Charles Willson Peale stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of early American culture. Born in 1741 in St. Paul's Parish, Queen Anne's County, Maryland, and living until 1827, his life spanned a transformative period in American history, witnessing the transition from colonial status to the establishment of a new republic. Peale was far more than just a painter; he embodied the Enlightenment ideal of the polymath – a skilled artist, a dedicated soldier, an innovative inventor, a pioneering scientist, and the founder of one of America's first public museums. His boundless energy, insatiable curiosity, and unwavering belief in the power of knowledge and art left an indelible mark on the nation's identity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Peale's path to becoming one of America's foremost artists was unconventional. His initial trade was that of a saddler, a craft he learned in Annapolis. However, his involvement with the Sons of Liberty and subsequent financial difficulties, exacerbated by Loyalist creditors, forced him to flee Annapolis around 1764. This period of adversity proved pivotal. Having already dabbled in various crafts, including watchmaking and silversmithing, Peale turned his attention increasingly towards painting, a field where he showed natural aptitude despite limited formal training initially.

His early artistic efforts caught the attention of prominent figures. He received rudimentary instruction from John Hesselius in Maryland. Recognizing his potential, a group of patrons, including the lawyer John Beale Bordley, funded Peale's journey to London in 1767. This was a critical step, allowing him to study under the acclaimed American expatriate painter Benjamin West. London exposed Peale to the mainstream of European art, particularly the prevailing Neoclassical style, and allowed him to hone his technical skills. He also encountered the work of other leading artists, including the celebrated portraitist John Singleton Copley, whose American works Peale had already admired and whose detailed realism likely resonated with Peale's own inclinations.

The Portraitist of the Revolution

Upon returning to America in 1769, Peale settled first in Annapolis and later, more permanently, in Philadelphia, which was rapidly becoming the cultural and political heart of the colonies. He arrived at a moment of escalating tension between the colonies and Great Britain, and his skills as a portraitist were soon in high demand. Peale became the de facto painter of the American Revolution, capturing the likenesses of the key figures shaping the new nation.

His portrait style, influenced by his time with West but retaining a distinct American directness, was characterized by solid draftsmanship, clear and even lighting, relatively simple compositions, strong outlines, and often plain backgrounds that focused attention on the sitter. While capable of capturing finery and status, his work often possessed an unpretentious quality, a republican sensibility that suited his subjects and the times. He aimed for truthful representation, a "likeness" that conveyed not just physical appearance but also a sense of the individual's character and role.

Peale painted numerous portraits of George Washington, perhaps more from life than any other artist. His earliest depiction, commissioned by the Mount Vernon council in 1772, shows Washington as a colonel in the Virginia Regiment. One of his most famous Washington portraits is George Washington at Princeton (1779), commissioned by the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. This full-length portrait commemorates the victory at the Battle of Princeton and depicts Washington in a moment of calm command, leaning on a cannon, the captured Hessian flags visible. The painting, with its details like the blue sash (worn by Washington as commander-in-chief) and elegant sword, exemplifies Peale's ability to combine accurate likeness with symbolic representation of leadership and victory.

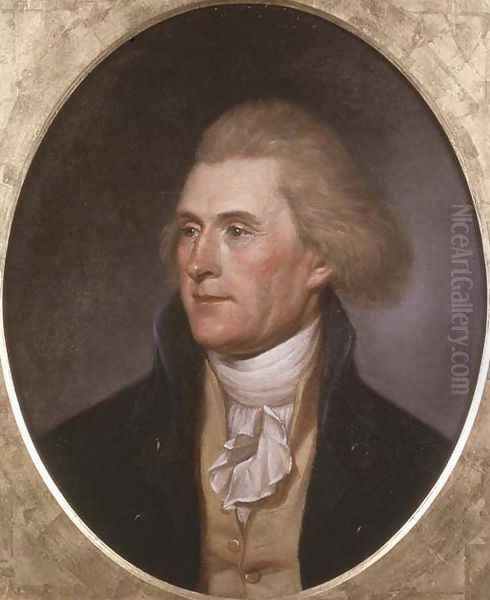

Beyond Washington, Peale's gallery of revolutionary heroes included Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, Nathanael Greene, Horatio Gates, the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron von Steuben, and countless others – soldiers, statesmen, scientists, and thinkers who defined the era. His output was prodigious; estimates suggest he painted over a thousand portraits during his lifetime, including oil paintings and miniatures. These works collectively form an invaluable visual record of the founding generation.

Master of Illusion: The Staircase Group

While renowned for his portraits of public figures, one of Peale's most celebrated and intriguing works features his own family: The Staircase Group (1795). This life-size double portrait depicts his sons, Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay Peale I (who died young), ascending a winding staircase. The painting is a masterpiece of trompe l'oeil, or "fool the eye," illusionism.

Peale originally exhibited the painting within an actual doorframe, complete with a real step projecting out at the bottom. The effect was startlingly realistic, designed to trick viewers into believing they were seeing the actual boys on a staircase. According to anecdote, even George Washington was momentarily fooled by the illusion. The work showcases Peale's technical virtuosity, his interest in perception and illusion, and perhaps a playful aspect of his personality. It also serves as a testament to his deep involvement with his family, whom he actively trained in the arts and sciences. The Staircase Group remains an iconic image in American art history, admired for both its technical skill and its intimate portrayal of familial connection.

Beyond Portraiture: Diverse Artistic Pursuits

Although portraiture formed the core of his artistic career and provided his primary income, Peale's artistic interests were broader. He was a skilled miniaturist, producing nearly 300 miniature portraits. These small, intimate works required meticulous detail and a different technical approach than large-scale oil paintings. Miniatures were popular personal keepsakes, often exchanged between loved ones or carried during travels.

Peale also painted landscapes, though fewer in number. These often depicted scenes around Philadelphia or documented specific locations, sometimes incorporating elements related to natural history or historical events. His historical paintings, though relatively few, tackled significant moments, such as the Exhumation of the Mastodon (discussed later). He also produced a small number of still life paintings, a genre that would become particularly important for his son Raphaelle and his brother James. His versatility underscores his restless energy and wide-ranging curiosity.

The Peale Museum: A Vision of Art and Science

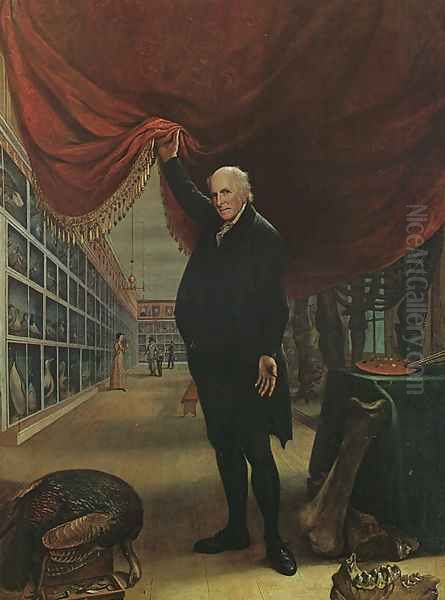

Perhaps Peale's most ambitious and unique contribution was the creation of his museum in Philadelphia. Founded in 1784, initially in his home, it moved to Philosophical Hall in 1794 and later occupied the upper floor of Independence Hall from 1802 to 1827. This institution, often called the Philadelphia Museum or Peale's American Museum, was groundbreaking. It was not merely an art gallery but an embodiment of Peale's Enlightenment belief in the unity of knowledge and the importance of public education.

Peale envisioned his museum as a "world in miniature," a "Book of Nature" and a "School of Wisdom" accessible to all citizens. Its collections were remarkably diverse. One major component was Peale's portrait gallery of Revolutionary heroes and other distinguished individuals, preserving the likenesses of those who had shaped the nation. This served a patriotic and didactic purpose, offering visual exemplars for the public.

Equally important was the natural history collection. Peale was an avid naturalist and taxidermist. He developed innovative methods for preserving and displaying animals in realistic poses and settings, often against painted backdrops depicting their natural habitats. This approach was revolutionary for its time, moving beyond simple cabinets of curiosities towards more engaging and educational dioramas. The museum housed extensive collections of American birds, mammals, insects, minerals, and fossils.

Peale's museum was intended to classify and display specimens according to scientific principles, particularly the Linnaean system of classification. He saw the natural world as a source of wonder, rational order, and divine design, and he wanted to share this understanding with the public. The museum became a major center for natural history study in the United States, attracting scholars and contributing to scientific knowledge.

The Mastodon Adventure

One of the museum's most famous exhibits stemmed from Peale's fascination with paleontology. In 1801, hearing reports of large fossil bones discovered on farms in upstate New York, Peale organized and financed an expedition to excavate them. This was a significant undertaking, involving complex logistics and engineering challenges, including the need to drain water from the marl pits where the bones were found. Peale designed a large treadwheel mechanism, powered by people walking inside it, to operate a bucket chain for drainage – an endeavor he later documented in his painting The Exhumation of the Mastodon (1806-1808).

The expedition successfully recovered two nearly complete mastodon skeletons. Peale meticulously cleaned, repaired, and assembled the bones, creating the first mounted skeletons of these extinct giants for public display. The "Mammoth" skeletons, as they were popularly known, became star attractions at his museum, drawing huge crowds and sparking widespread public interest in America's prehistoric past. This achievement cemented Peale's reputation as both a showman and a serious contributor to natural science. It highlighted the museum's role in bringing scientific discovery directly to the people.

Inventor and Innovator

Peale's practical ingenuity extended beyond museum display and fossil excavation. He was a lifelong inventor, constantly seeking ways to improve daily life and technical processes. His inventions included improvements to fireplace designs for better heating efficiency, a portable steam bath for health purposes, and innovations in spectacle making.

One of his notable inventions was the polygraph, a device that could create duplicate copies of a letter as it was being written. This was not a copier in the modern sense, but a mechanical apparatus using linked pens. Peale refined existing designs and produced versions used by figures like Thomas Jefferson, who valued it greatly for managing his extensive correspondence. Peale also experimented with porcelain production for false teeth and developed new methods for preserving specimens through arsenic poisoning, which, while effective, posed health risks to those working with the materials, including himself and his family. His inventive spirit reflected the era's optimism about human ingenuity and progress.

A Patriarch of Art: The Peale Dynasty

Charles Willson Peale was not only a prolific artist himself but also the patriarch of America's first artistic dynasty. He believed strongly in nurturing talent and passed on his skills and enthusiasm to his children and other family members. He famously named many of his children after renowned European artists, signaling his aspirations for them: Raphaelle, Angelica Kauffman, Rembrandt, Titian Ramsay, Rubens, and Sophonisba Angusciola. Several of them, along with his brother James, became significant artists in their own right.

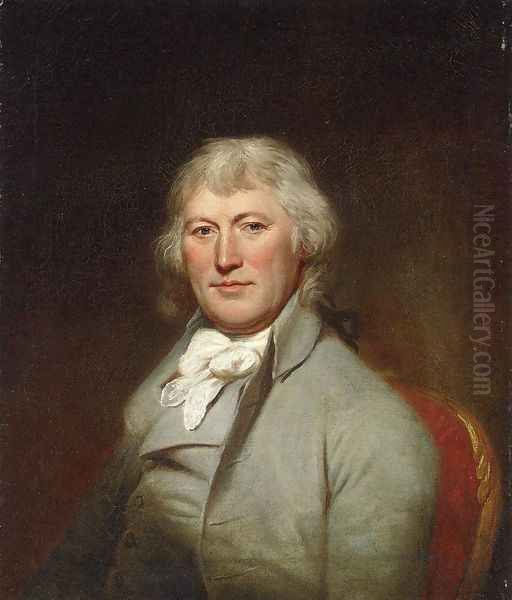

James Peale (1749-1831): Charles's younger brother, James, initially worked as a frame maker and assistant in Charles's studio. He developed into a talented artist, particularly noted for his miniature portraits and, later in life, for his still life paintings, which are considered among the finest produced in early America. He also painted landscapes and some historical scenes, establishing his own distinct artistic identity while remaining closely associated with his brother.

Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825): The eldest son, Raphaelle, is widely regarded today as America's first professional still life painter. His meticulously rendered compositions of food, tableware, and everyday objects are admired for their deceptive simplicity, subtle arrangements, and often melancholic undertones. Despite struggling with alcoholism and poor health (possibly exacerbated by arsenic and mercury used in his taxidermy work for the museum), Raphaelle created a body of work that stands as a high point in American still life painting.

Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860): Perhaps the most commercially successful of Peale's artist sons, Rembrandt achieved fame as a portraitist. He painted many prominent figures, including an iconic "porthole" portrait of George Washington based on his own life sitting in 1795, and a well-known portrait of Thomas Jefferson. Rembrandt traveled extensively, studied in Europe, and operated museums in Baltimore and Philadelphia. He was also involved in founding art institutions, such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (along with his father) and was a prominent figure in the New York art world. His style evolved over his long career, often showing a more Romantic sensibility than his father's work.

Rubens Peale (1784-1865): Named after the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, Rubens Peale spent much of his life managing the family museums in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York. He suffered from weak eyesight, which initially limited his artistic pursuits. However, late in life, after retiring from museum work, he took up still life painting with enthusiasm, creating charmingly detailed, if somewhat naive, depictions of fruits and flowers, often informed by his lifelong interest in horticulture.

Titian Ramsay Peale (1799-1885): The youngest son from Peale's first marriage, Titian Ramsay Peale (often referred to as Titian Peale II, to distinguish him from an elder brother who died young) combined artistic talent with a passion for natural history. He became a respected naturalist and scientific illustrator, participating in several major scientific expeditions, including Stephen H. Long's expedition to the Rocky Mountains (1819-1820) and, most notably, the United States Exploring Expedition (Wilkes Expedition) to the Pacific and Antarctica (1838-1842). His detailed drawings and watercolors of flora and fauna documented numerous species for science.

Female Artists in the Peale Family: Charles Willson Peale also encouraged the artistic talents of his daughters and nieces. His daughter Sophonisba Angusciola Peale Sellers (1786-1859), named after the Italian Renaissance painter, was known for her Quaker-themed paintings and still lifes. Another daughter, Angelica Kauffman Peale Robinson (1776-1853), named after the Swiss Neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman (a contemporary Peale admired), also painted, primarily miniatures and small portraits. More prominent were James Peale's daughters: Anna Claypoole Peale (1791-1878) became a successful and sought-after miniaturist, elected to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her sister, Sarah Miriam Peale (1800-1885), achieved even greater recognition as a professional portrait and still life painter, working successfully in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and later St. Louis. She is considered one of the leading female artists of her generation and was also elected an Academician at the Pennsylvania Academy.

The Peale family's collective artistic output significantly shaped the development of portraiture, still life, and scientific illustration in the United States for nearly a century. They operated as a collaborative enterprise, particularly in the running of the museum, where family members assisted with everything from taxidermy and frame making to greeting visitors and maintaining the collections.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Charles Willson Peale worked during a vibrant period for American art, despite the challenges of revolution and nation-building. His career overlapped with several other key figures. His relationship with Benjamin West (1738-1820) was foundational, providing him with crucial training and connections in London. West, as historical painter to King George III and later president of the Royal Academy, served as a mentor to a generation of American artists who studied abroad.

John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), though he emigrated permanently to England in 1774, set a high standard for realism and psychological depth in colonial portraiture that influenced Peale and others. Peale's directness and solid modeling can be seen as continuing a native tradition also evident in Copley's American work.

In the post-Revolutionary period, Peale's main rival in portraiture, particularly for prestigious commissions like presidential portraits, was Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828). Stuart, also trained in London (under West), developed a more fluid, painterly style, often focusing on capturing the sitter's essence with seemingly effortless brushwork, contrasting with Peale's more meticulous and linear approach. Their differing styles offer fascinating comparisons in depictions of figures like Washington.

Other notable contemporaries included John Trumbull (1756-1843), known for his ambitious historical paintings of the Revolution, particularly the series displayed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda; Mather Brown (1761-1831), another American who studied with West and found success painting portraits in London; and Joseph Wright (1756-1793), son of the wax sculptor Patience Wright, who also painted portraits of Washington and designed early U.S. coinage. Peale's engagement with these artists, whether through direct interaction, rivalry, or shared mentorship under West, places him firmly within the developing artistic community of the early republic.

Anecdotes and Character

Peale's life was filled with activities that reveal his energetic and sometimes eccentric character. His foray into wax figure making, mentioned in the provided text, aligns with the popular museum practices of the time, although wax was often seen as less prestigious than painting or sculpture. His museum's slogans, "School of Wisdom" and "Book of Nature," reflect his high-minded educational goals. However, the text also notes a potential misjudgment of public taste, suggesting that perhaps a greater emphasis on spectacle or the "exotic," common in other contemporary museums (like P.T. Barnum's later American Museum), might have ensured greater financial success.

His personal life had moments of drama. The mention of controversy surrounding his marriage to Mary Tilghman hints at social challenges he may have faced early on, though he ultimately achieved considerable respectability. His dedication is evident in his detailed diaries and letters, which provide invaluable insights into his activities, the Revolutionary period, his scientific inquiries, and his technical experiments, such as designs for seeding machines. The mastodon excavation, despite the failure of his initial drainage device, highlights his determination and willingness to undertake ambitious, hands-on projects.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

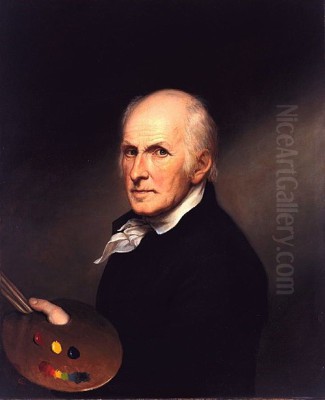

Charles Willson Peale remained active into his eighties, painting, inventing, and overseeing his various interests. His famous late self-portrait, The Artist in His Museum (1822), depicts him dramatically lifting a curtain to reveal the wonders of his natural history collection, symbolizing his life's work at the intersection of art and science. He undertook his final excavation attempt, seeking another mastodon, shortly before his death in 1827.

Peale's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he created an unparalleled visual record of the American Revolution's key figures, capturing their likenesses with honesty and skill. His works, particularly The Staircase Group and his portraits of Washington, remain staples of American art history. As a museum founder, he pioneered methods of display and established a model for public institutions dedicated to both natural history and art, emphasizing education and accessibility. His museum's collections eventually formed the basis for other institutions, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

As a scientist and inventor, he contributed to paleontology, taxidermy, and practical technology, embodying the spirit of inquiry and innovation of the Enlightenment. Finally, as a patriarch, he fostered a remarkable family dynasty that significantly enriched American art and science for generations. Charles Willson Peale was truly a Renaissance man of the early American Republic, whose energy and vision helped shape the cultural and intellectual landscape of the new nation.