Julius Josephus Gaspard Starck, a French painter active during the vibrant artistic period of the 19th century, carved out a niche for himself with his depictions of genre scenes and, notably, his contributions to the Orientalist movement. Born in 1814 and passing away in 1884, Starck's life and career spanned a transformative era in European art, witnessing the ebb and flow of Neoclassicism, the surge of Romanticism, the rise of Realism, and the widespread fascination with the "Orient." While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries, Starck's work offers valuable insights into the artistic tastes and cultural preoccupations of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Julius Josephus Gaspard Starck was born in Riedseltz, a commune in the Bas-Rhin department in the historical region of Alsace, which is now part of the Grand Est region of northeastern France, in 1814. This region, with its unique cultural blend due to its proximity to Germany, may have offered early, albeit indirect, exposure to diverse European artistic traditions. However, detailed information about his early childhood and initial artistic inclinations remains somewhat scarce in readily accessible records.

What is more clearly documented is his formal artistic training, which placed him under the tutelage of two significant figures in the art world of the time: François-Joseph Navez and Horace Vernet. This tutelage was crucial in shaping his technical skills and artistic outlook. Navez, a Belgian Neoclassical painter, would have instilled in Starck a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the classical ideals of form and clarity. Vernet, on the other hand, was renowned for his large-scale battle scenes, historical paintings, and, significantly, his Orientalist works, which likely ignited or fueled Starck's own interest in these exotic themes.

The Influence of His Masters

François-Joseph Navez (1787–1869) was a prominent Belgian painter who studied in Paris under the great Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David. Navez became a leading figure in Belgian Neoclassicism, known for his portraits and historical scenes. His teaching would have emphasized rigorous academic discipline, anatomical precision, and a balanced, harmonious composition. Starck's exposure to Navez's methods would have provided him with the essential technical skills required for detailed figure painting and complex genre scenes. Artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a contemporary of Navez and fellow pupil of David, further exemplified the Neoclassical pursuit of idealized form and linear purity that would have been part of the artistic discourse during Starck's formative years.

Horace Vernet (1789–1863), in contrast, represented a more dynamic and Romantic sensibility, though he also possessed a strong academic grounding. Vernet was immensely popular for his depictions of military campaigns, particularly those of Napoleon, and later, the French conquest of Algeria. His travels to North Africa provided him with firsthand material for his Orientalist paintings, which were celebrated for their ethnographic detail and dramatic flair. Under Vernet, Starck would have been exposed to a broader range of subject matter, a more painterly technique, and the burgeoning European fascination with the cultures of the Middle East and North Africa. Vernet's influence is particularly pertinent to Starck's later specialization in Orientalist themes. Other artists like Théodore Géricault, a close contemporary of Vernet, also explored dramatic historical and contemporary events with a similar Romantic energy.

Embracing Orientalism: Visions of the East

The 19th century witnessed a surge in "Orientalism," an artistic and cultural phenomenon where Western artists depicted subjects derived from North Africa, the Middle East (often referred to as the Levant), and Asia. This interest was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and a Romantic yearning for the exotic, the picturesque, and the supposedly "untouched" civilizations. Starck became a participant in this movement, contributing works that catered to the European public's appetite for scenes of distant lands.

His paintings often focused on "typical scenes and figures," suggesting an interest in capturing the daily life, customs, and character of the cultures he depicted. While it's not definitively clear from the provided information the extent of Starck's personal travels to these regions, many Orientalist painters, following the example of artists like Eugène Delacroix or Jean-Léon Gérôme, did undertake such journeys to gather authentic material. Others relied on travelogues, existing imagery, and studio props.

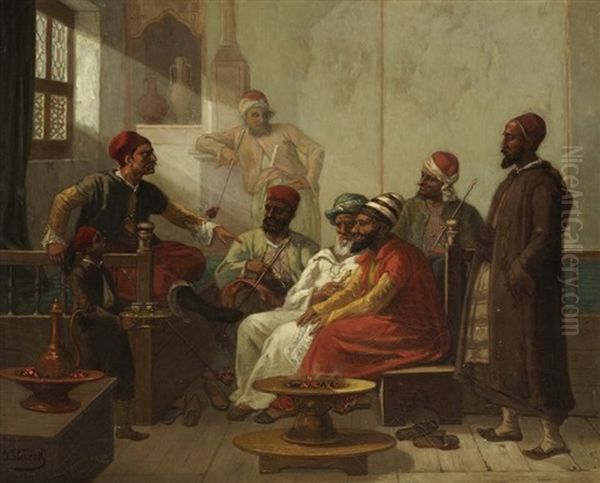

One of Starck’s noted works in this vein is Scène de café en Turquie (Turkish Coffee House Scene). Coffee houses in the Ottoman Empire were important social hubs, places for conversation, storytelling, and relaxation. Such a scene would have allowed Starck to depict varied figures in traditional attire, architectural details, and cultural practices like the consumption of coffee or the smoking of narghiles (water pipes), all elements that appealed to the Western gaze. Artists like John Frederick Lewis, a British Orientalist, meticulously detailed similar interior scenes with a focus on light and texture.

Another significant Orientalist piece by Starck is Le Fumeur de Narghile (The Narghile Smoker). The narghile, or hookah, was a common motif in Orientalist art, often symbolizing leisure, contemplation, and an exotic way of life. This oil painting, sometimes dated to 1887 (though this date is problematic given his death in 1884, suggesting either a posthumous exhibition, a misattribution, or an error in dating records), would likely have focused on a single figure or a small group engaged in this pastime, allowing for detailed rendering of costume, the ornate narghile itself, and a suggestive atmosphere. The theme resonates with works by painters such as Rudolf Ernst or Ludwig Deutsch, who specialized in highly detailed and polished Orientalist genre scenes.

The Scribe, dated in some sources to 1891 (again, a date that conflicts with his established death year), is another key example of Starck's Orientalist output. Scribes held important roles in Ottoman society, particularly in a culture with varying literacy rates, assisting with correspondence, legal documents, and religious texts. They were often found in public spaces, such as near mosques or government buildings. Starck's depiction would likely have shown a scribe at work, perhaps surrounded by the tools of his trade, offering a glimpse into a specific profession and social dynamic. This painting was notably included in an exhibition catalog for the Pera Museum in Istanbul, indicating its relevance to the visual culture of the Ottoman world, or at least Western perceptions of it. The Turkish painter Osman Hamdi Bey, a contemporary who studied in Paris, offered an insider's perspective on similar Ottoman subjects, providing a valuable counterpoint to Western Orientalist views.

These works collectively showcase Starck's engagement with Orientalist tropes: the depiction of daily life, specific cultural practices, and figures in traditional settings. His style likely balanced the academic precision learned from Navez with the more vibrant and thematic approach of Vernet.

Historical Scenes and Royal Connections

Beyond his Orientalist works, Starck also engaged with historical subjects, a genre highly respected in the academic tradition. A notable example is Koningin Louisa Maria ontvangt een ring in Saint-Hubert (Queen Louise-Marie receives a ring in Saint-Hubert), painted in 1862. This work depicts Louise-Marie of Orléans (1812–1850), the first Queen of the Belgians as the wife of King Leopold I. The scene, set in Saint-Hubert (a town in the Belgian Ardennes known for its basilica), likely commemorates a specific historical or ceremonial event.

The creation of such a painting suggests a connection to Belgian circles, perhaps facilitated by his training with Navez, a leading Belgian artist. The work would have required careful attention to portraiture, historical costume, and the depiction of a formal royal event. This painting is held in the Royal Collection of Belgium in Brussels, underscoring its significance. Historical painters like Paul Delaroche in France were renowned for their dramatic and meticulously researched depictions of historical events, a tradition Starck's work would align with. Belgian contemporaries like Gustave Wappers or Nicaise De Keyser also excelled in large-scale historical and nationalistic paintings.

The choice of subject and its execution would have aimed to convey dignity, historical importance, and perhaps a sense of national identity for the relatively new Belgian monarchy. The detailed rendering of attire in such a piece is also noteworthy, as evidenced by its inclusion in studies related to the Queen's wardrobe, such as "De Garderobe van Louise-Marie van Orléans."

Artistic Style and Milieu

Based on his teachers and the nature of his subjects, Starck's artistic style can be inferred as one that combined academic precision with a sensitivity to narrative and exotic detail. His figures were likely well-drawn, his compositions carefully arranged, and his rendering of textures, costumes, and settings meticulous. This approach would have been well-suited to both the detailed requirements of Orientalist genre scenes and the formal demands of historical painting.

He operated within a 19th-century European art world dominated by Salons (official art exhibitions) and academies. Success often depended on critical reception at these Salons and the acquisition of patrons, whether private collectors or state institutions. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, a master of both Orientalist and historical subjects, achieved immense fame and influence through this system. While Starck may not have reached Gérôme's level of celebrity, his ability to produce works like the portrait of Queen Louise-Marie and his Orientalist scenes indicates a degree of professional success and recognition.

The art market for Orientalist paintings was robust throughout much of the 19th century. Collectors were eager for these windows into seemingly exotic worlds, and artists who could provide vivid and detailed depictions found a ready audience. Starck's contribution to this genre places him among a multitude of painters, including Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, Eugène Fromentin, and many others who explored similar themes.

Later Life and Legacy

Julius Josephus Gaspard Starck passed away in Joinville, a commune in the Haute-Marne department of northeastern France, in 1884. Information regarding his later career, specific exhibitions beyond what has been mentioned, or any students he might have taught is not extensively detailed in the provided summaries.

His legacy today is primarily that of a skilled 19th-century painter who adeptly navigated popular genres of his time. His Orientalist works contribute to the vast corpus of imagery that shaped Western perceptions of the East, a complex legacy that art historians continue to analyze and debate, particularly in light of post-colonial studies and critiques of Orientalism, such as those famously articulated by Edward Said.

While no specific controversies or major anecdotal events concerning Starck's life are highlighted in the available information, his career appears to be one of steady professional output. He does not seem to be directly associated with any specific avant-garde movements that challenged academic norms, but rather worked within established, popular genres.

His paintings, such as Koningin Louisa Maria ontvangt een ring in Saint-Hubert in the Royal Collection of Belgium, serve as tangible records of his artistic skill and the cultural currents of his era. The inclusion of The Scribe in a Pera Museum context suggests a lasting interest in his Orientalist depictions. Other works, like Scène de café en Turquie and Le Fumeur de Narghile, further define his contribution to this genre.

Academic research specifically dedicated to Starck as a monograph subject appears limited. He is more often mentioned in the context of broader studies on Orientalism, 19th-century genre painting, or in relation to specific collections that hold his work. This is not uncommon for artists who, while proficient and successful in their time, did not achieve the very highest echelons of fame occupied by figures like Delacroix or Ingres.

Conclusion: A Painter of His Time

Julius Josephus Gaspard Starck (1814–1884) remains a representative figure of 19th-century European art. Trained by notable masters François-Joseph Navez and Horace Vernet, he developed a skill set that allowed him to engage effectively with both historical painting and the immensely popular genre of Orientalism. His works, characterized by attention to detail and a focus on genre scenes and figures, particularly those set in imagined or observed "Oriental" locales, catered to the tastes and curiosities of his contemporaries.

His depictions of Turkish coffee houses, narghile smokers, and scribes contributed to the visual vocabulary of Orientalism, while his historical paintings, such as the scene involving Queen Louise-Marie of Belgium, demonstrate his capacity for formal, commemorative art. Though not a revolutionary figure, Starck's oeuvre provides a valuable window into the artistic practices and cultural preoccupations of the 19th century. His paintings are part of a broader artistic conversation, standing alongside the works of more famous Orientalists like Gérôme, Delacroix, and Fromentin, as well as historical painters such as Delaroche and Belgian artists like Leys or Gallait. The study of artists like Starck enriches our understanding of the diverse artistic landscape of an era that continues to fascinate and inform. His works in collections and their occasional appearance in exhibitions ensure that his contribution, though perhaps modest in the grand sweep of art history, is not entirely forgotten.