of millions, providing accessible, realistic, and emotionally resonant depictions of sacred stories. His commitment to authenticity, evidenced by his travels and research, lent credibility to his work. Although artistic tastes have evolved, and some aspects of his work are viewed differently today, Harold Copping's illustrations remain a significant part of the cultural and religious heritage of the early 20th century, testament to the power of images to communicate faith and story across generations. His prolific career exemplifies the reach and impact of popular illustration during its golden age.