Elliot Daingerfield stands as a significant figure in American art, a painter whose canvases resonate with a profound sense of mood, mystery, and an almost spiritual connection to the natural world. Active during a transformative period in American art history, from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, Daingerfield carved a unique path, blending influences from European traditions with a distinctly American sensibility. His landscapes, often imbued with a soft, Tonalist light, and his deeply felt religious compositions, reveal an artist constantly seeking to express the intangible and the sublime.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on February 26, 1859, in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), Elliot Daingerfield's early life was soon touched by the momentous events of his time. His father, Captain John Elliot Daingerfield, was a Confederate officer. Shortly after Elliot's birth, the family relocated to Fayetteville, North Carolina, where Captain Daingerfield was tasked with managing the arsenal. The American Civil War cast a long shadow over young Elliot's childhood. He witnessed firsthand the turmoil and devastation of the conflict, including the family's experiences when Union General William T. Sherman's troops moved through Fayetteville. These early impressions of upheaval and the dramatic landscapes of the South would subtly inform his artistic vision later in life.

Even from a young age, Daingerfield exhibited a keen interest in art. His formal education in Fayetteville was supplemented by a burgeoning passion for drawing and painting. He was largely self-taught in these initial years, absorbing what he could from available resources and observing the world around him with an artist's eye. The rich natural beauty of North Carolina, with its rolling hills, dense forests, and atmospheric conditions, undoubtedly provided early inspiration. This connection to the Southern landscape would remain a recurring theme throughout his career, even as he sought training and established his reputation further north.

Artistic Training and the New York Scene

Recognizing the need for formal instruction and a more stimulating artistic environment, Daingerfield made the pivotal decision to move to New York City in 1880, at the age of twenty-one. This was a bold step for a young man from the South, but New York was rapidly becoming the epicenter of American art, offering unparalleled opportunities for study and exposure. He enrolled at the prestigious Art Students League, a vital institution known for its progressive teaching methods and its roster of influential instructors and alumni.

At the League, Daingerfield immersed himself in his studies, honing his technical skills in drawing and painting. It was during this period that he also began to work as an assistant to the artist Walter Satterlee. Satterlee (1844-1908), a figure painter and illustrator, provided Daingerfield with practical experience and mentorship. Working in Satterlee's studio, Daingerfield would have gained insights into the professional life of an artist, from studio practices to the intricacies of the art market. This apprenticeship was crucial in bridging the gap between academic study and the realities of a career in art.

New York also exposed Daingerfield to a vibrant community of artists and a diverse range of artistic styles. He frequented galleries, exhibitions, and studios, absorbing the prevailing trends and engaging in discussions about art. This immersion was critical for his development, allowing him to see beyond regional confines and to begin formulating his own unique artistic voice. The city's energy and its role as a cultural melting pot provided a stark contrast to his Southern upbringing, broadening his perspectives and ambitions.

The Profound Influence of George Inness

A defining moment in Elliot Daingerfield's early career was his encounter and subsequent friendship with the renowned American landscape painter George Inness (1825-1894). In 1884, Daingerfield took a studio in the Holbein Studios building, the same building where Inness, a towering figure in American landscape painting, also worked. This proximity led to a close association that would profoundly shape Daingerfield's artistic philosophy and technique.

Inness, known for his deeply spiritual and evocative landscapes, became a mentor to the younger artist. He was a leading proponent of a style that would later be closely associated with Tonalism, emphasizing mood, atmosphere, and a subjective response to nature over literal representation. Daingerfield was a receptive student, drawn to Inness's poetic interpretations of the landscape and his sophisticated use of color and light. Inness taught Daingerfield specific techniques, such as the use of thin glazes of paint and varnish to achieve luminous, atmospheric effects and rich, deep tones. This method allowed for a subtlety and depth of color that became a hallmark of Daingerfield's mature style.

Perhaps one of the most significant lessons Daingerfield learned from Inness was the practice of painting from memory. Inness encouraged him to absorb a scene in nature, to internalize its essential qualities, and then to recreate it in the studio, filtered through his own emotional and spiritual understanding. This approach freed the artist from the constraints of direct observation, allowing for a more personal and imaginative interpretation of the landscape. It enabled Daingerfield to imbue his scenes with a sense of mystery and introspection, qualities that resonated with the Symbolist tendencies emerging in art at the time. The impact of Inness was not merely technical; it was also deeply philosophical, instilling in Daingerfield a belief in the spiritual power of art and the artist's role as an interpreter of nature's deeper meanings.

Artistic Style: Tonalism, Symbolism, and a Lyrical Vision

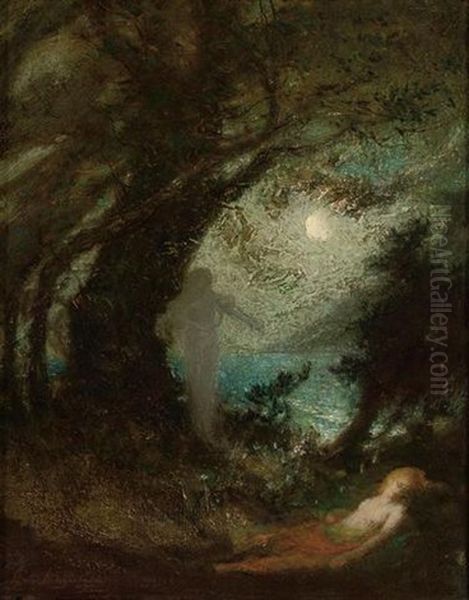

Elliot Daingerfield's artistic style is most often categorized within the Tonalist movement, an American artistic style that emerged in the 1880s and flourished into the early 20th century. Tonalism, as practiced by artists like Inness, Dwight William Tryon (1849-1925), and John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902) in his earlier phases, was characterized by soft, diffused light, a limited palette of harmonious colors (often greens, browns, grays, and blues), and an emphasis on mood and atmosphere. Daingerfield excelled in this mode, creating landscapes that were not merely depictions of place but evocations of feeling—often melancholic, serene, or mystical.

His work also shows a strong affinity with the broader Symbolist movement, which sought to express ideas and emotions through suggestive imagery rather than direct representation. This is particularly evident in his religious paintings and in landscapes that seem to hint at unseen presences or transcendent realities. Figures, when they appear, are often enigmatic or allegorical, contributing to the overall sense of mystery. The influence of the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) and Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867), can also be discerned in Daingerfield's reverence for nature and his poetic treatment of rural scenes. Like the Barbizon painters, he found beauty and spiritual solace in the everyday landscape.

While primarily a Tonalist, Daingerfield's style was not static. His exposure to European art, including Impressionism, during his travels abroad, subtly informed his work, perhaps in a lighter palette at times or a more broken brushstroke, but he never fully embraced the Impressionist focus on fleeting optical effects. Instead, he integrated these influences into his fundamentally romantic and spiritual vision. There are also occasional references to the detailed naturalism and literary themes of the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly in the way he could render certain elements with precision while still maintaining an overall atmospheric haze. Artists like Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) and Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919), with their highly personal and often visionary landscapes, were also kindred spirits, sharing Daingerfield's inclination towards introspection and poetic expression.

Masterpieces and Major Themes: Landscapes and Religious Works

Elliot Daingerfield's oeuvre is rich with memorable works that showcase his distinctive style and thematic concerns. His landscapes often depict the twilight hours, misty mornings, or moonlit nights, times when the veil between the seen and unseen seems thinnest. Works like Moon Rising over Fog Clouds (watercolor, Metropolitan Museum of Art) exemplify his mastery of atmosphere and light, capturing the ethereal beauty of nature with a delicate touch. Midnight Moon (oil, Luce Visible Storage and Study Center) is another example, where the nocturnal scene is imbued with a quiet, contemplative mood.

One of his most ambitious and celebrated achievements was the commission to paint murals for the Lady Chapel of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin in New York City, completed in the early 1900s (specifically between 1902 and 1907). These large-scale religious works, including scenes like "The Epiphany" and "The Magnificat," demonstrate his ability to handle complex compositions and to convey profound spiritual themes. The murals are characterized by their rich, jewel-like colors, their mystical atmosphere, and their blend of traditional iconography with Daingerfield's personal, romantic sensibility. They stand as a testament to his deep Christian faith and his skill in translating spiritual narratives into compelling visual form.

Daingerfield was also captivated by the grandeur of the American West. He made several trips to the Grand Canyon, and these experiences resulted in powerful paintings such as The Genius of the Canyon (1913). In these works, he sought to capture not just the physical immensity of the landscape but also its sublime, almost overwhelming spiritual presence. He approached the Grand Canyon with a sense of awe, translating its dramatic forms and atmospheric effects into canvases that convey both its majesty and its mystery. Other notable landscape paintings include Return from the Farm, where his skillful use of color harmonies—balancing reds, greens, and blues in the foliage—creates a visually satisfying and emotionally resonant scene.

His landscapes of North Carolina, particularly those painted around his later home in Blowing Rock, are among his most personal and evocative. These works often feature the rolling hills, misty valleys, and dramatic skies of the Blue Ridge Mountains, rendered with a deep affection and understanding of the region's unique character. Throughout his career, whether depicting the intimate corners of a forest or the vast expanse of a canyon, Daingerfield consistently sought to reveal the spiritual essence he perceived within the natural world.

European Travels and Broadening Horizons

Like many American artists of his generation, Elliot Daingerfield recognized the importance of experiencing European art firsthand. He made several trips to Europe, with documented visits between 1897 and 1924. These journeys provided him with opportunities to study the Old Masters, to see the latest developments in contemporary European art, and to immerse himself in different cultural environments. Italy, with its rich artistic heritage and picturesque landscapes, held a particular allure. His visits to Venice, for example, likely reinforced his appreciation for atmospheric effects and the interplay of light and water, elements that were already central to his Tonalist aesthetic.

While Daingerfield's core artistic vision remained consistent, his European travels undoubtedly broadened his technical repertoire and enriched his understanding of art history. He absorbed influences from various sources, but always assimilated them into his own distinctive style. He was not one to slavishly imitate European trends; rather, he selectively incorporated elements that resonated with his existing artistic concerns. For instance, the romanticism inherent in much European landscape painting, from the Barbizon School to artists like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), would have found a sympathetic echo in Daingerfield's own sensibilities.

The exposure to different artistic traditions and the experience of new landscapes likely deepened his appreciation for the universal aspects of art and nature. These travels contributed to the sophistication and maturity of his later work, allowing him to approach his familiar themes with renewed insight and a more refined technique. His ability to synthesize these diverse influences while maintaining a strong personal voice is a testament to his artistic integrity and vision.

Later Life in Blowing Rock, Teaching, and Legacy

In his later years, Elliot Daingerfield increasingly spent time in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, a picturesque town in the Blue Ridge Mountains. He had first visited the area in the 1880s and was captivated by its scenic beauty. He eventually established a summer home and studio there, which he named "Westglow," built in 1916. He later acquired or built two other studios in the area, "Windwood" and "Childlong." These mountain retreats became important centers for his artistic production, providing him with a direct connection to the landscapes he loved to paint. The serene environment of Blowing Rock offered a contrast to the bustle of New York and allowed him to focus on his work in a setting that was both inspiring and restorative.

Daingerfield was not only a prolific painter but also a respected teacher and writer. He taught at the Art Students League in New York and at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art and Design), sharing his knowledge and experience with a new generation of artists. His teaching would have emphasized the principles he had learned from Inness and developed through his own practice, particularly the importance of mood, atmosphere, and personal expression.

He also contributed to the art discourse of his time through his writings. He authored articles on artists he admired, most notably a monograph on George Inness, published in 1911, which provided valuable insights into Inness's life and work. He also wrote about other artists, including Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Albert Blakelock, demonstrating his engagement with the broader American art scene and his desire to promote an appreciation for their unique contributions. His writings, like his paintings, often reflected his belief in the spiritual dimension of art.

Elliot Daingerfield received numerous accolades during his lifetime, including the Thomas B. Clarke Prize from the National Academy of Design in 1902, an institution to which he was elected an Associate in 1902 and a full Academician in 1906. His work was widely exhibited and collected by major museums and private collectors. He passed away in New York City on October 22, 1932, at the age of 73, leaving behind a significant body of work that continues to be admired for its beauty, sensitivity, and spiritual depth.

Connections and Contemporaries in American Art

Elliot Daingerfield's career unfolded during a dynamic period in American art, and he was connected, either through direct association or shared artistic concerns, with many prominent figures. His most significant relationship was, of course, with George Inness, whose mentorship was foundational. His early teacher, Walter Satterlee, provided initial professional guidance.

Within the Tonalist movement, Daingerfield's work shares affinities with that of Dwight William Tryon, known for his delicate, poetic landscapes, and John Francis Murphy (1853-1921), whose works also emphasized subtle atmospheric effects. The visionary and deeply personal art of Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Albert Blakelock resonated with Daingerfield's own mystical inclinations, and he wrote appreciatively of their work. Though their styles were distinct, they shared a romantic, introspective approach to landscape painting that set them apart from the more objective naturalism or brighter Impressionism of some of their contemporaries.

Other important landscape painters of the era whose work provides context for Daingerfield's include Alexander Helwig Wyant (1836-1892) and Homer Dodge Martin (1836-1897), both of whom, like Inness, were influenced by the Barbizon School and contributed to the development of a distinctly American landscape tradition. While American Impressionists like Childe Hassam (1859-1935) and J. Alden Weir (1852-1919) were exploring the effects of light and color in a different manner, their presence highlights the diverse artistic currents of the time. Daingerfield's commitment to a more subjective, spiritual interpretation of nature positioned him as a key figure in the Tonalist and Symbolist-leaning wing of American art. Even the figure paintings of Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938), with their refined aesthetics and enigmatic female figures in Tonalist interiors or landscapes, share a certain poetic sensibility with Daingerfield's art.

Daingerfield's Enduring Place in American Art History

Elliot Daingerfield occupies an important place in the narrative of American art as a leading exponent of Tonalism and as an artist who successfully bridged late 19th-century romanticism with early 20th-century sensibilities. He infused the American landscape tradition with a profound sense of spirituality and poetic mystery, creating works that invite contemplation and evoke deep emotional responses. His ability to synthesize influences from the Barbizon School, the legacy of George Inness, and broader Symbolist currents into a highly personal style is a testament to his artistic vision.

His religious paintings, particularly the murals for the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, represent a significant contribution to American religious art, a field often overshadowed by landscape and portraiture during this period. These works demonstrate his capacity for large-scale, thematically complex compositions and his commitment to expressing his faith through his art.

Daingerfield's dedication to the landscapes of both his native South and the majestic American West, rendered with his characteristic atmospheric depth, ensured his popularity during his lifetime and has contributed to his lasting appeal. He was an artist who looked beyond the surface of reality to capture the underlying spirit of place and the ineffable qualities of light and mood. His work serves as a poignant reminder of a period in American art when painters sought to convey not just what the eye sees, but what the soul feels.

Conclusion: The Luminous Legacy of Elliot Daingerfield

Elliot Daingerfield's legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his own lyrical and spiritual vision throughout a long and productive career. His paintings, whether intimate woodland scenes, expansive Western vistas, or profound religious allegories, are united by their evocative power and their masterful handling of light, color, and atmosphere. He was a painter of mood, a poet in pigment, whose works continue to resonate with viewers today, offering moments of quiet beauty and spiritual reflection. As an artist who deeply understood the expressive potential of the American landscape and who sought to convey its spiritual essence, Elliot Daingerfield remains a cherished and important figure in the rich tapestry of American art. His contributions as a painter, teacher, and writer have secured his place as a significant voice from an era of profound artistic exploration and achievement.